Abstract

Purpose

Childhood adversities (CAs) have consistently been associated with mental health problems in childhood and adulthood. However, few studies have employed appropriate statistical methods that take into account overlap among CAs, and many of the ones that did so were based on insufficiently complex models. The present paper studies the prevalence of a wide variety of CAs, as well as their relationship to the onset of mental disorders in a representative sample of a Spanish population.

Methods

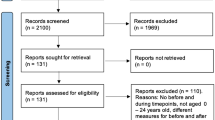

The study is part of the ESEMeD-Spain project, a cross-sectional household survey, which included a nationally representative sample of the Spanish adult population. CAs’ associations with lifetime prevalence of mental disorders were estimated using discrete-time survival analysis with person-years as the unit of analysis.

Results

Of our sample, 20.6 % reported at least one CA, of whom 24 % reported more than one CA. Parental death, parental mental disorder, family violence, economic adversity, physical and sexual abuse were associated with different groups of mental disorders. CAs were associated with the onset of mental disorders during several stages of life. Simulations suggest that CAs were associated with 12.6 % of all disorders, 10.8 % of mood disorders, 5.8 % of anxiety disorders, 27 % of substance disorders and 29.7 % of externalising disorders.

Conclusions

Prevalences of CAs in the Spanish population are lower than those found in other high-income countries, especially when compared to the USA. In Spain, different CAs were associated with the onset of a number of mental disorders, although these associations were not as frequent as in other countries. Although lower than in other countries, the association between CAs and mental health in Spain should be considered relevant. Specific health policies and prevention programmes are needed in order to decrease this burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CAs:

-

Childhood adversities

- CIDI:

-

Composite international diagnostic interview

- ESEMeD:

-

European study of epidemiology of mental disorders

References

Higgins DJ, McCabe MP (2001) Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: adult retrospective reports. Aggress Violent Behav 6(6):547–578

Borges G, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME, Orozco R, Molnar BE, Nock MK (2008) Traumatic events and suicide-related outcomes among Mexico City adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(6):654–666

Thabet AAM, Vostanis P (1999) Post-traumatic stress reactions in children of War. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(3):385–391

Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP (1996) The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: a community study. Child Abuse Negl 20(1):7–21

Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M (2003) The long-term health outcomes of childhood abuse: an overview and a call to action. Journal of General Internal Medicine 18(10):864–870 (pii) 20918

Benjet C (2010) Childhood adversities of populations living in low-income countries: prevalence, characteristics, and mental health consequences. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 23(4):356–362. doi:310.1097/YCO.1090b1013e32833ad32879b

Von Korff M, Alonso J, Ormel J, Angermeyer M, Bruffaerts R, Fleiz C, de Girolamo G, Kessler RC, Kovess-Masfety V, Posada-Villa J, Scott KM, Uda H (2009) Childhood psychosocial stressors and adult onset arthritis: broad spectrum risk factors and allostatic load. Pain 143(1–2):76–83

Paolucci EO, Genuis ML, Violato C (2001) A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of child sexual abuse. J Psychol 135(1):17–36

Malinoski-Rumell R, Hansen DJ (1993) Long-term consequences of childhood physical abuse. Psychol Bull 114(1):68–79

Fristad MA, Jedel R, Weller RA, Weller EB (1993) Psychosocial functioning in children after the death of a parent. Am J Psychiatry 150(3):511–513

Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA (2007) Poly-victimization: a neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse Negl 31:7–26

Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS (1997) Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med 27:1101–1119

Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Loo CM, Giles WH (2004) The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl 28(7):771–784

Ney P, Fung T, Wickett A (1994) The worst combinations of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl 18(9):705–715

Kinard EM (1994) Methodological issues and practical problems in conducting research on maltreated children. Child Abuse Negl 18(8):645–656 (pii: 0145-2134(94)90014-0)

Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, O’Brien N (2007) Differential correlates of multi-type maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abuse Negl 31(4):393–415

Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Gore S (2007) Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health 7(1):30

Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Williamson DF, Dube SR, Brown DW, Giles WH (2005) Childhood residential mobility and multiple health risks during adolescence and adulthood: the hidden role of adverse childhood experiences. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 159(12):1104–1110

Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH (2001) Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. JAMA 286:3089–3096

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14(4):245–258

Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF (2003) Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. Am J Psychiatry 160(8):1453–1460

Fox KM, Gilbert BO (1994) The interpersonal and psychological functioning of women who experienced childhood physical abuse, incest, and parental alcoholism. Child Abuse Negl 18(10):849–858

Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Gore S (2008) The impact of cumulative childhood adversity on young adult mental health: measures, models, and interpretations. Soc Sci Med 66(5):1140–1151

Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC (2010) Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication i: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(2):113–123. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186

Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, De Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, De Girolamo G, Gluzman S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Kawakami N, Karam A, Levinson D, Medina Mora ME, Oakley Browne MA, Posada-Villa J, Stein DJ, Him Adley Tsang C, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Berglund P, Gruber MJ, Petukhova M, Chatterji S, Üstün TB (2007) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 6:168–176

Reher DS (1998) Family Ties in Western Europe: persistent Contrasts. Popul Dev Rev 24(2):203–234

Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alhamzawi AO, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Benjet C, Bromet E, Chatterji S, de Girolamo G, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Florescu S, Gal G, Gureje O, Haro JM, CY Hu, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lepine J-P, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Tsang A, Ustun TB, Vassilev S, Viana MC, Williams DR (2010) Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry 197(5):378–385. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499

Haro JM, Palacin C, Vilagut G, Romera B, Codony M, Autonell J, Ferrer M, Ramos J, Kessler R, Alonso J (2003) Epidemiology of mental disorders in Spain: methods and participation in the ESEMeD-Spain project. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría 31(4):182–191 (pii: 31110413)

Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, Girolamo G, Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, Haro JM, Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Kovess V, Lépine JP, Ormel J, Polidori G, Russo LJ, Vilagut G, Almansa J, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Autonell J, Bernal M, Buist-Bouwman MA, Codony M, Domingo-Salvany A, Ferrer M, Joo SS, Martínez-Alonso M, Matschinger H, Mazzi F, Morgan Z, Morosini P, Palacín C, Romera B, Taub N, Vollebergh WAM (2004) Sampling and methods of the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109(s420):8–20

Kessler RC, Ustun TB (2004) The world mental health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int J Meth Psychiatr Res 13(2):93–121

Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine JP, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC (2006) Concordance of the composite international diagnostic interview version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Int J Meth Psychiatr Res 15(4):167–180

Simon GE, VonKorff M (1995) Recall of psychiatric history in cross-sectional surveys: implications for epidemiologic research. Epidemiol Rev 17(1):221–227

Knauper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC (1999) Improving the accuracy of major depression age of onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Meth Psychiatr Res 8(1):39–48

Endicott J, Andreasen N, Spitzer RL (1978) Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York

Kendler KS, Silberg JL, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ (1991) The family history method: whose psychiatric history is measured? Am J Psychiatry 148(11):1501–1504

Straus MA (1979) Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the conflict tactics (CT) scales. J Marriage Fam 41(1):75–88

Willett JB, Singer JD (1993) Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol 61(6):952–965

Szklo M, Nieto J (2003) Epidemiologia intermedia: Conceptos y aplicaciones. Díaz de Santos, Madrid

Wolter KM (ed) (1985) Introduction to variance estimation. Springer-Verlag, New York

SUDAAN (2002) Professional Sofware for Survey Data Analysis 8.0.1 edn. Research Triangle Institute, Durham

Fujiwara T, Kawakami N, World Mental Health Japan Survey G (2011) Association of childhood adversities with the first onset of mental disorders in Japan: results from the World Mental Health Japan, 2002–2004. J Psychiatr Res 45(4):481–487

Iborra I (2008) Maltrato de personas mayores en la familia en España. Centro Reina Sofia, Valencia

Kokanovic R (2011) The diagnosis of depression in an international context: the SAGE handbook of mental health and illness. Sage Publications, London

Muñoz M, Pérez-Santos E, Crespo M, Guillén AI (2009) Estigma y enfermedad mental. Análisis del rechazo social que sufren las personas con enfermedad mental, Madrid

Maughan B, McCarthy G (1997) Childhood adversities and psychosocial disorders. Br Med Bull 53(1):156–169

Huth-Bocks AC, Levendosky AA, Semel MA (2001) The Direct and indirect effects of domestic violence on young children’s intellectual functioning. J Fam Violence 16(3):269–290. doi:10.1023/a:1011138332712

Salcido Carter L, Weithorn LA, Behrman RE (1999) Domestic violence and children: analysis and recommendations. Future Children 9:4–20

Ullman SE (2003) A critical review of field studies on the link of alcohol and adult sexual assault in women. Aggress Violent Behav 8:471–486

Fantuzzo J, Boruch R, Beriama A, Atkins M, Marcus S (1997) Domestic violence and children: prevalence and risk in five major US cities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:116–122

Jaffe PG, Hurley DJ, Wolfe D (1990) Children’s observations of violence: I. critical issues in child development and intervention planning. Can J Psychiatry/La Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 35(6):466–470

Spaccarelli S, Sandler IN, Roosa M (1994) History of spouse violence against mother: correlated risks and unique effects in child mental health. J Fam Violence 9(1):79–98. doi:10.1007/bf01531970

Straus MA, Gelles RJ, Steinmetz SK (eds) (1980) Behind closed doors: violence in the American family. Anchor, New York

Banyard VL, Williams LM (2007) Women’s voices on recovery: a multi-method study of the complexity of recovery from child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl 31(3):275–290

Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, Maughan B (2007) Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse Negl 31(3):211–229

DuMont KA, Widom CS, Czaja SJ (2007) Predictors of resilience in abused and neglected children grown-up: the role of individual and neighborhood characteristics. Child Abuse Negl 31(3):255–274

Heller SS, Larrieu JA, D’Imperio R, Boris NW (1999) Research on resilience to child maltreatment: empirical considerations. Child Abuse Negl 23(4):321–338

Benard B (2006) Using Strengths-based practice to tap the resilience of families: Strengths Perspective in Social Work Practice. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

Scocco P, de Girolamo G, Vilagut G, Alonso J (2008) Prevalence of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts and related risk factors in Italy: results from the European Study on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders–World Mental Health study. Compr Psychiatry 49(1):13–21

Sameroff AJ (2000) Developmental systems and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 12:297–312

McMahon SD, Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, Ey S (2003) Stress and psychopathology in children and adolescents: is there evidence of specificity? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 44(1):107–133

Shanahan L, Copeland W, Costello EJ, Angold A (2008) Specificity of putative psychosocial risk factors for psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(1):34–42

Díaz-Huertas J, Vall-Combelles O, Ruiz-Díaz M (2004) Informe técnico sobre problemas de salud y sociales de la infancia en España. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Madrid

Crosier T, Butterworth P, Rodgers B (2007) Mental health problems among single and partnered mothers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42(1):6–13

Quinton D (1989) Adult consequences of early parental loss. BMJ 299:694–695

Bowlby J (ed) (1980) Attachment and Loss, vol 3. Basic Books, New York

Bowlby J (ed) (1988) A secure base: clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge, London

Duncan G, Brooks-Gunn J (1997) Consequences of growing up poor. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Kendall GE, Li J (2005) Early childhood socialization and social gradients in adult health: a commentary on Singh-Manoux and Marmot’s “role of socialization in explaining social inequalities in health” (60: 9, 2005, 2129–2133). Soc Sci Med 61 (11):2272–2276; discussion 2277–2279

Poulton R (2005) Commentary: how does socioeconomic disadvantage during childhood damage health in adulthood? Testing psychosocial pathways. Int J Epidemiol 34(2):344–345

Montgomery SM, Bartley MJ, Cook DG, Wadsworth ME (1996) Health and social precursors of unemployment in young men in Great Britain. J Epidemiol Community Health 50(4):415–422

Cummings EM, El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Buckhalt JA (2009) Children and violence: the role of children’s regulation in the marital aggression-child adjustment link. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 12:3–15

Gelles RJ, Cavanaugh MM (2005) Violence, abuse and neglect in families and intimate relationships. In: Price SJ, McHenry PC (eds) Families & change: coping with stressful events and transitions. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 129–154

Horwitz AV, Widom CS, McLaughlin J, White HR (2001) The impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health: a prospective study. J Health Soc Behav 42(2):184–201

Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Kokaua J, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Poulton R (2010) How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med 40(06):899–909. doi:10.1017/S0033291709991036

Hardt J, Rutter M (2004) Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45(2):260–273

Schraedley PK, Turner RJ, Gotlib IH (2002) Stability of retrospective reports in depression: traumatic events, past depressive episodes, and parental psychopathology. J Health Soc Behav 43:307–316

Hetherington EM, Stanley-Hagan M (1999) The adjustment of children with divorced parents: a risk and resiliency perspective. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(1):129–140

Bond L, Carlin JB, Thomas L, Rubin K, Patton G (2001) Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. BMJ 323(7311):480–484

World Health Organization (2006) Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence. WHO, Geneva

Frazzetto G, Di Lorenzo G, Carola V, Proietti L, Sokolowska E, Siracusano A, Gross C, Troisi A (2007) Early trauma and increased risk for physical aggression during adulthood: the moderating role of MAOA genotype. PLoS One 2(5):e486

Kaufman J, Yang B-Z, Douglas-Palumberi H, Crouse-Artus M, Lipschitz D, Krystal JH, Gelernter J (2007) Genetic and Environmental Predictors of Early Alcohol Use. Biol Psychiatry 61(11):1228–1234

Espejo E, Hammen C, Connolly N, Brennan P, Najman J, Bor W (2007) Stress sensitization and adolescent depressive severity as a function of childhood adversity: a link to anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol 35(2):287–299

Cotter PA (1998) Sexual abuse is not the only childhood adversity that may lead to later depression. Br Med J 316:1244

Finkelhor D (1995) The victimization of children: a developmental perspective. Am J Orthopsychiatry 65:177–193

Tennant C, Hurry J, Bebbington P (1982) The relation of childhood separation experiences to adult depressive and anxiety states. Br J Psychiatry 141(5):475–482. doi:10.1192/bjp.141.5.475

Pirkola S, Isometsä E, Aro H, Kestilä L, Hämäläinen J, Veijola J, Kiviruusu O, Lönnqvist J (2005) Childhood adversities as risk factors for adult mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40(10):769–777

Stansfeld SA, Clark C, Rodgers B, Caldwell T, Power C (2010) Repeated exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage and health selection as life course pathways to mid-life depressive and anxiety disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46(7):549–558

Korkeila K, Korkeila J, Vahtera J, Kivimäki M, Kivelä S-L, Sillanmäki L, Koskenvuo M (2005) Childhood adversities, adult risk factors and depressiveness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40(9):700–706

Molnar B, Buka S, Kessler R (2001) Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health 91(5):753–760

Acknowledgments

The ESEMeD project (http://www.epremed.org) was funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5- 1999-01042; SANCO 2004123); the Piedmont Region, Italy; Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028-02); Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE); Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The ESEMeD survey was carried out in conjunction with the WMHS Initiative. Our thanks to the WMHS staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884, MH077883), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, the Eli Lilly & Company Foundation, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol- Myers Squibb, and Sanofi Aventis. A complete list of WMHS publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. Dr C. G-F is grateful to the Juan de la Cierva FSE (JCI-2009-05486) programme for their support. J.P. is grateful to the Instituto de Salud Carlos III for a predoctoral grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

Methods of assessing childhood adversities

Physical abuse

Respondents were classified as having experienced physical abuse when they indicated that, when they were growing up, their father or mother (includes biological, adoptive or step-parent) slapped, hit, pushed, grabbed, shoved or threw something at them, or that they were beaten up as a child by the persons who raised them.

Sexual abuse

For sexual abuse, the following questions were asked: “The next two questions are about sexual assault. The first is about rape. We define this as someone either having sexual intercourse with you or penetrating your body with a finger or object when you did not want them to, either by threatening you or using force, or when you were so young that you didn’t know what was happening. Did this ever happen to you?”. Or alternatively: “Other than rape, were you ever sexually assaulted or molested?” Sexual abuse was the only adversity where information was not collected that would distinguish whether the perpetrator was a family member or someone else. However, previous research using a similar measure, but which did allow such a distinction, showed that a good indirect way to distinguish family versus non-family sexual abuse was to ask about number of instances of victimisation, with cases involving one or two instances typically perpetrated by a stranger and those involving three or more instances typically perpetrated by a family member [89]. In the WMHS, respondents who reported that any of these experiences occurred to them three times or more were classified as having experienced sexual abuse (within the family context).

Parental death and other parental loss

For parental death or other parental loss, respondents were first asked whether they lived with both of their parents when they were growing up. If respondents replied in the negative, they were asked: “Did your biological mother or father die, or was there some other reason?” According to their answers to these questions, respondents were classified as having experienced parental death (i.e. when they indicated that one or both parents died), and other parental loss (i.e. when respondents replied that they were either adopted, went to boarding school, were in foster care, or that they left home before the age of 16).

Parental mental illness

For parental mental illness, the following questions were asked. Parental depression was assessed by the following items: “During the years you were growing up, did the person who raised you ever have periods lasting 2 weeks or more where she was sad or depressed most of the time?” and “During the time when his/her depression was at its worst, did he/she also have other symptoms like low energy, changes in sleep or appetite, and problems with concentration?” Parental generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) was assessed as follows: “During the time you were growing up, did the person who raised you ever have periods of a month or more when he/she was constantly nervous, edgy, or anxious?” and “During the time his/her nervousness was at its worst, did he/she also have other symptoms like being restless, irritable, easily tired, and difficulty falling asleep?” Parental panic disorder was assessed by the following item: “Did the person who raised you ever complain about anxiety attacks where all of a sudden she felt frightened, anxious, or panicky?” Respondents who replied positively on the diagnostic items for any of these mental disorders were then asked whether these symptoms a) occurred at all or most of the time, b) interfered a lot with the life or activities of the parent or the person who raised the respondent, c) whether their parents sought professional help for this problem. If respondents replied affirmatively on c), and either on a) or b), they were coded as respondents with parental depression, GAD, or panic disorder.

Parental substance disorder

Similarly, parental substance disorder was assessed with the following items: (criterion a) “Did the person who raised you ever had a problem with alcohol or drugs?” and (criterion b) “Did he/she have this problem during all, most, some or only a little of your childhood?” Respondents who replied positively on the first and “all” and “most” on the second item were then asked whether the problem interfered a lot with life or activities of the man or woman who raised the respondent (criterion c), or whether they had sought professional help for this problem (criterion d). Those respondents who replied affirmatively on criteria (a) and (b) and on either (c) or (d) were coded as having had parents with a substance disorder.

Parental criminal behaviour

Parental criminal behaviour was assessed by the following questions: “Was the person who raised you ever involved in criminal activities like burglary or selling stolen property?” and “Was the person who raised you ever arrested or sent to prison?” Respondents who replied positively on either question were classified as having experienced criminal behaviour in the family.

Family violence

Respondents were coded as having experienced family violence when they indicated that they “were often hit, shoved, pushed, grabbed or slapped while growing up” or “witnessed physical fights at home, like when your father beat up your mother”.

Economic adversity

Family economic adversity was coded positive if there was a positive response to either item (a) or item (b). Item (a) was: “During your childhood and adolescence, was there ever a period of 6 months or more when your family received money from a government assistance programme like Welfare, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, General Assistance, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families?” (This item was modified to be relevant to the welfare programmes in each country where the survey was administered). Item (b) was: If there was no male head of the family and the female head did not work all or most of the time during respondent’s childhood; or if there was no female head of the family and the male head did not work all or most of respondent’s childhood, or if there was no female head and no male head of the family.

Physical illness

The respondents were asked whether, during their childhood, they had any chronic condition that appeared on a list. Examples of the chronic conditions listed are diabetes, epilepsy and cancer. If the respondent answered affirmatively, the age at which the chronic condition was first diagnosed was asked. If the informant was diagnosed before age 18 and the interference of that condition was high or extreme, the respondent was classified as having this adversity.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perales, J., Olaya, B., Fernandez, A. et al. Association of childhood adversities with the first onset of mental disorders in Spain: results from the ESEMeD project. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48, 371–384 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0550-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0550-5