Abstract

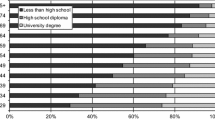

The transitional decline of fertility in Italy has never been studied using micro-data, with the exception of small areas. For the first time, we use individual retrospective fertility data collected for all the ever married women living in 20 % of households subjected to census in 1971 in the Veneto region (North-East Italy), a ‘late-comer’ area in the context of Western European fertility decline (TFR = 5.0 in 1871 and 1921, 2.5 in 1951 and 1971). In order to consider broad explanations of fertility decline, we combine individual retrospective data with other information available at two territorial levels (58 districts and 582 municipalities), using a three-level clustered regression model (district, municipality, woman). The main results are: (1) even if the (few) women with 8 + years of schooling born in the last decades of the nineteenth century already had a TFR around two, this value is not seen among women with low levels of education until those born 50 years later; (2) the link between fertility and secularization strengthens cohort after cohort, whereas the connections between fertility and industrialization and fertility and urbanization weaken; (3) throughout the period, the statistical inverse relationship between education and fertility is strong, both at the territorial and individual level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As written in all his biographies to underline his ‘tenacity’, Giuseppe Sarto (the future Pope Pius X, who was the second of ten children of a poor farmer), during the school year 1846–47, when he was 11-year-old, walked 7 + 7 km per day, from his village of Riese to the town of Castelfranco Veneto (in the province of Treviso), to attend the 5th grade. The same happened 90 years later, in the school year 1934–35 to the mother of one of the authors of this article, although the path was shorter (3 + 3 km), between the villages of Santa Giustina in Colle and Fratte (in the province of Padua).

One peculiarity that must be taken into account for its possible effects on reproductive behavior is the clash between the Catholic Church and State that has characterized Veneto—as for Italy as a whole—at the turn of the 1900 (Spadolini and Ceccuti 1980). This was a consequence of the fact that the unification of Italy was obtained in 1861–1870 against the will of the Holy See. The fracture was recomposed only in 1929 with ‘Patti Lateranesi’ between Pius XI and Mussolini, but because of this historical contingency—in contrast to what happened in other strongly religious regions—for fifty years the Catholic Church was kept out of some public organizations, mainly the primary and secondary schools and universities. This fact may have accentuated the connection between the diffusion of education and the decline of fertility.

The data of the retrospective fertility survey included in the 1971 census sheet are currently available only for the Veneto region. In 1971 Istat (Italian national statistics institute) stored on magnetic tapes individual census data for the whole Italian population covering only basic characteristics (as sex, birth date, marital status, education, etc.). Those characteristics that were considered less relevant (as daily mobility, migration, and women fertility – see Istat 1977a, b, p. VII-IX) were recorded only for one household out of five (thus, a systematic sample of 20 % of households; for further details on sampling see Istat 1977a, p. 109–111, 116–118, 128). For unknown reasons, the results of the analyses on female fertility were never published by Istat. The magnetic tapes where this 20 % sample was stored at certain point were no more readable (they demagnetized inadvertently). As far as we know, only data for Veneto were recovered because an extra copy of them was stored at the Department of Statistics of Padua University for research purposes.

However, the first results of a research by Caselli et al. (2013), that compared the survival of a sample of centenarians born between 1890 and 1904 in the Italian region of Sardinia with women of the same cohorts who died at ages 60–79, show that in this population the survival after age 80 is not related to the number of children but only to the age at last birth.

The exact number of net emigrants from Veneto is unknown. Between 1876 and 1925 3.6 millions of residents left the region, that at the time included also Friuli province (CGE 1926). 20 % of them were women, a quote increasing up to 30 % after World War Two (Istat 1965). The net migratory rate for Veneto and Friuli was −8.5 ‰ between 1881 and 1901 and −6.4 ‰ between 1901 and 1911 (Birindelli 2004).

In this paper, we consider only the possibility of territorial clusters. In fact, this reasoning can be extended to all social groups to which a woman/couple is a part, as proposed by Kravdal (2012).

We use the median number of children instead of the absolute number of children because we think that the median is more appropriate to verify if a deviation from social norms corresponds to a deviation in the reproductive behavior (a number of children lower or higher than the median for that cohort). However, our key results do not change much if using the absolute number of children as the response variable: structural changes remain the most relevant determinants of reproductive changes in older cohorts, secularization in the younger ones, while the spreading of education remains important for all the cohorts (results available on demand).

In our models we tested an index of the presence of malaria for the oldest cohorts, but it never resulted in statistical significance: this disease was indeed correlated to the environmental characteristics of each area (presence of swamps and marshes), but not to poverty/fertility.

References

Allum, P. (1997). “From two into one”: The faces of the Italian Christian Democratic party. Party Politics, 3, 23–25.

Anastasia, B., & Rullani, E. (1982). La nuova periferia industriale. Venezia: Arsenale Editrice.

Anderson, M. (1998). Highly restricted fertility: Very small families in the British fertility decline. Population Studies, 52, 177–199.

Angels, G., Guilkey, D., & Mroz, T. (2005). The impact of community-level variables on individual-level outcomes. Theoretical results and applications. Sociological Methods Research, 34, 76–121.

Bagnasco, A. (1984). Tre Italie. La problematica territoriale dello sviluppo italiano. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Bagnasco, A., & Trigilia, C. (Eds.). (1984). Società e politica nelle aree di piccola impresa. Il caso di Bassano. Venezia: Arsenale Editrice.

Basu, A. M. (2002). Why education leads to lower fertility? A critical review of some of the possibilities. World Development, 30, 1779–1790.

Becker, G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 279–288.

Becker, G. (1992). Fertility and the economy. Journal of Population Economics, 5, 185–201.

Birindelli, A. M. (2004). Migrazioni. In G. Dalla-Zuanna, A. Rosina, F. Rossi (Eds.), Il Veneto. Storia della popolazione dalla caduta di Venezia a oggi (pp. 227–248). Venezia: Marsilio.

Bongaarts, J., & Watkins, S. (1996). Social interactions and contemporary fertility transitions. Population and Development Review, 22, 639–682.

Breschi, M., Derosas, R., Manfredini, M., & Rettaroli, R. (2010). Patterns of reproductive behavior in preindustrial Italy. Casalguidi, 1819 to 1859, and Venice, 1850 to 1869. In N. O. Tysuia, W. Feng, G. Alter, J. Z. Lee (Eds.), Prudence and pressure. Reproduction and human agency in Europe and Asia, 1700–1900 (pp. 217–248). Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Breschi, M., Esposito, M., Mazzoni, S., & Pozzi, L. (2014a). Fertility transition and social stratification in the town of Alghero, Sardinia (1866–1935). Demographic Research, 30, 823–852.

Breschi, M., Fornasin, A., & Manfredini, M. (2013). Patterns of reproductive behavior in transitional Italy: The rediscovery of the Italian fertility survey of 1961. Demographic Research, 29, 1227–1260.

Breschi, M., Fornasin, A., Manfredini, M., Pozzi, L., Rettaroli, R., & Scalone, F. (2014b). Social and economic determinants of reproductive behavior before the fertility decline. The case of six Italian communities during the nineteenth century. European Journal of Population, 30, 291–315.

Breschi, M., Manfredini, M., Mazzoni, S., & Pozzi, L. (2009). Fertility and socio-cultural determinants at the beginning of demographic transition. Sardinia, 19th and 20th centuries. In A. Fornasin & M. Manfredini (Eds.), Fertility in Italy at the turn of the twentieth century (pp. 63–78). Udine: Forum.

Caldwell, J. C. (1980). Mass education as a determinant of the timing of fertility decline. Population and Development Review, 6, 225–255.

Caldwell, J. C. (1982). Theory of fertility decline. London: Academic Press.

Caltabiano, M. (2008). Has the fertility decline come to an end in the different regions of Italy? New insights from a cohort approach. Population, 63, 151–171.

Caselli, G., Lipsi, R. M., Lapucci, E., & Vaupel, J. W. (2013). Exploring Sardinian longevity and its association with reproductive behaviors and infant mortality. Paper presented at the 2013 Population Association of America Annual Meeting, New Orleans, April 11-13. http://paa2013.princeton.edu/papers/130704.

Casterline, J. B. (Ed.). (1985). The collection and analysis of community data. Voorburg: International Statistics Institute.

Castiglioni, M., & Dalla-Zuanna, G. (1988). Variazioni nel livello di istruzione e nel comportamento fecondo: un’analisi empirica. Proceedings of the XXXIV Scientific Meeting of the Italian Statistical Society (Vol. 3, pp. 89–92). SIS: Siena.

Castiglioni, M., & Dalla-Zuanna, G. (2009). Marital and reproductive behavior in Italy after 1995: Bridging the gap with Western Europe. European Journal of Population, 25, 1–26.

Castiglioni, M., & Vitali, A. (2013). The geography of secularization and reproductive behaviour. Continuity and change in a Catholic setting (North Eastern Italy, 1946–2008). Paper presented at the 10th Giornate di Studio sulla Popolazione, Brixen (Italy), Feb 6–8. http://www.sis-aisp.it/ocs-2.3.4/index.php/gsp2013/gsp2013.

CGE – Commissariato Generale dell’Emigrazione. (1926). Annuario statistico dell’emigrazione italiana dal 1876 al 1925. Roma: Commissariato Generale dell’Emigrazione.

Coale, A. (1973). The demographic transition. In Proceedings of International Population Conference (pp. 53–72). Liege: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population

Coale, A., & Watkins, S. (Eds.). (1986). The decline of fertility in Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dalla-Zuanna, G. (1990). Aspetti demografici della fecondità nel Veneto fra 1866 e 1986. Technical Reports Series no. 1. Padova: Department of Statistics.

Dalla-Zuanna, G. (1997). Differenze socio-economiche e fecondità nei distretti del Veneto. Sides (Italian Society of Historical Demography), Disuguaglianze: stratificazione e mobilità sociale nelle popolazioni italiane (Vol. 1, pp. 311–340). Clueb: Bologna.

Dalla-Zuanna, G. (2000). The banquet of Aeolus. A familistic interpretation of Italy’s lowest low fertility. Demographic Research, 4, 133–162.

Dalla-Zuanna, G. (2004). Sopravvivenza dei giovani e degli adulti. In G. Dalla-Zuanna, A. Rosina, F. Rossi (Eds.), Il Veneto. Storia della popolazione dalla caduta di Venezia a oggi (pp. 195–226). Venezia: Marsilio.

Dalla-Zuanna, G. (2010). Bassa fecondità e nuova mentalità. Padova: Cleup.

Dalla-Zuanna, G. (2011). Tacit consent: The church and birth control in Northern Italy. Population and Development Review, 37, 361–374.

Dalla-Zuanna, G., Rosina, A., & Rossi, F. (Eds.). (2004). Il Veneto. Storia della popolazione dalla caduta di Venezia a oggi. Venezia: Marsilio.

De Sandre, P. (1971). Recherche par micro-zones sur les relations entre fécondité et certaines caractéristiques du milieu économique et social dans une région italienne. Genus, XXVII, 1–28.

Derosas, R. (2003). Watch out for the children! Differential infant mortality of Jews and Catholics in nineteenth-century Venice. Historical Methods, 36, 109–130.

Doblhammer, G. (2000). Reproductive history and mortality later in life: A comparative study of England and Wales and Austria. Population Studies, 54, 169–176.

Doblhammer, G., & Oeppen, J. (2003). Reproduction and longevity among the British peerage: The effect of frailty and health selection. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London/B, 270(1524), 1541–1547.

Dribe, M., Oris, M., & Pozzi, L. (2014). Socioeconomic status and fertility before, during, and after the demographic transition: An introduction. Demographic Research, 31, 161–182.

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12, 121–138.

Entwisle, B., Mason, W., & Hermalin, A. (1986). The multilevel dependence of contraceptive use on socioeconomic development and family planning program strength. Demography, 23, 199–216.

Festy, P. (1984). La fécondité des pays occidentaux de 1870 à 1970. Paris: INED–PUF.

Filippini, N., & Plebani, T. (1999). La scoperta dell’infanzia. Cura, educazione e rappresentazione. Venezia 1750–1930. Venezia: Marsilio.

Forcucci, L. (2010). Battle for births: The fascist pronatalist campaign in Italy 1925 to 1938. Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Europe, 10, 4–13.

Forti-Messina, A. L. (1984). I medici condotti e la professione del medico nell’ottocento. Società e Storia, 23, 101–161.

Fuà, G., & Zacchia, C. (Eds.). (1983). Industrializzazione senza fratture. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Fumian, C., & Ventura, A. (2004). Storia del Veneto. Vol. 2. Dal Seicento a oggi. Bari: Laterza.

Gambasin, A. (1978). Parroci e contadini nel Veneto alla fine dell’Ottocento. Vicenza: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura.

Greenhalgh, S. (1988). Fertility as mobility: Sinic transitions. Population and Development Review, 14, 629–674.

Ipsen, C. (1996). Dictating demography: the problem of population in fascist Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Istat (1936). Indagine sulla fecondità della donna. Censimento del 1931, vol. VI. Roma: Istituto Centrale di Statistica.

Istat (1965). Sviluppo della popolazione italiana dal 1861 al 1961. Annali di Statistica, Serie VIII, vol. 17. Roma: Istituto Centrale di Statistica.

Istat (1974). Indagine sulla fecondità della donna. Note e relazioni, 50. Roma: I-sta-t.

Istat (1977a). 11° Censimento Generale della Popolazione. Volume XI. Atti del censimento. Roma: Istat.

Istat (1977b). 11° Censimento Generale della Popolazione. Volume IX. Risultati degli spogli campionari. Tomo 1. Roma: Istat

Jaffe, A. (1942). Urbanization and fertility. American Journal of Sociology, 48, 48–60.

Kohler, H.-P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28, 641–680.

Kravdal, O. (2012). Further evidence of community education effects on fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Demographic Research, 27(645), 680.

Kravdal, O., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2008). Changing relationships between education and fertility: A study of women and men born 1940 to 1964. American Sociological Review, 73, 854–873.

Lanaro, S. (Ed.). (1984). Storia d’Italia. Il Veneto. Torino: Einaudi.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Lopez-Gay, A. (2013). Spatial continuities and discontinuities in two successive demographic transitions: Spain and Belgium, 1880–2010. Demographic Research, 28, 77–136.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Wilson, C. (1986). Modes of production, secularization and the pace of the fertility decline in western Europe, 1870–1930. In A. J. Coale & S. C. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe (pp. 261–292). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Livi-Bacci, M. (1977). A history of Italian fertility during the last two centuries. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Livi-Bacci, M. (1986). Fertility, nutrition and pellagra: Italy during the vital revolution. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 16(3), 431–454.

Mainardi, R. (2005). Il Veneto contemporaneo: un caso di modernizzazione tardiva. In A. Ferrari-Bravo (Ed.), Il Veneto, guida d’Italia del Touring Club Italiano (pp. 60–62). Milano: Touring Editore.

Manfredini, M., & Breschi, M. (2008). Socioeconomic structure and differential fertility by wealth in a mid-nineteenth century Tuscan community. Annales de Demographie Historique, 115, 15–33.

Mason, K. (1997). Explaining fertility transitions. Demography, 34, 443–454.

McQuillan, K. (2004). When does religion influence fertility? Population and Development Review, 30, 25–56.

Michielin, F. (2004). Lowest low fertility in an urban context: The role of migration in Turin, Italy. Population, Space and Place, 10, 331–347.

Nava, P. (Ed.) (1992). Operaie, serve, maestre, impiegate. Proceedings of the International Conference: Il lavoro delle donne nell’Italia contemporanea: continuità e rottura, Carpi, 6–8 April 1990. Torino: Rosemberg & Sellier.

Paccagnella, O. (2006). Centering or not centering in multilevel models? The role of the group mean and the assessment of group effects. Evaluation Review, 30, 66–85.

Pizzetti, P., Fornasin, A., & Manfredini, M. (2012). La fecondità nell’Italia nord-orientale durante il fascismo: un’applicazione del metodo dei figli propri al censimento del 1936. Istat e Sides (Italian Society of Historical Demography), I censimenti nell’Italia unita (pp. 199–215). Istat: Roma.

Reher, D. S. (1998). Family ties in Western Europe: persistent contrasts. Population and Development Review, 24, 203–234.

Rettaroli, R., & Scalone, F. (2012). Reproductive behavior during the pre-transitional period: Evidence from rural Bologna. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 42, 615–643.

Rosina, A., Testa, M. R., & Pretato, A. (2000). Non solo emigrazioni: strategie di risposta alla crisi di fine ‘800 nel Veneto. Popolazione e Storia, 1, 97–122.

Rosina, A., & Zannini, A. (2004). Mortalità infantile. In G. Dalla-Zuanna, A. Rosina, F. Rossi (Eds.), Il Veneto. Storia della popolazione dalla caduta di Venezia a oggi (pp. 177–194). Venezia: Marsilio.

Rossi, F., & Meggiolaro, S. (2006). Da nord est a nord ovest. Gli emigrati veneti in Italia nel XX secolo. Padova: Cleup.

Rowland, D. T. (2007). Historical trends in childlessness. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 1311–1337.

Salvini, S. (1990). Caratteristiche del declino della fecondità europea nel corso dei secoli XIX e XX. Alcune considerazioni sulla transizione demografica in Italia. In SIDES (Italian Society of Historical Demography), Popolazione, società, ambiente: Temi di demografia storica italiana (secc. XVII-XIX) (pp. 385-402). Bologna: Clueb.

Santini, A. (1974). La fecondità delle coorti: studio longitudinale della fecondità italiana dall’inizio del secolo XX. Firenze: Dipartimento statistico matematico dell’Università di Firenze.

Santini, A. (1997). La fecondità nelle regioni italiane, analisi per coorti: anni 1952–1993. Collana Informazioni, n. 35. Roma: Istat.

Scalone, F., Rettaroli, R., Samoggia, A., & Petracci, E. (2013). The fertility transition in the area of Bologna: An analysis based on longitudinal data. The case of Granarolo from 1900 to 1940. Paper presented at the XXVII IUSSP International Conference, Busan, South Korea, Aug 26–31.http://www.iussp.org/en/event/17/programme/paper/3504

Shorter, E., Knodel, J., & Van De Walle, E. (1971). The decline of non marital fertility in Europe, 1880-1940. Population Studies, 25, 375–393.

Skirbekk, V. (2008). Fertility trends by social status. Demographic Research, 18, 145–180.

Spadolini, G., & Ceccuti, C. (1980). Chiesa e Stato dal Risorgimento alla Repubblica. Firenze: Le Monnier.

Toulemon, L. (1995). Très peu de couples restent volontairement sans enfant. Population, 50, 1079–1109.

Treves, A. (2002). Le nascite e la politica nell’Italia del Novecento. Milano: LED.

United Nations. (1994). Population, urbanization and quality of life. New York: United Nations Centre for Human Settlements.

Van Bavel, J. (2014). The mid-twentieth century Baby Boom and the changing educational gradient in Belgian cohort fertility. Demographic Research, 30, 925–962.

Van Bavel, J., & Reher, D. S. (2013). The Baby Boom and its causes: What we know and what we need to know. Population and Development Review, 39, 257–288.

Vitali, O. (1983). L’evoluzione rurale-urbana in Italia. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anna De Angelini and Fiorenzo Rossi for their help in decoding 1971 census data and the participants of the 2012 EAPS conference in Stockholm and the 2013 IUSSP conference in Busan for their useful comments. The research of this article was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Education (PRIN 2009 Program).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caltabiano, M., Dalla-Zuanna, G. The Delayed Fertility Transition in North-East Italy. Eur J Population 31, 21–49 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-014-9328-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-014-9328-7