Abstract

Poorly soluble drugs are increasingly formulated into supersaturating drug delivery systems which may precipitate during oral delivery. The link between in vitro drug concentration profiles and oral bioavailability is under intense investigation. The objective of the present work was to develop closed-form analytical solutions that relate in vitro concentration profiles to the amount of drug absorbed using several alternate assumptions and only six parameters. Three parameters define the key features of the in vitro drug concentration-time profile. An additional three parameters focus on physiological parameters. Absorption models were developed based on alternate assumptions; the drug concentration in the intestinal fluid: (1) peaks at the same time and concentration as in vitro, (2) peaks at the same time as in vitro, or (3) reaches the same peak concentration as in vitro. The three assumptions provide very different calculated values of bioavailability. Using Case 2 assumptions, bioavailability enhancement was found to be less than proportional to in silico examples of dissolution enhancement. Case 3 assumptions lead to bioavailability enhancements that are more than proportional to dissolution enhancements. Using Case 1 predicts drug absorption amounts that fall in between Case 2 and 3. The equations developed based on the alternate assumptions can be used to quickly evaluate the potential improvement in bioavailability due to intentional alteration of the in vitro drug concentration vs. time curve by reformulation. These equations may be useful in making decisions as to whether reformulation is expected to provide sufficient bioavailability enhancement to justify the effort.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) was designed to group compounds into one of four categories based on both solubility and permeation rate, in order to accelerate the drug development process (1). The majority of compounds currently in development are classified as BCS II, highly permeable and poorly soluble, requiring formulation strategies to increase solubility and dissolution rates (2).

One approach to increase solubility is to formulate the BCS II compounds in the amorphous state, where the amorphous solid produces a highly supersaturated solution. Once a maximum concentration is reached, precipitation can reduce the concentration to at/near crystalline solubility (3). It is often assumed that the higher the amorphous peak concentration, the higher the bioavailability. However, a higher degree of supersaturation does not always lead to increased absorption, indicating that this parameter alone is not a suitable predictor of bioavailability for potential amorphous formulation (4,5).

Over the past 25 years, mathematical models have been developed to estimate in vivo drug absorption from in vitro drug concentration-time data (6–16). These biopharmaceutical models base their prediction of drug absorption on physicochemical properties of the drug (solubility, pKa, physical state), physiological properties (absorption rate constant, local pH, transit time), and dosage form (17). Current models range from simple equations to complex computer simulations. For instance, a simple model may use as few as four parameters to estimate drug absorption (e.g., the maximum absorbable dose (MAD) model considers only the absorption rate constant and solubility) (18,19), whereas computer models (e.g., GastroPlus™, Stella®, Intellipharm®, and Simcyp®) may utilize over 20 parameters (7,17,19–24).

While there are several biopharmaceutical models in the literature that are reported to be capable of handling precipitating drug, most require a large number of parameters to reliably predict in vivo absorption (2,20). To date, there are no simple equations like the MAD in the literature that take into account the effect of precipitation in the intestinal lumen on bioavailability. It would be useful to have a model that has the capability of estimating the magnitude of the effect of formulation changes on oral drug absorption of amorphous compounds, based on a limited number of in vitro parameters in order to speed the screening of promising BCS II drugs during development (2).

The objective of the current work was to develop sparsely parameterized mathematical models relating in vitro drug concentration-time profile (often referred to as a dissolution profile) of the amorphous form of a model drug to an estimate of in vivo drug concentration-time profile. To obtain in vivo luminal concentration-time profiles from in vitro dissolution profiles, precipitation was assumed to be dependent on time or dependent-on-concentration. Closed-form equations describing absorption were derived based on each set of assumptions.

MODEL DEVELOPMENT

Parameterization of In Vitro Drug Concentration-Time Profiles

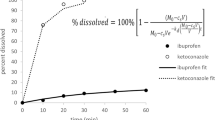

During in vitro drug dissolution from amorphous powders and formulations, precipitation often occurs after maximum supersaturation is reached (Fig. 1) (4). A supersaturation ratio is defined here as the maximum drug concentration over the plateau concentration. Similar ratios of maximum supersaturation have been used as predictors of the oral bioavailability enhancement of the amorphous form, with variable success (5,25).

Examples of in vitro concentration-time profiles obtained from dissolution of excess amorphous solid powder in water in a USP type 2 dissolution apparatus at 25°C. Adapted from reference (34)

Each in vitro drug concentration-time profile of an amorphous form differs in concentration at peak, duration of the peak, peak shape, and plateau concentration (Fig. 1). Previous investigators have modeled the supersaturation in vitro dissolution curve (26,27). However, our goal of obtaining a closed-form analytical solution for the bioavailability of an amorphous formulation demands a more parsimonious parameterization of the in vitro curves. Here, we seek to capture the main features of each curve with a minimum number of parameters, allowing rapid characterization. Of course, the use of biological relevant medium and volumes will provide better input (28–33). To be sure, there is some loss in accuracy when a minimum number of parameters are used to characterize a wide variety of peak shapes. The simplicity and time-savings gained from using few parameters on which to base an estimate of bioavailability is thought to outweigh any real or suspected accuracy obtained from describing the experimental dissolution curve in greater detail.

It would initially seem that characterizing the in vitro concentration vs. time profile using the area under the curve (AUC) would be the simplest and most direct approach. When there is negligible depletion of drug from intestinal fluids due to low absorption rate constant, as is the case for BCS IV compounds, the in vivo concentration vs. time profile mirrors in vitro. The AUC of the in vivo concentration vs. time profile can be determined from the in vitro curve when using biologically relevant medium and volumes. The total amount of drug absorbed is simply the product of in vivo AUC, intestinal fluid volume, and absorption rate constant. However, the main focus of the proposed model is to estimate the amount of drug absorbed for BCS II compounds. BCS II drugs have significant absorption rate constants which leads to significant depletion of drug from gastrointestinal fluid, so that the total amount of drug cannot be directly calculated from AUC without underestimating the amount of drug absorbed.

Several other approaches to characterizing the in vitro drug concentration-time curves were considered. One approach is to identify the maximum concentration (C g m),Footnote 1 plateau drug concentration following the peak (C g p), the time to the maximum concentration (T g m), and time to reach plateau concentration (T g p) directly from the in vitro drug concentration profile (Fig. 2a). This approach is simple and uses only four parameters to characterize the peak as a general Euclidian triangle. However, this approach underestimates the area under the experimental peak in the dissolution profile (by 14, 39, and 42%, respectively, for in vitro profiles shown in Fig. 1). Additionally, the time to reach the plateau is not easily identified, particularly for nonlinearly decline to the plateau concentration.

Potential ways to characterize the key aspects of an in vitro drug concentration-time profile for a supersaturating drug: a four parameters: peak concentration, time to peak, plateau concentration, and time to plateau; b three parameters using an isosceles triangular peak shape: peak concentration, time to peak, and plateau concentration; c three parameters using an isosceles triangular peak shape: peak concentration, full width at half maximum of the peak, and plateau concentration; d three parameters: peak concentration, peak duration, and plateau concentration using a rectangular approximation; and e four parameters: lag time, peak concentration, peak duration, and plateau concentration using a rectangular approximation

A second approach is to approximate the peak as an isosceles triangle (Fig. 2b) where the maximum concentration (C g m), the plateau concentration (C g p), and the time to peak (T g m) are identified directly from the in vitro drug concentration profile. Using this approach, the time to reach the plateau concentration (T g p) can be calculated from the relationship between two similar triangles. The use of isosceles triangles provides simplicity in the development of the model and in the resulting equations used to estimate the bioavailability. However, this approach more severely underestimates the area under the experimental peak than does the first approach.

A third approach combines the advantages of the first two. The maximum drug concentration (C g m) and the plateau drug concentration (C g p) following the peak are identified directly from the in vitro drug concentration profile. However, in this approach, (T g m) and (T g p) are not determined directly from inspection of time points on the profile. Rather, the width of the peak is characterized by its full width at half maximum.

In order to obtain (T g m) and (T g p), first, the concentration at half the height of the peak (C HM) that extends beyond the lower plateau concentration (C g p) is determined (Eq. 1).

At the half maximum concentration (C HM), the width of the peak (T HM) is identified by subtracting the time to reach (C HM) initially (T a) from the time (T b) at which the concentration declines to C HM (Fig. 2c). The full width at half maximum (T HM) of the experimental drug concentration time profile is a measure of duration of the peak and is used to define the length of the base of the isosceles triangle corresponding to the drug peak. There are several advantages of this approach. First, it requires only three parameters (C g m, C g p, and T HM) to characterize the in vitro curve.Footnote 2 The value of T g m can be calculated using similar triangles (Eq. 2, Fig. 3) from the two concentrations, C g m and C g p, and the full width at half maximum (T HM).

As shown in Fig. 3, the time to reach the plateau concentration (T g p) can be calculated from T g m, C g m, and C g p (Eq. 3) rather than identified directly from the experimental curve.

Using this heuristic approach, the area under the three-parameter approximation (C g m, C g p, and T HM) of the dissolution curve differs from the area under the experimental dissolution profile by only 9% for the case of indomethacin, 12% for the case of hydrochlorothiazide, and 26% for the case of danazol (Fig. 1). Several other drug dissolution profiles (34) were evaluated and the difference in area under the curve is 14 ± 7%. It should be noted that the time to peak using the isosceles triangular approximation will not always equal the time to peak concentration from the in vitro drug concentration-time profile. However, the simplicity in the derivation of bioavailability equations using the isosceles triangle to approximate the experimental data is thought to outweigh the loss in fidelity in the description of all aspects of the peak shape.

Indeed, there are a myriad of other ways to approximate the variety of shapes of in vitro concentration-time profiles. For some curves, a peak drug concentration is reached quite rapidly and maintained for a period of time until very rapid precipitation occurs, resulting in a concentration-time profile that may be better parameterized using a rectangular approximation as illustrated in Fig. 2d. However, with this approach another parameter, a “lag” time, or the time to reach in vitro peak concentration, C g m, is often needed (Fig. 2e). For some profiles (e.g., hydrochlorothiazide and danazol in Fig. 1), a rectangular shape would overestimate the area under the curve. Using a rectangular approximation without the “lag” time (Fig. 2d) would allow peak approximation using just three parameters, as was achieved using the isosceles triangular approximation (Fig. 3). However, the area under the curve is often more severely overestimated than without the use of a “lag” time parameter.

Another approach would be to characterize in vitro profile by either the triangle or rectangular approximation, whichever fits best. However, this would eliminate the ability to use a single system to compare drug concentration-time curves of a single drug from different formulations. Later in the text, the isosceles triangular approximation is compared to an equivalent rectangular approximation in order to identify any bias imposed by the use of the triangular approximation.

Relationship Between In Vitro Drug Concentration Profile and Drug Concentration in Intestinal Fluid

A one-tank model (9) is used to calculate the amount of drug absorbed from the three-parameter approximation of the in vitro concentration profile. Originally, the one-tank model was used to describe dissolution-limited absorption, with no precipitation. Here, it is extended to include precipitation.

USP Apparatus II has been traditionally used to assess in vitro drug dissolution, where a quantity of drug powder (X g o) is dispersed in a medium of a constant volume (V g). For supersaturating drug forms, such as the amorphous form considered here, the amount of excess solid (X g e(t)) and the amount of drug in solution (X g s(t)) change with time as a result of dissolution and precipitation. The total amount of drug in the vessel (X g o) remains constant (Fig. 4a and Eq. 4).

Illustration a of the mass balance of a supersaturating drug during in vitro dissolution in USP type II apparatus with reference to the terminology used in the mathematical model and b of the mass balance of a supersaturating drug during dissolution in vivo in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract using terminology used in the mathematical model

This process is more complicated in vivo (35). For the simplest case where the dose administered in vivo (X l o)Footnote 3 is introduced directly into the small intestines (by, for example, an enteric-coated dosage form), many of the processes in vivo (Fig. 4b) and in vitro (Fig. 4a) are similar, where the amount of drug in solution (X l s(t)) and amount of excess solid (X l e(t)) vary with time and depend on the volume available for dissolution in the luminal fluid (V l).

However, in vivo, as dissolution and precipitation are occurring, absorption is also taking place, such that there is depletion of the dose (X l o) from the intestinal lumen. The total amount of drug in vivo (X l o) is then equal to the amount of drug in solution (X l s(t)), amount of drug in the solid (X l e(t)) as well as amount absorbed (X l a(t)) (Eq. 5).

There are two major differences between the in vitro and in vivo systems. Due to depletion of dissolved drug via absorption, the concentration of drug in solution (X l s(t)/V l) in the small intestine will be lower than the concentration of drug during in vitro dissolution (X l s(t)/V g) (36). Furthermore, the in vitro fluid volume (V g) is traditionally much greater than small intestinal fluid volume (V l). Using USP Apparatus (type 1 or 2), the volume ranges from 250 mL to 1 L (32), while the volume of the small intestinal fluid has been reported to be only 45 to 320 mL (37). The lower in vivo volume can result in a significantly lower amount of drug in solution in vivo (22). This is particularly important for amorphous formulations where the degree of supersaturation and excess remaining solid can influence the time course of precipitation (3).

Precipitation is a function of both concentration and time; the peak concentration and its duration depend on the drug, drug form, dose, and formulation components (the exact dependence of which is the focus of intense current investigation) (5,28,29,38–43). If both the peak drug concentration and duration of that peak in vivo were equal to the values determined from the in vitro dissolution profile (Fig. 5a), bioavailability would be proportional to the area under the in vitro concentration-time curve, adjusting for volume, of course.

Comparison of the isosceles triangular approximation of an in vitro dissolution curve of a supersaturating drug with three different sets of assumptions regarding the relationship between in vitro and in vivo dissolution behavior. C g s(t) is the drug concentration at a given time in in vitro dissolution medium. C l s(t) is the drug concentration at a given time in the small intestinal fluid and C l n(t) is the drug concentration in vivo in the absence of absorption. a Case 1 as described in the text, b Case 2 as described in the text, and c Case 3 as described in the text

Alternatively, assuming drug precipitation is dependent on time, absorption would deplete the concentration of dissolved drug resulting in a peak drug concentration in vivo that is lower than in vitro. In this case, the bioavailability would be less than proportional to the area under the in vitro dissolution curve. Using the three-parameter isosceles triangular approximation of the dissolution curve, this is equivalent to assuming precipitation occurs at the same time in the small intestine as determined in vitro (Fig. 5b).

In contrast, assuming drug precipitation is dependent-on-concentration, the drug concentration in vivo would eventually reach the same peak in vitro concentration. However, depletion due to absorption of drug from the small intestine would prolong the time to peak. The extended period of elevated drug concentration would result in greater absorption compared to that predicted from the in vitro dissolution area under the curve. Using the isosceles triangular approximation, this case is equivalent to in vivo precipitation occurring at the same concentration as observed in vitro (Fig. 5c).

It is not known with certainty whether the concentration profiles are the same in vitro and in vivo, or whether it is the in vivo peak drug concentration or the duration of the elevated concentration that corresponds better the in vitro dissolution profile. However, the drug concentration behavior in vivo is likely bracketed by assumptions (a) equivalent duration of the peak in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 5b) and (b) equal peak concentrations in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 5c). Potential bioavailability enhancement that could be achieved by formulation changes which alter the drug peak concentration and/or duration should be within these two extremes. Therefore, derivation of closed-form analytical equations based on these assumptions allows us to easily quantify the potential effects of precipitation on bioavailability of supersaturating drug delivery systems.

Three Cases for In Vivo Dissolution Behavior

Depending on the drug properties and the conditions in the small intestine, three cases based on the above assumptions can be explored using the isosceles triangular approximation of the in vitro dissolution.

For Case 1, the drug concentration in small intestinal fluid (C l s(t)) mirrors the in vitro drug concentration vs. time curve (C g s(t)). Using the three-parameters characterizing the in vitro curve, the peak drug concentration (C l m 1) in vivo occurs at the same time and concentration as seen in vitro (C g m) (Fig. 5a). This scenario is limited to drugs with low absorption rate constants, such as is the case for BCS IV compounds.

For Case 2, the duration of the elevated drug concentration in vivo corresponds to the in vitro dissolution behavior. Using the isosceles triangle approximation, the peak drug concentration in vivo (C l m 2) occurs at the same time (T l m 2 = T g m) in vitro, but due to absorption, the peak drug concentration in vivo (C l m 2) is lower than in vitro (C g m) (Fig. 5b). This scenario is more consistent with precipitation being a dependent-on-time phenomenon and is referred to below as the dependent-on-time precipitation case.

For Case 3, precipitation in vivo (C l m 3) occurs at the same concentration (C g m) as seen in vitro, but due to absorption, the time to reach peak concentration in vivo (T l m 3) occurs at a later time than in vitro (T g m) (Fig. 5c). This scenario is more consistent with precipitation being a dependent-on-concentration phenomenon and is referred to below as the dependent-on-concentration precipitation case.

Development of Mathematical Equations Describing Drug Absorption for Precipitating Drugs

The following conditions were specified to further simplify the model:

-

1.

Drug dissolution and absorption occur in the small intestine only.

-

2.

The small intestinal lumen can be considered a single mixing tank at a constant volume.

-

3.

Drug absorption is a first-order process with respect to concentration.

-

4.

Once drug precipitation is complete, drug concentration remains constant.Footnote 4

-

5.

There is excess solid drug remaining at the end of absorption.

-

6.

Drug precipitation is non-pH dependent.

A first-order absorption rate (k a) constant is used to relate the amount of drug in solution in vivo (X l s(t)) to the amount absorbed (Eq. 6)

where X l a(t) is the amount absorbed.

The amount of drug in solution in small intestinal fluid at any time (X l s(t)) is equal to its concentration (C l s(t)) times small intestinal fluid volume (V l). Equation 6 becomes:

Equation 7 can be applied to the isosceles triangular approximation of the dissolution curve to derive equations of the amount of drug absorbed, for each of the three cases described. The three-parameter approximation to the concentration profile has two discontinuities. For simplicity in the derivation of the amount of drug absorbed, the profile is divided into three phases (Fig. 5). Drug absorbed during each phase is calculated separately.

-

Phase i: The period between initial drug release and peak concentration

-

Phase ii: The time from peak drug concentration to the plateau concentration

-

Phase iii: The period over which the plateau concentration extends (where the drug in solution is in equilibrium with the solid drug)

The total amount of drug absorbed is the sum of drug absorbed during each phase. Equations describing the total amount of drug absorbed for each model assumption (i.e., Cases 1, 2, and 3) are presented below. Details of their deviation are found in Supplemental 1.

Case 1

In this simplest case, the concentration of drug in solution in vivo is equal to the concentration of drug in solution in vitro (C l s(t) = C g s(t)) at all times during small intestinal transit, 0 < t < T l r (Fig. 5a).Footnote 5 The total amount of drug absorbed (X l a(t)) can be determined from the in vitro dissolution profile (C g s(t)) using Eq. 7. Equation 8 describes the total amount of drug absorbed during all three phases for Case 1, \( {\left.{X}_{\mathrm{l}}{a}_1\right|}_0^{T_{\mathrm{l}}r} \), as illustrated in Fig. 5a.Footnote 6

This approach uses the three parameters obtained from the in vitro concentration-time profile: C g m, T g m, and C g p (Figs. 2c and 3; Eq. 2). Since the in vivo and in vitro drug concentration vs. time profiles are assumed to be equal for Case 1, the corresponding in vivo parameters equal those determined in vitro (i.e., C l m 1 = C g m, T l m 1 = T g m, C l p = C g p, and T l p 1 = T g p).Footnote 7

Case 2

The dependent-on-time precipitation case assumes the peak duration in vivo corresponds to the in vitro time to peak in the absence of absorption. Using the three-parameter approximation of the in vitro dissolution time profile, this assumption translates to the time to peak in vivo equaling the time to peak in vitro (T l m 2 = T g m), as shown in Fig. 5b. There are two equations (9a and 9b) for calculating the amount of drug absorbed (\( {\left.{X}_{\mathrm{l}}{a}_2\right|}_0^{T_{\mathrm{l}}r} \)) using Case 2 assumptions depending on the supersaturation ratio (\( \frac{C_{\mathrm{g}}m}{C_{\mathrm{g}}p} \)).

When \( \frac{C_{\mathrm{g}}m}{C_{\mathrm{g}}p}>\left({k}_{\mathrm{a}}\right)\left({T}_{\mathrm{g}}m\right) \) (i.e., the supersaturation ratio is sufficiently higher relative to the product of the k a and T g m). When T g m is prolonged or absorption is rapid, the peak concentration in vivo is far below in vitro, reducing the enhancement.

When \( \frac{C_{\mathrm{g}}m}{C_{\mathrm{g}}p}\le\ \left({k}_{\mathrm{a}}\right)\left({T}_{\mathrm{g}}m\right) \),

where

With depletion due to absorption, the in vivo concentration will be lower than the concentration in solution in vitro (C g s(t)), as shown in Fig. 5b. While the time to peak remains unchanged (T l m 2 = T g m) in Case 2, we note that the peak drug concentration in vivo (C l m 2) is lower than the peak concentration in vitro (C g m) (Eq. 10). As in Case 1, the plateau concentration in vivo (C l p) remains equal to that in vitro (C g p), i.e., C g p = C l p. However, the time to reach the plateau in vivo (T l p 2) is less than that observed in vitro (T g p) (Eq. 11), again due to absorption. The time to reach plateau concentration (T l p 2) is generally greater than T g m. However, when the supersaturation ratio (C g m/C g p) drops below the product of k a and T g m, then T l p 2 < T g m, eliminating phase ii. The total amount of drug absorbed is calculated from phases i and iii only (Eq. 9b).

Case 3

The dependent-on-concentration precipitation case assumes drug concentration reaches the same peak value in vivo as in vitro (C l m 3 = C g m). The total amount of drug absorbed during all three phases (\( {\left.{X}_{\mathrm{l}}{a}_3\right|}_0^{T_{\mathrm{l}}r} \)) is determined by Eq. 12a or 12b, depending on the time to peak (T l m 3) relative to small intestinal transit time (T l r).

When the time to peak is smaller than the small intestinal transit time (i.e., T l m 3 < T l r),

When the time to peak is equal or greater than the small intestinal transit time (i.e., T l m 3 ≥ T l r),

Where

In the absence of absorption, as in Case 1, the concentration of drug in solution in vivo (C l s(t)) would equal the concentration of drug in solution in vitro (C g s(t)). However, as in Case 2, absorption results in a depletion in drug concentration in solution in vivo (C l s(t)). Therefore, the peak drug concentration in vivo occurs at a later time (T l m 3) than the time derived from the in vitro profile (T g m), such that T l m 3 ≥ T g m (Eq. 13). When the value of T l m 3 is greater than the small intestinal transit time (T l r), phase i completely dominates the absorption profile (Eq. 12b).

In all three cases, the extent of drug absorption can be calculated from closed-form analytical equations. Only six parameters are required to obtain solutions, three of which are determined from in vitro concentration vs. time profiles. From these equations, the potential bioavailability enhancement that could be gained from reformulation efforts to modify supersaturation peak duration and/or concentration may be quantitatively explored a priori.

METHODOLOGY

The amount of drug absorbed using the assumptions corresponding to each case described above was calculated from Eqs. 8, 9a, 9b, 12a, and 12b for three drug constructs in a patient described by average physiological parameters. The value for small intestinal fluid volume (V l) is 70 mL and the transit time (T l r) is 180 min, which represent median values from the literature (22,37,44–46). The plateau concentration (C g p) was set to 10 μg/mL to reflect the low solubility values for many BCS II compounds, particularly those for which dissolution enhancement strategies, such as amorphization, are sought.

The values of the remaining three parameters—absorption rate constant (k a), peak drug concentration reached during in vitro dissolution performance evaluation (C g m), and the parameter reflecting drug concentration peak duration in vitro (T g m)—were explored over wide ranges. The k a values for BCS II and IV compounds were found to range from 0.0003 to 0.08 min−1(47). The ranges for both C g m and T g m values were chosen based on experimental data (34). A 3 × 6 × 5 full-factorial design for each case was utilized where k a was evaluated at three levels, 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 min−1; C g m ranged from 20 to 100 μg/mL in 20 μg/mL increments corresponding to maximum supersaturation ratio (C g m/C g p) from 2 to 10; and T g m was evaluated in 10 min increments from 10 to 60 min.

RESULTS

The mathematical models (Eqs. 8, 9a, 9b, 12a, and 12b) were developed to quickly evaluate the potential improvement in bioavailability due to intentional alteration of the in vitro drug concentration vs. time curve by reformulation. These equations may be useful in making decisions as to whether reformulation is expected to provide sufficient bioavailability enhancement to justify the effort.

The models were applied to drug constructs with a range of absorption rate constant. As will be shown below, the relationship between in vitro dissolution profile and bioavailability is dependent on k a. Therefore, the results for low, moderate, and high k a values are presented in separate sections. Within each section, the bioavailability enhancement gained by prolonging T g m and increasing C g m/C g p will be discussed in detail using the assumptions used in Cases 1, 2, and 3.

Drugs with a Low Absorption Rate Constant (k a = 0.001 min−1)

The absorption half-life corresponding to k a of 0.001 min−1 is nearly 12 h, which is 4 times the small intestinal transit time and 6–36 times the time period during which drug is in supersaturated state, ~2(T g m). The three plots (Fig. 6a, d, g) showing the amount of drug absorbed for each case are superimposable when the absorption rate constant is low, since there is negligible drug depletion from the intestinal lumen. Thus, for poorly permeable compounds, the simpler Case 1 equation (Eq. 8) provides the same prediction of the amount of drug absorbed as would the more complex equations for Cases 2 and 3 (Eqs. 9a, 9b, 12a, and 12b).

Amount of drug absorbed using the assumptions of Case 1 (a–c), Case 2 (d–f), and Case 3 (g–i), at three values of k a (0.001, 0.01, 0.1 min−1) for a range of T g m (10–60 min) and C g m/C g p (2–10). Note that the scale of the z-axis (total amount of drug absorbed) increases with k a value. For k a = 0.01 min−1 (a, d, g), the amount absorbed ranges from 0 to 0.6 mg; for k a = 0.01 min−1 (b, e, h), 0 to 6 mg; and for k a = 0.1 min−1 (c, f, i), 0 to 120 mg

For these poorly permeable compounds, an increase in peak duration (T g m) and/or peak height relative to the plateau (C g m/C g p) generally results in an increase in the total amount of drug absorbed. However, at lower peak concentrations, C g m/C g p = 2, sustaining the duration of the peak (i.e., increasing T g m from 10 to 60 min) does little to improve the amount of drug absorbed (i.e., less than 7% increaseFootnote 8). Similarly, when the peak concentration cannot be sustained (i.e., T g m = 10 min), there is only about a 40% improvement in the amount of drug absorbed when efforts are made to raise the in vitro peak drug concentration from 2 to 10 times the plateau (or drug solubility) over the short supersaturation period. These results are not surprising since the peak duration and extent of supersaturation are very low in each of these two scenarios. In contrast, when the in vitro peak drug concentration is high (e.g., 10 times the plateau concentration), increasing the peak duration, T g m, from 10 to 60 min increases the amount of drug absorbed by 150% of the original value. Furthermore, when the peak duration is longer (e.g., T g m = 60 min)Footnote 9, the bioavailability enhancement is increased by about 250% when the peak concentration is raised 5 times (i.e., C g m/C g p from 2 to 10).

Figure 7a, d, g details the amount of drug absorbed in each absorption phase for each case illustrated in Fig. 5. When phases i and ii dominate (i.e., when the duration of the peak is long, e.g., T g m = 60 min), the increase in the amount of drug absorbed is more closely proportional to in vitro peak drug concentration. However, when phase iii dominates, as is the case when the duration of the peak is short (e.g., T g m = 10 min), reformulation strategies taken to increase C g m/C g p will result in a less than proportional increase in drug absorption that may not be worth the development effort.

Amount of drug absorbed in each phase of the in vivo drug concentration (in the small intestinal lumen) vs. time profile. Case 1 (a–c), Case 2 (d–f), and Case 3(g–i), at different k a values (0.001, 0.01, 0.1 min−1) for a range of T g m (10–60 min) and C g m/C g p (2–10). Blue bars represent the amount of drug absorbed during phase i, red bars represent the amount absorbed during phase ii, and green bars represent the amount absorbed during phase iii

Drugs with an Intermediate Absorption Rate Constant (k a = 0.01 min−1)

Next, we consider drugs which have the same in vitro dissolution profiles as explored above, but now which have an order of magnitude greater absorption rate constant. Figure 6b, e, h shows about an order of magnitude increase in the amount of drug absorbed over Fig. 6a, d, and g, respectively. In fact, for Case 1, where the assumption is that the in vivo drug concentration-time profile mirrors exactly that observed in vitro, increasing k a by one order of magnitude will increase drug absorption by exactly one order of magnitude (Fig. 6a–c and Eq. 8). In contrast, when the drug concentration-time profile in vivo does not exactly mirror that in vitro, but rather differs in the manner described by either Case 2 or 3, the amount of drug absorbed is not proportional to k a.

In Case 2, where the in vivo peak is dependent-on-time and corresponds to in vitro time to peak, the amount absorbed is less than proportional to the absorption rate constant, whereas using the Case 3 assumptions, the amount of drug absorbed is more than proportional to k a. This contrast is most clearly seen when the peak concentration and peak duration are both large (Fig. 6d vs. e and g vs. h). In this example, two drugs with the same in vitro dissolution profiles are characterized by T g m = 60 min and C g m/C g p = 10. The drug with a k a of 0.01 min−1 (vs. 0.001 min−1) results in a 700% higher amount of drug absorbed using Case 2 assumptions (Fig. 6d vs. e).Footnote 10 In contrast, using Case 3 assumptions, the extent of drug absorption is 1200% greater (Fig. 6g vs. h). In comparison, for Case 1, the increase in absorption is exactly one order magnitude greater or 900% (Fig. 6a vs. b). Therefore, the increase in the amount of drug absorbed one would expect for drugs with larger absorption rate constants (assuming the same in vitro dissolution profile) is highly dependent on the relationship between the in vitro and in vivo dissolution profiles (i.e., Case 2 vs. Case 3 assumptions). Until we can reliably extrapolate in vitro dissolution to in vivo, it is useful to quantitatively explore the effect of these two extremes in behavior on the potential range of amount of drug absorbed.

Assuming that the peak duration in vivo corresponds to the peak duration of in vitro (dependent-on-time precipitation—Case 2), the duration of phase ii (Fig. 5b) is greatly reduced due to the depletion of drug by absorption, with much of drug absorption taking place from the lower concentration in phase iii (Fig. 7e). The time to reach plateau concentration, T l p 2, is dramatically reduced as k a increases (Fig. 8a). This shorter time to the plateau concentration is also due to the lower in vivo peak drug concentration (C l m 2) at higher values of k a (Fig. 8b). Values of C l m 2 can be lower than C g p. This occurs when the maximum supersaturation ratio (C g m/C g p) is less than the product of k a and T g m resulting in no phase ii.

Using Case 2 assumptions, a the time to reach plateau drug concentration in vivo (T l p 2) and b the maximum drug concentration in vivo (C l p 2) at different values of k a (0.001, 0.01, 0.1 min−1) for a range of T g m (10–60 min) with C g m/C g p held constant at 6. Using Case 3 assumptions, c the time to reach maximum drug concentration (T l m 3). Asterisk indicates values approaching infinity

In contrast, we can explore the alternative assumption that the peak drug concentrations in vivo and in vitro reach equal values (dependent-on-concentration precipitation—Case 3). In this case, drug depletion by absorption lengthens the time to reach in vivo peak concentration. Therefore, as the in vitro peak duration increases (i.e., higher T g m), phase i dominates (Fig. 7g vs. h) since time to maximum concentration (T l m 3) increases and eventually exceeds the intestinal transit time (T l r) (Fig. 8c) (Eq. 12b).

Drugs with Large Absorption Rate Constant (k a = 0.1 min−1)

Case 1 assumptions do not account for depletion of dissolved drug due to absorption. So, the trends in the amount of drug absorbed (Fig. 6c) are similar to those seen for the low (Fig. 6a) and intermediate (Fig. 6b) absorption rate constants, only an order of magnitude higher than for k a = 0.01 min−1. However, an absorption half-life corresponding to k a of 0.1 min−1 is less than 10 min, which is short compared to the small intestinal transit time. Therefore, Case 1 is much less appropriate to use for high absorption rate constant drugs, due to depletion through absorption.

Using Case 2 and Case 3 assumptions, where the in vivo drug concentration profiles do not mirror those in vitro, the effect of enhancing the in vitro drug concentration profile has more interesting consequences on drug absorption. For the case in which the duration of the in vitro peak drug concentration corresponds to in vivo, Case 2, the amount of drug absorbed is fairly insensitive to alterations in the in vitro dissolution profile as characterized by T g m and C g m (Fig. 6f vs. d). This result can be traced to the reduction in the time to plateau, T l p 2, by depletion due to absorption (Fig. 8a, b and Eq. 9b); little to no drug is absorbed in phase ii at the highest value of k a (Fig. 7f vs. d). For drugs with very high absorption rate constants, formulation efforts to increase the duration of the peak would actually lead to a slight decrease in drug absorption, assuming dependent-on-time precipitation, Case 2.

The opposite is true for Case 3, which assumes the in vivo peak drug concentration reaches the in vitro value. Drugs with very high k a (0.1 min−1) have in vivo peak durations, T l m 3, that exceed the small intestinal transit time (180 min) (Fig. 8c). Consequently, when absorption half-life approaches T g m, T l m 3 approaches infinity and phase i completely dominates (Fig. 7i) the absorption profile. Therefore, the total amount of drug absorbed can be found from Eq. 12b. As in the case of drugs with intermediate absorption rate constants (k a = 0.01 min−1), we also find some counterintuitive consequences of altering the in vitro drug concentration profile for drugs with very high absorption rate constants (k a = 0.1 min−1). According to Eq. 12b, drug absorbed is proportional to C g m/T g m. Thus, a decrease in peak duration results in greater amount of drug absorbed. This counterintuitive result can be explained by examining the phases of absorption in more detail. For a given dissolution enhancement, C g m/C g p, a shorter peak duration in vitro translates to a shorter time to peak (using the isosceles triangular approximation) which provides more drug in solution sooner. When the absorption rate constant is very high, a large amount of drug is absorbed, maintaining the in vivo drug concentration below in vitro peak concentration that presumably “triggers” precipitation, in this case. The consequence is that the in vivo drug concentration remains supersaturated for the duration of the intestinal transit time.

Sensitivity of the Absorption Estimate to Geometry of Peak

The above results are based on the three-parameter isosceles triangular approximation of the in vitro drug concentration peak. To assess any bias imposed by this approximation, an alternative equivalent rectangular peak shape was explored. The rectangular peak was considered to represent the opposite extreme to the single time point at C g m in the triangular approximation. Using a rectangular shape to approximate the peak, maximum drug concentration ranges from t = 0 to the end of phase ii (Supplemental 2). A comparison of triangular and rectangular peak approximations was performed for Case 2 since Case 2 generally includes all three phases unlike Case 3 which remains in phase i when the product of k a and T g m is large.

The amount of drug absorbed calculated from the triangular peak approximation differed from either rectangular approximations by −10 to 30% (Supplemental 4). The bias introduced by using the triangular peak approximation is small compared to the effect of maximum peak concentration, peak duration, and absorption rate constant shown in the previous section (Fig. 7). This analysis provides the confidence to use the three-parameter isosceles triangular approximation to quantitatively explore drug absorption for supersaturating drug delivery systems using Eqs. 8, 9a, 9b, 12a, or 12b, depending on the assumptions one wishes to make regarding the relationship of in vivo dissolution and in vitro dissolution behavior. More details can be found in Supplemental 3.

DISCUSSION

Reports show that measures of enhanced dissolution are not always predictive of enhanced bioavailability (5,25). Potential reasons for the discrepancies were explored quantitatively using absorption models that require limited data. The closed-form equations developed here can also be used to determine the potential effects of key dissolution and physiological parameters on bioavailability for a promising new chemical entity with limited solubility.

The in vitro peak drug concentration and peak duration produced by supersaturating dosage forms are highly dependent on the drug, drug form, formulation components, and solution composition (5,28–33,38,39,48–50). To bracket a range of bioavailability that could be reasonably expected from supersaturating dosage forms, two alternative assumptions were used: either (a) the duration of the peak drug concentration in vivo corresponds to the in vitro data or b) the drug concentration in vivo reaches the peak concentration observed during in vitro dissolution. When we assumed that the duration of the in vivo peak corresponds to the in vitro peak duration (i.e., Case 2), drug absorption was predicted to be less sensitive to alterations in the in vitro dissolution profile, especially for drugs with moderate to high k a values (0.01–0.1 min−1). It is particularly notable that when the absorption rate constant is high (k a = 0.1 min−1), formulation efforts to increase the in vitro drug concentration peak or duration are predicted to lead to a slight decrease in the amount of drug absorbed using Case 2 assumptions (Fig. 6f).

Contrast this result with Case 3, where the in vivo peak drug concentration is assumed to reach the in vitro peak value, despite depletion due to drug absorption. In this case, the amount of drug absorbed was very sensitive to alterations in the in vitro dissolution profile, particularly for compounds with high k a values. When k a is very large (k a = 0.1 min−1), formulation efforts to increase the drug peak concentration and/or decrease the peak duration were predicted to result in a substantial increase in drug absorption using Case 3 assumptions (Fig. 6i). In general, when the absorption rate constant of a drug is known or can be estimated, the current models may be useful to quantitatively explore whether or not it would be worth the effort to formulate for enhanced in vitro dissolution profiles.

In contrast to Cases 2 and 3, Case 1 predicts that the amount of drug absorbed is influenced by absorption rate constant, the peak concentration, and its duration in a straightforward manner. However, Case 1 only applies to a limited number of drugs which have both low solubility and very low absorption rate constants, such as BCS IV compounds. Case 1 is of limited use since most supersaturating drug delivery systems in development are formulated for BCS II compounds which have low solubility but higher absorption rate constant.

Several approaches to characterizing in vitro concentration vs. time curves were considered, including the simplest approach, the AUC approach. However, the AUC approach could not be utilized for Cases 2 and 3 without underestimating the amount of drug absorbed due to significant drug depletion. Therefore, an approximation or some estimate of a function that describes the course of the dissolved drug concentration was required. The isosceles triangulation approach was selected over others because it was a good representation of various experimental in vitro concentrations vs. time curve. Furthermore, this approach allowed the math to be significantly simplified, yielding closed analytical solutions.

For each of these cases, the in vitro concentration-time curves are quickly characterize by the isosceles triangular approximation using just the three parameters: (1) peak drug concentration, (2) duration of the peak which is characterized by the full width at half maximum, and (3) the plateau drug concentration that often follows the peak. A comparison of the three-parameter triangular approximation with an equivalent rectangular peak showed that peak shape had much less influence on estimates of drug absorption than parameters such as absorption rate constant, in vitro peak drug concentration, and its duration. In short, for the purposes of rapidly calculating the potential effects of reformulation on bioavailability, the use of only three parameters to characterize the in vitro dissolution triangle profile provides a reasonable estimate of drug absorption without incurring large bias. Furthermore, this approach permits derivation of closed analytical solutions.

This analysis assumes the in vitro dissolution medium is carefully selected to mimic in vivo conditions, since three out of the six parameters needed for the model are determined from the in vitro drug concentration-time profiles. Important factors to consider when performing dissolution experiments are temperature, hydrodynamics, and medium selection (28–33). For example, the addition of bile salts and/or phospholipids has been shown to alter drug precipitation kinetics (33) by effecting the nucleation and/or crystal growth rate (28,51).

Two physiological parameters used in this model are small intestinal fluid volume, V l, and small intestinal transit time, T l r. An increase in V l results in a proportional increase in the estimated drug absorbed (Eqs. 8, 9a, 9b, 12a, and 12b) in all cases. However, time dependence of the small intestinal fluid volume containing the drug will likely have more complex effects. Furthermore, variation in small intestinal transit time also leads to variation in the amount of drug absorbed, at least for cases in which there is undissolved drug remaining at the end of the absorption process as assumed in this work. Additional assumptions that limit the applicability of Eqs. 8, 9a, 9b, 12a, and 12b are described in the “MODEL DEVELOPMENT” section. Models may also be evaluated for nonenteric drug forms due to the slow introduction into the small intestine.

The advantage of the current approach is the small number of input parameters required to define key aspects affecting bioavailability. Due to the limited number of input variables, the models can be used to quantify variation in bioavailability based on known variations of small intestinal fluid volume and small intestinal transit time, as well as potential or experimentally determined variation in drug peak concentration and duration. Future studies will focus on using this model to evaluate variations in bioavailability contributed from both physiological and formulation input parameters which may potentially lead to clinically unacceptable high variation in the performance of the drug product.

CONCLUSION

Two alternative assumptions (i.e., equal drug peak concentrations or corresponding peak durations in vitro and in vivo) lead to what are expected to be two extremes in effect of reformulation on bioavailability of precipitating dosage forms. If we assume equivalent peak duration in vitro and in vivo, the model suggests that formulation improvements will have less impact on bioavailability than if we assume equal peak concentrations are reached. A simpler case, wherein both the peak drug concentration and peak duration are both assumed equal in vitro and in vivo, leads to a bioavailability estimate that lies between the extremes. The simpler case provides a more straightforward calculation, but its applicability may be limited to drugs with low absorption rate constant.

Until we can reliably extrapolate in vitro dissolution to in vivo, it is useful to quantitatively explore the effect of these two extremes in behavior on the potential range of amount of drug absorbed. The models developed here may be a useful tool to guide the thinking of formulators; potential outcomes of proposed strategies to either increase the peak drug concentration and/or the peak duration can be quantitatively evaluated using Eqs. 8, 9a, 9b, 12a, or 12b depending on assumptions.

Notes

The subscript g denotes in vitro (Latin for “in glass”). See Table I for a full description of the nomenclature.

Furthermore, it retains the benefits of using an isosceles triangle to approximate the peak. For example, the width of the base of the isosceles triangle which lies at C g p is exactly twice T HM as shown in Fig. 3. Additionally, the width of the base of the larger isosceles triangle is twice T g m, the time to reach the apex of the isosceles triangle.

The subscript l denotes in vivo (Latin for “within the living”). See Table I for a full description of the nomenclature.

Drug precipitates to what is thought to be very small particles, perhaps in the nanometer range. These many minute drug particles have a very large surface area, making it less likely that dissolution is rate limiting.

Neglect for the purpose of this simple case, the reduction in drug concentration in the lumen due to absorption. This is handled in Case 2 and Case 3.

\( {\left.{X}_{\mathrm{l}}{a}_1\right|}_0^{T_{\mathrm{l}}r} \) is also equal to the product of k a and AUC of the in vivo concentration vs. time profile since the assumption is made that in vivo drug concentration vs. time curve mirrors the in vitro.

The subscript g denotes in vitro (Latin for “in glass”) and the subscript l denotes in vivo (Latin for “within the living”). A second subscript indicates the case (see Table II).

Percent change is expressed as a percent of the difference between new value and the original value relative to the original value. For example, if absorption increases from 5 to 10 mg, the percent increase is 100%.

T g m is equal to the width of the peak at half maximum and not equal to the actual peak width at itsbase, which is about 2 times T g m.

Nota bene the z-axis (total amount of drug absorbed) is different for each k a value. For k a = 0.01 min−1 (panels a, d, g), y = 0 to 0.6 mg; for k a = 0.01 min−1 (panels b, e, h), y = 0 to 6 mg; and for k a = 0.1 min−1 (panels c, f, i), y = 0 to 120 mg.

References

Amidon GL, Lennernas H, Shah VP, Crison JR. A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification: the correlation of in vitro drug product dissolution and in vivo bioavailability. Pharm Res. 1995;12(3):413–20.

van Hoogevest P, Liu X, Fahr A. Drug delivery strategies for poorly water-soluble drugs: the industrial perspective. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8(11):1481–500.

Murdande SB, Pikal MJ, Shanker RM, Bogner RH. Solubility advantage of amorphous pharmaceuticals, part 3: is maximum solubility advantage experimentally attainable and sustainable? J Pharm Sci. 2011;100(10):4349–56.

Brouwers J, Brewster ME, Augustijns P. Supersaturating drug delivery systems: the answers to solubility-limited bioavailability? J Pharm Sci. 2008;98(8):2549–72.

Greco K, Bogner R. Solution-mediated phase transformation: significance during dissolution and implications for bioavailability. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101(9):2996–3018.

Crison JR, Amidon GL. The effect of particle size distribution on drug dissoltion: a mathematical model for predicting dissolution and absorption of suspensions in the small intestine. Pharm Res. 1992;10:S170.

Dokoumetzidis A, Kalantzi L, Fotaki N. Predictive models for oral drug absorption: from in silico methods to integrated dynamical models. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2007;3(4):491–505.

Dressman JB, Amidon GL, Fleisher D. Absorption potential: estimating the fraction absorbed for orally administered compounds. J Pharm Sci. 1985;74(5):588–9.

Dressman JB, Fleisher D. Mixing-tank model for predicting dissolution rate control of oral absorption. J Pharm Sci. 1986;75(2):109–16.

Dressman JB, Fleisher D, Amidon GL. Physiochemical model for dose-dependent drug absorption. J Pharm Sci. 1984;73(9):1274–9.

Goodacre BC, Murry RJ. A mathematical model of drug absorption. J Clin Hosp Pharm. 1981;6:117–33.

Macheras P, Symillides MY. Toward a quantitative approach for the prediction of the fraction of dose absorbed using the absorption potential concept. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1989;10:43–53.

Oh D-M, Curl RL, Amidon GL. Estimating the fraction dose absorbed from suspensions of poorly soluble compounds in humans: a mathematical model. Pharm Res. 1993;10:264–70.

Sinko PJ, Leesman GD, Amidon GL. Predicting fraction dose absorbed in humans using a macroscopic mass balance approach. Pharm Res. 1991;8(8):979–88.

Yu LX, Crison JR, Amidon GL. A strategic approach for predicting oral drug absorption. Pharm Res. 1995;12:S8.

Rinaki E, Dokoumetzidis A, Valsami G, Macheras P. Identification of biowaivers among class II drugs: theoretical justification and practical examples. Pharm Res. 2004;21(9):1567–72.

Yu LX, Lipka E, Crison JR, Amidon GL. Transport approaches to the biopharmaceutical design of oral drug delivery systems: prediction of intestinal absorption. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1996;19:359–76.

Johnson KC, Swindell AC. Guidance in the setting of drug particle size specification to minimize variability in absorption. Pharm Res. 1996;13:1795–8.

Curatolo W. Physical chemical properties of oral drug candidates in the discovery and exploratory development settings. Pharm Sci Technol Today. 1998;1(9):387–93.

Dressman JB, Thelen K, Willmann S. An unpdate on computational oral absorption simulation. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7(11):1345–64.

Jamei M, Turner D, Yang J, Neuhoff S, Polak S, Rostami-Hodjegan A, et al. Population-based mechanistic prediction of oral drug absorption. AAPS J. 2009;11(2):225–37.

Sutton SC. Role of physiological intestinal water in oral absorption. AAPS J. 2009;11(2):277–85.

Johnson KC. Dissolution and absorption modeling: model expansion to simulate the effects of precipitation, water absorption, longitudinally changing intestinal permeability, and controlled release on drug absorption. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2003;29(8):833–42.

Chiang PC, La H, Zhang H, Wong H. Systemic concentrations can limit the oral absorption of poorly soluble drugs: an investigation of non-sink permeation using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. Mol Pharm. 2013;10(11):3980–8.

Kaushal AM, Gupta P, Bansal AK. Amorphous drug delivery systems: molecular aspects, design, and performance. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2004;21(3):133–93.

Abbou Oucherif K, Raina S, Taylor LS, Litster JD. Quantitative analysis of the inhibitory effect of HPMC on felodipine crystallization kinetics using population balance modeling. Cryst Eng Commun. 2013;15(12):2197–205.

Dokoumetzidis A, Macheras P. A population growth model of dissolution. Pharm Res. 1997;14(9):1122–6.

Alonzo DE, Zhang GG, Zhou D, Gao Y, Taylor LS. Understanding the behavior of amorphous pharmaceutical systems during dissolution. Pharm Res. 2010;27(4):608–18.

Bevernage J, Brouwers J, Brewster ME, Augustijns P. Evaluation of gastrointestinal drug supersaturation and precipitation: strategies and issues. Int J Pharm. 2013;453(1):25–35.

Chen LR, Wesley JA, Bhattachar S, Ruiz B, Bahash K, Babu SR. Dissolution behavior of a poorly water soluble compound in the presence of Tween 80. Pharm Res. 2003;20(5):797–801.

Dressman JB, Amidon GL, Reppas C, Shah VP. Dissolution testing as a prognostic tool for oral drug absorption: immediate release dosage forms. Pharm Res. 1998;15(1):11–22.

Dressman JB, Reppas C. In vitro-in vivo correlations for lipophilic, poorly water-soluble drugs. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000;11 Suppl 2:S73–80.

Rodriguez-Hornedo N, Murphy D. Surfactant-facilitated crystallization of dihydrate carbamazepine during dissolution of anhydrous polymorph. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93(2):449–60.

Murdande SB, Pikal MJ, Shanker RM, Bogner RH. Solubility advantage of amorphous pharmaceuticals: II. Application of quantitative thermodynamic relationships for prediction of solubility enhancement in structurally diverse insoluble pharmaceuticals. Pharm Res. 2010;27(12):2704–14.

McConnell EL, Fadda HM, Basit AW. Gut instincts: explorations in intestinal physiology and drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2008;364(2):213–26.

Polli JE, Crison JR, Amidon GL. New approach to the analysis of in vitro-in vivo relationships. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85(7):753–60.

Schiller C, Frohlich CP, Giessmann T, Siegmund W, Monnikess H, Hosten N, et al. Intestinal fluid volumes and transit of dosage forms as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:971–9.

Brouwers J, Brewster ME, Augustijns P. Supersaturating drug delivery systems: the answer to solubility-limited oral bioavailability? J Pharm Sci. 2009;98(8):2549–72.

Greco K, Bogner R. Crystallization of amorphous indomethacin during dissolution: effect of processing and annealing. Mol Pharm. 2010;7(5):1406–18.

Ilevbare GA, Taylor LS. Liquid-liquid phase separation in highly supersaturated aqueous solutions of poorly water-soluble drugs: implications for solubility enhancing formulations. Cryst Growth Des. 2013;13(4):1497–509.

Bevernage J, Brouwers J, Annaert P, Augustijns P. Drug precipitation-permeation interplay: supersaturation in an absorptive environment. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;82(2):424–8.

Chauhan H, Hui-Gu C, Atef E. Correlating the behavior of polymers in solution as precipitation inhibitor to its amorphous stabilization ability in solid dispersions. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102(6):1924–35.

Charkoftaki G, Dokoumetzidis A, Valsami G, Macheras P. Elucidating the role of dose in the biopharmaceutics classification of drugs: the concepts of critical dose, effective in vivo solubility, and dose-dependent BCS. Pharm Res. 2012;29(11):3188–98.

Marciani L, Cox EF, Hoad CL, Pritchard S, Totman JJ, Foley S, et al. Postprandial changes in small bowel water content in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):469–77. 77 e1.

Yu LX, Crison JR, Amidon GL. Compartmental transit and dispersion model analysis of small intestinal transit flow in humans. Int J Pharm. 1996;140(1):111–8.

Fadda HM, McConnell EL, Short MD, Basit AW. Meal-induced acceleration of tablet transit through the human small intestine. Pharm Res. 2009;26(2):356–60.

Lennernas H. Intestinal permeability and its relevance for absorption and elimination. Xenobiotica. 2007;37(10–11):1015–51.

Fagerberg JH, Tsinman O, Sun N, Tsinman K, Avdeef A, Bergstrom CA. Dissolution rate and apparent solubility of poorly soluble drugs in biorelevant dissolution media. Mol Pharm. 2010;7(5):1419–30.

Jantratid E, Janssen N, Reppas C, Dressman JB. Dissolution media simulating conditions in the proximal human gastrointestinal tract: an update. Pharm Res. 2008;25(7):1663–76.

Greco K, Bogner R. Solution-mediated phase transformation of haloperidol mesylate in the presence of sodium lauryl sulfate. AAPS Pharm Sci Technol. 2011;12(3):909–16.

Kleppe MS. Comparison of biorelevant media and USP compendial media on solution-mediated transformation of amorphous drug during dissolution. AAPS Northeast Regional Discussion Group Meeting; 2013 Apr 19; Rocy Hill, CT.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jeff Browne, Kevin Johnson, and Jonathan Miller for their helpful discussions. M. Kleppe was supported in part by the Dane O. Kildsig Center for Pharmaceutical Processing Research (CPPR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplemental 1

(DOCX 55 kb)

Supplemental 2

(PPTX 104 kb)

Supplemental 3

(DOCX 36 kb)

Supplemental 4

(PPTX 196 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kleppe, M.S., Forney-Stevens, K.M., Haskell, R.J. et al. Mathematical Models to Explore Potential Effects of Supersaturation and Precipitation on Oral Bioavailability of Poorly Soluble Drugs. AAPS J 17, 902–917 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-015-9748-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-015-9748-2