Abstract

A high-resolution geoid model covering the four main islands of Japan has been developed on a 1 by 1.5 arc-minute grid from EGM2008 and terrestrial gravity data. The Stokes-Helmert scheme in a modified form is applied for the determination of the geoid using an empirically-determined optimal spherical cap, and Kriging is used for gridding the residual gravity anomalies. In comparison with the previous geoid model for Japan (JGEOID2008), there is a slight improvement in the standard deviation from ±8.44 cm to ±8.29 cm. It is noted that although the determined gravimetric geoid model represents the geoid over Japan fairly well, there is still a need for more gravity data especially in the northern parts of Japan.

Similar content being viewed by others

1. Introduction

One of the most extensively used satellite positioning systems in Earth sciences is the Global Positioning System (GPS). It is a fast and efficient way of determining positions based on the World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS84). It measures ellipsoidal heights h above the WGS84 reference ellipsoid. However, orthometric heights, H, are the functional heights for mapping, engineering works, navigation and other geophysical applications. The orthometric heights are normally obtained through spirit levelling, which is a very tedious and expensive process. To exploit the capabilities of GPS for height purposes, the geoid should be determined in an area. The geoid is a closed and continuous level surface, which extends inside the solid body of the Earth and is best suited as a reference surface for a rigorous orthometric height system.

Geoid determination in Japan has been studied by several authors (e.g. Ganeko, 1976; Kuroishi, 1995, 2001a, b, 2009; Fukuda et al., 1997; Kuroda et al., 1997; Kuroishi and Denker, 2001; Kuroishi et al., 2002; Kuroishi and Keller, 2005). Early geoid determinations were achieved using astrogeodetic techniques (e.g. Ganeko, 1976). With the development of fairly reliable global geopotential models (GGMs) and the availability of regional gravity data, Japanese geoid determination in the recent past has been achieved by gravimetric techniques.

The main GGMs that have been used in Japan for geoid determination are OSU91A (Rapp et al., 1991) and EGM96 (Lemoine et al., 1997), with the latter performing better over Japan. However, Kuroishi (2009) developed JGEOID2008 from a GRACE-based GGM, GGM02C (Tapley et al., 2005) combined with EGM96 (i.e. GGM02C/EGM96), terrestrial gravity measurements and an altimetry-derived marine gravity model, KMS2002 (Andersen et al., 2005). The earlier geoid models are JGEOID93 (Kuroishi, 1995), JGEOID98 (Kuroishi, 2001a), JGEOID2000 (Kuroishi, 2001b) and JGEOID2004 (Kuroishi and Keller, 2005).

The use of the Earth Gravitational Model 2008 (EGM2008), combined with local terrestrial gravity data, is considered for geoid determination over Japan in this study. EGM2008 is complete to spherical harmonic degree and order 2,159, and contains additional coefficients extending to degree 2,190 and order 2,159 (Pavlis et al., 2008). In addition, it is supplied with a conversion model complete to degree and order 2,160 for converting height anomalies to geoid undulations (Pavlis et al., 2008).

A comparison between JGEOID2008 and EGM2008 implied geoid undulations shows that the former is superior in the area of study (e.g. Kuroishi, 2009). However, the performance of EGM2008, combined with local terrestrial gravity data, has not been investigated in the same area. The ship-track gravity data and satellite altimeter-derived marine gravity anomalies in coastal areas have been excluded in this study because of the use of the high-resolution geopotential model (EGM2008). Furthermore, the interest of this study is limited to the land areas. A detailed description of data sets, including datum transformations where necessary, is presented in this paper. Gravity reductions and gridding using the Kriging technique are discussed. The paper concludes with a validation of the derived geoid model with GPS/levelling geoid undulations.

2. Geodetic Datum and Data Description

The Japanese horizontal geodetic datum has evolved since 1892 to the present. The initial horizontal datum (Tokyo Datum) was established in 1892 with its origin at Azabu in Tokyo and adjusted on the Bessel 1841 reference ellipsoid. The Tokyo Datum was in use until 31st March, 2002, when it was replaced by the current Japanese Geodetic Datum 2000 (JGD2000) on 1 April, 2002 (e.g. Matsumura et al., 2004). The JGD2000 was realized through space-based observation techniques and network adjustment carried out on GRS80 (Moritz, 1980) and connected to the ITRF94 (Boucher et al., 1996).

The establishment of the Japanese vertical datum can be traced to the levelling survey carried out by the Army Land Survey in 1883 (Imakiire and Hakoiwa, 2004). Initially, the normal-orthometric height system was used in Japan before the conversion to the current Helmert orthometric height system obtained by incorporating measured gravity data (e.g. Imakiire and Hakoiwa, 2004).

The bulk of the gravity data was obtained from the database developed by Nagoya University and other organizations covering the south western part of Japan (e.g. Shichi and Yamamoto, 2001a, b). The database consists of gravity measurements made between 1955 and 2001. Another set of gravity data mainly along the main levelling network covering the four main islands (Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu and Shikoku) was provided by the Geographic Survey Institute (GSI)—the current Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. This set of data was observed between 1910 and 1999. In total there are 98,670 observed gravity data in the study area.

In terms of coverage, the northern part of Japan (above latitude 37°N) is sparsely covered, while the southern part is densely covered, by gravity data. However, it is important to note that the bulk of the gravity data was collected for purposes other than geoid modelling. This can be seen from the various organizations involved in the data collection, the distribution of gravity stations and the approximation techniques used especially for the horizontal and vertical positions. Some gravity observations were carried out on benchmarks and triangulation points, but the heights of a large number of gravity points were interpolated from contour maps or approximated using the local sea surface. Most of the gravity observations are in low areas (<500 m) with 85,069 data points (86%), followed by the mid-elevation areas (500 m–1,000 m) with 10,791 data points (11%), while high-elevation areas (> 1,000 m) have 2,810 data points (3%).

The Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) on the Tokyo Datum covering the four main islands were prepared in 1999 by GSI. The Hokkaido area is covered by a 250-m DEM while the other three main islands (Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu) are covered by a 50-m DEM. It is worth noting that both the DEMs and gravity data coordinates are based on the Tokyo Datum. Hence, a datum transformation from Tokyo datum to JGD2000 was carried out for DEMs and gravity data. Details on the transformation parameters between Tokyo Datum and JGD2000 can be found in Tobita (2001). The gravity data are referred to the Japanese Gravity Standardization Net 1996 (JGSN96, Yamaguchi et al., 1997; Shichi and Yamamoto, 2001a, b).

3. Gravity Reductions and Gridding

The method of downward continuation of observed gravity on the topographical surface to the geoid plays a central role in precise geoid determination. Stokes’s formula for gravimetric geoid determination requires that there be no masses outside the geoid and the gravity anomaly be referred to the geoid. One way of satisfying these requirements is to use Helmert’s second condensation technique (Heiskanen and Moritz, 1967, sections 3–7, 4-3; Vaníček and Kleusberg, 1987; Sideris and Forsberg, 1991). Downward/upward continuation of the observed gravity to the geoid by Helmert’s second condensation technique is consistent with Stokes’s formula for gravimetric geoid determination (e.g. Martinec et al., 1993).

According to Helmert’s second condensation technique, the gravity anomaly on the geoid (Δ g o) can be computed (Martinec et al., 1993, based on investigations of Sideris and Forsberg, 1991; Vaníček and Kleusberg, 1987; Wang and Rapp, 1990) as,

where ΔgFA is the free-air gravity anomaly, A

P

is the attraction of the topographical masses above the geoid at the observation point,  is the attraction of the condensed topography at a point P on the topographical surface, g1 represents the harmonic downward continuation of the anomalous gravitation from the observation point to the geoid, and δs is the secondary indirect terrain effect on gravity. The determination of the term g1 requires that the gravity anomalies be continued from the topographical surface to the geoid. This procedure can be avoided by assuming that the free-air gravity anomaly is linearly dependent on the elevation of the topography (Pellinen, 1962; Moritz, 1966).

is the attraction of the condensed topography at a point P on the topographical surface, g1 represents the harmonic downward continuation of the anomalous gravitation from the observation point to the geoid, and δs is the secondary indirect terrain effect on gravity. The determination of the term g1 requires that the gravity anomalies be continued from the topographical surface to the geoid. This procedure can be avoided by assuming that the free-air gravity anomaly is linearly dependent on the elevation of the topography (Pellinen, 1962; Moritz, 1966).

Using this assumption, Martinec et al. (1993) have shown that,

where C is the gravimetric terrain correction given in planar approximation as (Moritz, 1980),

where G is the Newtonian gravitational constant, ρ is the constant topographic density, H P is the orthometric height of the computation point, H is the height of the running point, σ is the surface integration element, and lo is the horizontal distance between the computation point and the running point. Hence, the reduced gravity anomaly on the geoid is given as:

The free-air gravity anomaly used in this study is computed as,

where gob is the observed gravity, δgfa is the second-order free-air reduction (Heiskanen and Moritz, 1967), δgac is the atmospheric correction (Wichiencharoen, 1982a), and γ is the normal gravity on the reference ellipsoid. The secondary indirect terrain effect on gravity is given as (Vaníček et al., 1999),

where Rψ is a planar approximation of the horizontal distance lo between the computation and the running points. Although this correction was included, its magnitude ranges only between -64 µGal and 13 µGal in the area of study. The indirect effect on the geoid due to gravity reduction was evaluated using the planar formula given as (Wichiencharoen, 1982b),

The residual gravity anomaly (Δgr) is then given as,

where ΔgGGM is the gravity anomaly obtained from the full expansion of EGM2008 (2,190 × 2,159).

A consistency procedure was applied to the residual gravity anomalies to select gravity data for geoid determination. First, all residual gravity anomalies outside 2SD about the mean are removed, where SD is the standard deviation of the observations. The second consideration is the spatial consistency between neighbouring points. In this phase, the residual gravity anomaly at each point is estimated in a cross-validation sense (using only gravity anomalies of neighbouring points). The standard deviation of the differences between the estimated and observed values for all the points is computed. A point is removed if the difference between the estimated and observed residual gravity anomalies is more than 3SD. However, care is taken in areas with less data coverage.

The statistics of gravity anomalies are given in Table 1, while Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the selected gravity data (57,021) for geoid determination. The slightly higher mean of the selected residual gravity anomalies is due to the removal of most of the negative residual gravity anomalies under the mountains because of inconsistency with the residual gravity anomalies in the relatively low areas.

As already mentioned, the gravity data used in this study was observed from 1910 to 2001 by various organizations, probably with varying accuracies, for purposes other than geoid modelling. Heights of a large number of gravity points were interpolated from contour maps or approximated using the local sea surface. Also, Japan is an area of constant crustal deformations. When such data (in the area described) is compared with the more recent highresolution GGM (EGM2008), and spatial consistency is applied in a cross-validation sense, then the removal of a large number of gravity data may not be so strange. However, a rigorous assessment of the Japanese gravity data may be necessary in the future.

The gridding of the residual gravity anomalies was accomplished by the Kriging technique (Krige, 1951) on a 1 × 1.5 minute grid. Kriging is a geo-statistical technique used for interpolating unknown values of a variable at unsampled points using measured values at the observation points. For the interpolation of residual gravity anomalies, we can write a Kriging estimator as,

where  is the estimated residual gravity anomaly, λ

i

is the Kriging weight, and n is the number of observations. The weight is determined in such a way that the Kriging estimator is an optimal estimator in the sense of being unbiased and having minimum estimation variance (Olea, 1974).

is the estimated residual gravity anomaly, λ

i

is the Kriging weight, and n is the number of observations. The weight is determined in such a way that the Kriging estimator is an optimal estimator in the sense of being unbiased and having minimum estimation variance (Olea, 1974).

The practical application of Kriging starts from the verification of data features, mainly spatial dependency, stationarity and distribution. However, it is worth noting that like any other statistical analysis technique, the obvious outliers must be removed and known systematic errors accounted for before any meaningful analysis and interpretation, including interpolation, can be achieved from a set of data. In Kriging, the spatial dependency is modelled using a semivariogram given by,

where ŷ (h) is the semivariogram at a distance h, n

h

is the number of points in that distance class,  is the residual gravity anomaly at location i, and

is the residual gravity anomaly at location i, and  is the residual gravity anomaly at location j.

is the residual gravity anomaly at location j.

The implementation of Eq. (10) is easily done if the empirical semivariogram is estimated by a model. There are various models for semivariogram representation. However, exponential, Gaussian and spherical models are in common use. The choice of the model depends on the data structure; hence the use of an exponential model in this work. It is expressed as,

where θpsl is the partial sill which refers to the amount of variation in the process that is assumed to generate the data, Cngt is the nugget effect defined as a discontinuity at the origin caused by measurement and locational errors, and α is the range representing the distance beyond which there is no significant dependence, similar to the correlation length in least-squares collocation (LSC).

The choice of the Kriging technique for gridding in the area of study was based on an empirical evaluation of three techniques; Kriging, LSC and Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW). It should be noted that there are several other methods such as: polynomial fitting, continuous curvature splines in tension, the finite element method, and the multi-quadratic interpolation function, among others that were not tested in this study.

A cross-validation technique was applied using data in Hokkaido. Five test points, evenly distributed over the island were selected taking height variations into consideration. The test points were excluded in the evaluation of accuracy parameters (correlation length, variance, semivariogram, partial sill, nugget effect and range) in LSC and Kriging. They were also excluded in the IDW technique. The differences between residual gravity anomalies at the test points and the predicted values are given in Table 2, while Fig. 2 shows the distribution of gravity data and test points in the Hokkaido area.

From the basic statistics in Table 2, it can be seen that the Kriging technique performs slightly better than LSC and IDW. However, there is no significant difference in the predicted values considering the accuracy of the gravity data (≈1 mGal). We observe that although LSC may be the preferred technique for data combination including parameter estimation in geodesy, Kriging is relatively less labour intensive, fast and works fairly well. Therefore, Kriging was applied in the interpolation of residual gravity anomalies over the whole area of study.

4. Geoid Determination

Stokes’s concept of geoid determination was adopted in this study. Stokes (1849) published a formula for the disturbing potential on the surface of the geoid. Considering Bruns’s formula, Stokes’s integral formula for geoid determination is given as (Stokes, 1849; Heiskanen and Moritz, 1967),

where N is the geoid undulation, ψ is the spherical distance between the running and the computation points, R is the mean radius of the Earth, and S(ψ) is the Stokes’s kernel.

The Stokes’s formula, in a strict sense, requires that continuous gravity data be available, and be used, over the entire Earth. This condition is not satisfied currently, hence a remove-compute-restore procedure is normally considered for geoid determination. In this approach, a GGM provides the long-wavelength geoid undulations, a modified Stokes’s formula provides the medium-wavelength components, and the indirect effects of the topography provide the short-wavelength components. A modified Stokes’s kernel proposed by Meissl (1971) was used. Hence, the expanded modified Stokes’s formula excluding the ellipsoidal effect is given as,

where NGGM is the geoid undulation obtained from EGM2008 (2,190 × 2,159) after applying the zero-degree term, SME = S(ψ) − S(ψo) is Meissl’s modified kernel, and ε N is the truncation error, i.e. the geoid height information missing from gravity data outside the computation region (σ − σo). The second term in Eq. (13) includes the effect of the innermost zone which is computed separately because Stokes’s kernel becomes infinite at the computation point.

For a practical evaluation, the truncation error ε N can usually be ignored when using a high-degree GGM with the modified spheroidal Stokes’s integral (Amos and Featherstone, 2003). Although the use of a modified kernel reduces the truncation errors, there is no known optimal spherical distance (ψo) that can be used in all regions. Therefore, there is a need to evaluate the optimal spherical distance based on the regional data sets.

The optimal spherical distance was evaluated empirically by comparing gravimetric and GPS/levelling geoid undulations at spherical distances ranging from 18 km to 72 km. The comparisons were made at all the 816 GPS/levelling points and the standard deviation was computed for each spherical distance at an interval of 18 km. The following is a summary of the comparisons; 18(±8.49), 36(±8.29), 54(±8.37), 72(±8.46), where the numbers outside the brackets represent spherical distances in km, and the bracketed ones are the corresponding standard deviations in cm.

A spherical cap-size of 36 km was adopted for the computations in this study because it gives the smallest standard deviation compared to other distances. It may be interesting to determine the performance of other kernel modifications (e.g. Wong and Gore, 1969; Vaníček and Kleusberg, 1987; Featherstone et al., 1998) in the determination of geoid undulations over Japan.

5. Results and Discussion

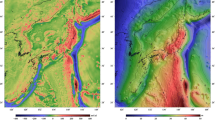

The residual geoid over the four main Japanese islands is given in Fig. 3 while the high-resolution geoid is shown in Fig. 4. To compare the gravimetric and the geometric geoid undulations, the levelled heights (mean-tide height system) are converted into the tide-free height system using the models proposed by Ekman (1989). This conversion makes the spirit-levelled heights compatible with the ellipsoidal heights obtained by GPS. The comparisons are carried out over the whole area using 816 GPS/levelling points, and for each island, except Honshu which is divided into three parts because of its size and geometry. Table 3 gives the statistics of the comparisons while Fig. 5 shows the distribution of the GPS/levelling stations over the four main islands.

The West Honshu area has the smallest standard deviation between the gravimetric and GPS/levelling geoid undulations, while Shikoku has the largest standard deviation, as shown in Table 3. Central Honshu is a mountainous area where most of the residual gravity anomalies are inconsistent with the surrounding low areas. The north eastern part of this area is sparsely covered by gravity data. However, the situation in Shikoku is rather challenging because it is of moderate elevation and moderately covered by gravity data. Although some inconsistent data from this area were removed, we cannot rule out the possible errors in the gravimetric geoid due to the exclusion of marine gravity data in the surrounding ocean areas, and the effect of crustal deformation on both gravity and levelling data.

In comparison with the previous geoid model for Japan (JGEOID2008) at 816 GPS/levelling points, there is a slight improvement in the standard deviation from ±8.44 cm to ±8.29 cm. After a planar fit (azimuth = 40.6° and tilt = 0.09 ppm), the standard deviation reduces to ±5.81 cm. A similar comparison using only EGM2008 implied geoid undulations give a mean value of –21.72 cm and a standard deviation of ±8.88 cm (e.g. Kuroishi, 2009). It is observed that EGM2008 represents the geoid over Japan relatively better than the previous GGMs.

The heights of the GPS/levelling points range between 0.3 m to 1,672.7 m with only one point above 1,000 m. Although most of the gravity anomalies in the mountainous areas were removed because of the inconsistency with the gravity anomalies of the relatively low areas, the gravimetric geoid obtained covers the whole range of the main levelling network in Japan.

It is observed that the standard deviation, though improved is still large. This may be attributed to measurement errors in the data sets and the exclusion of marine gravity data. The effect of crustal deformation and the possibility of omission and commission errors in the EGM2008 cannot be ignored. The comparison between gravimetric and GPS/levelling geoid undulations is based on the assumption that both the ellipsoidal and orthometric heights are correct and consistent with the theoretical definitions. This is not always the case given the actual determination of these heights in practice. Hence, an evaluation of these errors will form part of our next study.

6. Conclusions

A high-resolution gravimetric geoid model covering the four main islands of Japan has been developed on a 1 by 1.5 arc-minute grid from EGM2008 and terrestrial gravity data over Japan. It is noted that, although the determined gravimetric geoid represents the geoid over Japan fairly well, there is still a need for more gravity data especially in the northern parts of Japan to obtain a precise geoid model.

The mean and standard deviation of the differences between the determined gravimetric and geometric geoid undulations at 816 GPS/levelling points are -1.66 cm and ±8.29 cm, respectively. The standard deviation can be improved if the errors in the data (GPS, levelling gravity and EGM2008) are minimized. In general, the high-resolution geoid model obtained is of sufficient accuracy and performs better than previous Japanese geoid models.

References

Amos, M. J. and W. E. Featherstone, Preparations for a new gravimetric geoid model of New Zealand, and some preliminary results, NZ Surv., 293, 9–20, 2003.

Andersen, O. B., P. Knudsen, and R. Trimmer, Improved high resolution altimetric gravity field mapping (KMS2002 Global Marine Gravity Field), in AWindow on the Future of Geodesy: Proceedings of the IUGG 23rd General Assembly, Sapporo, Japan, 2003, IAG Symposia, edited by F. Sansò, 128, 326–331, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, 2005.

Boucher, C., Z. Altamimi, M. Feissel, and P. Sillard, Results and analysis of the ITRF94, IERS Technical Note 20, Paris, 1996.

Ekman, M., Impacts on geodynamics phenomena on systems for height and gravity, Bull. Géod., 63, 281–296, 1989.

Featherstone, W. E., J. D. Evans, and J. G. Olliver, A Meissl-modified Vaníček and Kleusberg kernel to reduce the truncation error in gravimetric geoid computations, J. Geod., 72, 154–160, 1998.

Fukuda, Y., J. Kuroda, Y. Takabatake, J. Itoh, and M. Murakami, Improvement of JGEOID93 by the geoidal heights derived from GPS/levelling survey, in Gravity, Geoid and Marine Geodesy, IAG Symposia, edited by J. Segawa, H. Fujimoto, and S. Okubo, 117, 589–596, Springer, 1997.

Ganeko, Y., Astrogeodetic geoid of Japan, Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Special Report, 372, 1976.

Heiskanen, W. A. and H. Moritz, Physical Geodesy, Freeman and Company, San Francisco, 1967.

Imakiire, T. and E. Hakoiwa, JGD2000 (vertical)—The new height system of Japan, Bulletin of the Geographical Survey Institute, 51, 31–51, 2004.

Krige, D. G., A statistical approach to some basic mine valuation problems on the Witwatersrand, J. Chem. Metall. Min. Soc. S. Afr., 52 (6), 119–139, 1951.

Kuroda, J., J. Takabatake, M. Matsushima, and Y. Fukuda, Integration of gravimetric geoid and GPS/leveling survey by least squares collocation, J Geogr Surv Inst., 87, 1–3, 1997 (in Japanese).

Kuroishi, Y., Precise gravimetric determination of geoid in the vicinity of Japan, Bull. Geogr. Surv. Inst., 41, 1–93, 1995.

Kuroishi, Y., An improved gravimetric geoid for Japan, JGEOID98, and relationships to marine gravity data, J. Geod., 74, 745–755, 2001a.

Kuroishi, Y., A new geoid model for Japan, JGEOID2000, in Gravity, Geoid and Geodynamics 2000, IAG Symposia, edited by M. G. Sideris, 123, 329–333, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, 2001b.

Kuroishi, Y., Improved geoid determination for Japan from GRACE and a regional gravity field model, Earth Planets Space, 61, 807–813, 2009.

Kuroishi, Y. and H. Denker, Development of improved gravity field models around Japan, in Gravity, Geoid and Geodynamics 2000, IAG Symposia, edited by M. G. Sideris, 123, 317–322, Springer, New York, 2001.

Kuroishi, Y. and W. Keller, Wavelet approach to improvement of gravity field-geoid modelling for Japan, J. Geophys. Res., 110, B03402, doi:10.1029/2004JB003371, 2005.

Kuroishi, Y., H. Ando, and Y. Fukuda, A new hybrid geoid model for Japan, GSIGEO 2000, J. Geod., 76, 428–436, 2002.

Lemoine, F. G., D. E. Smith, L. Kunz, R. Smith, E. C. Pavlis, N. K. Pavlis, S. M. Klosko, D. S. Chinn, M. H. Torrence, R. G. Williamson, C. M. Cox, K. E. Rachlin, Y. M. Wang, S. C. Kenyon, R. Salman, R. Trimmer, R. H. Rapp, and R. S. Nerem, The development of the NASA GSFC and NIMA joint geopotential model, in Gravity, Geoid and Marine Geodesy, IAG Symposia, edited by J. Segawa, H. Fujimoto, and S. Okubo, 117, 461–469, Springer, 1997.

Martinec, Z., C. Matyska, E. W. Grafarend, and P. Vaníček, On Helmert’s 2nd condensation method, Manuscripta Geodaetica, 18, 417–421, 1993.

Matsumura, S., M. Murakami, and T. Imakiire, Concept of the new Japanese geodetic system, Bull. Geogr. Surv. Inst., 51, 1–9, 2004.

Meissl, P., Preparations for the numerical evaluation of second-order Molodensky-type formulas, Report No. 163, Department of Geodetic Science & Surveying, Ohio State University, Columbus, 1971.

Moritz, H., Linear solutions of the geodetic boundary-value problem, Report No. 79, Department of Geodetic Science and Surveying, Ohio State University, Columbus, 1966.

Moritz, H., Advanced Physical Geodesy, Abacus Press, London, England, 1980.

Olea, R. A., Optimal contour mapping using Universal Kriging, J. Geophys. Res., 79, 695–702, 1974.

Pavlis, N. K., S. A. Holmes, S. C. Kenyon, and J. K. Factor, An Earth gravitational model to degree 2160: EGM2008, The 2008 General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union, Vienna, Austria, April 13–18,2008.

Pellinen, L. P., Accounting for topography in the calculation of quasigeoidal heights and plumb-line deflections from gravity anomalies, Bull. Géod., 63, 57–65, 1962.

Rapp, R. H., Y. M. Wang, and N. K. Pavlis, The Ohio State 1991 geopotential and sea surface topography harmonic coefficient models, Report No. 410, Department of Geodetic Science and Surveying, Ohio State University, Columbus, 1991.

Shichi, R. and A. Yamamoto, List of gravity data measured by Nagoya University, Bull. Nagoya Univ. Museum, Special Report No. 9, Part I, 2001a.

Shichi, R. and A. Yamamoto, List of Gravity Data Measured by Organizations other than Nagoya University, Bull. Nagoya Univ. Museum, Special Report No. 9, Part II, 2001b.

Sideris, M. G. and R. Forsberg, Review of geoid prediction methods in mountainous regions, in Determination of the Geoid, Present and Future, Milan, June 11–13, 1990, IAG Symposia, edited by R. H. Rapp, and F. Sansó, 106, 51–62, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, 1991.

Stokes, G. G., On the variation of gravity on the surface of the Earth, Trans. Camb. Phil. Soc., 8, 672–695, 1849.

Tapley, B., J. Ries, S. Bettadpur, D. Chambers, M. Cheng, F. Condi, B. Gunter, Z. Kang, P. Nagel, R. Pastor, T. Pekker, S. Poole, and F. Wang, GGMO2C—An improved Earth gravity field model from GRACE, J. Geod., 79, 467–478, 2005

Tobita, M., Coordinate transformation software “TKY2JGD” from Tokyo Datum to a geocentric reference system, Japanese Geodetic Datum 2000, Bull. Geogr. Surv. Inst., 97, 31–57, 2001 (in Japanese).

Vanček, P. and A. Kleusberg, The Canadian geoid—Stokesian approach, Manuscr. Geodaet., 12, 86–98, 1987.

Vaníček, P., J. Huang, P. Novák, S. Pagiatakis, M. Véronneau, Z. Martinec, and W. E. Featherstone, Determination of the boundary values for the Stokes-Helmert problem, J. Geod., 73, 180–192, 1999.

Wang, Y. M. and R. H. Rapp, Terrain effects on geoid undulation computations, Manuscripta Geodaetica, 15, 23–29, 1990.

Wichiencharoen, C., Fortran programs for computing geoid undulations from potential coefficients and gravity anomalies, Internal Report, Department of Geodetic Science and Surveying, Ohio State University, Columbus, 1982a.

Wichiencharoen, C., The indirect effects on the computation of geoid undulations, Report No. 336, Department of Geodetic Science and Surveying, Ohio State University, Columbus, 1982b.

Wong, L. and R. Gore, Accuracy of geoid heights from modified Stokes kernels, Geophys. J. R. Astron. Soc, 18, 81–91, 1969.

Yamaguchi, K., K. Nitta, H. Yamamoto, K. Matsuo, M. Machida, M. Murakami, M. Ishihara, S. Nakai, R. Shichi, and A. Yamamoto, The establishment of the Japan Gravity Standardization Net 1996, in Gravity, Geoid and Marine Geodesy, IAG Symposia, edited by J. Segawa, H. Fujimoto, and S. Okubo, 117, 241–248, Springer, 1997.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan for providing the GPS/levelling data covering the four main islands of Japan and other additional data sets. We appreciate the efforts of Nagoya University and other organizations for developing and providing a detailed gravity database covering the south western part of Japan. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their constructive comments and suggestions for improvements of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Odera, P.A., Fukuda, Y. & Kuroishi, Y. A high-resolution gravimetric geoid model for Japan from EGM2008 and local gravity data. Earth Planet Sp 64, 361–368 (2012). https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2011.11.004

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2011.11.004