Summary

Until 1986 to 1987, the estimation of patient compliance with prescribed drug regimens in ambulatory care relied on methods that were biased either by their subjectivity or by the improvement in compliance that commonly occurs during the day or two prior to a scheduled examination, so called ‘white-coat compliance’.

In 1986 to 1987, 2 objective methods were developed: electronic monitoring and low-dose, slow-turnover chemical markers (digoxin or phenobarbital [phenobarbitone]) incorporated into dosage forms. While neither method is without limitations, both have enabled major advances in the understanding of patients’ compliance with dosage regimens and, thus, the spectrum of drug exposure in ambulatory care. The new methods have also triggered not only a revival of interest in patient compliance and its determinants, but also new statistical approaches to interpreting the clinical correlates of widely variable drug administration, and thus drug exposure, in drug trials.

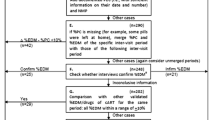

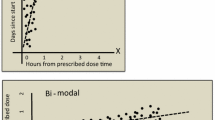

The marker methods prove dose ingestion during the 3 to 7 days prior to blood sampling, but do not reveal the timing of doses. The electronic monitoring methods, i.e. time and date-stamping microcircuitry incorporated into drug packages, provide a continuous record of timing of presumptive doses throughout periods of many months, but do not prove dose ingestion. The electronic record has been judged robust enough to detect certain types of investigator fraud, and to support modelling projections of the complete time course of the plasma drug concentration during a trial.

Both marker and electronic methods show that the predominant errors are those of omission, i.e. delays or omissions of scheduled doses. Patient interviews, diaries, and counts of returned, untaken doses have been shown by both marker and electronic monitoring methods to consistently and substantially to overestimate compliance. Monitoring of plasma drug concentrations also overestimates compliance, because white-coat compliance is prevalent, and the pharmacokinetic turnover of most drugs is rapid enough that measured concentrations of drug in plasma reflect only drug administration during the period of white-coat compliance.

Thus, compliance is a great deal poorer in clinical trials than has been revealed by the older methods. The long-standing underestimation of poor compliance in drug trials has many implications for the interpretation of drug trials, for optimal dose estimation, for the interpretation of failed drug therapy, and for accurate labelling of prescription drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bond WS, Hussar DA. Detection methods and strategies for improving medication compliance. Am J Hosp Pharm 1991; 48: 1978–88

Vander Stichele R. Measurement of patient compliance and the interpretation of randomized clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1991; 41: 27–35

Urquhart J. Real-time compliance monitoring in clinical trials: methods, early results, prospects. In: Hindmarch I, Stonier P, editors. Human psychopharmacology, Vol. III. Chichester (UK): John Wiley, 1990: 129–47

Kruse W. Patient compliance with drug treatment — new perspectives on an old problem. Clin Investig 1992; 70: 163–6

Pullar T, Feely M. Problems of compliance with drug treatment: new solutions? Pharm J 1990; 245: 213–5

Mäenpää H, Javela K, Pikkarainen J, et al. Minimal doses of digoxin: a new marker for compliance to medication. Eur Heart J 1987; 8 Suppl. I: 31–7

Feely M, Cooke J, Price D, et al. Low-dose phenobarbitone as an indicator of compliance with drug therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1987; 24: 77–83

Glover F. Dispenser for pharmaceuticals having patient compliance monitor apparatus. US Patent 4,034,757, July 12, 1977

Kass MA, Meltzer D, Gordon M. A miniature compliance monitor for ophthalmology. Arch Ophthalmol 1984; 102: 1550

Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, et al. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. JAMA 1989; 261: 3273–7

Eisen SA, Woodward RS, Miller D, et al. The effect of medication compliance on the control of hypertension. J Gen Intern Med 1987; 2: 298–305

Rubio A, Cox C, Weintraub M. Prediction of diltiazem plasma concentration curves from limited measurements using compliance data. Clin Pharmacokinet 1992; 22: 238–46

Weber E. Compliance: Neue Meßmethod mit MEMS. Med Mo Pharm 1988; 9(11): 308–9

Kruse W, Weber E. Dynamics of drug regimen compliance — its assessment by microprocessor-based monitoring. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1990; 38: 561–5

Urquhart J. Noncompliance: the ultimate absorption barrier. In: Prescott LF, Nimmo WS, editors. Novel drug delivery and its therapeutic applications. Chichester (UK): John Wiley, 1989: 127–37

Efron B, Feldman D. Compliance as an explanatory variable in clinical trials. J Am Stat Assoc 1991; 86(413): 7–17

Sheiner LB. The intellectual health of clinical drug evaluation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1991; 50: 4–9

Urquhart J, Chevalley C. Impact of unrecognized dosing errors on the cost and effectiveness of pharmaceuticals. Drug Info J 1988; 22: 363–78

Urquhart J. Time to take our medicines, seriously. Pharm. Weekbl Sci 1992; 127: 769–76

Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance and capricious compliance. In: Lasagna L, editor. Patient compliance. New York: Futura, 1976: 39–47

Dirks JF, Kinsman RA. Nondichotomous patterns of medication usage: the yes-no fallacy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1982; 31: 413–7

Waterhouse DM, Calzone KA, Mele C, et al. Adherence to oral tamoxifen: a comparison of patient self-report, pill counts, and microelectronic monitoring. J Clin Oncol 1993; 11: 1189–97

Didlake RH, Dreyfus K, Kerman RH, et al. Patient noncompliance: a major cause of late graft failure in cyclosporinetreated renal transplants. Transplant Proc 1988; 20; Suppl. 3: 63–9

Rovelli M, Palmeri D, Vossler E, et al. Noncompliance in organ transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 1989; 21(1): 833–4

Kass MA, Gordon M, Meltzer DW. Can ophthalmologists correctly identify patients defaulting from pilocarpine therapy? Am J Ophthalmol 1986; 101: 524–30

Cramer JA, Scheyer RD, Mattson RH. Compliance declines between clinic visits. Arch Int Med 1990; 150: 1509–10

Feinstein AR. On white-coat effects and the electronic monitoring of compliance. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150: 1377–8

Medication regimens: causes of noncompliance. Washington DC: Office of the Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services, June 1990

Urquhart J. Patient compliance as an explanatory variable in four selected cardiovascular studies. In: Cramer JA, Spilker B, editors. Compliance in medical practice and clinical trials. New York: Raven Press, 1991: 301–22

Urquhart J. Partial compliance in cardiovascular disease: risk implications. Br J Clin Pract 1994; Suppl 73: 2–12

Meredith PA, Elliott HL. Therapeutic coverage: reducing the risks of partial compliance. Br J Clin Pract 1994; Suppl 73: 13–7

Psaty BM, Koepsell TD, Wagner EH, et al. The relative risk of incident coronary heart disease associated with recently stopping the use of beta blockers. JAMA 1990; 263: 1653–7

Anon. Long-term use of beta blockers: the need for sustained compliance. WHO Drug Info 1990; 4(2): 52–3

Pullar T, Kumar S, Tindall H, et al. Time to stop counting the tablets? Clin Pharmacol Ther 1989; 46: 163–8

Rudd P, Byyny RL, Zachary V, et al. The natural history of medication compliance in a drug trial: limitations of pill counts. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1989; 46: 169–76

Guerrero D, Rudd P, Bryant-Kosling C, et al. Antihypertensive medication-taking. Investigation of a simple regimen. Am J Hypertens 1993; 6: 586–92

Kruse W, Nikolaus T, Rampmaier J, et al. Actual versus prescribed timing of lovastatin doses assessed by electronic compliance monitoring. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 44: 211–15

Meier P. Discussion. J Am Stat Assoc 1991; 86(413): 19–22

Lee YJ, Ellenberg JH, Hirta DG, et al. Analysis of clinical trials by treatment actually received: is it really an option. Stat Med 1991; 10: 1595–605

The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results: (I) Reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease; (II) The relationship of reduction in incidence or coronary heart disease to cholesterol lowering. JAMA 1984; 251: 351–74

Questran (cholestyramine). Physicians’ Desk Reference. Oradell (NJ): Medical Economics, 1994: 642–3

Lasagna L, Hutt PB. Health care, research, and regulatory impact of noncompliance. In: Cramer JA, Spilker B, editors. Compliance in medical practice and clinical trials. New York: Raven Press, 1991: 393–403

Compliance. Munich, Germany: 1990, Infratest AG.

Kruse W, Rampmaier J, Ullrich G, Weber E. Patterns of drug compliance with medication to be taken once and twice daily assessed by continuous electronic monitoring in primary care. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. In press

McKenney JM, Slining JM, Hendersen RH, et al. The effect of clinical pharmacy services on patients with essential hypertension. Circulation 1973; 48: 1104–11

Dickey FF, Mattar ME, Chudzik GM. Pharmacist counseling increases drug regimen compliance. J Am Hosp Assoc 1975; 49: 85–8

Inui TS, Yourtree EL, Williamson JW. Improved outcomes in hypertension after physician tutorials: a controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1976; 84: 646–51

Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Gibson ES, et al. Improvement of medication compliance in uncontrolled hypertension. Lancet 1976; 1: 1265–8

Cable GL, Schneider PJ. Experiences with the compliance clinic: assessment of the effect. Contemp Pharm Pract 1982; 5: 38–44

Foote A, Erfurt JC. Hypertension control at the work site: comparison of screening and referral alone, referral and follow-up, and on-site treatment. N Engl J Med 1983; 308: 809–13

Bond CA, Monson R. Sustained improvement in drug documentation, compliance, and disease control. Arch Intern Med 1984; 144: 1159–62

Hammarlund ER, Ostrum JR, Kethley AJ. The effects of drugs counseling and other educational strategies on drug utilization of the elderly. Med Care 1985; 23: 165–70

Leirer VO, Morrow DG, Pariante GM, et al. Elders’ nonadherence, its assessment, and computer assisted instruction for medication recall training. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988; 36: 877–84

Snider DE Jr, Hutton MD. Improving patient compliance in tuberculosis treatment programs. Center for Diseases Control, Atlanta, Georgia: US Dept of Health & Human Services. [Revised] February 1989

Urquhart J. Cost-benefit assessment of patient education. In: Can patient education really make a difference? Proc USP Open Conference; 1992 Sept 21–23: Rockville (Md): United States Pharmacopeia, 1993: 37–50

Levy G. A pharmacokinetic perspective on medicament non-compliance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1993; 54: 242–4

Joyce CRB. Patient co-operation and the sensitivity of clinical trials. J Chron Dis 1962; 15: 1025–36

Wood HF, Feinstein AR, Taranta A, et al. Rheumatic fever in children and adolescents: a long-term epidemiologic study of subsequent prophylaxis, streptococcal infections, and clinical sequelae. III. Comparative effectiveness of three prophylaxis regimens in preventing streptococcal infections and rheumatic recurrences. Ann Int Med 1964; 60 Suppl. 5: 31–46

Kruse WH-H. Compliance with treatment of hyperlipoproteinemia in medical practice and clinical trials. In: Cramer JA, Spilker B, editors. Compliance in medical practice and clinical trials. New York: Raven Press, 1991: 175–86

Morris SE, Groom GV, Cameron ED, et al. Studies on low dose oral contraceptives: plasma hormone changes in relation to deliberate pill (‘MICROGYNON 30’) omission. Contraception 1979; 20: 61–9

Chowdry V, Joshi UM, Gopalkrishna K, et al. ‘Escape’ ovulation in women due to the missing of low dose combination oral contraceptive pills. Contraception 1980; 22: 241–7

Wang E, Shi S, Cekan SZ, et al. Hormonal consequences of ‘missing the pill’. Contraception 1982; 26: 545–66

Landgren B-M, Diczfalusy E. Hormonal consequences of missing the pill during the first two days of three consecutive artificial cycles. Contraception 1984; 29: 437–46

Smith SK, Kirkman RJE, Arce BB, et al. The effect of deliberate omission of TRINORDIOL® or MICROGYNON® on the hypothalamo-pituitary-ovarian axis. Contraception 1986; 34: 513–22

Johnson BF, Whelton A, McMahon FG. Betaxolol vs atenolol in hypertension: a comparison of efficacy, duration of response, and effects of withdrawal [abstract 1429]. Am J Hypertens 1990; 3(5): Part II, 121A

Uretsky BF, Young JB, Shahidi FE, et al. Randomized study assessing the effect of digoxin withdrawal in patients with mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure: results of the PROVED study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993; 22: 955–62

Packer M, Gheorghiade M, Young JB, et al. Withdrawal of digoxin from patients with chronic heart failure treated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1–7

Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Influence of adherence to treatment and response of cholesterol on mortality in the coronary drug project. N Engl J Med 1980; 303: 1038–41

Rubin D. Comment: dose-response estimates. J Am Stat Assoc 1991; 86(413): 22–4

Goetghebeur EJT, Pocock SJ. Statistical issues in allowing for noncompliance and withdrawal. Drug Info J 1993; 27: 837–45

Coats AJS, Adamopoulos S, Meyer TE, et al. Effects of physical training in chronic heart failure. Lancet 1990; 335: 63–6

Phillips GD, Harrison NK, Cummin ARC, et al. New method for measuring compliance with long term oxygen treatment. BMJ 1994; 308: 1544–5

Fielder AR, Auld R, Irwin M, et al. Compliance monitoring in amblyopia therapy. Lancet 1994; 343: 547

Peck CC, Barr WH, Benet LZ, et al. Opportunities for integration of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicokinetics in rational drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1992; 51: 465–73

Wood HF, Simpson R, Feinstein AR, et al. Rheumatic fever in children and adolescents: a long-term epidemiologic study of subsequent prophylaxis, streptococcal infections, and clinical sequelae. I. Description of the investigative techniques and of the population studied. Ann Int Med 1964; 60 Suppl. 5: 6–17

Gavrin JB, Tursky E, Albam B, et al. Rheumatic fever in children and adolescents: a long-term epidemiologic study of subsequent prophylaxis, streptococcal infections, and clinical sequelae. II. Maintenance and preservation of the population. Ann Int Med 1964; 60 Suppl. 5: 18–30

Urquhart J. Ascertaining how much compliance is enough with outpatient antibiotic regimens. Postgrad Med J 1992; 68 Suppl. 3: S49–59

Gordis L. General concepts for use of markers in clinical trials. Controlled Clin Trials 1984; 5: 481–7

Manninen V, Elo MO, Frick H, et al. Lipid alternations and decline in the incidence of coronary heart disease in the Helsinki Heart Study. JAMA 1988; 260: 641–51

Mäenpää H, Manninen V, Heinonen OP. Comparison of the digoxin marker with capsule counting and compliance questionnaire methods for measuring compliance to medication in a clinical trial. Eur Heart J 1987; 8 Suppl. I: 39–43

Kumar S, Haigh JRM, Rhodes LE, et al. Poor compliance is a major factor in unstable outpatient control of anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost 1989; 62: 729–32

Pullar T, Peaker S, Martin MFR, et al. The use of a pharmacological indicator to investigate compliance in patients with a poor response to antirheumatic therapy. Br J Rheumatol 1988; 27: 381–4

Penn ND, Speaker S, Griffiths AP, et al. Use of a pharmacological indicator to monitor compliance with thyroxine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1988; 35: 327–9

Pullar T, Birtwell AJ, Wiles PG, et al. Use of a pharmacologic indicator to compare compliance with tablets prescribed once, twice, or three times daily. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1988; 44: 540–5

Kass MA, Zimmerman T, Yablonski M, et al. Compliance to pilocarpine therapy [ARVO abstract 2]. Invest Ophthalmol 1977;Suppl. 108

Averbuch M, Weintraub M, Pollack DJ. Compliance assessment in clinical trials: the MEMS device. J Clin Res Pharmacoepidemiol 1990; 4: 199–204

Potter LS. Oral contraceptive compliance and its role in the effectiveness of the method. In: Cramer JA, Spilker B, editors. Compliance in medical practice and clinical trials. New York: Raven Press, 1991: 195–207

Tashkin DP, Rand C, Nides M, et al. A nebulizer chronolog to monitor compliance with inhaler use. Am J Med 1991; 91 Suppl. 4A: 33S–36S

Powers-Cramer ML. Use of MEMS® as a source document in clinical trials. Abstracts of the Drug Information Association Workshop on Clinical Data Management: New Techniques, New Technologies. 1990 Sept 24–6; Philadelphia.

Petzinna D. Miscellaneous useful methods to detect fraud. Paper presented at Drug Information Association conference ‘Detection of Fraud’, Sept 27–8, 1993, Paris, France.

Métry J-M. How technology may help. Paper presented at Drug Information Association conference ‘Detection of Fraud’, Sept 27–8, 1993, Paris, France.

Vander Stichele RH, Thomson M, Verkoelen K, et al. Measuring patient compliance with electronic monitoring: lisinopril versus atenolol in essential hypertension. Post-marketing Surveillance 1992; 6: 77–90

Harter JG, Peck CC. Chronobiology: suggestions for integrating it into drug development. Ann NY Acad Sci 1991; 618: 563–71

Hasford J. Biometric issues in measuring and analyzing partial compliance in clinical trials. In: Cramer JA, Spilker B, editors. Compliance in medical practice and clinical trials. New York: Raven Press, 1991: 265–81

Temple R. Dose-response and registration of new drugs. In: Lasagna L, Erill S, Naranjo CA, editors. Dose-response relationships in clinical pharmacology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1989: 145–67

Lasagna L. Pharmacometry in man: the state of the art. In: Lasagna L, Erill S, Naranjo CA, editors. Dose-response Relationships in Clinical Pharmacology. Esteve Foundation Symposia, vol 3. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, 1989: 1–7

Anon. Patient compliance in therapeutic trials [editorial]. Lancet 1991; 337: 823–4

Meredith PA, Elliott HL. Therapeutic coverage: reducing the risks of partial compliance. Br J Clin Practice 1994; Suppl 73: 13–17

Matsui D, Hermann C, Braudo M, et al. Clinical use of the Medication Event Monitoring System: A new window into pediatric compliance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1992; 52: 102–3

Paladino JA, Sperry HE, Backes JM, et al. Clinical and economic evaluation of oral ciprofloxacin after an abbreviated course of intravenous antibiotics. Am J Med 1991; 91: 462–70

Matsuyama JR, Mason BJ, Jue SG. Pharmacists’ interventions using an electronic medication-event monitoring device’s adherence data versus pill counts. Ann Pharmacother 1993; 27: 851–5

Deming WE. Out of the crisis. Cambridge (MA): MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study, 1982

van den Besselaar AMHP, van der Meer FJM, Gerrits-Drabbe CW. Therapeutic control of oral anticoagulant treatment in the Netherlands. Am J Clin Path 1988; 90: 685–90

van der Meer J, Hillege HL, Kootstra GJ, et al. Prevention of one-year vein-graft occlusion after aortocoronary-bypass surgery: a comparison of low-dose aspirin, low-dose aspirin plus dipyridamole, and oral anticoagulants. Lancet 1993; 342: 257–64

Guillebaud J. Any questions? BMJ 1993; 307: 617

How to take the pill. In: Physicians’ desk reference. Oradell (NJ): Medical Economics, 1994: 1673–4

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Urquhart, J. Role of Patient Compliance in Clinical Pharmacokinetics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 27, 202–215 (1994). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199427030-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199427030-00004