Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals faced psychological stress caused by fear and anxiety due to the high transmission and mortality rate of the disease, the social isolation, economic problems, and difficulties in reaching health services. Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic centralized pain sensitivity disorder. Psychological, physical and/or autoimmune stressors were found to increase FM symptoms. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the COVID-19 fear and anxiety level, and to examine their effect on disease severity, sleep quality, and mood in FM patients compared to control group.

Methods

This pilot study conducted as a cross-sectional study, and included 62 participants. Participants were divided into two groups: FM patient group (n = 31) and control group (n = 31). Symptom severity, sleep quality, and mood were determined using the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR), Pitsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS), respectively. In order to evaluate the level of COVID-19 fear and anxiety, the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) and Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS) were used compared to control group.

Results

FIQR, PSQI, HAD-A, HAD-D, FCV-19S and CAS scores were significantly higher in the FM group (p = 0.01). A positive significant correlation was found between FCV-19S and CAS results and FIQR, PSQI, and HAD-anx results in FM patients (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

This pilot study showed that, the individuals with FM can be more affected by psychological stress, and this situation negatively affects the symptom severity, sleep quality, and mood in FM patients, so these patients should be closely monitored in terms of psychological stressors and their effects during pandemics. More studies with more participants are necessary to describe the challenges lived by fibromyalgia population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) announced the start of an epidemic related to the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) that caused viral pneumonia in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Since then, COVID-19 has spread all over the world and WHO declared it to be a pandemic in March 2020 [1]. Previous studies have shown that individuals’ well-being was adversely affected by prior pandemic periods [2,3,4]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals faced psychological stress caused by fear and anxiety due to the high transmission and mortality rate of the disease, the social isolation which resulted from quarantine to prevent rapid transmission, economic problems, and difficulties in reaching health services [5, 6]. Previous studies have found an increase in mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic [5,6,7].

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic centralized pain sensitivity disorder with widespread, wandering, increasing-decreasing pain attacks accompanied by fatigue, sleep disturbance, mood disorders, and somatic symptoms [8]. In controlled studies in the literature, psychological, physical and/or autoimmune stressors were found to increase FM symptoms [9]. Anxiety and psychological stress cause an increase in symptom severity in FM patients and adversely affect their quality of life [10, 11].

There are studies in the literature examining the effect of the lockdown period on FM symptoms but there is no study examining the effect of COVID-19 fear and anxiety in FM patients (disease severity, sleep quality, and mood) [9, 12]. Therefore, our study aimed to evaluate the COVİD-19 fear and anxiety level, and to examine their effect on disease severity, sleep quality, and mood in FM patients.

Materials-method

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the local institutional ethics committee of our hospital (Approval number: 102/17) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Signed informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to data collection.

Study design and participants

This pilot study conducted as a cross-sectional study, and included 62 participants. Participants were divided into two groups as the FM patient group (n = 31) and control group (n = 31). The FM group included patients between the ages of 18–65, who applied to the physical medicine and rehabilitation outpatient clinic between December 15, 2020, and February 1, 2021, who had been diagnosed with primary FM for more than 1 year according to the 2016 American College of Rheumatology criteria, and who had not been changed drug or dose for 3 months, and who had been clinically stable for at least 3 months. Patients with secondary FM or was changed drug or dose within 3 months, mood disorders, history of medication with any antidepressant or anxiolytic drugs, advanced musculoskeletal problems, additional rheumatologic diseases, COVİD-19 infection history, severe metabolic, endocrine, cardiovascular, pulmonary, genitourinary, gastrointestinal, progressive or non-progressive central or peripheral neurological diseases; and patients who underwent some type of therapy like yoga, meditation or other alternative therapies were not included in the study. The control group was selected from healthy volunteers (relatives or clinic staff) with no manifestation of disease and ages between the ages of 18–65.

Data collection

Data related to demographic characteristics such as age, gender, height, weight, body mass index, professions, educational status, and marital status were obtained from the participants. In addition, symptom severity, sleep quality, and mood were determined using the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR), Pitsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS), respectively. In order to evaluate the level of COVID-19 fear and anxiety, the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) and Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS) were used.

Revised fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQR)

FIQR was used to evaluate FM physical functionality and the severity of its symptoms. The questionnaire focuses on three areas including function, overall impact, and symptoms. The total score ranges from 0 to 100, and higher scores indicate worse functionality and increased symptom severity [13].

Hospital anxiety depression scale (HADS)

HADS is a scale developed specifically to evaluate mood disorders such as anxiety and depression. The scale includes a total of 14 questions, 7 of which belong to the anxiety subscale, and the remaining 7 questions belong to the depression subscale. Each question is scored between 0 and 3, and both the depression and anxiety subscale scores range from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety and depression [14].

Pitsburg sleep quality index (PSQI)

The PSQI is a scale consisting of 19 self-reported questions and 7 items that evaluate sleep quality. The total score of the survey is obtained from the sum of the 7-item scores. The scores range from 0 to 21, and lower scores indicate better sleep quality [15].

Fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S)

FCV-19S is a short, 7-question questionnaire developed to evaluate the level of fear and anxiety related to COVID-19 virus. Each question is evaluated with a five-point Likert type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) [16]. The Turkish adaptation of the questionnaire was made by Satıcı et al. [17]. The cut-off value in FCV-19S is determined as 16.5, and scores higher than this value have a significant predictive power on anxiety, health-related anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder [18].

Coronavirus anxiety scale (CAS)

CAS is another 5-question questionnaire developed by Lee et al. to evaluate the psychological effects of the pandemic period. Validity and reliability checks of the Turkish adaptation of the scale have been conducted Each question is scored using a 5-point time anchored scale (0 ¼ not at all to 4 ¼ nearly every day over the last 2 weeks) [19, 20].

Comparisons

COVID-19 fear and anxiety were compared between the FM and control groups, and the relationship between the level of COVID-19 fear and anxiety and FM symptom severity, sleep quality, and mood was investigated in the FM group.

Statstical analyses

`Data analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 22.0 for Windows) software. The variables were investigated using visuals (histograms and probability plots) and Shapiro-Wilks test to determine whether they are normally distributed. In reporting descriptive statistics, data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (minimum-maximum) for continuous variables, and as frequencies and percentages (%) for nominal and categorical variables. The χ2 tests, Fisher’s exact or Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare nominal variables and categorical variables between the groups. In addition, the independent samples T tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the continuous values between the groups. The relationship between FCV-19S, CAS and FIQR, PSQI, and HADS in the FM group were examined by Spearman correlation analysis. A p-value less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of age, gender, BMI, marital status, education level, occupation, and comorbidities (p > 0.05). Table 1 shows comparison of general characteristics of the participants of the two groups.

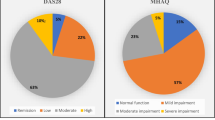

FIQR, PSQI, HADS-A, HADS-D, FCV-19S and CAS scores were significantly higher in the FM group compared to the control group (p = 0.01) (Table 2).

A positive significant correlation was found between FCV-19S and CAS results and FIQR, PSQI, and HAD-anx results in FM patients (p < 0.05) (Table 3). No significant correlation was found between the HAD-dep and FCV-19S and CAS results (r = 0.316, p = 0.084; r = 0.339, p = 0.062, respectively).

A high level of positive significant correlation was found between FCV-19S and CAS results for all patients (r = 0.778, p < 0.001).

Discussion

It was not find similar study the relates the effect of COVID-19 anxiety and fear on symptom severity, sleep quality, and mood in FM patients. The results of ongoing research revealed that the COVID-19 fear and anxiety levels in FM patients were higher than healthy patients. In FM patients, COVID-19 fear and anxiety were found to be associated with symptom severity, sleep quality, and anxiety level.

Although the cause of FM is still not fully understood, central sensitization in the central nervous system, which is associated with the development of increased sensitivity to pain signals, is the most accepted mechanism [21]. Although the main symptom of FM is pain, it is a heterogeneous picture that seriously disrupts the quality of life, including physical and mental fatigue, impaired sleep quality, headache, irritable bowel syndrome, cognitive disorders, and psychological problems [10]. The most common psychological problems in FM patients are anxiety and depression. Anxiety disorders are found in between 13 and 64% and depression in between 20 and 80% of FM patients [10]. In one study, 80% of FM patients reported poor sleep quality [22].

The whole world faced an unexpected pandemic in 2020, leading to negative psychological effects in the general population such as depression, stress, sleep disturbance, anger, and anxiety about one’s own health and the health of their relatives, phobias, and avoidance behavior [7]. Specifically, infected people, individuals with a high risk of infection (including the elderly, people with compromised immune function, and those living or cared for in public places), individuals with pre-existing medical or psychiatric illnesses, and those who had substance use problems were found to have an increased risk for adverse psychosocial outcomes [23].

During the pandemic period, new scales have been developed to evaluate the fear and anxiety associated with COVID-19 infection, which has a high transmission and mortality rate [16, 24, 25]. Among those scales, FCV-19S and CAS were used in our study. This study aimed to evaluate the level of fear and anxiety more accurately by using two separate scales and a significant correlation was found between the two scales.

Although the pandemic period has caused fear and anxiety in all individuals, previous studies have shown that those with pre-existing mood disorders were affected more by the negative psychological factors caused by the epidemic [26]. In our study, COVID-19-related fear and anxiety levels were found to be significantly higher in FM patients than the control group.

This study examined the effect of COVID-19 fear and anxiety on FM symptoms, sleep quality, and anxiety-depression levels. The results showed that COVID-19 fear and anxiety negatively affected FM symptom severity, sleep quality, and anxiety levels in FM patients.

In a study conducted by Hruschak et al., in which 150 patients with FM, chronic spine, and post-surgical chronic pain were included, patients’ self-reported pain severity was found to be higher after 4–8 weeks of social isolation compared to the pre-pandemic period. Furthermore, psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and stress were found to be associated with worse pain. In addition, the presence of FM was found to be an independent risk factor for greater pain during social isolation [27].

In a study comparing the symptom severity of FM patients in the pre-pandemic period with the lockdown period due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant difference was found in the total FIQR scores and pain, depression, and anxiety subdomains during the lockdown period compared to the pre-pandemic period. Additionally, a significant increase was found in the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 score during the lockdown period [9]. In a letter to editor, 67% of 32 FM patients reported that their general health status (well-being) worsened during the pandemic period [12].

Anxiety and depression are two closely related conditions [28]. However, our study found no relationship between depression levels and anxiety due to COVID-19. COVID-19 causes acute stress in the daily life of individuals. The severity of depression has been shown to be related to the duration of exposure to the stressor [29]. Given that our study is a cross-sectional study, more studies with longer follow-ups are needed to evaluate this relationship.

This pilot study is limited due to its small sample size and cross-sectional design.

Conclusion

Particular attention should be paid to patients with previous psychological disorders such as FM patients during pandemic periods. Because these individuals are more affected by psychological stress than other individuals, and this situation negatively affects the symptom severity, sleep quality, and mood in FM patients. The patients should be closely monitored in terms of psychological stressors and their effects especially using telemedicine applications, and necessary precautions should be taken immediately. We still continue to see the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, more studies with more participants are necessary to describe the challenges lived by fibromyalgia population.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/ (accessed 15th January 2021).

Sim K, Chua HC. The psychological impact of SARS: a matter of heart and mind. CMAJ. 2004;170(5):811–2. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1032003.

Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatr. 2009;54(5):302–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370905400504.

Kim CW, Song HR. Structural relationships among public’s risk characteristics, trust, risk perception and preventive behavioral intention: the case of MERS in Korea. Crisisnomy. 2017;13:85–95.

Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):779–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035.

Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001.

Talevi D, Socci V, Carai M, Carnaghi G, Faleri S, Trebbi E, et al. Mental health outcomes of the CoViD-19 pandemic. Riv Psichiatr. 2020;55(3):137–44. https://doi.org/10.1708/3382.33569.

Mohabbat AB, Mohabbat NML, Wight EC. Fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome in the age of COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2020;4(6):764–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.08.002.

Batres-Marroquín AB, Medina-García AC, Vargas Guerrero A, Barrera-Villalpando MI, Martínez-Lavín M, Martínez-Martínez LA. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on fibromyalgia symptoms. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;Publish Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001685.

Di Tella M, Ghiggia A, Tesio V, Romeo A, Colonna F, Fusaro E, et al. Pain experience in fibromyalgia syndrome: the role of alexithymia and psychological distress. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.080.

Galvez-Sánchez CM, Montoro CI, Duschek S, Del Paso GAR. Pain catastrophizing mediates the negative influence of pain and trait-anxiety on health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(7):1871–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02457-x.

Cavalli G, Cariddi A, Ferrari J, Suzzi B, Tomelleri A, Campochiaro C, et al. Living with fibromyalgia during the COVID-19 pandemic: mixed effects of prolonged lockdown on the well-being of patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(1):465–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa738.

Bennett RM, Friend R, Jones KD, Ward R, Han BK, Ross RL. The revised fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(4):R120. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2783.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

Climent-Sanz C, Marco-Mitjavila A, Pastells-Peiró R, Valenzuela-Pascual F, Blanco-Blanco J, Gea-Sánchez M. Patient reported outcome measures of sleep quality in fibromyalgia: a COSMIN systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):2992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17092992.

Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2020:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8.

Satici B, Gocet-Tekin E, Deniz ME, Satici SA. Adaptation of the fear of COVID-19 scale: its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2020:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0.

Nikopoulou VA, Holeva V, Parlapani E, Karamouzi P, Voitsidis P, Porfyri GN, et al. Mental health screening for COVID-19: a proposed cutoff score for the Greek version of the fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S). Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2020:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00414-w.

Evren C, Evren B, Dalbudak E, Topcu M, Kutlu N. Measuring anxiety related to COVID-19: a Turkish validation study of the coronavirus anxiety scale. Death Stud. 2020;3:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1774969.

Lee SA. Coronavirus anxiety scale: a brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud. 2020;44(7):393–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481.

Cagnie B, Coppieters I, Denecker S, Six J, Danneels L, Meeus M. Central sensitization in fibromyalgia? A systematic review on structural and functional brain MRI. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(1):68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.01.001.

Wu YL, Chang LY, Lee HC, Fang SC, Tsai PS. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. J Psychosom Res. 2017;96:89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.03.011.

Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510–2. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008017.

Lee SA, Mathis AA, Jobe MC, Pappalardo EA. Clinically significant fear and anxiety of COVID-19: a psychometric examination of the coronavirus anxiety scale. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113112.

Arpaci I, Karataş K, Baloğlu M. The development and initial tests for the psychometric properties of the COVID-19 phobia scale (C19P-S). Personal Individ Differ. 2020;164:110108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110108.

Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30090-0.

Hruschak V, Flowers KM, Azizoddin DR, Jamison RN, Edwards RR, Schreiber KL. Cross-sectional study of psychosocial and pain-related variables among patients with chronic pain during a time of social distancing imposed by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Pain. 2021;162(2):619–29. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002128.

Beard C, Millner AJ, Forgeard MJ, Fried EI, Hsu KJ, Treadway MT, et al. Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptom relationships in a psychiatric sample. Psychol Med. 2016;46(16):3359–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002300.

Ramezanzadeh F, Aghssa MM, Abedinia N, Zayeri F, Khanafshar N, Shariat M, et al. A survey of relationship between anxiety, depression and duration of infertility. BMC Womens Health. 2004;4(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-4-9.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all our participants.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each named author has substantially contributed to the research and/or drafting of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Health Sciences, Local Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval number: 102/17).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cankurtaran, D., Tezel, N., Ercan, B. et al. The effects of COVID-19 fear and anxiety on symptom severity, sleep quality, and mood in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Adv Rheumatol 61, 41 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-021-00200-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-021-00200-9