Abstract

Nasal administration of influenza vaccine has the potential to facilitate influenza control and prevention. However, when administered intranasally (i.n.), commercially available inactivated vaccines only generate systemic and mucosal immune responses if strong adjuvants are used, which are often associated with safety problems. We describe the successful use of a safe adjuvant Gram-positive enhancer matrix (GEM) particles derived from the food-grade bacterium Lactococcus lactis for i.n. vaccination with subunit influenza vaccine in mice. It is shown that simple admixing of the vaccine with the GEM particles results in a strongly enhanced immune response. Already after one booster, the i.n. delivered GEM subunit vaccine resulted in hemagglutination inhibition titers in serum at a level equal to the conventional intramuscular (i.m.) route. Moreover, i.n. immunization with GEM subunit vaccine elicited superior mucosal and Th1 skewed immune responses compared to those induced by i.m. and i.n. administered subunit vaccine alone. In conclusion, GEM particles act as a potent adjuvant for i.n. influenza immunization.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Seasonal influenza is still one of the major causes for mortality and morbidity worldwide (1). Annual vaccinations are the most effective strategy to prevent and control influenza infections (2,3). Most of the available influenza vaccines are administered via the intramuscular (i.m.) or subcutaneous route. These parenteral vaccines induce good systemic immune response but no mucosal immune response (3–5), which limits their protective efficacy. In contrast, intranasal (i.n.) vaccines may induce both systemic and mucosal immune responses (6–9). In addition, i.n. delivery of the vaccine does not require trained health care personnel for the administration of vaccine, is suitable for people with needle phobia, and circumvents the problem of needlestick injuries (10).

A mucosal immune response is necessary for the protection of the upper respiratory tract, i.e., the port of entry for influenza virus (6,11). The protection of the upper respiratory tract is mainly provided by sIgA (3,6,12). Moreover, sIgA is known to induce cross-protection against variant viruses within the same subtype and also increase the protection during epidemics of heterologous viruses (6,13–18). Furthermore, it is reported that the mucosal immune system develops early in life and is not affected by aging (19,20). Therefore, a concomitant advantage of i.n. influenza immunization is that it can potentially provide effective immunity in all age groups and can be used for mass vaccination.

Currently, live attenuated influenza virus vaccines (LAIV) are marketed for i.n. administration. LAIV vaccines have shown to induce both systemic and mucosal immune responses. However, LAIV vaccine is licensed by the Food and Drug Administration only for persons aged 2–49 years but not for use in high-risk populations (elderly, children, and chronically ill patients) (21,22). However, most of the marketed influenza vaccines are inactivated vaccines which can be administered safely via i.n. route to the whole population. A disadvantage of these vaccines is that they have shown to be poorly immunogenic when administered via this route (4,13).

To increase the immunogenicity, inactivated influenza vaccines require adjuvants to potentiate the immune response when administered via the i.n. route. Several adjuvants are currently under development for i.n. immunizations like virus-like particles (23), immunostimulating complexes (ISCOMS) (23), lipids, nucleic acids (24), and bacterial components (25,26). However, the development of many of these adjuvants systems is hampered by safety and regulatory concerns (27). For example, potent bacterial adjuvants like heat liable toxin of Escherichia coli (LT) have shown severe side effects in humans (28). Therefore, an adjuvant for i.n. inactivated influenza vaccine that is potent and safe for human use is still lacking.

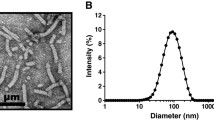

The novel adjuvant Gram-positive enhancer matrix (GEM) particles are produced from the food-grade bacterium Lactococcus lactis (29). L. lactis is a nonpathogenic, noncolonizing Gram-positive bacterium. Moreover, L. lactis is approved for human use by regulatory agencies and considered as a generally recognized as safe (GRAS) organism. The GEM particles are produced by heating the L. lactis in acid, followed by washing with phosphate buffer (30). The resulting particles are nonliving, deprived of intact surface proteins and intracellular content. The thick peptidoglycan cell wall, however, remains intact and provides the structural rigidity to constitute the bacterial-shaped peptidoglycan spheres of about 1 μm in size, referred to as GEM particles. The GEM particles have been studied for mucosal vaccination of malarial parasite antigen and pneumococcal antigens (31–33). These studies demonstrated that antigens displayed on GEM particles induced higher immune response than antigen alone. Since GEM particles are a promising adjuvant for i.n. immunization, the aim of this study was to investigate the use of GEM particles as adjuvant for i.n. influenza vaccination.

In this study, we examined the immunogenicity in Balb/c mice of i.n. administered influenza subunit vaccine mixed with GEM particles as adjuvant. In earlier studies, the antigens (pneumococcal and malarial) were covalently bound to the GEM particles (29–33). In contrast, in the present study, the particles were simply mixed with the antigens. The immune response was compared to i.m. and i.n. administered subunit influenza vaccine without the adjuvant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Influenza monovalent subunit vaccine of strain A/Wisconsin (H3N2) was kindly provided by Solvay Pharmaceuticals (Weesp, The Netherlands). The concentration of the hemagglutinin (HA) in the vaccine was determined using the single radial immunodiffusion assay.

Gem Preparation

GEM particles were prepared as described earlier (29). In brief, cells of an overnight culture of L. lactis strain MG1363acmAΔ1 were harvested and washed once with sterile distilled water. The cells were resuspended in 10% trichloroacetic acid and placed in a hot water bath of 99°C for 30 min. The acid and heat treatment kills the bacteria and generates the so-called GEM particles. After acid and heat treatment, the GEM particles were pelleted and washed three times in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline without CaCl2 and MgCl2) and finally resuspended in PBS and stored at −20°C. One unit of GEM particles was defined as approximately 2.5 × 109 nonliving particles.

Immunization

Animal experiments were evaluated and approved by the Committee for Animal Experimentation of the University of Groningen, The Netherlands according to the guidelines provided by Dutch Animal Protection Act. Balb/c mice (6–8 weeks) purchased from Harlan, Zeist, The Netherlands were used for all immunization experiments. The mice were divided in three groups of eight each. All three groups of animals were immunized with prime vaccination on day 0 and two booster vaccinations on days 14 and 28 with 5 μg of HA. The influenza subunit vaccine and the GEM particles were admixed just before the immunization. The test group was immunized intranasally with 12 µl of GEM adjuvanted vaccine (2.5 × 109 GEM particles (1 U) were mixed with 12 µl of 5 µg HA) divided over both the nostrils under inhalation anesthesia (isoflurane/O2). In two control groups, one group was injected with an intramuscular injection of 50 μl vaccine in posterior thigh muscles under inhalation anaesthesia (isoflurane/O2) and second group was administered 12 µl of vaccine intranasally under inhalation anaesthesia (isoflurane/O2). The mice were sacrificed 2 weeks after the second booster vaccination, i.e., on day 42. After the animals were sacrificed, the spleens of the animals were harvested and subsequently stored in supplemented Iscoves’s modified Dulbecco’s medium–glutamax medium with 5% fetal calf serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol at 4°C.

Sera Collection and Mucosal Washes

Blood samples were drawn three times during the experiments, i.e., on day 0 and 28 by orbital puncture and day 42 by heart puncture. Sera were obtained by centrifugation of blood at 1,200×g for 5 min, and the samples were subsequently stored at −20°C until further analysis.

Nasal and lung lavages were performed as described earlier (34). Briefly, the trachea of each mouse was cannulated and connected to a 1-ml syringe. Lung washes were taken by repeated flushing of lungs with 1 ml PBS (pH 7). Nasal washes were obtained by flushing the nasopharynx with 1 ml PBS. Subsequently, the mucosal washes were admixed with 10 µl of protease inhibitor solution (one tablet Complete® protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche diagnostics) dissolved in 2 ml PBS).

ELISA

The antibody response to the influenza subunit antigen was determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays as described previously (34). Briefly, the plates were incubated with 200 ng of HA/well. After overnight incubation with HA, the plates were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, The Netherlands). Then, plates were washed and incubated with sera and mucosal samples in serial dilution for 1.5 h at 37°C. Next, the plates were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antibodies directed against mouse IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgA (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). Finally, the substrate solution (0.02% 1,2-phenyllendiamine dihydrochloride in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 5.6, containing 0.006% H2O2) was added and the plates were incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by addition of 2 M H2SO4, and absorbance at 490 nm was read with a Benchmark Microplate reader (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Titers reported are the reciprocal of the calculated sample dilution corresponding with an A490 ≥ 0.2 after background correction.

Hemagglutination Inhibition Assay

Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers in serum were determined as described previously (34). Briefly, serum was inactivated at 56°C for 30 min. In order to reduce nonspecific hemagglutination, 25% kaolin suspension was added to inactivated sera. After centrifugation at 1,200×g, 50 µl of the supernatant was transferred in duplicate to 96-well round-bottom plate (Greiner, Alphen a/d Rijn, The Netherlands) and serially diluted twofold in PBS. Then, four hemagglutination units of A/Wisconsin influenza inactivated virus were added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 40 min at room temperature. Finally, 50 µl of 1% guinea pig red blood cells was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The highest dilution capable of preventing hemagglutination was scored as HI titer.

ELISPOT

The Elispot assay was performed as described earlier (35). Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (Greiner, Alphen a/d Rijn, The Netherlands) were incubated overnight at 4°C with antimouse interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4; BD, Pharmingen, Erembodegem, Belgium). After washing the plates three times with PBS/Tween (Sigma-Aldrich, The Netherlands), they were blocked (PBS + 4% BSA) for 1 h at 37°C, and spleen cells were added to the plates in concentration 1 × 106 cells/well with or without subunit vaccine as a stimulation peptide. After incubation overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2, the cells were lysed with cold water. Next, the plates were washed five times with PBS/Tween and incubated with biotinylated antimouse IFN-γ and IL-4 antibodies (BD Pharmingen) in concentration of 0.125 µg/ml in PBS + 2% BSA. After washing, the plates were incubated with streptavidin alkaline phosphatase (BD Pharmingen) for 1 h at 37°C. Finally, after washing three times with PBS/Tween and two times with PBS, the spots were developed using the substrate solution consisting of 1 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate, 0.92% (w/v) 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol, 0.08 µl/ml TritonX-405, 1 M MgCl2, and 6 mg/ml agarose. The spots were counted using an Elispot reader (A.EL.VIS Elispot reader).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test with p < 0.05 as the minimal level of significance. The results are presented as mean ± standard error mean unless indicated otherwise.

RESULTS

Systemic Immune Response

The protective capacity of influenza vaccines was determined by measuring HI titers. The HI titers were determined for all mice after the first and second booster immunization. Figure 1 shows that both the conventional i.m. and the GEM adjuvanted i.n. vaccines reached comparable HI titers above 2log6 after the first booster immunization (p = 0.2062). These titers increase in both cases to values between 2log7 and 2log8 with no significant differences (p = 0.7611). I.n. immunization with the subunit vaccine alone induced low HI titers, even after two booster immunizations. Moreover, only 50% of the animals responded after immunization with i.n. subunit vaccine, while all animals responded in the two other vaccine groups. Since an HI titer above 2log5 is considered to be protective in humans, these results indicate that one single boost is sufficient for i.n. GEM adjuvanted influenza vaccines to reach protective immunity.

Subunit antigen-specific HI titers in mice immunized three times. a Comparative analysis of HI titers in different groups, i.e., i.m., i.n., and i.n. + GEM at 0, 28, and 42 days after the first immunization. b Comparative analysis of HI titers between three groups, i.e., i.m., i.n., and i.n. + GEM at 42 days after first immunization. The numbers above the columns indicate the number of responders per group

As expected, i.m. immunization with conventional subunit vaccine resulted in robust IgG responses while this vaccine without adjuvant was poorly immunogenic when administered via the i.n. route (26,36–38). Figure 2 shows the subunit antigen-specific IgG response after two booster doses. Even after two booster doses, i.n. immunization with subunit vaccine alone induced lower (p < 0.01) IgG responses than i.n administered HA + GEM, clearly demonstrating the adjuvant effect of the GEM particles. While the i.m. immunization with conventional subunit vaccine resulted in a higher response (p = 0.0101) than i.n. immunization with HA + GEM after the first booster dose, the IgG response was comparable (p = 0.4355) after the second booster immunization. This is consistent with earlier observations (25,36,39,40) reporting that during i.n. immunization, there is a gradual increase in IgG response.

Subunit antigen-specific total serum IgG titers in mice immunized three times. a Comparative analysis of total serum IgG titers in different groups, i.e., i.m., i.n., and i.n. + GEM at 0, 28, and 42 days after the first immunization. b Comparative analysis of total serum IgG titers between three groups, i.e., i.m., i.n., and i.n. + GEM at 42 days after first immunization. **p < 0.01

Furthermore, i.n. immunization without adjuvant and i.m immunization induced low levels of serum IgA titers (Fig. 3). Moreover, only three out of eight and five out of eight animals responded after i.n. and i.m. immunization with subunit vaccine, respectively. In contrast, i.n. immunization with HA + GEM induced higher (p < 0.05) serum IgA responses than the other two control immunizations, and all animals responded in this group. It is evident from the results that formulation of subunit vaccine with GEM particles induced a strong systemic immune response compared to both i.n. and i.m. immunization with subunit vaccine alone.

Mucosal Immune Response

It has been reported previously that i.n. immunization may induce local mucosal immunity in the respiratory tract, i.e., the port of entry of influenza virus (36,38–40). The activation of the mucosal immunity primes the underlying B and T cells and results in secretion of sIgA at mucosal sites. Consequently, the influenza specific sIgA titers were determined in nasal and lung lavages of the mice (Fig. 4).

I.m. immunizations elicited sIgA levels in nasal and lung lavages below detection limits in most of the mice (only one out of eight mice showed a response in the nasal lavage). Similarly, the i.n. immunizations with subunit vaccine alone gave low sIgA titers in lung and nasal lavages (three out of eight responders). In contrast, i.n. immunization with HA + GEM induced high sIgA titers in nasal and lung lavages of all mice. In conclusion, i.n. immunization with HA + GEM induced a strong mucosal immune response at both the upper and lower respiratory tract.

Phenotype of Immune Response

In order to evaluate the phenotype of the response, i.e., the T-helper 1/T-helper 2 ratio (Th1/Th2), IgG subtypes, and IFN-γ and IL-4 responses were determined. IgG subtype profiling (Fig. 5) showed that i.n. immunization with subunit vaccine alone induced low IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b responses. As previously reported (34,35), i.m. immunization with subunit vaccine induced high IgG1 responses but little IgG2a and IgG2b, indicating an immune response biased toward a Th2-type response. In comparison to i.m. immunization, i.n. immunization with HA + GEM induced significant higher IgG2a (p = 0.042) and IgG2b (p = 0.030) and lower IgG1 (p = 0.0135) responses. These results indicate that the antibody responses generated by i.n. HA + GEM vaccine is significantly more skewed toward a Th1 phenotype than the conventional i.m. vaccine.

The type of immune response (Fig. 6) was further evaluated by determining antigen-specific IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing splenocytes of the immunized mice. I.m. immunization with subunit vaccine resulted in a higher number of IL-4-producing cells than IFN-γ-producing cells, indicating again a predominated Th2-type response. I.n. immunization with subunit vaccine resulted in lower numbers of IL-4-producing cells but substantially higher numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells (Fig. 6), resulting in a balanced Th1/Th2 response. The increase in IFN-γ-producing T cells was even significantly (p = 0.0373) more pronounced after i.n. immunization with HA + GEM, indicating a shift of the immune response from a balanced Th1/Th2 to a predominant Th1-type response. Collectively, these results indicate that the GEM-based i.n. influenza vaccine elicited a response biased toward a Th1 phenotype.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that GEM particles are promising candidates as an adjuvant for the i.n. delivery of the influenza subunit vaccine. Our results show that intranasally administered subunit vaccine adjuvanted with GEM particles (which are simply mixed with vaccine) can be used in a prime-boost vaccination strategy to induce protective levels of HI titers (>2log5 (41)), which is considered to be an important correlate of protection. In addition, the serum IgG results clearly highlight that GEM particles enhance the immunogenicity of the i.n. administered influenza subunit vaccine.

In addition to substantial serum responses, the GEM adjuvanted i.n. vaccine elicited a strong mucosal immune response, i.e., secretion of the sIgA in the respiratory mucosa. These results are consistent with earlier studies (31) in which GEM bound pneumococcal i.n. vaccine induced strong mucosal responses. Induction of significant levels of sIgA in nasal mucosa shows that GEM particles act as immunopotentiators in the nasal mucosa. The immune system of the nasal mucosa consists of the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT). In the NALT, the antigens are taken up by the M-cells and then presented to antigen-presenting cells, which in turn present antigen fragments to the underlying B and T cells (6,13,42,43). This cascade of events is required for the initial innate and adaptive immune response against the influenza virus. The induction of sIgA antibodies in the NALT might be the result of an interaction with Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 of the peptidoglycan present in GEM particles, as it is known that GEM particles act as a TLR-2 agonist in in vitro studies (Pasetti et al., manuscript in communication). Furthermore, it is known that GEM particles can activate the maturation of the dendritic cells and macrophages in vitro (32). Thus, both the activation of TLR-2 and maturation of the dendritic cells might have contributed to the stronger mucosal immune response.

Recently, much emphasis is put on the phenotype of the immune response, i.e., Th1, Th2, or balanced response (44–46). A Th1 response is considered to be superior to Th2 or a mixed response (47) because it (1) results in better protection from infection (16) and (2) helps in virus neutralization by secretion of INF-γ (48). Moreover, the natural infection also induces a Th1 type of response. However, subunit vaccine administered via the i.n. route and many of the nasal adjuvants like chitosan (36,49), ISCOMS (50), lipids (24,51), and LT (25) induce a mixed Th1/Th2-type response. In contrast, the i.n. GEM influenza vaccine induced a response skewed toward Th1 type. Thus, GEM particles modulate the response from a balanced to a Th1-skewed response.

Furthermore, the vaccine formulation presented in this paper is much more convenient to produce compared to most of the other adjuvant systems which have to be preformulated (24,36,39,49–52). The formulation used in these experiments was prepared by ad-mixing the GEM particles with conventional subunit vaccine. GEM particles can be produced in large quantities under sterile conditions and can be stored at ambient temperature for long time (29). The ease of formulation and administration makes i.n. GEM influenza subunit vaccine a promising candidate for vaccination in a pandemic as well as in an epidemic situation.

A major hurdle in the development of mucosal adjuvants is to proof their safety in order to obtain approval by regulatory agencies. The GEM particles used in this study are safe to use in comparison to other adjuvants and other lactic acid bacteria systems evaluated for vaccination (27,53,54). During the production of GEM particles, L. lactis bacteria are treated with acid, which results in loss of genetic material. The loss of the genetic material is beneficial as the problem of DNA shedding and infection in the mucosal layer by the bacteria is avoided (30). Moreover, the GEM particles are produced from a bacterium which is used in the production of dairy products and is considered a GRAS organism. Audouy et al. (31) reported that GEMs did not induce detectable antibody levels to particles themselves after repeated intranasal administrations in mice. In addition, GEM particles have already been tested intranasally in rabbits in a preclinical GLP toxicity study, and no adverse events were reported (Leenhouts et al., unpublished results). Therefore, GEM particles can be considered as a safe candidate adjuvant for mucosal use in humans.

CONCLUSION

Our data show that i.n. influenza vaccine adjuvanted with GEM particles induced a comparable systemic immunity and superior mucosal and cell-mediated immunity compared to i.m. immunization with subunit influenza vaccine alone. Importantly, it induced higher sIgA levels which are a first line of defense during influenza infection in the upper respiratory tract. Moreover, it elicited a skewed Th1-type immune response which is considered to provide superior protection. Overall, GEM particles can be regarded as a safe and potent adjuvants for i.n. delivered influenza subunit vaccine.

References

WHO, influenza, fact sheet 211, revised 2003.

Couch RB, Kasel JA, Glezen WP, Cate TR, Six HR, Taber LH, et al. Influenza: its control in persons and populations. J Infect Dis. 1986;153(3):431–40.

Cox RJ, Brokstad KA, Ogra P. Influenza virus: immunity and vaccination strategies. Comparison of the immune response to inactivated and live, attenuated influenza vaccines. Scand J Immunol. 2004;59(1):1–15.

Atmar RL, Keitel WA, Cate TR, Munoz FM, Ruben F, Couch RB. A dose–response evaluation of inactivated influenza vaccine given intranasally and intramuscularly to healthy young adults. Vaccine. 2007;25(29):5367–73.

Cox RJ, Haaheim LR, Ericsson JC, Madhun AS, Brokstad KA. The humoral and cellular responses induced locally and systemically after parenteral influenza vaccination in man. Vaccine. 2006;24(44–46):6577–80.

Tamura S, Kurata T. Defense mechanisms against influenza virus infection in the respiratory tract mucosa. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57(6):236–47.

Yetter RA, Lehrer S, Ramphal R, Small PA Jr. Outcome of influenza infection: effect of site of initial infection and heterotypic immunity. Infect Immun. 1980;29(2):654–62.

Zee YC, Osebold JW, Dotson WM. Antibody responses and interferon titers in the respiratory tracts of mice after aerosolized exposure to influenza virus. Infect Immun. 1979;25(1):202–7.

Greenbaum E, Engelhard D, Levy R, Schlezinger M, Morag A, Zakay-Rones Z. Mucosal (SIgA) and serum (IgG) immunologic responses in young adults following intranasal administration of one or two doses of inactivated, trivalent anti-influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2004;22(20):2566–77.

Giudice EL, Campbell JD. Needle-free vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58(1):68–89.

Taylor HP, Dimmock NJ. Mechanism of neutralization of influenza virus by secretory IgA is different from that of monomeric IgA or IgG. J Exp Med. 1985;161(1):198–209.

Renegar KB, Small PA Jr, Boykins LG, Wright PF. Role of IgA versus IgG in the control of influenza viral infection in the murine respiratory tract. J Immunol. 2004;173(3):1978–86.

Eyles JE, Williamson ED, Alpar HO. Intranasal administration of influenza vaccines: current status. BioDrugs. 2000;13(1):35–59.

Tamura S, Funato H, Hirabayashi Y, Suzuki Y, Nagamine T, Aizawa C, et al. Cross-protection against influenza A virus infection by passively transferred respiratory tract IgA antibodies to different hemagglutinin molecules. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21(6):1337–44.

Tamura SI, Asanuma H, Ito Y, Hirabayashi Y, Suzuki Y, Nagamine T, et al. Superior cross-protective effect of nasal vaccination to subcutaneous inoculation with influenza hemagglutinin vaccine. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22(2):477–81.

Moran TM, Park H, Fernandez-Sesma A, Schulman JL. Th2 responses to inactivated influenza virus can Be converted to Th1 responses and facilitate recovery from heterosubtypic virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(3):579–85.

Liew FY, Russell SM, Appleyard G, Brand CM, Beale J. Cross-protection in mice infected with influenza A virus by the respiratory route is correlated with local IgA antibody rather than serum antibody or cytotoxic T cell reactivity. Eur J Immunol. 1984;14(4):350–6.

Tumpey TM, Renshaw M, Clements JD, Katz JM. Mucosal delivery of inactivated influenza vaccine induces B-cell-dependent heterosubtypic cross-protection against lethal influenza A H5N1 virus infection. J Virol. 2001;75(11):5141–50.

McElhaney JE. The unmet need in the elderly: designing new influenza vaccines for older adults. Vaccine. 2005;23 Suppl 1:S10–25.

Szewczuk MR, Wade AW. Aging and the mucosal-associated lymphoid system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1983;409:333–44.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of influenza vaccination target population sizes in 2006 and recent vaccine uptake levels. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/pdf/targetpopchart.pdf.

Belshe RB, Ambrose CS, Yi T. Safety and efficacy of live attenuated influenza vaccine in children 2–7 years of age. Vaccine. 2008;26 Suppl 4:D10–6.

Matassov D, Cupo A, Galarza JM. A novel intranasal virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine designed to protect against the pandemic 1918 influenza A virus (H1N1). Viral Immunol. 2007;20(3):441–52.

Joseph A, Itskovitz-Cooper N, Samira S, Flasterstein O, Eliyahu H, Simberg D, et al. A new intranasal influenza vaccine based on a novel polycationic lipid—ceramide carbamoyl-spermine (CCS). I. Immunogenicity and efficacy studies in mice. Vaccine. 2006;24(18):3990–4006.

Haan L, Verweij WR, Holtrop M, Brands R, van Scharrenburg GJ, Palache AM, et al. Nasal or intramuscular immunization of mice with influenza subunit antigen and the B subunit of Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin induces IgA- or IgG-mediated protective mucosal immunity. Vaccine. 2001;19(20–22):2898–907.

Plante M, Jones T, Allard F, Torossian K, Gauthier J, St-Felix N, et al. Nasal immunization with subunit proteosome influenza vaccines induces serum HAI, mucosal IgA and protection against influenza challenge. Vaccine. 2001;20(1–2):218–25.

Fujihashi K, Koga T, van Ginkel FW, Hagiwara Y, McGhee JR. A dilemma for mucosal vaccination: efficacy versus toxicity using enterotoxin-based adjuvants. Vaccine. 2002;20(19–20):2431–8.

Mutsch M, Zhou W, Rhodes P, Bopp M, Chen RT, Linder T, et al. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell's palsy in Switzerland. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):896–903.

Van Roosmalen ML, Kanninga R, El Khattabi M, Neef J, Audouy S, Bosma T, et al. Mucosal vaccine delivery of antigens tightly bound to an adjuvant particle made from food-grade bacteria. Methods. 2006;38(2):144–9.

Bosma T, Kanninga R, Neef J, Audouy SA, van Roosmalen ML, Steen A, et al. Novel surface display system for proteins on non-genetically modified gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(1):880–9.

Audouy SA, van Roosmalen ML, Neef J, Kanninga R, Post E, van Deemter M, et al. Lactococcus lactis GEM particles displaying pneumococcal antigens induce local and systemic immune responses following intranasal immunization. Vaccine. 2006;24(26):5434–41.

Audouy SA, van Selm S, van Roosmalen ML, Post E, Kanninga R, Neef J, et al. Development of lactococcal GEM-based pneumococcal vaccines. Vaccine. 2007;25(13):2497–506.

Ramasamy R, Yasawardena S, Zomer A, Venema G, Kok J, Leenhouts K. Immunogenicity of a malaria parasite antigen displayed by Lactococcus lactis in oral immunisations. Vaccine. 2006;24(18):3900–8.

Amorij JP, Saluja V, Petersen AH, Hinrichs WL, Huckriede A, Frijlink HW. Pulmonary delivery of an inulin-stabilized influenza subunit vaccine prepared by spray-freeze drying induces systemic, mucosal humoral as well as cell-mediated immune responses in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2007;25(52):8707–17.

Amorij JP, Westra TA, Hinrichs WL, Huckriede A, Frijlink HW. Towards an oral influenza vaccine: comparison between intragastric and intracolonic delivery of influenza subunit vaccine in a murine model. Vaccine. 2007;26(1):67–76.

Amidi M, Romeijn SG, Verhoef JC, Junginger HE, Bungener L, Huckriede A, et al. N-trimethyl chitosan (TMC) nanoparticles loaded with influenza subunit antigen for intranasal vaccination: biological properties and immunogenicity in a mouse model. Vaccine. 2007;25(1):144–53.

Sanders MT, Deliyannis G, Pearse MJ, McNamara MK, Brown LE. Single dose intranasal immunization with ISCOMATRIX vaccines to elicit antibody-mediated clearance of influenza virus requires delivery to the lower respiratory tract. Vaccine. 2009;27(18):2475–82.

Hagenaars N, Mastrobattista E, Glansbeek H, Heldens J, van den Bosch H, Schijns V, et al. Head-to-head comparison of four nonadjuvanted inactivated cell culture-derived influenza vaccines: effect of composition, spatial organization and immunization route on the immunogenicity in a murine challenge model. Vaccine. 2008;26(51):6555–63.

Coucke D, Schotsaert M, Libert C, Pringels E, Vervaet C, Foreman P, et al. Spray-dried powders of starch and crosslinked poly(acrylic acid) as carriers for nasal delivery of inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27(8):1279–86.

Verweij WR, de Haan L, Holtrop M, Agsteribbe E, Brands R, van Scharrenburg GJ, et al. Mucosal immunoadjuvant activity of recombinant Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and its B subunit: induction of systemic IgG and secretory IgA responses in mice by intranasal immunization with influenza virus surface antigen. Vaccine. 1998;16(20):2069–76.

The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP). Note for guidance on harmonization of requirements for influenza vaccines. CPMP/BWP/214/96, London, March 12, 1997.

Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. Mucosal immunity and vaccines. Nat Med. 2005;11(4 Suppl):S45–53.

Bienenstock J, McDermott MR. Bronchus- and nasal-associated lymphoid tissues. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:22–31.

Bungener L, Geeraedts F, Ter Veer W, Medema J, Wilschut J, Huckriede A. Alum boosts TH2-type antibody responses to whole-inactivated virus influenza vaccine in mice but does not confer superior protection. Vaccine. 2008;26(19):2350–9.

Geeraedts F, Bungener L, Pool J, ter Veer W, Wilschut J, Huckriede A. Whole inactivated virus influenza vaccine is superior to subunit vaccine in inducing immune responses and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by DCs. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2008;2(2):41–51.

Guy B. The perfect mix: recent progress in adjuvant research. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(7):505–17.

Hovden AO, Cox RJ, Haaheim LR. Whole influenza virus vaccine is more immunogenic than split influenza virus vaccine and induces primarily an IgG2a response in BALB/c mice. Scand J Immunol. 2005;62(1):36–44.

Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD. Influenza virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: a correlate of protection and a basis for vaccine development. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18(6):529–36.

Hagenaars N, Mastrobattista E, Verheul RJ, Mooren I, Glansbeek HL, Heldens JG, et al. Physicochemical and immunological characterization of N, N, N-trimethyl chitosan-coated whole inactivated influenza virus vaccine for intranasal administration. Pharm Res. 2009;26(6):1353–64.

Hu KF, Lovgren-Bengtsson K, Morein B. Immunostimulating complexes (ISCOMs) for nasal vaccination. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;51(1–3):149–59.

Ko SY, Ko HJ, Chang WS, Park SH, Kweon MN, Kang CY. alpha-Galactosylceramide can act as a nasal vaccine adjuvant inducing protective immune responses against viral infection and tumor. J Immunol. 2005;175(5):3309–17.

Garmise RJ, Staats HF, Hickey AJ. Novel dry powder preparations of whole inactivated influenza virus for nasal vaccination. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2007;8(4):E81.

Mercenier A, Muller-Alouf H, Grangette C. Lactic acid bacteria as live vaccines. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2000;2(1):17–25.

Seegers JF. Lactobacilli as live vaccine delivery vectors: progress and prospects. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20(12):508–15.

Acknowledgments

We thank Solvay Pharmaceuticals for providing the subunit influenza vaccine.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Saluja, V., Amorij, J.P., van Roosmalen, M.L. et al. Intranasal Delivery of Influenza Subunit Vaccine Formulated with GEM Particles as an Adjuvant. AAPS J 12, 109–116 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-009-9168-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-009-9168-2