Abstract

Antiarrhythmic drugs need to be initiated in up to 70% of patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) in order to treat atrial tachyarrhythmias, decrease the frequency of defibrillator shocks, and terminate ventricular arrhythmias along with antitachycardia pacing.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) occurs in about 20% of patients with ICDs (the majority with congestive heart failure [CHF]). Antiarrhythmic drugs are initiated for this indication in 2–20% of the ICD population. Data from CHF-STAT (Congestive Heart Failure: Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy; amiodarone vs placebo) and DIAMOND-AF (Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality ON Dofetilide — Atrial Fibrillation; dofetilide vs placebo) support the approach that restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm might be beneficial in CHF, even though no study has specifically addressed the CHF population with ICDs. Further clarification on potential benefits of rhythm control in CHF-associated AF will come from the AF-CHF (Atrial Fibrillation and Congestive Heart Failure) trial that is currently underway.

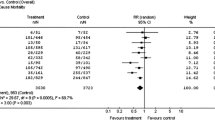

The vast majority of patients with ICDs will have discharges of their devices during follow-up. Although class III antiarrhythmic drugs are widely considered to be effective for prophylaxis against frequent shocks, there are surprisingly few controlled studies that demonstrate this. In contrast to conflicting amiodarone data, sotalol has been found to be effective in preventing shocks from ICDs in prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled studies. A large study (SHIELD; SHock Inhibition Evaluation with azimiLiDe) has shown that azimilide significantly reduces ventricular tachyarrhythmia recurrence, thereby reducing the burden of symptomatic ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Other novel antiarrhythmic drugs, such as dofetilide or dronedarone, as well as different strategies (e.g. in the OPTIC [Optimal Pharmacological Therapy in Implantable Cardioverter] trial; β-adrenoceptor antagonist therapy alone, amiodarone plus β-adrenoceptor antagonist therapy, or sotalol alone) for the prevention of ICD shocks are under evaluation.

The majority of antiarrhythmic drugs, including sotalol, dofetilide, and azimilide, have no effect on, or are even associated with a decrease in, defibrillation thresholds in humans. Amiodarone, in contrast, has been shown to be related to higher defibrillation thresholds at implant and during follow-up of monophasic devices. Potential cardiac (e.g. ventricular proarrhythmia, negative inotropic effect) and drug-specific non-cardiac adverse effects are a frequent cause for drug discontinuation and need to be considered when initiating and maintaining antiarrhythmic drug therapy.

In conclusion, antiarrhythmic drugs are frequently used in ICD patients, the main indications being treatment of atrial tachyarrhythmias and prevention of ICD shocks. Despite potential adverse effects, antiarrhythmics can be administered safely, as long as ICD/drug interactions are appreciated. Controlled studies that will further define the role of concomitant antiarrhythmic drug utilization in patients with ICDs are underway.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Engelstein ED, Zipes DP. Sudden cardiac death. In: Alexander RW, Schlant RC, Fuster V, editors. Hurst’s the heart. 9th ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 1998: 1081–112.

Naccarelli GV. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: expanding indications. Curr Opin Cardiol 2004; 19: 317–22.

DiMarco JP. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1836–47.

Hine LK, Gross TP, Kennedy DL. Outpatient antiarrhythmic drug use from 1970 through 1986. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149: 1524–7.

Al-Khatib SM, LaPointe NMA, Curtis LH, et al. Outpatient prescribing of antiarrhythmic drugs from 1995 to 2000. Am J Cardiol 2003; 91: 91–4.

Steinberg JS, Martins J, Sadanandan S, et al. Antiarrhythmic drug use in the implantable defibrillator arm of the Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Study. Am Heart J 2001; 142: 520–9.

Curtis AB. Filling the need for new antiarrhythmic drugs to prevent shocks from implantable cardioverter defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43: 44–6.

Fuster V, Ryden LE, Asinger RW, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation). Developed in collaboration with the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 2001; 104: 2118–50.

Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, et al. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med 1982; 306: 1018–22.

Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, et al. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba follow-up study. Am J Med 1995; 98: 476–84.

Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions: the SOLVD investigators [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 1992; 327 (24): 1768]. N Engl J Med 1992; 327 (10): 685–691.

Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1429–1435.

Deneke T, Lawo T, Gerritse B, et al. Mortality of patients with implanted cardioverter/defibrillators in relation to episodes of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2004; 6: 151–8.

Manz M, Jung W, Luderitz B. Interactions between drugs and devices: experimental and clinical studies. Am Heart J 1994; 127: 978–84.

Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998; 98: 946–52.

Stein KM, Euler DE, Mehra R, et al. Do atrial tachyarrhythmias beget ventricular tachyarrhythmias in defibrillator recipients? J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 40: 335–40.

Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1825–33.

Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1834–40.

Deedwania PC, Singh BN, Ellenbogen K, et al. Spontaneous conversion and maintenance of sinus rhythm by amiodarone in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation: observations from the veterans affairs congestive heart failure survival trial of antiarrhythmic therapy (CHF-STAT). The Department of Veterans Affairs CHF-STAT investigators. Circulation 1998; 98: 2574–9.

Pedersen OD, Bagger H, Keller N, et al. Efficacy of dofetilide in the treatment of atrial fibrillation-flutter in patients with reduced left ventricular function: a Danish Investigation of Arrhythmia and Mortality ON Dofetilide (DIAMOND) substudy. Circulation 2001; 104: 292–6.

Rationale and design of a study assessing treatment strategies of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure: the Atrial Fibrillation and Congestive Heart Failure (AF-CHF) trial. Am Heart J 2002; 144: 597–607.

Nanthakumar K, Dorian P, Paquette M, et al. Is inappropriate implantable defibrillator shock therapy predictable? J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2003 Jun; 8(3): 215–20.

Greene M, Newman D, Geist M, et al. Is electrical storm in ICD patients the sign of a dying heart? Outcome of patients with clusters of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Europace 2000 Jul; 2(3): 263–9.

Exner DV, Pinski SL, Wyse G, et al. Electrical storm presages nonsudden death: the Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) trial. Circulation 2001; 103: 2066–71.

Credner SC, Klingenheben T, Mauss O, et al. Electrical storm in patients with transvenous implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: incidence, management and prognostic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32: 1909–15.

Greene M, Newman D, Geist M, et al. Is electrical storm in ICD patients the sign of a dying heart? Outcome of patients with clusters of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Europace 2000; 2: 263–9.

Tzivoni D, Banai S, Schuger C, et al. Treatment of torsade de pointes with magnesium sulfate. Circulation 1988; 77: 392–7.

DiSegni E, Klein HO, David D, et al. Overdrive pacing in quinidine syncope and other long QT-interval syndromes. Arch Intern Med 1980; 140: 1036–40.

Cardiac Arrest in Seattle: Conventional versus Amiodarone Drug Evaluation (the CASCADE study). Am J Cardiol 1991; 67(7): 578–84.

Pacifico A, Hohnloser SH, Williams JH, et al. Prevention of implantable-defibrillator shocks by treatment with sotalol. d, l-Sotalol Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Study Group. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1855–62.

Kuhlkamp V, Mewis C, Mermi J, et al. Suppression of sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias: a comparison of d, l-sotalol with no antiarrhythmic drug treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 33: 46–52.

Singer I, Al-Khalidi H, Niazi I, et al. Azimilide decreases recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43: 39–43.

Dorian P, Borggrefe M, Al-Khalidi HR, et al. Placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of azimilide for prevention of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Circulation 2004; 110: 3646–54.

Kou WH, Kirsh MM, Bolling SF, et al. Effect of antiarrhythmic drug therapy on the incidence of shocks in patients who receive an implantable cardioverter defibrillator after a single episode of sustained ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1991; 14: 1586–92.

Huang SK, Tan de Guzman WL, Chenarides JG, et al. Effects of long-term amiodarone therapy on the defibrillation threshold and the rate of shocks of the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Am Heart J 1991; 122: 720–7.

Wolbrette DL. Risk of proarrhythmia with class III antiarrhythmic agents: sex-based differences and other issues. Am J Cardiol 2003; 91(6A): 39D–44D.

O’Toole M, O’Neill G, Kluger J, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral dofetilide in patients with an implanted defibrillator: a multicenter study [abstract]. Circulation 1999; 100: 1–794.

Kowey PR, Singh B. Dronedarone in patients with implantable defibrillators: presented in a late breaking clinical trials session at Heart Rhythm 2004. 25th Annual Scientific Sessions; 2004 May 19–22; San Francisco (CA).

Connolly SJ, Hohnloser S, Dorian P, et al. Optimal Pharmacological Therapy in Implantable Cardioverter defibrillator patients (OPTIC) trial. Program and abstracts of the American College of Cardiology Annual Scientific Session; 2005 Mar 6–9; Orlando, (FL) [online]. Available from URL: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/501652 [Accessed 2005 Sep 15].

Movsowitz C, Marchlinski FE. Interactions between implantable cardioverterdefibrillators and class III agents. Am J Cardiol 1998; 82: 411–81.

Epstein AE, Ellenbogen KA, Kirk KA, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with high defibrillation thresholds: a multicenter study. Circulation 1992; 86: 1206–16.

Jung W, Manz M, Pizzulli L, et al. Effects of chronic amiodarone therapy on defibrillation threshold. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70: 1023–7.

Kuhlkamp V, Mewis C, Suchalla R, et al. Effect of amiodarone and sotalol on the defibrillation threshold in comparison to patients without antiarrhythmic drug treatment. Int J Cardiol 1999; 69: 271–9.

Waldecker B, Brugada P, Zehender M, et al. Importance of modes of electrical termination of ventricular tachycardia for the selection of implantable antitachycardia devices. Am J Cardiol 1986; 57: 150–5.

Santini M, Pandozi C, Ricci R. Combining antiarrhythmic drugs and implantable devices therapy: benefits and outcome. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2000; 4 Suppl. 1: 65–8.

Bansch D, Castrucci M, Bocker D, et al. Ventricular tachycardia above the initially programmed tachycardia detection interval in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: incidence, prediction and significance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36: 557–65.

Foody JM, Farrell MH, Krumholz HM. Beta-blocker therapy in heart failure: scientific review. JAMA 2002 Feb 20; 287(7): 883–9.

Acknowledgments

Dr Andreas Bollmann was supported by the Max Kade Foundation, Inc., New York, NY, USA. He serves as consultant to Sanofi-Aventis, Frankfurt, Germany.

Dr Daniela Husser was supported by a NBL-3 travel grant from the University Hospital Magdeburg, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bollmann, A., Husser, D. & Cannom, D.S. Antiarrhythmic Drugs in Patients with Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 5, 371–378 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00129784-200505060-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00129784-200505060-00004