Abstract

This paper compares the working hours and life satisfaction of Americans and Europeans using the World Values Survey, Eurobarometer and General Social Survey. The purpose is to explore the relationship between working hours and happiness in Europe and America. Previous research on the topic does not test the premise that working more makes Americans happier than Europeans. The findings suggest that Americans may be happier working more because they believe more than Europeans do that hard work is associated with success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that happiness means general life satisfaction or happiness, not job satisfaction. The focus here is on the life satisfaction literature and modeling.

The goal of this paper is to document a relationship between working hours and happiness in the US and Europe. A more theoretical account has been provided elsewhere, see Alesina et al. (2005) for instance.

Life satisfaction and happiness are conceptually different. The former refers to cognition while the latter refers to affect. For simplicity I use them interchangeably and specifically I mean life satisfaction.

Choice of these years is determined by data availability for Europe, so that Europeans and Americans were surveyed approximately at the same time.

Still, robustness of the results can be improved if wording of the survey questions is the same for all respondents. This remains for the future research when better data become available.

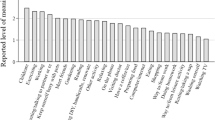

For a list of European countries and American regions see Appendix 1. There is a statistically and substantively significant variation across European countries in average happiness, but country-level analysis is difficult due to small sample sizes.

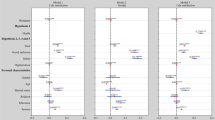

These models may suffer from left out variable bias, however. Additional controls are used in separate models for the US and Europe. Results are shown in Appendix 3. The relationship is robust: in all models Europeans are less happy than Americans when working longer hours.

Figure 2 utilizes postgr3 by Michael Mitchell and spostado by Scott Long in Stata .

This is a hypothetical scenario. Again, as argued in this paper, for Europeans it makes sense to work less and for Americans to work more.

However, this relationship is not necessarily causal for two main reasons. Data is cross-sectional, and it is not entirely clear what is the direction of causality here, although it seems more reasonable that working more makes Americans happier than that happier Americans work more than Europeans. If the reader has ideas about enhancing causal inference, please email me.

For ease of exposition variables were recoded so that higher value means that work is more important. Responses to these questions were standardized so that they are comparable in Fig. 3.

Again, there is a need for more research on this: There may be other plausible explanations.

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Alesina, A., Glaeser, E. L., & Sacerdote B. (2005). Work and leisure in the U.S. and Europe: Why so different? Working Paper 11278, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Benahold, K. (2004, July 29). Love of leisure and Europe’s reasons. The New York Times.

Clark, A. E., & Senik, C. (2006). The (unexpected) structure of rents on the French and British labour markets. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 180–196.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., & Lucas R. E. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 98–125), New York: Academic Press, Inc.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 27, 35–47.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Economic Journal, 111, 465–484.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 11176–11183.

Easterlin, R. A. (2005). Building a better theory of well-being. In L. Bruni & P. L. Porta (Eds.), Economics and happiness. Framing the analysis (pp. 29–65). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ferguson, N. (2003, June 8). Why America outpaces Europe (Clue: The God Factor). The New York Times.

Frijters, P., & Leigh, A. (2008). Materialism on the March: From conspicuous leisure to conspicuous consumption? Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 1937–1945.

Golden, L., & Wiens-Tuers B. (2006). To your happiness? Extra hours of labor supply and worker well-being). The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 382–397.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables, SAGE Publications, 2nd ed.

Michelacci, C., & Pijoan-Mas J. (2007a). The effects of labor market conditions on working time: The US-EU experience. CEPR Discussion Paper, 6314.

Michelacci, C. (2007b). Why do Americans work more than Europeans? Differences in Career Prospects. CEPR Policy Insight, 12.

Myers, D. G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55, 56–67.

Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy? Psychological Science, 6, 10–19.

Oswald, A. J. (1997). Happiness and economic performance. Economic Journal, 107, 1815–1831.

Prescott, E. C. (2004). Why do Americans work so much more than Europeans? Federal Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 28, 2–13.

Putnam, R. D. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Sanfey, P., & Teksoz, U. (2005). Does transition make you happy? EBRD Working Paper 58.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers J. (2009). The paradox of declining female happiness. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1, 190–225.

Weber, M., Parsons, T., & Tawney, R. H. (2003). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Dover Value Editions). Mineola: Dover Publications.

Wharton. (2006). Reluctant vacationers: Why Americans work more, relax less, than Europeans. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=1528.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Adam Okulicz-Kozaryn is indebted to Micah Altman and Ben Gaddis.

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Figs. 4 and 5, Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Appendix 2

See Tables 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 22

Appendix 3

See Tables 23, 24, 25, 26 and 27.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. Europeans Work to Live and Americans Live to Work (Who is Happy to Work More: Americans or Europeans?). J Happiness Stud 12, 225–243 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9188-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9188-8