Summary

Objective

The study aimed to assess the subjectively perceived need for additional general disease-oriented and psychotherapeutic care in patients with suspected cardiac disease and to investigate if the request for additional care is consistent with impairment of generic quality of life and the presence of psychosomatic risk factors.

Material and methods

Patients referred for cardiac stress testing because of suspected cardiac disease completed the assessment of the demand for additional psychological treatment (ADAPT) questionnaire, an assessment tool for counselling demand in patients with chronic illness, the SF-36 quality of life and the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) questionnaires.

Results

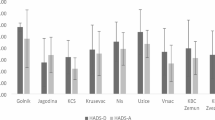

The questionnaires were administered to 233 patients (age: 54.5 ± 13.4, 57.5 % male). Exclusive demand for disease-oriented counselling was indicated by 45.1 %, demand for psychotherapeutic counselling (exclusive or combined with disease-oriented demand) by 33.9 %. Almost all patients with psychotherapeutic demand (96.3 %) expressed also request for disease-oriented counselling. Patients with exclusive demand for disease-oriented counselling showed significantly lower scores in the emotional and physical functioning and role domains of the SF-36 than the norm population. Patients demanding psychotherapeutic counselling reported significantly lower scores in all SF-36 domains than the norm population. Psychotherapeutic demand was strongly associated with positive indicators for mental distress: SF-36 MH (OR: 4.1), SF-36 MCS (OR: 5.9), HADS anxiety (OR: 3.9), and HADS depression (OR: 3.0).

Conclusions

Our study shows that the patients’ request for additional care reflects impairment of generic health status and psychological risk load. This indicates that the assessment of subjectively perceived demand allows to screen for patients who are in need of psychosomatic care and motivated to participate in additional counselling and therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- ADAPT:

-

Assessment of the demand for additional psychological treatment questionnaire

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- SF-36:

-

Short form 36 generic health questionnaire

- PCS:

-

Physical component summary of the SF-36

- MCS:

-

Mental component summary of the SF-36

- MH:

-

Mental health domain of the SF-36

- HADS:

-

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

References

Strike P, Steptoe A. Psychosocial factors in the development of coronary artery disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;46(4):337–47.

Kuper H, Marmot M, Hemingway H. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies of psychosocial factors in the etiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Semin Vasc Med. 2002;2(3):267–314.

Neylon A, Canniffe C, Anand S, et al. A global perspective on psychosocial risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55(6):574–81.

Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary: Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(19):2375–414.

Lichtman JH, Bigger JT, Blumenthal JA, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: Endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118(17):1768–75.

Ladwig K‑H, Lederbogen F, Albus C, et al. Positionspapier zur Bedeutung psychosozialer Faktoren in der Kardiologie. Kardiologe. 2013;7(1):7–27.

Engel G. The Need for a new medical model: A Challenge to Biomedicine. Science (80- ). 1977;196(4286):129–36.

Adler RH. Engel’s biopsychosocial model is still relevant today. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(6):607–11.

Fava GA, Sonino N. Psychosomatic medicine. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(8):1155–61.

Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, Saab PG, Kubzansky L. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: the emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(5):637–51.

Titscher G, Schöppl C, Gaul G. Aufgaben und Möglichkeiten integrierter psychokardiologischer Versorgung. J Kardiol. 2010;17:36–42.

Titscher G. Psychosomatische Konsiliar-Liaison-Dienste in der Kardiologie. In: Hermann-Lingen Ch, Albus Ch, Titscher G, editors. Psychokardiologie. Köln: Deutscher Ärzte Verlag; 2014. pp. 249–60.

Schneider W, Basler H, Beisenherz B. Fragebogen zur Messung der Psychotherapiemotivation. Weinheim: Beltz; 1990.

Schneider W, Klauer T. Symptom level, treatment motivation, and the effects of inpatient psychotherapy. Psychother Res. 2001;11(2):153–67.

Schneider W, Klauer T, Janssen P, Tetzlaff M. Zum Einfluß der Psychotherapiemotivation auf den Psychotherapieverlauf. Nervenarzt. 1999;70:240–9.

Nickel C, Tritt K, Kettler C, et al. Motivation for therapy and the results of inpatient treatment of patients with a generalized anxiety disorder: A prospective study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117(9–10):359–63.

Miehsler W. Assessing the demand for psychological care in chronic diseases. Developement and validation of a questionnaire based on the example of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10(5):9–11.

Miehsler W, Dejaco C, Moser G. Factor analysis of ADAPT questionnaire for assessment of subjective need for psychological interventions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(1):142–3.

Miehsler W, Weichselberger M, Offerlbauer-Ernst A, et al. Which patients with IBD need psychological interventions? A controlled study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(9):1273–80.

Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. SF-36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand. Handanweisung. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1998.

Ulvik B, Bjelland I, Hanestad BR, Omenaas E, Wentzel-Larsen T, Nygård O. Comparison of the short form 36 and the hospital anxiety and depression scale measuring emotional distress in patients admitted for elective coronary angiography. Heart Lung. 2008;37(4):286–95.

Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994.

Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1997.

Ware J. The SF-36 Health Survey. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 337–45.

Herrmann C. International experiences with the hospital anxiety and depression scale – a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(1):17–41.

De Smedt D, Clays E, Doyle F, et al. Validity and reliability of three commonly used quality of life measures in a large European population of coronary heart disease patients. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(5):2294–9.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Rozanski A. Integrating psychologic approaches into the behavioral management of cardiac patients. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S67–73.

Ketterer MW, Knysz W, Keteyian SJ, et al. Cardiovascular symptoms in coronary-artery disease patients are strongly correlated with emotional distress. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(3):230–4.

Kubzansky LD, Davidson KW, Rozanski A. The clinical impact of negative psychological states: expanding the spectrum of risk for coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S10–4.

Brody D, Khaliq A, Thompson T. Patients’ perspectives on the management of emotional distress in primary care settings. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):403–6.

Baum A, Garofalo J, Yali A. Socioeconomic status and chronic stress. Does stress account for SES effects on health? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:131–44.

Jorm A, Windsor T, Dear K, Anstey K, Christensen H, Rodgers B. Age group differences in psychological distress: the role of psychosocial risk factors that vary with age. Psychol Med. 2005;35(9):1253–63.

Herrmann AS, Huber D. Was macht stationäre Psychotherapie erfolgreich? Der Einfluss von Patienten- und Behandlungsmerkmalen auf den Therapieerfolg in der stationären Psychotherapie. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2013;59:273–89.

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Public attitude towards psychiatric treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94(5):326–36.

Ha JF, Anat DS, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38–43.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

E. Kunschitz, O. Friedrich, C. Schöppl, T. Weiss, W. Miehsler, J. Sipötz and G. Moser declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kunschitz, E., Friedrich, O., Schöppl, C. et al. Assessment of the need for psychosomatic care in patients with suspected cardiac disease. Wien Klin Wochenschr 129, 225–232 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-016-1050-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-016-1050-5