Summary

Abstract|

Capecitabine is an orally administered prodrug of fluorouracil which is indicated in the US and Europe, in combination with docetaxel, for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer failing anthracycline therapy, and as monotherapy for metastatic breast cancer resistant to paclitaxel and anthracycline therapy (US) or failing intensive chemotherapy (Europe). Capecitabine is also approved for use in metastatic colorectal cancer. Capecitabine is metabolically activated preferentially at the tumour site, and shows antineoplastic activity and synergy with other cytotoxic agents including cyclophosphamide or docetaxel in animal models. Bioavailability after oral administration is close to 100%.

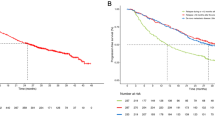

In patients with pretreated advanced breast cancer, capecitabine is effective as monotherapy and also in combination with other agents. Combination therapy with capecitabine 1250 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks of every 3-week cycle plus intravenous docetaxel 75 mg/m2 on day one of each cycle was superior to intravenous monotherapy with docetaxel 100 mg/m2 on day one of each cycle. Capecitabine plus docetaxel significantly reduced the risks of disease progression and death by 35% (p = 0.0001) and 23% (p < 0.05), respectively, and significantly increased median survival (p < 0.05) and objective response rates (p < 0.01). Efficacy has also been demonstrated with capecitabine monotherapy and combination therapy in previously untreated patients in preliminary trials.

The most common adverse effects occurring in patients receiving capecitabine monotherapy include lymphopenia, anaemia, diarrhoea, hand-and-foot syndrome, nausea, fatigue, hyperbilirubinaemia, dermatitis and vomiting (all >25% incidence). While gastrointestinal events and hand-and-foot syndrome occurred more often with capecitabine than with paclitaxel or a regimen of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil (CMF), neutropenic fever, arthralgia, pyrexia and myalgia were more common with paclitaxel, and nausea, stomatitis, alopecia and asthenia were more common with CMF. The incidence of adverse effects and hospitalisation was similar in patients receiving capecitabine plus docetaxel and those receiving docetaxel monotherapy.

In conclusion, capecitabine, an oral prodrug of fluorouracil which is activated preferentially at the tumour site, is an effective and convenient addition to the intravenous polychemotherapeutic treatment of advanced breast cancer in pretreated patients, and also has potential as a component of first-line combination regimens. Combined capecitabine plus docetaxel therapy resulted in similar rates of treatment-related adverse effects and hospitalisation to those seen with docetaxel monotherapy. Capecitabine is also effective as monotherapy in pretreated patients and phase II data for capecitabine as first-line monotherapy are also promising. While gastrointestinal effects and hand-and-foot syndrome occur often with capecitabine, the tolerability profile was comparatively favourable for other adverse effects (notably, neutropenia and alopecia).

Overview of Pharmacology|

Capecitabine is an oral fluoropyrimidine which undergoes several metabolic changes in vivo, ultimately yielding fluorouracil. This occurs preferentially in tumour tissue and leads to subsequent formation of fluorodeoxyuridine mono-phosphate and fluorouridine triphosphate. Capecitabine demonstrates antineoplastic activity in human mammary tumour xenograft models, with synergistic effects when used in combination with other cytotoxic agents including cyclophosphamide and docetaxel.

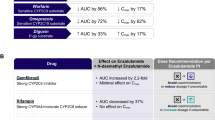

Pharmacokinetic studies with capecitabine have been performed in patients with solid tumours, many of which were colorectal but including some breast tumours. The oral bioavailability of capecitabine is nearly 100%. Maximum plasma concentrations and area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) of capecitabine showed linear increases with dosage and were decreased when capecitabine was administered with food. Elimination of capecitabine is primarily renal; in patients with severe renal impairment, use of capecitabine is contraindicated. Capecitabine increased the AUC and decreased clearance of a single dose of warfarin. Patients receiving concomitant capecitabine and oral coumarin-derivative anticoagulant therapy therefore require frequent monitoring of their anticoagulant response. The pharmacokinetics of capecitabine are not significantly affected by paclitaxel or docetaxel.

Therapeutic Efficacy|

Oral capecitabine 1250 or 1255 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks in every 3 has shown efficacy in prospective trials as monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced breast cancer. Objective response rates with capecitabine monotherapy were 36% (vs a similar rate of 26% with intravenous paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) in women with disease resistant to or failing anthracycline therapy, 18 to 41% in those with disease resistant to or failing taxane therapy, and 43, 57 and 70% in those with relapsed disease after high-dose chemotherapy plus autologous stem cell support.

A randomised nonblind phase III trial has demonstrated the efficacy of capecitabine as part of a combination regimen in women with advanced breast cancer resistant to or failing anthracycline therapy. Capecitabine 1250 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks of every 3-week cycle plus intravenous docetaxel 75 mg/m2 administered over a 1-hour infusion on day one of each cycle was superior to intravenous docetaxel 100 mg/m2 monotherapy on day one of each cycle in women with advanced breast cancer refractory to previous anthracycline therapy. The risks of disease progression and death were reduced by 35% (p = 0.0001) and 23% (p < 0.05) with capecitabine plus docetaxel. Median survival was longer with the combination than with docetaxel alone (14.5 vs 11.5 months, p < 0.05) and objective response rates were higher (42% vs 30%, p < 0.01). Smaller non-comparative trials demonstrated objective response rates of 52–63% in women pretreated with anthracyclines and/or taxanes who received therapy combining capecitabine with intravenous paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 every 3 weeks, intravenous vinorelbine 2530 mg/m2/week or (tumour overexpressing HER2) intravenous trastuzumab 2 mg/kg/week.

First-line monotherapy with capecitabine 1255 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks in every 3 resulted in an objective response rate of 30% in women aged ≥55 years versus 16% in those receiving intravenous cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 plus methotrexate 40 mg/m2 and fluorouracil 600 mg/m2 (CMF) once every 3 weeks. Objective response rates of 49, 67 and 76% were seen with combination first-line therapy of capecitabine 825 to 1000 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks in every 3 plus paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 once every 3 weeks, vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of each cycle, or epirubicin plus docetaxel, both 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks in noncomparative trials.

Dosage reduction for adverse effects does not appear to compromise the efficacy of capecitabine.

Two pharmacoeconomic studies have suggested that there may be cost savings associated with treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer with capecitabine and docetaxel compared with docetaxel alone. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of $CAN4254 per life-year gained and $US5520 per quality-adjusted life year gained were reported.

Tolerability|

Adverse effects associated with administration of capecitabine monotherapy 1255 mg/m2 twice daily for 2 weeks in every 3, in six clinical trials in patients with breast or colorectal cancer (n = 570) and occurring at an incidence of ≥5%, were lymphopenia, anaemia, diarrhoea, hand-and-foot syndrome, nausea, fatigue, hyperbilirubinaemia, dermatitis and vomiting (all >25% incidence). Adverse effects graded level 4 included lymphopenia (10% incidence), hyperbilirubinaemia (3%), neutropenia (2%), diarrhoea (2%), dehydration (1%), thrombocytopenia (1%) and anaemia (1%), while those graded level 3 were lymphopenia (36%), gastrointestinal effects (27%), hyperbilirubinaemia (14%), hand-and-foot syndrome (13%), and fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, dehydration, anaemia, dermatitis, headache, and thrombocytopenia (all ≤5%).

Adverse effects were reported by most patients receiving oral capecitabine monotherapy or comparative agents in randomised nonblind clinical trials. Gastrointestinal effects and hand-and-foot syndrome occurred more often with oral capecitabine than with either intravenous paclitaxel or intravenous CMF, while neutropenic fever, arthralgia, pyrexia and myalgia were more common with paclitaxel, and nausea, stomatitis, alopecia and asthenia were more common with the CMF regimen.

In patients receiving combination therapy, median delivered capecitabine and docetaxel doses were 77% and 87% of the planned doses. Doses were mainly reduced because of hand-and-foot syndrome, diarrhoea or stomatitis. Treatment-related adverse effects occurred in 98% of patients in the combination therapy group compared with 94% of patients receiving docetaxel monotherapy. The incidences of gastrointestinal adverse effects and hand-and-foot syndrome were higher among capecitabine plus docetaxel recipients, while neutropenic fever, arthralgia and pyrexia occurred more frequently among recipients of docetaxel monotherapy.

Dosage and Administration|

In the US and Europe, capecitabine in combination with docetaxel is indicated for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer after failure of prior anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. Capecitabine monotherapy is indicated in patients with metastatic breast cancer resistant to both paclitaxel and an anthracycline-containing chemotherapy regimen or in those resistant to paclitaxel and for whom further anthracycline therapy is not indicated (US) or failing intensive chemotherapy (Europe). The recommended dosage is 1250 mg/m2 administered twice daily (equivalent to 2500 mg/m2/day) for 14 days followed by a 7-day rest. Capecitabine tablets should be taken within 30 minutes after a meal. Capecitabine is also approved for use in metastatic colorectal cancer.

Capecitabine is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to fluorouracil and in those with severe renal impairment; in Europe it is also contraindicated in those with severe hepatic impairment, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency, or severe leucopenia, neutropenia or thrombocytopenia. Dosages should be reduced in patients with moderate renal impairment. Patients taking coumarin anticoagulants or phenytoin concomitantly with capecitabine should be regularly monitored; in the US, there is a boxed warning recommending frequent monitoring with the use of capecitabine and coumarin anticoagulants. Concomitant use with allopurinol should be avoided. Capecitabine toxicity occurring during monotherapy can be managed with symptomatic treatment or dose modification.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kinsinger LS, Harris R, Woolf SH, et al. Chemoprevention of breast cancer: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137: 59–67

Mathers CD, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality and survival by site for 14 regions of the world [online]. Available from URL: http://www3.who.int/whosis [Accessed 2002 Nov 13]

Khayat D. Overview of the role of chemotherapy in the management of metastatic breast cancer. Drugs Today 2002; 38 Suppl. A: 3–10

Danova M, Porta C, Ferrari S, et al. Strategies of medical treatment for metastatic breast cancer (review). Int J Oncol 2001 Oct; 19(4): 733–9

Update: NCCN practice guidelines for the treatment of breast cancer. Oncology (Huntington) 1999 May; 13: 41–66

Dooley M, Goa KL. Capecitabine. Drugs 1999; 58: 69–76

McGavin JK, Goa KL. Capecitabine: a review of its use in the treatment of advanced breast or metastatic colorectal cancer. Drugs 2001; 61: 2309–26

Ishikawa T, Utoh M, Sawada N, et al. Tumor selective delivery of 5-fluorouracil by capecitabine, a new oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, in human cancer xenografts. Biochem Pharmacol 1998; 55: 1091–7

Schüller J, Cassidy J, Dumont E, et al. Preferential activation of capecitabine in tumor following oral administration to colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2000; 45: 291–7

Endo M, Shinbori N, Fukase Y, et al. Induction of thymidine phosphorylase expression and enhancement of efficacy of capecitabine or 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine by cyclophosphamide in mammary tumor models. Int J Cancer 1999 Sep 24; 83: 127–34

Ishikawa T, Sekiguchi F, Fukase Y, et al. Positive correlation between the efficacy of capecitabine and doxifluridine and the ratio of thymidine phosphorylase to dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activities in tumors in human cancer xenografts. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 685–90

Ishikawa T, Fukase Y, Yamamoto T, et al. Antitumor activities of a novel fluoropyrimidine, N4-pentyloxycarbonyl-5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine (capecitabine). Biol Pharm Bull 1998; 21(7): 713–7

Fujimoto-Ouchi K, Tanaka Y, Tominaga T. Schedule dependency of antitumor activity in combination therapy with capecitabine/5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine and docetaxel in breast cancer models. Clin Cancer Res 2001 Apr; 7(4): 1079–86

Wright TL, Twelves CJ. Improved survival in advanced breast cancer with docetaxel and capecitabine in combination: biological synergy or an artefact of trial design? Eur J Cancer 2002; 38: 1957–60

Mackean M, Planting A, Twelves C, et al. Phase I and pharmalogic study of intermittent twice-daily oral therapy with capecitabine in patients with advanced and/or metastatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16(9): 2977–85

Budman DR, Meropol NJ, Reigner B, et al. Preliminary studies of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate: capecitabine. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16(5): 1795–802

Pronk LC, Vasey P, Sparreboom A, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the combination of capecitabine and docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br J Cancer 2000; 83: 22–9

Reigner B, Blesch K, Weidekamm E. Clinical pharmacokinetics of capecitabine. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40: 85–104

Reigner B, Verweij J, Dirix L, et al. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of capecitabine and its metabolites following oral administration in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 1998; Apr 4: 941–8

Judson IR, Beale PJ, Trigo JM, et al. A human capecitabine excretion balance and pharmacokinetic study after administration of a single oral dose of 14 C-labelled drug. Invest New Drugs 1999; 17: 49–56

Roche Laboratories Inc. Xeloda™ (capecitabine) tablets. US product information. Nutley, (NJ): Roche Laboratories Inc, 2002

Twelves C, Glynne-Jones R, Cassidy J, et al. Effect of hepatic dysfunction due to liver metastases on the pharmacokinetics of capecitabine and its metabolites. Clin Cancer Res 1999; 5: 1696–702

Villalona-Calero MA, Weiss GR, Burris HA, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine in combination with paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid malignancies. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 1915–25

O’Shaughnessy J, Miles D, Vukelja S, et al. Superior survival with capecitabine plus docetaxel combination therapy in anthracycline-pretreated patients with advanced breast cancer: phase III trial results. J Clin Oncol 2002 Jun 15; 20(12): 2812–23

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 205–16

Talbot DC, Moiseyenko V, Van Belle S, et al. Randomised, phase II trial comparing oral capecitabine (Xeloda®) with paclitaxel in patients with metastatic/advanced breast cancer pretreated with anthracyclines. Br J Cancer 2002 May 6; 86(9): 1367–72

Blum JL, Jones SE, Buzdar AU, et al. Multicenter phase II study of capecitabine in paclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17(2): 485–93

Blum JL, Dieras V, Lo Russo PM, et al. Multicenter, phase II study of capecitabine in taxane-pretreated metastatic breast carcinoma patients. Cancer 2001 Oct 1; 92: 1759–68

Cervantes G, Torrecillas L, Erazo AA, et al. Capecitabine (Xeloda) as treatment after failure to taxanes for metastatic breast cancer [abstract no. 469]. 36th Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2000 May 20; 19: 121a

Fumoleau P, Largillier R, Trillet-Lenoir V, et al. Capecitabine (Xeloda) in patients with advanced breast cancer (ABC), previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes: results of a large phase II study [abstract no. 244]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2002 May 18; 21(1): 62a

Jakob A, Bokemeyer C, Knop S, et al. Capecitabine in patients with breast cancer relapsing after high-dose chemotherapy plus autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation — a phase II study. Anticancer Drugs 2002 Apr; 13(4): 405–10

Reichardt P, von Minckwitz G, Lück HJ, et al. Capecitabine: the new standard in metastatic breast cancer failing anthracycline and taxane-containing chemotherapy? Mature results of a large multicenter phase II trial [abstractno. 699]. EJC 2001 Oct; 37 (Suppl.6): S191

Wong ZW, Wong KK, Chew L, et al. Capecitabine as an oral chemotherapeutic agent in the treatment of refractory metastatic breast cancer [abstract no. 466]. 36th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, New Orleans, (LA), 2000 May 20; 19: 120

Bashey A, Sundaram S, Corringham S, et al. Use of capecitabine as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer relapsing after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell support. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2001; 13(6): 434–7

Guthrie TH, Agaliotis DP, Gaddis TG. Capecitabine (C) has activity in breast cancer patients (BCP) progressing after autologous peripheral stem cell transplant (AuPSCT) [abstract no. 356]. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999; 57(1): 90

Leonard RCF, Twelves C, Breddy J, et al. Capecitabine named-patient programme for patients with advanced breast cancer: the UK experience. Eur J Cancer 2002; 38: 2020–4

O’Shaughnessy J, Blum J, Baylor-Charles A. A retrospective evaluation of the impact of dose reduction in patients treated with Xeloda (capecitabine) [abstract no. 400]. 36th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, New Orleans, (LA), 2000 May 20; 19: 104a

Nolè F, Catania C, Mandalà M, et al. Phase 1 study of vinorelbine (V) and capecitabine (C) in advanced breast cancer (ABC) [abstract no. 539]. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000; 64: 125

Biganzoli L, Bonnefoi H, Mauriac L, et al. Cyclophosphamide (C) — epirubicine (E) — capecitabine (X) combination, CEX: a safe and active regimen in the treatment of locally advanced/inflammatory (LA/I) or large operable (LO) breast cancer (BC). An EORTC-IDBBC study [abstract]. Eur J Cancer 2001 Oct; 37 Suppl. 6: 146

Scarfe AG, BodnarD, Tonkin K, et al. Interim results of a phase II study of weekly docetaxel (Taxotere®) combined with intermittent capecitabine (Xeloda®) for patients with anthracycline pre-treated metastatic breast cancer [online]. Available from URL: www.asco.org (abstract no. 1984) [Accessed 2002 Oct 8]

Batista N, Perez Manga G, Constenia M, et al. Phase II study of capecitabine (Xeloda) in combination with paclitaxel (P) in the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (BC): preliminary results [abstract no. 130P]. Ann Oncol 2000; 11 Suppl. 4: 32

Welt A, von Minckwitz G, Borquez D, et al. Capecitabine in combination with vinorelbin in pretreated patients with metastatic breast cancer — results of an extended phase II study [abstract no. 202P]. Ann Oncol 2002; 13 Suppl.5: 56

Bangemann N, Kuhle A, Ebert A, et al. Capecitabine combined with trastuzumab in the therapy of intensively pretreated HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer (MBC) [abstract no. 653P]. Ann Oncol 2000; 11 Suppl. 4: 143

Oshaughnessy JA, Blum J, Moiseyenko V, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase II trial of oral capecitabine (Xeloda) vs. a reference arm of intravenous CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil) as first-line therapy for advanced/metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2001 Sep; 12(9): 1247–54

Meza LA, Amin B, Horsey M, et al. A phase II study of capecitabine in combination with paclitaxel as first or second line therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer [abstract no. 2029]. 37th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, San Francisco (CA); 2001 May 12; 20 (Part 2): 70

Venturini M, Catzeddu T, Durando A, et al. A multicenter phase II study of TEX regimen (Taxotere, Epirubicin, and Xeloda) as a first line treatment in advanced breast cancer [abstract no. B32]. Ann Oncol 2001; 12 Suppl. 4: 25

Kattan J, Ghosn M, Farhat F, et al. Phase II study of vinorelbine (Navelline) and capecitabine (C) combination (Navcap) as first line treatment of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) [abstract no. 201P]. Ann Oncol 2002; 13 Suppl. 5: 56

Angiolini C, Venturini M, Del Mastro L, et al. Capecitabine in association with epirubicin (E) and docetaxel (D) as first line chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer: a dose-finding study [abstract no. 529]. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000 Nov; 64: 123

Malfair Taylor S, Barnett J, Chia S. Population based cost-effectiveness analysis of combination capecitabine and docetaxel (DC) versus single agent docetaxel (D) in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) following an anthracycline regimen [abstract no. 113]. Eur J Cancer 2002 Mar; 38 Suppl. 3: S67

Hornberger JC, Jamieson C, O’ Shaughnessy J. Economic evaluation of capecitabine-docetaxel combination treatment of metastatic breast cancer: a microsimulation study. Crystal City, Arlington (VA): International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 2002 May 19-2002

Roche Laboratories Inc. Xeloda™ (capecitabine) tablets package insert. Nutley, (NJ): Roche Laboratories Inc., 1998

Europe approves Xeloda (capecitabine) for breast cancer [online]. Available from URL: www.pslgroup.com/dg/214F7 E.htm [Accessed 2002 Nov 13]

Roche Limited. Xeloda (capecitabine) tablets. European summary of product characteristics. Welwyn Garden City, UK: Roche Limited, 2001

Piccart MJ, Awada A. State-of-the-art chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol 2000 Oct; 27 5 Suppl. 9: 3–12

Esteva FJ, Valero V, Pusztai L, et al. Chemotherapy of metastatic breast cancer: what to expect in 2001 and beyond. Oncologist 2001; 6(2): 133–46

Esteva FJ. The current status of docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. Oncology (Huntingt) 2002 Jun; 16 (6 Suppl. 6): 17–26

Ratain MJ. Dear doctor: we really are not sure what dose of capecitabine you should prescribe for your patient. J Clin Oncol 2002 Mar 15; 20(6): 1434–5

Michaud LB, Gauthier MA, Wojdylo JR, et al. Improved therapeutic index with lower dose capecitabine in metastatic breast cancer (MBC) patients (Pts) [abstract no. 402]. 36th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, New Orleans (LA); 2000 May 20; 19: 104

O’Shaughnessy JA. Potential of capecitabine as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer: dosing recommendations in patients with diminished renal function [letter]. Ann Oncol 2002 Jun; 13(6): 983–4

Roche Products Limited. 2002

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Various sections of the manuscript reviewed by: D.R. Budman, Don Monti Division of Oncology, North Shore University Hospital, New York, New York, USA; F.M. Muggia, Kaplan Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA; D. Papamichael, Department of Medical Oncology, BOC Oncology Centre, Strovolos, Nicosia, Cyprus; P.N. Plowman, Department of Radiotherapy, St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, England; C. Twelves, Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Research UK, Glasgow, Scotland.

Data Selection

Sources: Medical literature published in any language since 1980 on capecitabine, identified using Medline and EMBASE, supplemented by AdisBase (a proprietary database of Adis International). Additional references were identified from the reference lists of published articles. Bibliographical information, including contributory unpublished data, was also requested from the company developing the drug.

Search strategy: Medline search terms were ‘capecitabine’ and ‘breast-neoplasms’. EMBASE search terms were ‘capecitabine’ and ‘breast cancer’. AdisBase search terms were ‘capecitabine’ and ‘breast-cancer’. Searches were last updated 12 December, 2002.

Selection: Studies in patients with advanced breast cancer who received capecitabine. Inclusion of studies was based mainly on the methods section of the trials. When available, large, well controlled trials with appropriate statistical methodology were preferred. Relevant pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic data are also included.

Index terms: capecitabine, breast cancer, advanced breast cancer, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, therapeutic use.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wagstaff, A.J., Ibbotson, T. & Goa, K.L. Capecitabine. Drugs 63, 217–236 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200363020-00009

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200363020-00009