Abstract

Food price volatility—and in particular price spikes—can create serious problems for vulnerable individuals and groups. One quick, simple approach for governments to deal with this problem is to insulate their domestic market from changes in world prices. It turns out that many governments do this to a large degree, resulting in their domestic prices becoming much less volatile than world market prices. But if changes in international prices are sustained for a few years, policymakers appear to pass through most of these changes. Such sustained increases in food prices appear to be helpful in reducing poverty and to have had favorable impacts on global poverty since 2006. To individual policymakers, this approach of using short-term insulation and long-term pass-through seems to be very practical and useful, even though they know that insulation measures, like export restrictions and import tariff reductions, are beggar-thy-neighbor policies. Collectively, however, this policy approach appeared to be ineffective in reducing poverty during the 2006–2008 price spikes because price insulation contributed substantially to increasing food price volatility.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Codes

1 Introduction

Changes in food prices have extremely important impacts on poor and vulnerable households. Although some households benefit from higher food prices, others are adversely affected, depending whether they are net buyers or sellers of food and the extent to which their incomes adjust to food price changes. Low-income households tend to spend a large share of their incomes on staple foods, making them potentially vulnerable to food price increases. Policymakers in many countries respond to food price changes—and particularly food price increases—by insulating their countries from these developments. Exporters often achieved this insulation by restricting export, whereas importers most commonly respond by reducing import barriers. While individually rational, these responses create a collective action problem—each country’s actions contribute to a further rise in world prices—exactly the problem that they are individually trying to avoid.

Our concern in this chapter is with the impact of food prices and policies on the poorest in the society. We focus on the impacts of food price changes on individual households, particularly on those living near the poverty line. One very simple indicator of the effect at the household level is the change in the number of people living below the poverty line. We focus primarily on the World Bank’s standard measure of poverty, which is defined as US$1.25 per day in international purchasing power. An economic shock that increases the number of people below the poverty line is clearly an adverse development. We then consider governments’ policy responses to economic shocks and their effects on the welfare of individual households, and hence on the number of households below the poverty line. Finally, we discuss the implications of countries’ trade policy choices—initially from the viewpoint of an individual country and then from the viewpoint of all countries.

2 Effects of Food Price Changes on Poverty

One widely accepted measure of the short-run effect of a small change in a commodity price on household welfare is given by the household’s net trade share for that good, as defined by Deaton (1989). A household that is a net seller of a good benefits when the price of that good rises. By contrast, a household that is a net buyer is put at a disadvantage when the price rises. This is only an approximation as demand can respond very quickly, but given the magnitude of the relevant demand elasticities, the associated second-order impact is quite small. Therefore, the first-order measure is a good approximation. Essentially, this is the same measure that is used here for determining the effect of a change in prices on national income (see Martin 1997 for a fuller discussion). The concept of short run used in this analysis is the length of time in which other effects, such as output adjustment or effects on wages, do not arise. Some analyses, such as that by Ravallion (1990), suggest that much of the longer-run impact is felt after 3 years.

At the household level, there are some important stylized facts that influence the likely effect of this measure. Perhaps the oldest of such stylized facts is that poor households spend a large share of their incomes on food. This might suggest that the poor are always put at a disadvantage when food prices rise. However, this need not be the case because most of the world’s poor population live in rural areas, and the majority of them earn their living from agriculture. Nevertheless, many farmers in developing countries are also net buyers of food. Thus, the short-run effect of food prices on poverty becomes an empirical question that can be resolved only by using detailed data on the income sources and expenditure patterns of households.

A great deal of evidence shows that short-run increases in most food prices, other things equal, raise the poverty level in most developing countries (see, for example, de Hoyos and Medvedev 2011; Ivanic and Martin 2008; Ivanic et al. 2012; Jacoby 2013; Wodon and Zaman 2010). This is often the case even in countries that are net food exporters and therefore benefit from the terms-of-trade effect of the shock (see Ferreira et al. 2013, for Brazil). In some countries, such as Vietnam, where agricultural resources are relatively evenly distributed, higher prices of key products such as rice may lower the poverty level (Ivanic and Martin 2008). Similarly, higher milk prices appear to lower poverty in Peru. This is because the milk producers are much poorer than their customers. The net increase in poverty associated with a food price rise does not mean that all people are adversely affected. For example, Ivanic et al. (2012) found that although higher prices resulted in a net increase in the number of people living in extreme poverty by 44 million in 2010, 68 million people fell below the poverty line, and 24 million rose above it.

Once markets are given more time to adjust to changes, two additional factors need to be considered. First, changes in food prices may result in changes in factor returns. Second, changes in the output patterns of poor households may occur. The factor return which is most likely to affect poor households is the wage rate paid for unskilled labor sold by the households outside their farm (Lasco et al. 2008; Ravallion 1990). The effect on wage rates is likely to be much more important when the product is (a) very labor intensive; (b) has a large share of output, as with rice in Bangladesh; and (c) involves intensive use of intermediate inputs.

2.1 Short-Run Effects

The available evidence suggests that the full effect of food price changes on wage rates and output volumes takes time to materialize. A useful measure of the short-run effects of higher food prices on poverty considers only the direct impact on incomes due to the initial net trade position of households. The sign of this measure is an important building block of longer-term measures that also consider wage rates and output change effects. These measures are, of course, potentially vulnerable to mismeasurement of the initial production or consumption levels of the households—an issue which requires further research (Headey and Fan 2010, p. 72; Carletto 2012). The measures should also take into account a small second-order impact—the ability of consumers to adjust their consumption in response to price changes. Given the low value of compensated demand elasticities in small countries, this refinement makes very little difference to the estimated impacts. Table 5.1 presents the results of a simulation analysis of these short-run effects based on survey data from 31 countries (Ivanic and Martin 2014a). Two key features of this analysis need to be taken into account. First, these results are based on a broad food price index, rather than price changes for any particular food. Second, they are based on a specific type of price change—one that results from shocks outside the developing countries studied. This is a realistic approach for analyzing an event such as the food price shock in 2006–2008, which was primarily caused by external factors, such as the sharp increase in demand for foodstuffs from the biofuel sector in industrial countries (Wright 2014).

Table 5.1 shows that increases in food prices adversely affect the poor in most countries except Albania, Cambodia, China, and Vietnam; in these countries, a 10 % increase in food prices reduces the poverty level. Strikingly, the relationship between poverty effects and food price changes is frequently highly nonlinear. In Albania and Vietnam, food price changes have favorable impacts on near-poor net sellers of food; some of them rise above the poverty line when faced with a small food price increase. In contrast, net buyers of food are negatively affected by larger price increases, resulting in them falling below the poverty line. For most countries, the effects are monotonic, but the relationship between price change and poverty is frequently nonlinear. The poor population in countries, such as India, Indonesia, and Pakistan are severely affected by price changes.

The results presented in Table 5.1 were used to represent the global effects of price changes on poverty. The study followed the sampling methodology outlined in Ivanic et al. (2012). The global impacts are presented in the final row of the table. They provide a useful summary of the effects of price changes: global poverty rises despite a decline in poverty in important countries such as China and Vietnam.

2.2 Longer-Run Effects

As noted above, the longer-run effects of food price change differ from the short-run effects for two main reasons: (a) the effects of food price changes on wages and (b) the change in output volume resulting from the food price increase (i.e., the supply response). In our earlier work about the effects of food prices on poverty, we focused on the short-run effects, taking into account potential short-run wage changes (Ivanic and Martin 2008).

In our more recent work, we have also examined the longer-run effects, considering both changes in wage rates and changes in the quantities of output supplied (Ivanic and Martin 2014a). In this chapter, we wanted to assess the implications of food price changes on the wage rates of unskilled labor. The goal is to capture the impacts of price changes for a range of commodities; therefore, we could not rely on the type of econometric models used in Ravallion (1990). Instead, we developed a model, which is similar to the production module of the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) model, for each country. These models are very similar in structure to the workhorse Heckscher–Ohlin model used in international trade theory (Caves and Jones 1973, pp. 182–185): The output in each sector is determined by the level of a composite factor input, and the substitution between factors that constitute the composite factor input follows a constant-elasticity-of-substitution technology. The version we used also considers the real-world phenomenon of intermediate inputs, which magnify the impacts of output-price changes on factor returns.

In medium-run analyses, all factors except labor are fixed in each sector, and changes in output come about through intersectoral movements of labor. In the longer run, we took into account movements of labor and capital in a manner consistent with the Heckscher–Ohlin model of trade, modified to make allowance for the real-world imperfect mobility of land between sectors. The resulting elasticities of wage rates with respect to the prices of agricultural goods vary by country, but they are typically around unity for increases in all agricultural prices. To remain consistent with the economy-wide analysis which is used to estimate the wage effects of food price changes, we used the structure of the GTAP general equilibrium model to represent the response of households, which allocate their available resources between the commodities that they produce.

The impacts of commodity prices on wages (Stolper–Samuelson effects) used in this analysis were derived from simulation models for individual economies rather than the direct estimation of statistical relationships. This is the only feasible approach given our need to assess the impacts of price changes by a specific commodity and at the global level. In an important study, Jacoby (2013) developed similar simple simulation models of the production side of the economy (in his case, for regions in India). He showed from first principles that the impacts of food price changes on wages depend upon key parameters, such as the importance of a commodity in labor demand, and the share of intermediate inputs in production. He also tested whether the impacts of food prices on wages were consistent in scale with econometrically based estimates. The study concluded that the impacts were consistent with the estimates and that the test used in the study has considerable significance.

The price elasticities of wages used in our study average slightly above one for a broadly defined food group, which includes not just basic staples but also processed foods (Ivanic and Martin 2014a, p. 36). As expected, the price elasticities of unskilled wages tend to be relatively large with respect to food prices for the most important commodities. In many cases, the commodities with the greatest impact are dominant staples like rice in Bangladesh and cassava in Nigeria. The group “Other Processed Foods” is more important in many cases because this is a large commodity group and the models take into account the labor used in food processing.

When considering a much wider coverage of foods, the results from our study are consistent with those from Jacoby (2013) for India using cross-sectional data and the global results in Headey (2014). Ravallion (1990), and Boyce and Ravallion (1991) estimated that the elasticity of the agricultural wage rate in Bangladesh to the price of rice was 0.22 in the short run and 0.47 in the long run. The long-run elasticity is quite similar to the estimate of 0.4 used in Ivanic and Martin (2014a) for rice in Bangladesh. Lasco et al. (2008) found a largely similar long-run estimate of 0.57 for rice in the Philippines.

Headey’s (2015) analysis found that food prices had a considerably smaller impact on urban wages in Ethiopia, with preferred elasticities of around 0.3. This result may suggest the presence of barriers between urban and rural markets for unskilled workers. Assessing the implications of higher food prices on wages, Ivanic and Martin (2008) suggested that the overall poverty impact of higher food prices would likely only be slightly affected by such barriers. The barriers are significant in rural areas, where the population tends to be poorer; the benefits of higher wages for net-labor-selling households are concentrated mostly in these areas. When the barriers are not significant, the benefits of higher wages for unskilled workers are spread across more of the low-income population.

In a study about barriers to agricultural exports, higher agricultural prices (including processed agricultural products such as wine) were found to have a very large impact on wages in Moldova (Porto 2005), with an elasticity of 2.9. Using a symmetry relationship to estimate the parameters, another econometric study found that the food prices had a lower impact on wages in six African countries than the estimates used in this study (Nicita et al. 2014). This resulted in the long-run relationship between food prices and poverty being essentially the same as the short-run relationship for these countries.

Considering the global estimates shown in the first column in Table 5.2, global poverty rises in the short run with increasing food prices. When prices increase by 10 %, global poverty is estimated to rise by 0.8 % points. The rate of increase grows faster as the food price rise increases because so many households near the poverty line spend extremely large shares of their incomes on food. When the food price shock increases fivefold from 10 to 50 %, poverty is predicted to rise by 5.8 % points, and doubling the price shock from 50 to 100 % more than doubles the estimated global poverty estimate to 13 % points.

It is important to understand what causes the simulation results for the short run and the long run to be different, as shown in Table 5.2. The second column shows the results obtained after adding the impact of wage changes to the direct impact of higher food prices. Since selling unskilled labor is a very important source of income for many poor households, and the impacts of higher food prices on wages are found to be substantial for unskilled workers in many countries, it is not surprising that higher wages have important, favorable impacts on poverty. The results obtained for the medium run, in which farmers are able to change their outputs of food commodities, is quite similar to the results in the second column. This implies that the ability to adjust output and transfer labor between agriculture and other sectors has a much smaller impact than the impact of wage changes emphasized by Jacoby (2013). In the longer-run scenario, in which all factors are mobile, the importance of adjustment responses increases, but they remain quite small relative to the impacts of higher wages resulting from food price changes.

3 Policy Responses

A widely observed policy response from developing countries, and historically from today’s industrial countries, to fluctuations in world food prices is to insulate their domestic markets from these changes. When prices surged in 2007–2008, many developing country exporters used export restrictions to lower their domestic prices relative to world prices. Even more countries lowered either their import or their consumption taxes on food (Wodon and Zaman 2010, p. 167). But this response is not confined to instances of sharp price increases. For staple food commodities, such as rice, domestic markets are more or less constantly insulated. Figure 5.1 shows the strong inverse relationship between the world average rate of protection for rice and the world price—a relationship that is consistent with the consistent stabilization of domestic prices relative to world prices.

World prices and the average protection rate for rice. Source: Calculations based on data from http://www.worldbank.org/agdistortions. Note: NRA = nominal rate of assistance. See Anderson (2009)

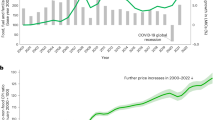

However, the dynamic response pattern for key agricultural commodities appears more complex and interesting. Developing countries tend to adopt an extremely high degree of insulation against rapid changes in food prices but, if these changes are sustained for a period of time, to pass them through domestic markets. This pattern is clearly shown in Fig. 5.2 for the average food price, which takes into account the prices of rice, wheat, maize, edible oils, and sugar. In the case of price increases, this policy seems to be particularly suitable for managing the adverse impacts of higher food prices on the poor in individual countries. But after a while, food prices can feed through into wages, and producers are able to respond by increasing supply, therefore allowing the beneficial impacts of higher food prices on the poor to be noticeable.

Domestic and world price index of rice, wheat, maize, oil, and sugar, developing countries. Source: Ivanic and Martin (2014b)

This policy approach is, for individual countries, an effective way to stabilize their domestic prices. Using trade measures to stabilize domestic prices is very likely to be less costly than using storage policies alone. However, the widespread usage of the approach creates a serious collective action problem. If every country seeks to reduce its price by the same amount, the domestic price is unaffected (Martin and Anderson 2012). The mechanism is simple—export restrictions in exporting countries push up world prices, as do import duty reductions in importing countries. Martin and Anderson (2012) pointed out that the problem is akin to everyone in a stadium standing up to get a better view of a game. Their analysis suggests that almost half of the increase in world rice prices between 2006 and 2008 was the result of countries’ attempting to insulate their markets against the increases in world prices, thus creating a serious collective action problem. Countries that prefer not to use export controls or import barrier reductions in response to a rise in prices may feel compelled to do so because of the actions of other countries, thereby further amplifying the increase in world prices.

In reality, different countries insulate to different extents, and insulation might reduce poverty if the countries which are the most vulnerable to a surge in food prices insulate their domestic markets to a greater degree than the others. For instance, if developing countries insulated their domestic markets and therefore forced the adjustment onto developed countries (which are much more capable of managing this problem), the global poverty effects of a food price surge might be reduced. There are, however, no guarantees that all interventions follow this pattern. Historically, some of the most enthusiastic users of price insulation have been relatively wealthy countries, such as members of the European Community with its pre-Uruguay Round system of variable import levies. To learn whether the pattern of interventions during the 2006–2008 price surge actually reduced poverty, Anderson et al. (2014) examined the actual interventions used and assessed their effects on global poverty, taking into account the effects of the interventions on the world price. They concluded that the interventions appeared to reduce the poverty level by around 80 million people, as long as the effects of the trade interventions on world prices were not taken into account. Once the effects were considered, the intervention generated a small and statistically insignificant increase in world prices.

Many countries try to use a combination of trade and storage measures to reduce the volatility of their domestic prices. In principle, the combination of trade and storage measures is potentially more effective than trade or storage measures alone (Gouel and Jean 2014). Gautam et al. (2014) found that the combination of trade measures, which are beggar-thy-neighbor approaches, and storage measures, which might be beneficial to the neighbors, reduces—but does not eliminate—the adverse effects of one country’s policies on food price volatility in the rest of the world. Implementing these policies tends to be extremely expensive; the policies are also likely to include rigidities that frequently cause them to collapse (Knudsen and Nash 1990).

The central role of the WTO is to deal with collective action problems that affect the level of world prices and/or their volatility. The use of bindings on import tariffs reduces the extent to which importing countries can depress world prices by discouraging imports. The Uruguay Round introduced important measures to discourage the insulation of domestic markets against world price changes, a practice that exacerbates price volatility. The reforms include banning variable import levies and subjecting administered prices to discipline both the market access and domestic support pillars.

Because of its mercantilist focus, the WTO has done very little to discourage the use of export restrictions—from the point of view of an exporter, any export restriction imposed by another exporter represents an export opportunity. While quantitative export restrictions are subjected to a general proscription under Article XI of GATT, export taxes are not constrained except in limited instances, such as restrictions negotiated under WTO accession agreements. But unless all export restrictions are disciplined, they are likely to contribute to upward pressure on food prices in times of crisis, making it difficult for other exporters not to follow suit and for importers to refrain from lowering domestic prices through duty and tax reductions—all of which put further upward pressure on world prices while being collectively ineffective in dealing with the problem. Importantly, constructive suggestions for binding and progressive reduction of export taxes have been put forward (see the discussion in Anderson et al. 2014), but there has not been enough attention on dealing with this collective action problem. Instead, the focus lies on maintaining countries’ rights to contribute to the problem.

4 Recent Developments in Poverty Reduction

A question about the impact of food price increases on poverty, highlighted by Headey and Fan (2010) and Headey (2011), is that poverty appears to have declined sharply between 2006 and 2012 despite food prices rising substantially during that period. If the short-run impacts of higher food prices were as adverse as suggested by short-run simulation studies, then how could poverty have continued to decline between 2006 and 2012? Recent studies about the difference between the short- and long-run impacts of food price changes, and the pattern of transmission of food price increases may offer an explanation for this question.

A recent study by the authors (Ivanic and Martin 2014b) found that price transmission was very low in the initial phase of a food price increase. This reduced the adverse impacts of higher domestic food prices on poverty while exacerbating the increase in world food prices. With a sustained increase in world prices, domestic prices begin to rise over a time frame in which wage responses are able to take effect. When the results on world food price changes, food price transmission and food price impacts on poverty are brought together, as in Table 5.2, we found that the food price increases between 2006 and 2012 were likely to have contributed substantially to the large reduction in poverty observed over this period. According to projections, poverty will have declined by 8 % between 2006 and 2015; to which food price increases may have contributed 5 % points. Clearly, these numbers should be interpreted with caution, particularly because the figure for 2015 is only a projection (Fig. 5.3).

5 Conclusions

This chapter has examined the critical issue of the short- and long-term welfare effects of food price changes, and the associated policy responses. It has focused on the effect of food price changes on individuals and households. As shown by Ferreira et al. (2013) for Brazil, many people may be adversely affected by food price changes even when their country as a whole benefits from the change. The evidence surveyed here strongly suggests that a rise in food prices will result in a net increase in poverty in the short run. Inevitably, some net sellers of food are able to rise out of poverty, while some net buyers of food fall into poverty. But, in most countries, the number of people falling into poverty is greater than the number of people rising out of poverty.

The chapter has also examined the emerging evidence about the longer-run effects of food price changes on poverty. There are two important differences between the shorter- and longer-run effects. In the case of longer-run, wages have time to fully adjust to the change in prices, and producers have the opportunity to adjust their output levels and output mix to the change in prices. Here, the evidence suggests that higher food prices tend to lower poverty in most countries—frequently by substantial margins. It is important to note that the results considered here for both the short- and the long run are related to changes in food prices that are purely exogenous to developing countries. In developing countries, if a price increase is due, in whole or in part, to a decline in productivity, estimates of the effect on incomes will need to consider the direct adverse effect on incomes of the decline in productivity.

The concluding section of this chapter has reviewed the policy options for developing countries when dealing with the problem of food price volatility. As noted, the most commonly adopted response—insulating domestic markets against changes in world market prices—introduces a collective action problem. This problem renders domestic market insulation ineffective in stabilizing most prices and in mitigating the adverse poverty effects of price surges. Complementing trade policy measures with storage measures alleviates, but does not solve, this collective action problem. It also poses a serious challenge in terms of management, cost, and sustainability. There is a strong case for first-best policies based on creating social safety nets at national level and also for efforts to diminish the collective action problem through agreements that restrain the extent of beggar-thy-neighbor policy responses.

References

Anderson K (ed) (2009) Distortions to agricultural incentives: a global perspective, 1955 to 2007. Palgrave Macmillan/World Bank, London/Washington, DC

Anderson K, Ivanic M, Martin W (2014) Food price spikes, price insulation, and poverty. In: Chavas J-P, Hummels D, Wright B (eds) The economics of food price volatility. University of Chicago Press for NBER, earlier version available as Policy Research Working Paper 6535, World Bank

Boyce J, Ravallion M (1991) A dynamic econometric model of agricultural wage determination in Bangladesh. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 53(4):361–376

Carletto C (2012) Presumed poorer until proven net-seller: measuring who wins and who loses from high food prices. Development Impact Blog, World Bank, 19 Sept 2012

Caves R, Jones R (1973) World trade and payments: an introduction. Little Brown, New York

de Hoyos R, Medvedev D (2011) Poverty effects of higher food prices: a global perspective. Rev Dev Econ 15(3):387–402

Deaton A (1989) Rice prices and income distribution in Thailand: a non-parametric analysis. Econ J 99(395):1–37

Ferreira F, Fruttero A, Leite P, Lucchetti L (2013) Rising food prices and household welfare: evidence from Brazil in 2008. J Agric Econ 64(1):151–176

Gautam M, Gouel C, Martin W (2014) Managing wheat price volatility in India. World Bank, Washington, DC (Unpublished draft)

Gouel C, Jean S (2014) Optimal food price stabilization in a small open developing country. Policy Research Working Paper 5943, World Bank, Washington, DC, forthcoming in Oxford Economic Papers

Headey D (2011) Was the global food crisis really a crisis? Simulations versus self-reporting. IFPRI Discussion Paper 01087, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Headey D (2014) Food prices and poverty reduction in the long run. In: IFPRI Discussion Paper 01331, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington DC

Headey D (2015) Urban wage behavior and food price inflation in Ethiopia, Mimeo, International Food Policy Research Institute

Headey D, Fan S (2010) Reflections on the global food crisis. Research Monograph 165, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Headey D, Nisrane F, Worku I, Dessa M, Seyoum Taffesse A (2012) Urban wage behavior during food price hikes: the case of Ethiopia, ESSP-II Working Paper No. 41, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Ethiopia

Ivanic M, Martin W (2008) Implications of higher global food prices for poverty in low-income countries. Agric Econ 39:405–416

Ivanic M, Martin W (2014a) Short- and long-run impacts of food price changes on poverty. Policy Research Working Paper 7011, World Bank, Washington DC

Ivanic M, Martin W (2014b) World food price rises and the poor 2006–12: a slow food price crisis? World Bank, Washington, DC (Unpublished draft)

Ivanic M, Martin W, Zaman H (2012) Estimating the short-run poverty impacts of the 2010 surge in food prices. World Dev 40(11):2302–2317

Jacoby (2013) Food prices, wages, and welfare in rural India. Policy Research Working Paper 6412, World Bank (forthcoming in Economic Inquiry)

Knudsen O, Nash J (1990) Domestic price stabilization schemes in developing countries. Econ Dev Cult Change 38(3):539–558

Lasco C, Myers R, Bernsten R (2008) Dynamics of rice prices and agricultural wages in the Philippines. Agric Econ 38:339–348

Martin W (1997) Measuring welfare changes with distortions. In: Francois J, Reinert K (eds) Applied methods for trade policy analysis: a handbook. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Martin W, Anderson K (2012) Export restrictions and price insulation during commodity price booms. Am J Agric Econ 94(2):422–427

Nicita A, Olarreaga M, Porto G (2014) Pro-poor trade policy in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Int Econ 92(2):252–265

Porto G (2005) Informal export barriers and poverty. J Int Econ 66:447–470

Ravallion M (1990) Rural welfare effects of food price changes under induced wage rate responses: theory and evidence for Bangladesh. Oxf Econ Pap 42(3):574–585

Wodon Q, Zaman H (2010) Higher food prices in Sub-Saharan Africa: poverty impact and policy responses. World Bank Res Obs 25(1):157–176

Wright B (2014) Global biofuels: key to the puzzle of grain market behavior. J Econ Perspect 28(1):73–98

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Martin, W., Ivanic, M. (2016). Food Price Changes, Price Insulation, and Their Impacts on Global and Domestic Poverty. In: Kalkuhl, M., von Braun, J., Torero, M. (eds) Food Price Volatility and Its Implications for Food Security and Policy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28201-5_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28201-5_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-28199-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-28201-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)