Abstract

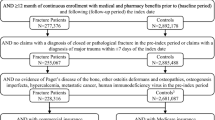

The objective of this study was to estimate the fracture-related direct medical costs during the first year following a fragility nonvertebral fracture in a managed care setting. This was a retrospective cohort study conducted among patients (aged 45+ years) with a primary diagnosis for a fragility nonvertebral fracture between July 1, 2000, and December 31, 2000, using MarketScan, an integrated administrative, medical, and pharmacy claims database. All patients had 6 months of observation prior to their fracture and 12 months following a nonvertebral fracture. Fracture-related direct medical costs were evaluated in the 12-month period following fracture diagnosis using 2003 Medicare fee schedule payments. The costs per fracture per year (PFPY) for specific nonvertebral fracture sites were determined, as well as costs by type of care (i.e., outpatient, inpatient, and other). A total of 4,477 women and men fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The sample was comprised of 73% women and the mean age was 70 years. The most prevalent nonvertebral fracture sites were wrist/forearm (37%), hip (25%), and humerus (15%). Mean total costs per patient per year were highest for fractures of the hip ($26,856), femur ($14,805), tibia ($10,224), and pelvis ($10,198). On average, 84% of the annual fracture-related costs were inpatient; 3% were outpatient, and 13% were long-term care and other costs. In a patient population aged 45+ years, the first month following a nonvertebral fracture has a major impact on medical care costs. The most costly nonvertebral fracture sites were hip, femur, and tibia fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Melton LJ (2003) Adverse outcomes of osteoporotic fractures in the general population. J Bone Miner Res 18(6):1139–1141

Melton LJ (2000) Who has osteoporosis? A conflict between clinical and public health perspectives. J Bone Miner Res 15:2309–2314

Johnell O (1997) The socioeconomic burden of fractures: today and in the 21st century. Am J Med 103(2A):S20–25

Gabriel SE, Tosteson ANA, Leibson CL, Crowson CS, Pond GR, Hammond CS, Melton LJ (2002) Direct medical costs attributable to osteoporosis fractures. Osteoporos Int 13:323–330

Melton LJ, Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Tosteson ANA, Johnell O, Kanis JA (2003) Cost-equivalence of different osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 14(5):383–388

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services files for 2003 Medicare payment systems (www.cms.hhs.gov) (2003) Prospective Payment System (PPS), Physician Fee Schedule Payment Amount, SNF Prospective Payment Rates

Zethraeus N, Stromberg L, Jonsson B, Svensson O, Ohlen G (1976) The cost of a hip fracture: Estimates for 1,709 patients in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand 8:13–17

Brainsky A, Glick H. Lydick E et al (1997) The economic cost of hip fracture in community-dwelling adults: A prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc 45:281–287

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Mason, OH, and Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Bridgewater, NJ

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: ICD-9-CM codes selected for nonvertebral fractures

Appendix: ICD-9-CM codes selected for nonvertebral fractures

Fractures were identified using the fracture-related International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes.

ICD-9-CM codes selected for non-vertebral fractures

Fracture site | ICD-9-CM | |

|---|---|---|

Clavicle (closed) | Closed | 810.0x |

Closed/open not indicated | 810 | |

Fermur (closed) | Pathologic | 733.15 |

Shaft/unspecified | 821.0x | |

Lower end | 821.2x | |

Closed/open not indicated | 821 | |

Hip (closed) | Pathologic | 733.14 |

Transcervical | 820.0x | |

Pertrochanteric | 820.2x | |

Unspecified | 820.8x | |

Closed/open not indicated | 820 | |

Humerus (closed) | Pathologic | 733.11 |

Upper end | 812.0x | |

Shaft/unspecified | 812.2x | |

Lower end | 812.4x | |

Closed/open not indicated | 812 | |

Pelvis (closed) | Acetabulam | 808.0x |

Pubis | 808.2x | |

Other specified | 808.4x | |

Unspecified | 808.8x | |

Closed/open not indicated | 808 | |

Tibia/fibula (closed) | Pathologic | 733.16 |

Upper end | 823.0x | |

Shaft | 823.2x | |

Unspecified | 823.8x | |

Closed/open not indicated | 823 | |

Wrist/forearm (closed) | Pathologic | 733.12 |

Upper end | 813.0x | |

Shaft | 813.2x | |

Lower end | 813.4x | |

Unspecified | 813.8x | |

Closed/open not indicated | 813 | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ohsfeldt, R.L., Borisov, N.N. & Sheer, R.L. Fragility fracture-related direct medical costs in the first year following a nonvertebral fracture in a managed care setting. Osteoporos Int 17, 252–258 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-1993-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-1993-2