Abstract

Objective

This paper advances current understanding of the contemporary crime drop by focusing on the changes in the age distribution of arrests from 1990 to 2010. Using the New York State Computerized Criminal History (CCH) file, which tracks every arrest in the state, we apply standard demographic methods to examine age-specific arrest rates over time. We test whether the 25 % drop in the felony arrest rate can be best explained by period or cohort effects with special attention to how the phenomenon varies across crime types and regions within the state.

Methods

Following the analytic approach of O’Brien and Stockard (J Quant Criminol 25(1):79–101, 2009), we fit the age–period–cohort (APC) model using the generalized inverse matrix, which creates an estimable model. We partition the model variation into each factor by subtracting the variation of the two-factor model from the variation of the three-factor model to provide a direct comparison of the two different classes of explanations for crime drop: period and cohort.

Results

Our analysis supports a cohort explanation over a period explanation. Controlling for the (substantial) variation due to age, the cohort effect accounts for twice as much of the remaining variation as the period effect. Specifically, the drop in arrest rates is concentrated in more recent birth cohorts across all ages. Although we found statistically significant age–period interaction effects for the younger age group (ages 16–20) in 1990 and 1995, the cohort effect was still a much stronger predictor of felony arrest rates than the period explanation, even with the age–period interaction.

Conclusions

The current study reports that the overall drop in felony arrest rates from 1990 to 2010 is mostly due to decreased arrests among those who were born after 1970 rather than a universal drop across different age groups. We discuss but do not test two potential explanations—the legalization of abortion and the ban on leaded gasoline—for the underlying factors associated with a different criminal propensity among birth cohorts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Index offense refers to eight crimes that the FBI reports in the annual Uniform Crime Report (UCR): Murder, forcible rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, larceny, and arson. These crime types are selected because they are serious offenses and most likely to be reported to the police. These crimes are now referred to as Type I offenses.

Demographers refer to changes that affect everyone in a given year equally, regardless of age, as period effects. Changes that affect only people from a given birth cohort regardless of age are referred to as cohort effects. Period effects may not be uniform across the entire sample. They may affect only people of a certain age (age–period interactions), or people from certain cohorts (cohort–period interactions).

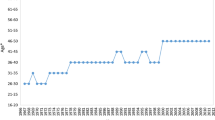

The share of the older age group (over age 40) in the total felony arrests increases over time: 9.3 % in 1990, 13.0 % in 1995, 18.3 % in 2000, 22.1 % in 2005, and 25.3 % in 2010. Given that the total volume of felony arrests consistently decreases over time, it addresses that the drop in the felony arrest for the younger age group is large enough to compensate the increase in the older age group.

The percent change in the counterfactual scenario is calculated based on assumption that the 2010 felony arrest counts for older age group has not changed since 1990: (Counterfactual arrest volume in 2010 − Actual arrest volume in 1990)/Actual Arrest volume in 1990 × 100 = (105,558–160,140)/160,140 × 100 = −34.1 %.

Appendix 2 shows the age groups by period and corresponding birth cohorts for our study sample.

The cohort effect has a larger number of degrees of freedom than the period effect, which increases the chances of finding statistically significant non-linear effects of period and cohort. Porter et al. (forthcoming) deal with a similar problem by replacing the cohort dummy variables with a more restricted polynomial functional form, essentially restricting the degrees of freedom for both cohort and period to be the same. Their main finding regarding the importance of cohort effects was unchanged, despite the fact that they had far more cohorts (n = 86) in their paper. Their result shows that additional degrees of freedom does not itself lead to the conclusion that cohort explanations are more powerful.

Utilizing the generalized inverse to get the estimates of the model is one of the estimable function approaches, such as the intrinsic estimator using the Moore–Penrose generalized inverse matrix. We address other types of the estimable function approach in conjunction with suggestions for future study in our discussion.

The results table and figure are not included in this paper but available upon request.

Although the coefficients in the age–period–cohort model are not estimable (and therefore not available for statistical testing), the coefficients in the two-factor (AP and AC) models are still estimable and available for hypothesis testing.

We also checked the graphs for the model including age*period interaction and confirmed that it does not do any better job than the age–period model.

The 17 IMPACT counties are: Albany, Broom, Chautauqua, Dutchess, Erie, Monroe, Nassau, Niagara, Oneida, Onondaga, Orange, Rensselaer, Rockland, Schenectady, Suffolk, Ulster, and Westchester; Project IMPACT has been replaced with operation Gun Involved Violence Elimination (GIVE), which remains focused the same 17 counties, but has evolved to focus specifically on gun violence.

Single-age population information at the county level is not available in the Census data. We used new age groups following the grouping of the Census for the APC analysis by region. The new age groups are as follows: 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, and 65–69 years.

The felony arrest rates in the rural upstate counties actually increased for the last 20 years. However, the magnitude of increase for the younger age group is much smaller than that for the older age group, which is in accordance with cohort explanation.

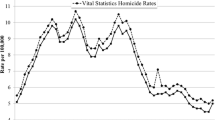

We explored the correlation between the number of index crimes reported to the police and the number of index arrests in a given year in New York State between 1990 and 2010. The correlation between the volume of index offenses reported to police and the volume of index arrests is very high (r = 0.931–0.960) across years.

References

Arnio AN, Baumer EP, Wolff KT (2012) The contemporary foreclosure crisis and US crime rates. Soc Sci Res 41(6):1598–1614. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.05.013

Baumer EP, Wolff KT (2014) Evaluating contemporary crime drop(s) in America, New York City, and many other places. Justice Q 31(1):5–38. doi:10.1080/07418825.2012.742127

Dietrich KN, Douglas RM, Succop PA, Berger OG, Bornschein RL (2001) Early exposure to lead and juvenile delinquency. Neurotoxicol Teratol 23(6):511–518. doi:10.1016/S0892-0362(01)00184-2

Donohue JJ III, Levitt SD (2001) The impact of legalized abortion on crime. Q J Econ 116(2):379–420. doi:10.2307/2696468

Donohue JJ III, Levitt SD (2004) Further evidence that legalized abortion lowered crime: a reply to Joyce. J Hum Resour 39(1):29–49. doi:10.2307/3559004

Easterlin RA (1978) What will 1984 be like? Socioeconomic implications of recent twists in age structure. Demography 15(4):397–432. doi:10.2307/2061197

Easterlin RA (1987) The new age structure of poverty in America: permanent or transient? Popul Dev Rev 13(2):195–208

Farrington DP (1986) Age and crime. Crime Justice 7:189–250. doi:10.2307/1147518

Fu WJ (2000) Ridge estimator in singulah oesiun with application to age–period–cohort analysis of disease rates. Commun Stat Theory Methods 29(2):263–278

Gottfredson M, Hirschi T (1990) A General theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Greene JA (1999) Zero tolerance: a case study of police policies and practices in New York City. Crime Delinq 45(2):171–187. doi:10.1177/0011128799045002001

Hirschi T, Gottfredson M (1983) Age and the explanation of crime. Am J Sociol 89(3):552–584. doi:10.1086/227905

Levitt SD (1997) Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effect of police on crime. Am Econ Rev 87(3):270–290

Levitt SD (2004) Understanding why crime fell in the 1990s: four factors that explain the decline and six that do not. J Econ Perspect 18(1):163–190. doi:10.1257/089533004773563485

Lott JR, Whitley J (2007) Abortion and crime: unwanted children and out-of-wedlock births. Econ Inq 45(2):304–324. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.2006.00040.x

Marvell TB, Moody CEJ (1994) Prison population growth and crime reduction. J Quant Criminol 10(2):109–140. doi:10.1007/BF02221155

Moffitt T, Silva P (1988) Self-reported delinquency, neuropsychological deficit, and history of attention deficit disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol 16(5):553–569. doi:10.1007/BF00914266

Needleman HL (2000) The removal of lead from gasoline: historical and personal reflections. Environ Res 84(1):20–35. doi:10.1006/enrs.2000.4069

Needleman HL, Riess JA, Tobin MJ, Biesecker GE, Greenhouse JB (1996) Bone lead levels and delinquent behavior. JAMA 275(5):363–369. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03530290033034

Nevin R (2000) How lead exposure relates to temporal changes in IQ, violent crime, and unwed pregnancy. Environ Res 83(1):1–22. doi:10.1006/enrs.1999.4045

NYSDCJS (2011) Crime in New York State 2011 final data. http://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/pio/annualreport/nys-crime-report-2010.pdf

NYSDCJS (2014) Crime in New York State 2013 final data. http://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/crimnet/ojsa/indexcrimes/nys-crime-report-2013.pdf

O’Brien RM (2000) Age period cohort characteristic models. Soc Sci Res 29(1):123–139. doi:10.1006/ssre.1999.0656

O’Brien RM (2014a) Estimable functions in age–period–cohort models: a unified approach. Qual Quant 48(1):457–474

O’Brien RM (2014b) Age–period–cohort models: approaches and analyses with aggregate data. Chapman and Hall/CRC, Boca Raton

O’Brien RM, Stockard J (2009) Can cohort replacement explain changes in the relationship between age and homicide offending? J Quant Criminol 25(1):79–101. doi:10.1007/s10940-008-9059-1

Pampel FC, Peters HE (1995) The Easterlin effect. Ann Rev Sociol 21:163–194. doi:10.2307/2083408

Porter LC, Bushway SD, Tsao HS, Smith HL (forthcoming). How the U.S. prison boom has changed the age distribution of the prison population. Criminology

Reyes J (2007) Environmental policy as social policy? The impact of childhood lead exposure on crime. BE J Econ Anal Policy. doi:10.2202/1935-1682.1796

Rodgers WL (1982) Estimable functions of age, period, and cohort Effects. Am Sociol Rev 47(6):774–787

Rosenfeld R, Fornango R (2014) The impact of police stops on precinct robbery and burglary rates in New York City, 2003–2010. Justice Q 31(1):96–122. doi:10.1080/07418825.2012.712152

Rosenfeld R, Messner SF (2009) The crime drop in comparative perspective: the impact of the economy and imprisonment on American and European burglary rates. Br J Sociol 60(3):445–471. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01251.x

Rosenfeld R, Oliver BE (2008) Evaluating recent changes in homicide and robbery rates. Justice Res Policy 10(2):49–65

Rosenfeld R, Fornango R, Rengifo AF (2007) The impact of order-maintenance policing on New York City homicide and robbery rates: 1988–2001. Criminology 45(2):355–384. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00081.x

Scheffé H (1959) The analysis of variance. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York

Searle SR (1971) Linear models. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York

Snyder HN (2012) Arrest in the United States, 1980–2009. (Report No. NCJ 234319). Retrieved from Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus8009.pdf

Steffensmeier D, Harer MD (1999) Making sense of recent U.S. crime trends, to 1996/1998: age composition effects and other explanations. J Res Crime Delinq 36(3):235–274. doi:10.1177/0022427899036003001

Steffensmeier DJ, Allan EA, Harer MD, Streifel C (1989) Age and the distribution of crime. Am J Sociol 94(4):803–831. doi:10.1086/229069

Stretesky PB, Lynch MJ (2001) The relationship between lead exposure and homicide. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 155(5):579–582. doi:10.1001/archpedi.155.5.579

Tarone RE, Chu KC (1996) Evaluation of birth cohort patterns in population disease rates. Am J Epidemiol 143(1):85–91

U.S. Census Bureau (2011) State population estimates, 1990–2010. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/historical/index.html

United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation (2011) Crime in the United States, 1990–2010. Prepared by the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data. http://www.ucrdatatool.gov

Weisburd D, Telep CW, Lawton BA (2014) Could innovations in policing have contributed to the New York City crime drop even in a period of declining police strength?: The case of stop, question and frisk as a hot spots policing strategy. Justice Q 31(1):129–153. doi:10.1080/07418825.2012.754920

Yang Y, Fu WJ, Land KC (2004) A methodological comparison of age–period–cohort models: the intrinsic estimator and conventional generalized linear models. Sociol Methodol 34(1):75–110

Yang Y, Schulhofer-Wohl S, Fu WJ, Land KC (2008) The intrinsic estimator for age–period–cohort analysis: what it is and how to use it1. Am J Sociol 113(6):1697–1736

Zimring FE (2007) The Great American crime decline. Oxford University Press, New York

Zimring FE (2011) The city that become safe: New York’s lessons for urban crime and its control. Oxford University Press, New York

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the feedback from the National Academy of Sciences Roundtable on Crime Trends. In particular, we wish to thank Richard Rosenfeld and Malay Majmundar for support and encouragement. We also wish to think the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, which provided access to the Computerized Criminal History File. Finally, the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis of the University at Albany provided technical and administrative support for this research through a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24-HD044943).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclaimer This data is provided by the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not those of DCJS. Neither New York State nor DCJS assumes liability for its contents or use thereof.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Bushway, S. & Tsao, HS. Identifying Classes of Explanations for Crime Drop: Period and Cohort Effects for New York State. J Quant Criminol 32, 357–375 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9274-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9274-5