Abstract

Background

Wilding conifers are a major threat to large areas of land throughout New Zealand where they compete with native vegetation, modify ecosystems, reduce available grazing land, limit future land-use options and visually change landscapes. Wilding conifers can also enhance damaging fires and in water limited catchments can affect surface flows and aquifer recharge.

A range of herbicide treatments was aerially applied by boom to a field trial established within a wilding Pinus contorta (Dougl.) (height range 1.5 – 12 m) infestation. Measurements of mortality taken two years post herbicide application were used to examine variation in efficacy of these herbicides using a mixed-effects model that tested the main and interactive effects of tree height and herbicide treatment on mortality. For a treatment to be considered effective, a mortality rate of over 85% should be achieved.

Findings

Herbicide treatment was found to significantly affect mortality. Application of herbicides that included triclopyr (18 kg a.i. ha−1) and dicamba (5 kg a.i. ha−1) applied in combination or these active ingredients applied with picloram (2 kg a.i. ha−1) were found to effectively control P. contorta across the treated height range inducing respective mortality rates of 88 and 89%. Tree mortality rates for these two herbicides were significantly greater than for two treatments with only triclopyr (37%) or triclopyr and picloram (66%) used at the previously stated rates. Neither height nor the interaction of height and treatment affected mortality over the tested range of heights.

Conclusions

This research has shown that dense infestations of P. contorta can be successfully controlled using aerial broadcast application of triclopyr-based herbicides applied in a high volume (400 L ha−1) mixture, with extremely large droplets (400 – 500 μm). The Department of Conservation has adopted the most effective formulation for operational use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Exotic conifer species were planted for erosion control, research, shelter, landscaping and production forests from the late 1880s onwards (Ledgard 2001) throughout New Zealand. Most of these conifers are primary colonisers and have naturally regenerated from these plantings. These conifers, known as wildings, have spread extensively since then, and the total area in which wilding conifers occur in the South Island of New Zealand is estimated to be in excess of 500,000 ha (Raal and Gous 2010). Wilding conifers occur within more than 200,000 hectares of land administered by the Department of Conservation (DOC), of which approximately two thirds is invaded by Pinus contorta (Dougl.) (Ledgard 2001).

Wilding conifers are controlled either by mechanical (brush cutters and chainsaws), physical (hand pulling and slashing) or chemical (herbicides) methods. For dense infestations (greater than 80% canopy cover), aerial boom spray applied chemical control is a cost effective and practical solution (Raal and Gous 2010). However, the feasibility of boom sprayed chemical control for invasive wilding conifers in New Zealand has had variable success to date (Raal and Gous 2010).

Potential herbicides for controlling wildings have been identified through pot trials (Gous 2010a, 2010b). The selective and systemic herbicides triclopyr ester (3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyloxyacetic acid) and picloram (4-amino-3,5,6-trichloropicolinic acid), applied alone (triclopyr ester) or in combination (triclopyr ester and picloram) and the non-selective systemic combination of glyphosate (N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine) and metsulfuron (2-[[[(4-methoxy-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)amino]-oxomethyl]sulfamoyl]benzoic acid methyl ester) provided best control of small (height of ~0.3 m) P. contorta, P. mugo (Turra) and Pseudotsuga mensiesii (Mirb.).

Although these herbicides have been shown to be effective on young juvenile conifers (Gous 2010a, 2010b), little research has been conducted using these herbicides on mature conifers, growing in dense infestations where trees can reach heights of up to 15 m. Recent research shows that these herbicides have low efficacy (≤64% mortality) on large wilding P. contorta (height range 1 − 15 m) and P. mugo (height range 0.5 − 5 m) when they are mixed with water and aerially applied at low rates (150 L ha−1) (Gous et al. 2014). Gous et al. (2014) concluded that application rates of water had to be high enough to ensure complete coverage of the foliage. As a consequence of these results, the objective of this research was to examine the efficacy of a range of systemic herbicides, applied in high water rates (400 L ha−1), with wetting agents, to control dense field infestations of P. contorta.

Methods

Sites, treatments and application

The site selected for the P. contorta trial was located at Ferintosh Station (latitude 44° 6' 00'' S; longitude 170° 07' 29''), near Twizel, New Zealand. The herbicide treatments were applied as water-based mixtures at 400 L ha−1 using a calibrated helicopter boom spray and an extremely coarse (ASABE 2009) droplet spectrum of approximately 400 - 500 μm, that was determined by the manufacturer using tests with water. Application was undertaken with a MD 520N helicopter, flying at a ground speed of 33 knots with a release height of 10 m above the tree canopy. Sufficient spray was carried to treat a single plot (ca. 200 litres) which was within the maximum payload of 400 – 500 litres of the MD 520N helicopter.

The helicopter was fitted with 45 × AIC 11010 nozzles (Spraying Systems Co 2006), orientated straight back, at an angle of 0°, evenly spaced along the boom to within 80% of the rotor diameter. At the ground speed at which the helicopter was flown, the required flow rate was 163 L min−1. This is equivalent to a flow rate of 3.6 L min−1 nozzle−1 and is delivered at a pressure of ca. 2.5 bar. Flying height and the flight lane separation of 4 m was measured and maintained by global positioning system (GPS) and spray-system navigation equipment.

Four treatments (Table 1) were selected based on results from previous herbicide screening and field trials (Gous 2010a, 2010b; Gous et al. 2014). These treatments were based on triclopyr ester and included combinations of this active ingredient with picloram and dicamba (Table 1) (AgriMedia Ltd 2010). Ammonium sulfate, Kwickin spray oil (Surface Science Technology, Auckland, New Zealand) and Companion surfactant (Surface Science Technology, Auckland, New Zealand) were added to the spray solution to enhance herbicide uptake (Nalewaja and Matysiak 1993) and increase canopy coverage. Each treatment was applied to three replicate 0.5 ha treatment plots using a randomised complete block design. A control of three replicate 0.5 ha plots, that received no treatment was also included in the design.

Treatments were applied on 14 December 2010, during the period of active growth to promote the uptake and translocation of herbicide throughout the trees (Radosevich and Bayer 1979). Mean tree heights at the time of treatment ranged from 1.5 – 12.0 m (Table 2). The range in tree height was similar for all treatments (Table 2).

Damage assessment

Thirty-three trees were randomly selected from each treatment plot and marked for subsequent assessment of damage. Tree mortality was recorded two years following the treatment as the percentage dead foliage in increments of 10%. The crown of each tree was visually assessed from the ground by dividing it into three equal sections from top to bottom, and each section scored individually, then averaged to obtain a whole-tree score. A tree with 100% dead foliage was scored as dead. A treatment was considered effective when a mortality rate of over 85% was reached. Tree height was measured using a Suunto clinometer (Suunto, Vantaa, Finland).

Analysis

All analyses were undertaken using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc. 2008). Percentage mortality was the dependent variable used in analyses and this variable was transformed for analysis using an arcsine square root transformation to meet the underlying assumptions of the models used. Within each plot, mean mortality in 2 m height classes was used within analyses so that the effects of treatment and tree height on mortality could be examined.

Using this data, a mixed-effects model was used to test the effects of treatment, height class and the interaction between treatment and height class on transformed mortality. Replicate was included in the model as a random effect while treatment and height class were treated as fixed effects. All variables were included within the model as class-level variables. Where the treatment effect was significant, multiple comparisons were undertaken by examining the significance of least square differences using a t-test.

Findings

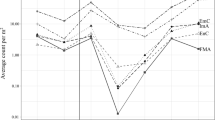

No mortality (0%) was recorded for the control treatment. Analyses showed herbicide treatment to have a strong significant effect on mortality (Table 3). Neither height class nor the interaction between height class and treatment were significant (Table 3) indicating that changes in mortality across height classes were relatively similar between treatments.

The treatment containing triclopyr, dicamaba and picloram induced the highest mortality of the four tested herbicide combinations (Table 4). However, it is worth noting that there was no significant difference in mortality between this treatment and the treatment with only triclopyr and dicamba (89 vs 88%) suggesting that addition of picloram had little impact on tree mortality. Triclopyr, dicamba and picloram have little effect on monocotyledon plants, therefore the use of these herbicides may promote re-establishment of treated areas into native tussocks in areas where grassland is the dominant vegetation. The inclusion of picloram within the mixture may be beneficial as this active ingredient has long persistence and activity in the soil compared with triclopyr and dicamba. Previous research has shown that picloram has residual soil activity of up to 450 days after treatment (MacDiarmid 1975) which may provide an extended period over which germinating conifer seed and the wilding conifer can be killed.

Either an application of triclopyr alone or a mixture of triclopyr and picloram without dicamaba was significantly less effective at controlling P. contorta (inducing respective mortality of 66 and 37%) than the treatment containing triclopyr, picloram and dicamaba, where mortality was 89% (Table 4). These results suggest that dicamba is a far more effective mixing partner than picloram in herbicide mixtures with triclopyr.

In conclusion, this research showed that dense infestations of P. contorta can be successfully controlled using aerial broadcast application of triclopyr-based herbicides applied in a high volume (400 L ha−1) mixture, with extremely large droplets (400 – 500 μm). On the basis of this research, the Department of Conservation is operationally using the triclopyr, picloram and dicamaba formulation.

References

AgriMedia Ltd. (2010). New Zealand Novachem Agrichemical Manual. New Zealand: Christchurch.

ASABE (2009). ASABE - S572.1, Spray nozzle classification by droplet spectra. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers.

Gous, SF, Watt, MS, Richardson, B, & Kimberley, MO. (2010a). Herbicide screening pot trial for wildling conifer control (Pinus contorta, P. mugo and Pseudotsuga menziesii). New Zealand Journal of Forestry, 55, 11–14.

Gous, SF, Watt, MS, Richardson, B, & Kimberley, MO. (2010b). Herbicide screening trial to control dormant Pinus contorta, P. mugo and Pseudotsuga menziesii during winter. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 40, 153–159.

Gous, S, Raal, P, & Watt, MS. (2014). Dense wilding conifer control with aerially applied herbicides in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 44, 4.

Ledgard, N. (2001). The spread of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta, Dougl.) in New Zealand. Forest Ecology and Management, 141, 43–57.

MacDiarmid, BN. (1975). Soil residues of picloram applied aerially to New Zealand brushweeds. Proceedings of the New Zealand Weed and Pest Control Conference, 28, 109–114.

Nalewaja, JD, & Matysiak, R. (1993). Influence of diammonium sulfate and other salts on glyphosate phytotoxicity. Pesticide Science, 38(2–3), 77–84. doi:10.1002/ps.2780380203.

Raal, P, & Gous, SF. (2010). Literature Review of Herbicides to Control Wilding Conifers. (Scion report no. 17750). Rotorua, New Zealand: Scion.

Radosevich, SR, & Bayer, DE. (1979). Effect of temperature and photoperiod on triclopyr, picloram and 2,4,5-T translocation. Weed Science, 27, 22–27.

SAS Institute Inc. (2008). SAS/STAT 9.2 User’s Guide. Cary NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Spraying Systems Co. (2006). Teejet Catalog 50-M. IL, USA: Wheaton.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the FRST contract Beating Weeds 2 (Contract No. C09X0905). Thanks to Peter Willemse, Department of Conservation, Twizel, for taking care of all logistics, i.e. site selection, herbicide delivery and helicopter availability.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SG was the primary author and co-designed the study. PR undertook all field measurements and co-designed the trial. MSW was the secondary author and undertook all analyses. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gous, S., Raal, P. & Watt, M.S. The evaluation of aerially applied triclopyr mixtures for the control of dense infestations of wilding Pinus contorta in New Zealand. N.Z. j. of For. Sci. 45, 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40490-014-0031-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40490-014-0031-6