Abstract

Background: Utilities are the quantification of the perceived quality of life associated with any health state. They are used to calculate QALYs, the outcome measure in cost-utility analysis. Generally measured through surveys of individuals, utilities often contain apparent or unapparent errors that can bias resulting values and QALYs calculated from these values.

Objective: The aim of this study was to improve direct health utility elicitation methodology through the identification of the types of survey responses that indicate errors and objections, and the reasons underlying them.

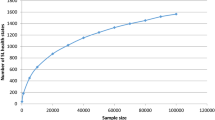

Methods: We conducted a systematic review of the medical (PubMed), economics (EconLit) and psychology (PsycINFO) literature from 1975 through June 2010 for articles describing the types and frequency of errors and objections in directly elicited utility survey responses, and strategies to address these responses. Primary data were collected through an internet-based utility survey (standard gamble) of community members to identify responses that indicate error or objections. A qualitative telephone survey was conducted among a subset of respondents with these types of responses using an open-ended protocol to elicit rationales for them.

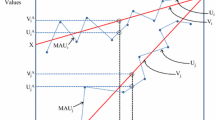

Results: A total of 11 papers specifically devoted to errors, objections and invariance in utility responses have been published since the mid-1990s. Error/objection responses can be broadly categorized into ordering errors (which include illogical and inconsistent responses) and objections/invariance (which include missing data, protest responses and refusals to trade time or risk in utility questions). Reported frequencies of respondents making ordering errors ranged from 5% to 100%, and up to 35% of respondents have been reported as objecting to the survey or task in some manner. Changes in the design, administration and analysis of surveys can address these potentially problematic responses.

Survey data (n = 398) showed that individuals who provided invariant responses (n = 26) reported the lowest level of difficulty with the survey and often identified as religious (23% of invariant responders found the survey difficult vs 63% of all responders, and 77% of invariant responders identified as religious compared with 56% of entire sample; p < 0.05 for both). Respondents who provided illogical responses (n = 50) were less likely to be college educated (56% of illogical responders vs 73% of entire sample; p < 0.05), and less likely to be confident in their responses (62% vs 75% of entire sample; p < 0.05). Qualitative interviews (n = 42) following the survey revealed that the majority of ordering errors were a result of confusion, lack of attention or difficulty in responding to the survey on the part of the respondent, while invariant responses were often considered and thoughtful reactions to the premise of valuing health using the standard gamble task.

Conclusions: Rationales for error/objection responses include difficulty in articulating preferences or misunderstanding with a complex survey task, and also thoughtful and considered protestations to the task. Mechanisms to correct unintentional errors may be useful, but cannot address intentional responses to elements of the measurement task. Identification and analysis of the prevalence of errors and objections in responses in utility data sets are essential to understanding the accuracy and precision of utility estimates and analyses that depend thereon.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Lomas J, et al. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care 1999; 11(3): 187–92

Gregorich SE. Do self-report instruments allow meaningful comparisons across diverse population groups? Testing measurement invariance using the confirmatory factor analysis framework. Med Care 2006; 44(11 Suppl. 3): S78–94

Fischhoff B. Value elicitation: is there anything there? Am Psychol 1990; 46: 835–47

Robinson A, Dolan P, Williams A. Valuing health status using VAS and TTO: what lies behind the numbers? Soc Sci Med 1997; 45: 1289–97

Lenert L, Kaplan RM. Validity and interpretation of preference-based measures of health-related quality of life. Med Care 2000; 38(9 Suppl.): II138–50

Craig BM, Ramachandran S. Relative risk of a shuffled deck: a generalizable logical consistency criterion for sample selection in health state valuation studies. Health Econ 2006; 15(8): 835–48

Gold M, Patrick D, Torrance G, et al. Identifying and valuing outcomes. In: Gold M, Siegel J, Russell L, et al., editors. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996: 82–134

WareJr J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34(3): 220–33

Badia X, Roset M, Herdman M. Inconsistent responses in three preference-elicitation methods for health states. Soc Sci Med 1999; 49: 943–50

Fonta WM, Ichoku HE, Kabubo-Mariara J. The effect of protest zeros on estimates of willingness to pay in healthcare contingent valuation analysis. Applied Health Econ Health Policy 2010; 8(4): 225–37

Lenert LA, Treadwell JR. Effects on preferences of violations of procedural invariance. Med Decis Making 1999; 19(4): 473–81

Lenert LA. The reliability and internal consistency of an internet-capable computer program for measuring utilities. Qual Life Res 2000; 9(7): 811–7

Lenert LA, Sturley A, Rupnow M. Toward improved methods for measurement of utility: automated repair of errors in elicitations. Med Decis Making 2003; 23(1): 67–75

Fowler Jr FJ, Cleary PD, Massagli MP, et al. The role of reluctance to give up life in the measurement of the values of health states. Med Decis Making 1995; 15(3): 195–200

Rutten-van Mölken MP, Bakker CH, van Doorslaer EK, et al. Methodological issues of patient utility measurement: experience from two clinical trials. Med Care 1995; 33(9): 922–37

Lamers LM, Stalmeier PF, Krabbe PF, et al. Inconsistencies in TTO and VAS values for EQ-5D health states. Med Decis Making 2006; 26(2): 173–81

Bravata DM, Nelson LM, Garber AM, et al. Invariance and inconsistency in utility ratings. Med Decis Making 2005; 25(2): 158–67

Devlin NJ, Hansen P, Kind P, et al. Logical inconsistencies in survey respondents’ health state valuations: a methodological challenge for estimating social tariffs. Health Econ 2003; 12(7): 529–44

Giesler RB, Ashton CM, Brody B, et al. Assessing the performance of utility techniques in the absence of a gold standard. Med Care 1999; 37(6): 580–8

Lenert LA, Morss S, Goldstein MK, et al. Measurement of the validity of utility elicitations performed by computerized interview. Med Care 1997; 35(9): 915–20

Dolan P, Kind P. Inconsistency and health state valuations. Soc Sci Med 1996; 42(4): 609–15

Devlin NJ, Hansen P, Selai C. Understanding health state valuations: a qualitative analysis of respondents’ comments. Qual Life Res 2004; 13(7): 1265–77

Kaplan RM. The minimally clinically important difference in generic utility-based measures. COPD 2005; 2(1): 91–7

Prosser LA, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM, et al. Values for preventing influenza-related morbidity and vaccine adverse events in children. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005 Mar 21; 3: 18

Prosser LA, Wittenberg E. Valuing children’s health: response issues with using parents as proxies [abstract]. Med Decis Making 2007; 25(1): E57

Bleichrodt H, Pinto Prades JL. New evidence of preference reversals in health utility measurement. Health Econ 2009; 18(6): 713–26

Lenert L, Sturley A, Watson M. iMPACT3: internet-based development and administration of utility elicitation protocols. Med Decis Making 2002; 22: 464–74

Lenert LA, Sturley AP, Rapaport MH, et al. Public preferences for health states with schizophrenia and a mapping function to estimate utilities from positive and negative symptom scale scores. Schizophr Res 2004; 71(1): 155–65

Corso P, Hammitt J, Graham J. Valuing mortality-risk reduction: using visual aids to improve the validity of contingent valuation. J Risk Uncertain 2001; 23(2): 165–84

Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. The effect of format on parents’ understanding of the risks and benefits of clinical research: a comparison between text, tables, and graphics. J Health Commun 2010; 15(5): 487–501

Attema AE, Brouwer WB. Can we fix it? Yes we can! But what? A new test of procedural invariance in TTO measurement. Health Econ 2008; 17(7): 877–85

Wright DR, Wittenberg E, Swan JS, et al. Methods for measuring temporary health states for cost-utility analyses. Pharmacoeconomics 2009; 27(9): 713–23

Attema AE, Brouwer WB. The value of correcting values: influence and importance of correcting TTO scores for time preference. Value Health 2010; 13(8): 879–84

Attema AE, Brouwer WB. On the (not so) constant proportional trade-off in TTO. Qual Life Res 2010; 19(4): 489–97

Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, et al. Using discrete choice experiments to understand preferences for quality of life: variance-scale heterogeneity matters. Soc Sci Med 2010; 70(12): 1957–65

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008; 26(8): 661–77

Craig BM, Busschbach JJ, Salomon JA. Modeling ranking, time trade-off, and visual analog scale values for EQ-5D health states: a review and comparison of methods. Med Care 2009; 47(6): 634–41

Bansback N, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, et al. Using a discrete choice experiment to estimate societal health state utility values [HEDS discussion paper 10/03]. Sheffield: Health Economics and Decision Science (HEDS) Section at the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), 2010

Craig BM, Busschbach JJ, Salomon JA. Keep it simple: ranking health states yields values similar to cardinal measurement approaches. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62(3): 296–305

Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Marley AA, et al. Rescaling quality of life values from discrete choice experiments for use as QALYs: a cautionary tale. Popul Health Metr 2008 Oct 22; 6: 6

Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, et al. Best-worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ 2007; 26(1): 171–89

Spitzer W, Dobson A, Hall J. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-Index for use by physicians. J Chronic Disease 1981; 34: 585–97

US Census Bureau. Resident population estimates of the United States by sex, race, and hispanic origin: April 1, 1990 to July 1, 1999 with short-term projection to November 1, 2000. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2001 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.census.gov/population/estimates/nation/intfile3-1.txt [Accessed 2010 Jan 4]

US Census Bureau. State and county quickfacts. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html [Accessed 2010 Jan 4]

US Census Bureau. Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) supplement. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2008 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/cpstables/032009/hhinc/new06_000.htm [Accessed 2010 Jan 4]

US Census Bureau. The 2011 statistical abstract: the national data book. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2010 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population/religion.html [Accessed 2010 Jan 4]

US Census Bureau. America’s families and living arrangements: 2008. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2008 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam/cps2008.html [Accessed 2010 Jan 4]

Gregory R, Lichtenstein S, Slovic P. Valuing environmental resources: a constructive approach. J Risk Uncertain 1993; 7: 177–97

Payne J, Bettman J, Schkade D. Measuring constructed preferences: toward a building code. J Risk Uncertain 1999; 19:1–3, 243–70

Prosser L, Hammitt J, Keren R. Measuring health preferences for use in cost-utility and benefit analyses of interventions in children: theoretical and methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics 2007; 25(9): 713–26

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for excellent research assistance provided by Melissa Gardel and Andrew Hart, and the insightful comments and suggestions provided by two anonymous reviewers. They also acknowledge the contribution of survey participants, without whom this research would not have been possible.

This work was presented in part at the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research annual meeting, Orlando (FL, USA), May 2009 and the American Society of Health Economists’ biannual meeting, Ithaca (NY, USA), June 2010. This work was supported by grant number 7 K02 HS014010 to E. Wittenberg from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The funding agreement ensured the independence of the work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wittenberg, E., Prosser, L.A. Ordering errors, objections and invariance in utility survey responses. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 9, 225–241 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2165/11590480-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11590480-000000000-00000