Abstract

This chapter discusses a theme related to methodological settings, learning and knowledge production in the realm of futures studies and foresight. The author focuses on the synergy that comes from combining an entrepreneurial mindset and transdisciplinary research with organizational and personal knowledge management activities in the context of foresight initiatives and projects. Evolving ideas and concepts to develop research, which deals with the integration of entrepreneurship, foresight and knowledge management, have been put forward in several national-level initiatives, projects and higher education modules in Latvia (2003–2009).

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Knowledge Management

- Knowledge Production

- Strategic Thinking

- Transdisciplinary Research

- Methodological Setting

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

This chapter discusses a theme related to methodological settings, learning and knowledge production in the realm of futures studies and foresight. The author focuses on the synergy that comes from combining an entrepreneurial mindset and transdisciplinary research with organizational and personal knowledge management activities in the context of foresight initiatives and projects. Evolving ideas and concepts to develop research, which deals with the integration of entrepreneurship, foresight and knowledge management, have been put forward in several national-level initiatives, projects and higher education modules in Latvia (2003–2009).

Can we perceive already executed or new foresight projects as drivers for entrepreneurial and innovative thinking that enhance the capabilities of research organizations? The answer might be ‘yes’ in one case and ‘no’ in the others. And what would we say about foresight and knowledge management (KM) interrelations? Perhaps not very much for many reasons. In our world, KM has many faces, interpretations and applications, and this field of enquiry deserves a particular place in the foresight area.

This chapter describes a number of interrelated elements and processes and tracks how they develop synergies for foresight. The study is structured in the following sections.

Section 10.2 informs on the knowledge base of this chapter. The first steps are concerned with explaining the synergy, providing the definitions applied and explaining their value for our research and projects. Section 10.3 looks at the work of foresight organizations (teams) and presents the author’s reflections on their achievements and failures, considering the synergy issues of Latvian foresight activities, as well as experience obtained in European projects. Section 10.4 refers to entrepreneurial KM activities integrated into foresight research and presents a KM case that we can design for the task concerned. The outcomes of these endeavours are identified at the national level. The conclusions to this chapter, in Sect. 10.5, contain thoughts based on the identified challenges concerning possible ways to work more effectively and efficiently in the proposed direction.

2 Definitions to Enlighten What Is in the Task Concerned

2.1 The Knowledge Base for This Chapter

The exploratory studies for this chapter, its theoretical and problem-solving issues, are mostly related to the project ‘Latvia towards Knowledge Societies of Europe: new options for entrepreneurship and employment achieving the goals of the Lisbon strategy’ (the LNELS project) (Puga 2007). This initiative, intended for the period 2003–2010, was launched by the Forward Studies Unit, an independent research body located in Riga. The aim and main task for this project is to explore theoretical issues and offer conceptual and practical ways of how to promote entrepreneurship in R&D activities by finding new options for knowledge workers to gain employment related to forward-looking intelligence, including foresight on technology and social issues.

The core problem of the LNELS initiative was how to promote the understanding/incremental recognition of the futures and foresight area as a particular field of inquiry in Latvia and some other countries. Therefore, we need to approach both individual mindsets and organizational structures in political, academic, business and other areas.

In 2004–2009, some basic ideas and frameworks of the LNELS project were transferred to foresight activities and projects conducted by the Latvian Technological Centre, the Latvian Academy of Sciences, the Latvian Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, the Riga Technical University and the University of Latvia and to students then at the School of Business Administration Turiba in Riga (Puga 2007; Puga 2008). The LNELS researchers have grounded their research on methodological studies, projects and exercises performed in the EU and other countries in recent decades, and they themselves have contributed inputs to more than ten European and regional foresights in the last 5 years (e.g. Knowledge Society Foresight, the European Foresight Monitoring Network, FISTERA, ForeIntegra-RI) (Puga 2007, 2008).

2.2 How to Initiate Synergy

The LNELS approach proposes that in launching a foresight project/exercise, many introductory and explanatory activities should be set up in order to improve the understanding of the project team and stakeholders about the particularities of the foresight study concerned.

The perception of the intangibles and research processes in which the project team and stakeholders would/should be engaged, of activities of different kinds and their outputs and deliverables and of the synergetic potential of the people involved can all be important in shaping the foresight team’s philosophy, research culture and particular ways of knowledge production. European foresight initiatives and exercises and the European foresight area itself are ‘young children’ unknown or obscure for many people in S&T policymaking, academia and other groups and communities in European countries.

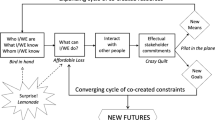

Knowledge on transdisciplinarity and mode 2 of knowledge production (see definitions in Sect. 10.2.3) can help the foresight organization to adapt more easily to the multidimensional scope of knowledge work (see Figs. 10.1 and 10.2 in this section, and Fig. 10.3 in Sect. 10.3.1). Such work requires willingness and entrepreneurial efforts leading to evolving strategic thinking for new products and applications and also to the self-assurance of those people who might try to interpret their own individual foresight in the project team activities.

To begin with, it is also significant to consider selected examples for the development of a better understanding of different parts of the strategy process: strategic thinking and foresight as its basic elements, strategic development or decision making, strategic planning and ultimately strategic implementation (Voros 2003).

In the case of success, a variety of ideas, concepts and discussed examples of transdisciplinarity and mode 2 of knowledge production interacting with individuals’ tacit and explicit knowledge evolve for the tasks concerned, and this can also trigger and increase the entrepreneurial abilities of the team members and their strategic thinking, while setting up step by step a future-friendly mental and physical environment for futures research and knowledge management.

In such a way, synergy can be created for futures research processes. This can mitigate the inevitable cognitive and organizational gaps between what we know and what we should learn and perform in dealing with futures.

Opposite to this approach might be the attitude and activities of some individuals, developments in the foresight organization characterized by terms like ‘unreadiness’, ‘unsociability’, ‘apathy’ and ‘conflict’.

People’s mindsets, endeavours and capabilities motivated towards outputs and deliverables, involved in individual and organizational knowledge production using technological options and intertwined with individual and organizational values are often challenged and specifically ‘addressed’ by the foresight to which they contribute.

2.3 Definitions for the Foresight Organization’s Work

The author argues that a good understanding of the definitions (selected by the team or individual) that are the main building blocks for knowledge work and provide a platform for the task concerned can be one of the key issues of success when dealing with futures and KM activities. The aim is to enter in depth into the complexity of definitions and coherently integrate evolving outputs: that is, to enhance and orientate our mental work in an entrepreneurial direction.

In adopting this approach to futures studies, the LNELS project team selected the following definitions and explanations which seemed to be most appropriate for reasons of both cognitive and practical application:

Foresight – thinking, debating and shaping the future – can increase strategic intelligence capabilities for policies, industry and innovation, research, education, etc. (Busquin 2002). ‘Foresight is a systematic, participatory process, collecting future intelligence and building medium- to long-term visions, aimed at influencing present-day decisions and mobilizing joint actions. It helps in making choices in complex situations by discussing alternative options, bringing together different communities with their complementary knowledge and experience’ (UNIDO 2007).

Entrepreneurship – ‘the mindset and process to create and develop economic activity by blending risk-taking, creativity and/or innovation with sound management, within a new or an existing organisation’ (European Commission 2003).

Mode 2 of knowledge production (a set of cognitive, research and social practices – ideas, methods, values, norms, etc.) is characterized by:

-

Knowledge produced in the context of application

-

Transdisciplinarity

-

Heterogeneity and organizational diversity

-

Enhanced social accountability

-

More broadly based system of quality control (Gibbons 1997)

Transdisciplinarity – Enables the development of a distinct but evolving framework to guide problem-solving efforts. This is generated and sustained in the context of application and not developed first and then applied to that context later by a different group of practitioners.

Transdisciplinary knowledge develops its own distinct theoretical structures, research methods and modes of practice, though they may not be located on the prevailing disciplinary map.

The diffusion of the results is initially accomplished in the process of their production. Subsequent diffusion occurs primarily when the original practitioners move to new problem contexts, rather than through reporting results in professional journals or at conferences. Communication links are maintained partly through formal and partly through informal channels.

Transdisciplinarity is dynamic. It is problem-solving capability on the move. A particular solution can become the cognitive site from which further advances can be made, but where this knowledge will be used next and how it will develop are as difficult to predict as are the possible applications that might arise from discipline-based research (Gibbons 1997). ‘Rather, it is in the context of application that new lines of intellectual endeavour emerge and develop, so that one set of conversations and instrumentation in the context of application leads to another, and another, again and again’ (Nowotny 2003).

Knowledge worker – ‘An individual whose primary contribution is through the knowledge that they possess or process. This contrasts with workers whose work is predominantly manual or following highly specified procedures with little scope for individual thought’ (David Skyrme Associates 2008).

Organizational knowledge management (OKM) – Knowledge management is the name given to the set of systematic and disciplined actions that an organization can take to obtain the greatest value from the knowledge available to it. ‘Knowledge’ in this context includes both the experience and understanding of the people in the organization and the information artefacts, such as documents and reports, available within the organization and in the world outside. Effective knowledge management typically requires an appropriate combination of organizational, social and managerial initiatives along with, in many cases, deployment of appropriate technology (Marwick 2001).

Personal knowledge management (PKM) – ‘A set of concepts, disciplines and tools for organizing often previously unstructured knowledge, to help individuals take responsibility for what they know and who they know’ (European Committee for Standardization 2004b). ‘KM only makes sense if knowledge is important for the job at hand and when the individual possesses and/or needs knowledge to reach his or her objectives’ (European Committee for Standardization 2004a).

The LNELS approach aims at horizontal application and adaptation of the designed and tested frameworks and examples of its teams’ activities that have roots in processes defined above. These cases are intended for a broad spectrum of applicants in different areas of knowledge production about futures.

3 The Foresight Organization and Its Interactions to Stimulate Mindsets and Obtain Knowledge

3.1 The Project Team in the World of Knowledge

A general model of the foresight project organization (FO) can be perceived to be adaptable to a wide variety of applications to design, plan and manage new and ongoing interactions. In this case, organization is an evolving set of the processes involved in handling futures-related knowledge and managing knowledge work by a group of people (e.g. the LNELS team) who have a shared purpose and interests. The FO and its members interact with organizations and individuals in the world outside and apply a combination of organizational, social and managerial actions to reach research targets using appropriate technologies. They should interact with the project stakeholders throughout the entire project time and, what is important, also after the job is completed.

We can consider FO as a mechanism which ensures the relationship between the project researchers and their environment, people and organizations and bodies of knowledge. In this context, one should think about KM issues.

In global knowledge exchange and trade, the FO actions for the task concerned can be twofold and interrelated. They should support:

-

A set of organizational, social, managerial and technological processes which ensure innovative ways and appropriate methods for knowledge production and execution of the project as a whole

-

The foresight process itself – to generate ideas, use methods and work with alternative futures, and manage the foresight knowledge production which results in the project deliverables

Following transdisciplinarity, LNELS applies the ideas, conceptual findings and results of each of its phases to new tasks, and KM activities contribute to the incremental progress towards the goals. The combination of integrative, exploratory, interactive, participative, experimental and skills-building processes has been developed by applying and rethinking knowledge and experience gained from European and other international projects and workshops and knowledge artefacts (Puga 2007).

The richness of the LNELS expanding knowledge repository, the application of the explicit knowledge for increasing understanding about the methodology and practice of foresight programmes and exercises by the LNELS team and the use of possibilities to obtain experience and new impressions by working together with the leading foresight specialists of EU and other countries in both real and virtual environment – all these factors, coupled with knowledge-intensive work – were essential to ensure a sustained LNELS process. Entrepreneurship was the key to exploit the new opportunities the researchers began to develop for themselves and others.

Having commitment | Supporting | Learning | Exploring |

Networking | Performing knowledge, building capabilities, producing deliverables | Conversing, having dialogue | |

Collaborating | Understanding | ||

Achieving objectives and purpose | Innovating | Changing | Searching |

In this case, values play an important role – to understand and promote foresight to be a knowledge domain like history, literature and management, and many intangible and other values have an impact on it.

3.2 Different Approaches to Foresight: Will Mode 1 or Mode 2 Be the Leader?

This section refers to five national-level projects and exercises related to foresight and supported by the Latvian Council of Science, the Latvian Academy of Sciences and the EU Structural Funds in 2003–2008. The first (the LNELS foresight organization) explored and translated into research activities a great deal of knowledge on KM topics. The LNELS outputs of 2004–2007 include a methodological framing for the practical application, enhancement and further development of KM approaches to foresight. The results indicate that understanding of KM terminology and processes enables the active participation of researchers in foresight projects at the national and the European level (Puga 2007, 2008).

We look at four projects that had a different approach than LNELS. The next FO comprised about 15 scientists and researchers, almost all of whom were from academia. They implemented two national-level projects dealing with agricultural and rural foresight.

Another research team worked on the elaboration of a conceptual module of the KM system for corporate foresight in SMEs. This organization included about ten researchers and young scientists mainly from a technical university.

Evidence for this was also collected from the teaching and learning processes of a Master’s studies module at the University of Latvia in 2008. In this course, futures methodology and synergy between foresight and knowledge management activities had been discussed for application in the natural sciences and in building capabilities to promote processes of sustainable development (Puga 2008).

The above-mentioned four projects were conducted (over the course of 1 or 2 years) by academic organizations. Those core teams consisted of top-level scientists and professors, and they mostly emphasized a disciplinary way of thinking and practices (what is termed as mode 1 of knowledge production) in both organizational and research activities. The teams tended to maintain well-known and routine ways of management while running foresight. The research methods and results were accepted by clients from government bodies. However, the projects have not attracted much attention from the scientific or business communities: for instance, to discuss the foresight methodology and consider the foresight role for R&D policy or societal issues. It is now difficult to find information on the application of the foresight projects. In Latvia, as in some other countries, S&T policy and research funding continue to operate predominantly within disciplinary constraints.

At the same time, research practices of foresight projects are associated with mode 2. Considering another domain of thought that challenges and often embarrasses a part of the academic world – KM – we also find it associated with mode 2 of knowledge production.

In the view of the author, possible ways to generate the synergy of entrepreneurial thinking, KM and foresight activities can be learned and discussed by the team members and, as far as possible, by individual stakeholders. That requires commitment from the project champions, team and other participants – to think out of the box, to be open to other mindsets and innovative ideas and to try to understand, analyse and synthesize those ideas – producing individually and collectively new knowledge for the following phases of the project and eventually for applications of the results that the public can freely evaluate and develop.

4 Entrepreneurship and KM Support to Develop Foresight at Different Levels

4.1 PKM for and in the FO

We need to address a great deal of intangibles and material elements, tools and assets to integrate entrepreneurship, knowledge management and foresight in order to develop a system of knowledge production in the FO. A case of personal knowledge management to promote individual foresight (IF) capabilities can be considered as a useful framework while performing the task concerned. How could such a case be mentally constructed and really shaped to become adapted to changing realities? Let us think about the following parts:

-

To understand the objectives and the goals of the foresight project/exercise, careful and often time-consuming knowledge work should be done. In their personal and organizational activities, individuals should be motivated and interested in enhancing their ownership of knowledge in order to reach new objectives by orienting their work in an entrepreneurial direction.

-

Knowledge means both assets and processes that benefit from and give benefit to IF. New assets are produced and accumulated during transdisciplinary work within the FO. Processes of socialization, externalization, combination and internalization of knowledge are in progress. Sets of ideas, concepts, approaches, methodologies and frameworks are evolving for the task concerned and far beyond it.

-

Working with the FO and people in the outside world, the knowledge worker can identify needs and critical skills deficiencies. This process leads him/her to a better understanding and acquisition of new/improved skills in some disciplines and research areas, which are to be integrated in producing knowledge and applied in transdisciplinary work.

-

A part of the framework of PKM for IF relates to tools for foresight research and knowledge management activities. We need both instruments and skills to search for and capture information, to create, organize and share knowledge. This leads to an evolving virtual workplace available around the clock from ‘anywhere in the world’. To ensure access to information artefacts and knowledge owners, a set of emails, software programs, online dictionaries, social media, communications and other tools are applied for the individual and FO work. Databases and knowledge repositories support researchers in all phases of the foresight process (Puga 2007).

4.2 The Improved Dialogue Results in the Dissemination and Recognition of Foresight at the National Level

In 2006–2008, some methodological settings, methods and techniques through dialogues and the dissemination of international experience and LNELS activities were transferred to, and later implemented in, several projects supported by the Latvian Council of Sciences, the Latvian Academy of Sciences and ministries and universities in Riga. Top-level policymakers from the Ministry of Education and Science and the Ministry of Agriculture, as well as two academies, signed an agreement on the cooperation within the network of foresight specialists and practitioners for Latvian agricultural research (Zinātnes Vēstnesis 2007). In 2007, foresight was recognized as a new research area by the Latvian Academy of Sciences. In that year, the Terminology Commission of the Latvian Academy of Sciences also made a decision to introduce new terms that apply to this discipline (Latvijas Zinātnu akadēmijas gadagrāmata 2008).

4.3 To Integrate Entrepreneurial Activities, Strategic Thinking and KM with Learning New Transdisciplinarities (Options of Horizontal Application)

As illustrated in Figs. 10.1 and 10.2, frameworks and processes that stem from and develop further synergy of entrepreneurship, knowledge management and futures research have been applied during the teaching and learning of the course on lobbying (interest representation) techniques of the School of Business Administration Turiba in Riga, Latvia. This course is a module of a programme to obtain a professional qualification and the Master’s degree in public relations. Interest representation, similarly to KM and foresight, is a relatively new area for both education and research in some European universities.

All of the following support the entrepreneurial endeavour and students’ ways of obtaining knowledge on and practical skills associated with lobbying topics: the introduction to transdisciplinary work and shift into fields of knowledge that are important for understanding the complexity of the lobbying area; the description of this area as very necessary for a society in which everyone individually and/or through the organization/s contacts (business, R&D, education, non-profit/NGO, local and other communities) with parliamentary or government institutions might be involved; and insights into lobbying cases with a focus on strategy development and its aspect – strategic thinking that plays a significant role for lobbying.

The author’s experience as a lobbying teacher indicates that cases of PKM are useful and applicable for lecturers and may be also suggested to students. During the lobbying course, a virtual learning and knowledge-sharing space (website of LTehno group on SCRIBD) was developed by more than 30 Master’s students organized in a knowledge community (LTehno group 2009).

In a future-friendly environment, the majority of students will have shown commitment that leads to higher levels of knowledge and skills when studying the course subjects. Members of the group have collaborated, networked, searched, explored, supported each other and step by step contributed with inputs to develop a critical mass for this new area of knowledge in Latvia.

How to deal with futures and innovate in order to change citizens’ attitude to be at ease with lobbying rather than to be hostile to it – these are important issues that students have tried to evaluate and discuss. They produced individual and team outputs resulting in deliverables, for instance, presentations placed in the team’s virtual space; shared knowledge with people outside the student group at work, their family; and designed lobbying cases for organizations and others.

The LNELS project and its research on the elaboration of specific frameworks and approaches, their application and lessons about relationships based on knowledge, trust and commitment point to the usefulness of theoretical work for developing the synergy of entrepreneurship, KM and foresight. The author of this chapter proposes to continue research and extend its potential for adaptation (for different foresight tasks, institutions, areas).

5 About Consequences

Discussing, researching and evaluating ideas/good practice/obstacles for synergies of entrepreneurship, foresight and knowledge management can be a constructive and perhaps particularly fruitful way to attract the attention of people to each of these domains and to their natural unity.

The futures activities and methodological framing described support the opinion that entrepreneurship can be promoted by creating, converting and sharing knowledge in a favourable mental and physical environment and by approaching in skilled way knowledge sources in and outside the organization.

People live in communities – self-organizing and adapting to a previously established environment and to economic, political and ideological meta-frameworks. National and supranational powers and interconnected and overlapping communities have their own ‘systems of values’. The author believes that ‘knowledge’ and ‘intelligence’ are not prioritized enough in existing and self-developing ‘systems of values’ across the world. Self-organizing change in companies, research organizations and communities, supported by a deeper approach to knowledge for foresight culture, remains a challenging theme for European research.

References

Busquin, P. (2002). The foresight dimension of the European research area. In The role of foresight in the selection of research policy priorities. Conference Proceedings, EC, JRC-IPTS, pp. 19–23.

David Skyrme Associates (2008). http://www.skyrme.com/resource/glossary.htm accessed on 30 sep 2012

European Commission (2003) Green Paper: Entrepreneurship in Europe, Brussels, Document based on COM 27 final.

European Committee for Standardization. (2004a). European guide to good practice in knowledge management – Part 1: Knowledge management framework. Brussels: CEN.

European Committee for Standardization. (2004b). European guide to good practice in knowledge management – Part 5: KM terminology. Brussels: CEN.

Gibbons, M. (1997). What kind of University? Research and Teaching in the 21st Century, 1997 Beanland Lecture, Melbourne: Victoria University of Technology.

Latvijas Zinātņu akadēmijas gadagrāmata (2008). Riga, 199.lpp.

LTehno group (2009). Lobbying technologies. Course for the Masters Program in PR, BAT. http://www.scribd.com/group/70099-ltehno Accessed on 18 April 2012.

Marwick, A. (2001). Knowledge management technology. IBM Systems Journal, 40(4), 814–830.

Nowotny, H. (2003). The potential of transdisciplinarity. Rethinking interdisciplinarity. http://w7.ens-lyon.fr/amrieu/IMG/pdf/Nowotny_Interdisciplinarity_5-08.pdf Accessed on 30 sep 2012.

Puga, A. (2007). A Latvian experience addressing issues of the foresight innovation. International Journal of Foresight and Innovation Policy, 3(4), 369–387. accessed on 30 sep 2012.

Puga, A. (2008, April 23–25). Pursuing innovation: The foresight issues in Latvian universities. In TII 2008 annual conference, Valencia. http://www.tii.org Accessed on 30 sep 2012.

UNIDO (2007, September 27–29). Technology Foresight Summit 2007, Documentation, Budapest, p. viii.

Voros, J. (2003). A generic foresight process framework. Foresight, 5(3), 10–21.

Zinātnes Vēstnesis (2007). Scientific Bulletin: 3, 5 February, Association of Latvian Scientists, Riga, Latvia. http://www.lza.lv/ZV/zv070300.htm Accessed on 30 sep 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Puga, A. (2013). Will Entrepreneurship, Knowledge Management and Foresight Emerge in a System?. In: Giaoutzi, M., Sapio, B. (eds) Recent Developments in Foresight Methodologies. Complex Networks and Dynamic Systems, vol 1. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5215-7_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5215-7_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-5214-0

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-5215-7

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)