Abstract

Background

The purposes of this study were to assess the prevalence of temporomandibular disorders symptoms and signs and the bite force in pediatric patients with idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndrome and to compare to healthy control individuals paired by gender and age.

Methods

Forty consecutive patients (32 girls) from our outpatient pediatric rheumatology pain clinic with diagnosis of idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndrome were included in this study. Twenty healthy subjects (16 girls) were considered the control group. All individuals were interviewed according to a standardized questionnaire concerning the presence of orofacial pain and functional impairment, and were submitted to a clinical evaluation following a structured protocol. After that the bite force was measured.

Results

Twelve patients met the ACR criteria for fibromyalgia, and 28 presented the diagnosis of pain amplification syndrome. The mean age of patients was 13.1 years (range, 6–18 years) and of controls was 12.8 years (range, 6–18 years) with no significant difference. Orofacial symptoms occurred in 25 patients (62.5%) and in 3 controls (15%) (p = 0.0014). Sixteen (40%) patients and four (20%) controls presented pain during mandibular function with no significant difference. Although both pain groups presented separately more frequently orofacial symptoms and pain on palpation than the controls, maximal voluntary bite force was similar between patients and controls, between both patient groups and between the two pain groups and controls.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that temporomandibular disorders symptoms were more prevalent in patients with idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndrome than in healthy controls. However the bite force was not different among the groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children is common, affecting 10–20% of schoolchildren [1]. Although a serious underlying disease is not the cause in most cases, some may be life-threatening or potentially crippling [2]. A number of children may develop an idiopathic chronic musculoskeletal pain syndrome (IMPS) and become disabled [3]. This syndrome includes three entities: growing pains (limb pain), pain amplification syndrome and fibromyalgia.

Pain amplification syndrome is a condition where patients develop an abnormal pain sensitivity [4]. Fibromyalgia (FM) is currently defined as chronic widespread pain with allodynia or hyperalgesia to pressure pain [5]. FM may coexist with other clinical conditions such as temporomandibular disorders (TMD).

TMD is a term that includes clinical disorders involving the masticatory muscles, the temporomandibular joints (TMJ), and associated structures [6]. The most prevalent reported TMD’s symptoms in children and adolescents are headaches, TMJ sounds, difficulty in mouth opening, jaw and facial pain, impaired chewing ability and the most common clinical signs of TMD are TMJ and muscle tenderness, limitation of mandibular movements, and TMJ sounds [7].

It has been shown that adult patients with FM have a high prevalence of orofacial signs and symptoms, ranging from 33 to 97% [8,9,10,11].

Bite force (BF) is an indicator of the functional state of the masticatory system in children, and can be considered one of the key determinants of the masticatory performance [12, 13]. Signs and symptoms of TMD have been suggested to affect BF measurements [14]. It has been reported that pain in the masticatory muscles and TMJ can cause significant changes in the maximal BF when compared to individuals without such pain [15]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study addressing BF in pediatric IMPS patients.

The objectives of the present study were to assess the prevalence of TMD symptoms and signs in pediatric patients with IMPS and controls, and to measure the BF in those patients and to compare them to healthy control individuals paired by gender and age.

Methods

Patients

This was a cross-sectional study where sixty-three consecutive patients with diagnosis of IMPS from our outpatient pain clinic in the pediatric rheumatology division were evaluated and forty were included in the final sample. IMPS was defined by the presence of generalized musculoskeletal pain in 3 or more areas of the body for at least 3 months, and these symptoms are not explained by other causes or diseases [3]. FM was characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain associated with fatigue, sleep, memory and mood issues [5] and pain amplification syndrome was defined as by the presence of musculoskeletal pain without a well-defined organic basis.

Twenty healthy subjects were considered as control group.

The inclusion criteria were patients with IMPS (FM and pain amplification syndrome) as defined in the literature [3, 5]. Healthy subjects who were referred for control orthodontic evaluation were included as control group and were gender and age matched to the patients. Other inclusion criteria for both groups were the presence of the permanent central incisors completed erupted, first permanent molars in occlusion, and the absence of dental related pain. Twenty-three patients were excluded because they presented problems with their teeth in the areas where the BF was measured.

After informed consent was obtained, demographic and clinical data were collected from the patients’ medical records.

Methods

All patients underwent a rheumatologic examination performed by a single pediatric rheumatologist, and an orofacial examination performed by a single dentist. These examinations were scheduled for the same week.

Assessment of subjective symptoms of the TMJ

The subjects were interviewed according to a standardized questionnaire concerning the presence of pain and functional impairment. Patients and their parents answered questions regarding the presence of headaches, abdominal pain, TMJ or masticatory muscle pain at rest or during functional mandibular movements, impaired maximal mouth opening and impaired chewing ability. The questions were answered by categorical (yes/no) responses.

Clinical examination

Only one blind assessor (dentist) performed the clinical evaluation following a structured protocol. The following registrations were made:

-

Maximum mouth opening between the incisal edges of the front teeth (in mm) was measured using a millimeter ruler and adjusted for overbite and open bite as necessary. The subjects were asked to open his or her mouth as widely as possible. The patients performed the movements without any help from the examiner. Limitation of opening was defined as a range of movement in the central incisor region of less than 40 mm from the fully occluded to maximal open position [16, 17].

-

Presence of pain on palpation on facial sites (6 sites):

-

Presence of tenderness on lateral digital palpation of the TMJ on either side (2 sites);

-

Presence of tenderness on digital palpation of the masseter and temporalis muscles on either side (4 sites);

-

-

Presence of pain on function: during active mandibular movements (open, laterotrusion and protrusion).

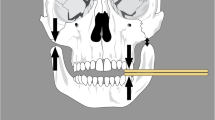

Bite force measurement

The BF registration procedure was carefully explained to all participants. Subjects sat in an upright position without head support. The BF was measured unilaterally in the area of the first permanent molars (right and left sides) and central incisors region, using a calibrated dynamometer (Crown DBC, Oswaldo Filizola, São Paulo, SP, Brazil). The stainless steel rods were 40 mm long X 12.7 mm wide X 13.5 mm thick. A piece of simple disposable foam tape (15 mm long X 13 mm wide X 4 mm tall) covered the BF application site. The peak force measurements were displayed digitally on its screen and recorded for further analysis. The dynamometer was cleaned with alcohol, a piece of sterile latex encased the device and it was replaced after each subject evaluation. Subjects were instructed to bite as hard as possible. The measurements were repeated three times, with one-minute rest between them. The highest value from the three recordings was considered as the maximal BF. The same operator performed all measurements. BF was not taken if the anterior teeth or the first permanent molars were not completely erupted or if they had had extensive restorations. The measured BF was calculated in Newton (N) and displayed digitally.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was reviewed and approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysis

In order to verify the association between the variables presence of headaches, abdominal pain, and TMD symptoms and signs in the two patient groups, Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used. These tests were also used to evaluate the association between the TMD symptoms and signs in each patient group and the control group. Student’s t-test was used to verify the variation of age, maximal mouth opening capacity, and the BF measurements between each patient group and the control group. The STATISTICA 12.7 (Dell®) program was used for the statistical analysis. The level of significance was set to 5% (p < 0.05).

Results

This study included 40 patients with IMPS. Twelve met the ACR criteria for FM (11 girls), and 28 (21 girls) presented the diagnosis of pain amplification syndrome. The mean age of patients was 13.1 years (range, 6–18 years) and of controls was 12.8 years (range, 6–18 years) with no significant difference (p = 0.464) (Table 1).

TMD symptoms occurred in 25 patients (62.5%) and in 3 controls (15%) (p = 0.0014). Sixteen (40%) patients and four (20%) controls presented pain during mandibular function (p = 0.2081). During palpation, 36 (90%) patients and only six (30%) controls complained about pain at least in one site (p < 0.0001) (Table 1). In addition, the mean measurement of the vertical range of motion of the mandible during maximum unassisted opening was 48.9 mm (ranging from 37 to 50 mm) in patients and 43.4 mm (ranging from 40 to 64 mm) in control group.

When we compared the two pain groups we observed that the FM group complained more frequently of soft tissue swelling over the TMJ (p = 0.0175). We did not find any difference in relation to the frequency of the complaint of headaches or abdominal pain between them. Both pain groups presented similar TMD signs, but there was a statistically difference between the frequency of 4 or more painful sites on palpation in FM patients compared with pain amplification syndrome patients (p = 0.0375). All other features did not present significant differences between the two patient groups (Table 2).

Each pain group presented more frequently TMD symptoms and pain on palpation than the controls (Table 3).

Maximal voluntary BF was similar between patients and controls (Table 1), between both patient groups (Table 2) and between the two pain groups and controls (Table 3).

Discussion

TMD symptoms and signs in pediatric patients with idiopathic musculoskeletal pain conditions were evaluated in this study. In this pioneer study, we observed that TMD symptoms and pain on palpation were more frequent in patients than in controls.

In relation to gender we found a greater prevalence of girls in our consecutive sample. It is known that chronic pain in females involves several factors such as behavior, hormones, morphological characteristics, and emotion. Pereira et al. showed that female adolescents are more likely to experience TMD than males [18]. It is important to note that females generally have lower pain thresholds than males [19].

FM and pain amplification syndrome patients presented more pain on palpation when compared to controls. The most important TMD feature is pain, followed by restricted mouth opening capacity and joint sounds as observed by Manfredini [20]. When we compared our findings with this study, we observed a considerable difference, mainly the absence of functional alterations such as restricted mouth opening capacity. Furthermore, we also did not find a difference in BF between patients and controls. These results were unexpected since these patients should have presented the same findings as other patients with TMD symptoms.

BF is an indicator of normal masticatory function, but many factors may influence the values found for this parameter. Facial structure, general muscular force, gender, state of dentition, and signs and symptoms of TMD are some of them [21, 22]. Lower BF was found among adolescents with TMD [23]. Kobayashi et al. did not detect an association between TMD and BF [24]. Similarly, we did not find differences between the pain of patients and controls in relation to BF, even when we compared the two patients groups with the control group and when BF was compared between the two pain conditions.

We found a high prevalence of TMD complaints in our patients with idiopathic musculoskeletal pain, however these complaints did not correspond to the clinical signs. But interestingly, although they presented pain very frequently on palpation they did not present alterations in other clinical parameters such as pain on function, limited mouth opening capacity or lower maximal BF. These findings indicate the need of functional testing for an accurate differential diagnosis with TMD and the appropriate management of those signs and symptoms. One possible explanation for this could be that individuals with idiopathic musculoskeletal pain should be considered as having a somatoform disorder. Somatisation refers to individuals who report symptoms that have no organic cause, or who report symptoms that greatly exceed those expected by the physical condition [2].

The limitations of this study are the small number of patients and the heterogeneity of clinical features that these patients present.

Health professionals who take care of children and adolescents with IMPS should always consider the subjective symptoms related to the orofacial region and the need of an accurate differential diagnosis with TMD; this could provide valuable information for the appropriate conservative management with a multidisciplinary approach.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings indicate that TMD symptoms were more prevalent in patients with IMPS than in healthy controls. However, the bite force was not different among the groups.

References

Goodman JE, McGrath PJ. The epidemiology of pain in children and adolescents: a review. Pain. 1991;46:247–64.

Malleson PN, Beauchamp RD. Diagnosing musculoskeletal pain in children. CMAJ. 2001;165:183–8.

Malleson PN, Al-Matar M, Petty RE. Idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndromes in children. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1786–9.

Sherry DD, Malleson PN. The idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndromes in childhood. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2002;28:669–85.

Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–72.

Thilander B, Rubio G, Pena L, Mayorga C. Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction and its association with malocclusion in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic study related to specified stages of dental development. Angle Orthod. 2002;72:146–54.

Vierola A, Suominen AL, Ikavalko T, Lintu N, Lindi V, Lakka HM, et al. Clinical signs of temporomandibular disorders and various pain conditions among children 6 to 8 years of age: the PANIC study. J Orofac Pain. 2012;26:17–25.

Hedenberg-Magnusson B, Ernberg M, Kopp S. Symptoms and signs of temporomandibular disorders in patients with fibromyalgia and local myalgia of the temporomandibular system. A comparative study. Acta Odontol Scand. 1997;55:344–9.

Plesh O, Wolfe F, Lane N. The relationship between fibromyalgia and temporomandibular disorders: prevalence and symptom severity. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1948–52.

Salvetti G, Manfredini D, Bazzichi L, Bosco M. Clinical features of the stomatognathic involvement in fibromyalgia syndrome: a comparison with temporomandibular disorders patients. Cranio. 2007;25:127–33.

Gui MS, Pimentel MJ, Rizzatti-Barbosa CM. Temporomandibular disorders in fibromyalgia syndrome: a short-communication. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2015;55:189–94.

Hatch JP, Shinkai RS, Sakai S, Rugh JD, Paunovich ED. Determinants of masticatory performance in dentate adults. Arch Oral Biol. 2001;46:641–8.

Gavião MB, Raymundo VG, Rentes AM. Masticatory performance and bite force in children with primary dentition. Braz Oral Res. 2007;21:146–52.

Pereira LJ, Pastore MG, Bonjardim LR, Castelo PM, Gavião MB. Molar bite force and its correlation with signs of temporomandibular dysfunction in mixed and permanent dentition. J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34:759–66.

Svensson P, Graven-Nielsen T. Craniofacial muscle pain: review of mechanisms and clinical manifestations. J Orofac Pain. 2001;15:117–45.

Sheppard IM, Sheppard SM. Maximal incisal opening—a diagnostic index? J Dent Med. 1965;20:13–5.

Agerberg G. Maximal mandibular movements in children. Acta Odontol Scand. 1974;32:147–59.

Pereira LJ, Pereira-Cenci T, Del Bel Cury AA, Pereira SM, Pereira AC, Ambosano GM, et al. Risk indicators of temporomandibular disorder incidences in early adolescence. Pediatr Dent. 2010;32:324–8.

Buskila D, Press J, Gedalia A, Klein M, Neumann L, Boehm R, et al. Assessment of nonarticular tenderness and prevalence of FS in children. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:368–70.

Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E, Piccotti F, Ahlberg J, Lobbezoo F. Research diagnostic criteria for temporo-mandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:453–62.

Kiliaridis S, Kjellberg H, Wenneberg B, Engstrom C. The relationship between bite force endurance and facial morphology during growth. A cross-sectional study. Acta Odontol Scand. 1993;51:323–31.

Sonnesen L, Bakke M. Molar bite force in relation to occlusion, craniofacial dimensions, and head posture in pre-orthodontic children. Eur J Orthod. 2005;27:58–63.

Bonjardim LR, Gaviao MB, Pereira LJ, Castelo PM. Bite force determination in adolescents with and without temporomandibular dysfunction. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:577–83.

Kobayashi FY, Gavião MB, Montes AB, Marquezin MC, Castelo PM. Evaluation of oro-facial function in young subjects with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41:496–506.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the results reported in the article can be found in an excel databasis in our unit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ colected the patients data and was the major contributor in writing the manuscript. MF and CL reviewed the manuscript. MS and CH performed the statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript. MTT analyzed and interpreted the patient data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was reviewed and approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de São Paulo.

Consent for publication

All authors signed a consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zwir, L., Fraga, M., Sanches, M. et al. A case-control study about bite force, symptoms and signs of temporomandibular disorders in patients with idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndromes. Adv Rheumatol 58, 7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-018-0006-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-018-0006-z