Abstract

In this study, we estimate final demand for beverages with a particular focus on alcoholic beverages and calculate elasticities using microdata from the Swiss household expenditure survey from 2000 to 2009, which containsdata from more than 34,000 households. We estimate price and income responses for three household segments — light, moderate, and heavy drinking households — to assess whether higher alcohol consumption could be described by different price and income elasticities in comparison to lower alcohol consumption. We obtain unconditional estimates by applying a two-stage budgeting quadratic almost ideal demand system. To generate missing price data, we used the recently proposed quality adjusted price approach. Due to a high share of zero consumption for some beveragescategories,we correct the model with a two-step estimation procedure. Estimation results show that heavy drinking households are much less price elastic with respect to wine and beer in comparison to moderate or light drinking households, while the price response for spirits is almost constant over the three segments. Before implementing a new tax for alcoholic beverages in Switzerland, the social, health, and economic effects of a rather small decrease in alcohol consumption among heavy drinking households must be weighed against possible negativeconsequences of a sharp decline in light or moderate drinking households.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Knowledge about the determinants of consumption of alcoholic beverages and the price and income elasticity of different consumer segments is highly relevant to policy decisions. Alcohol consumption is a public health priority. Following for example Wakabayashi ([2013]) and Corrao et al. ([2000]), a regular but moderate consumption of alcohol in general can have a positive effect on health by increasing the level of HDL cholesterol and reducing the risk of heart and vascular diseases, though other studies do not report positive health effects of low or moderate alcohol consumption (Estruch et al. [2014], WHO [2007]). The discussion is complex and still ongoing. However, there is consensus that excessive alcohol consumption can be detrimental to health in that it can lead to liver cancer, liver disease, higher blood pressure, stroke, or mental decline (Rehn et al. [2001]; Schwartz et al. [2013]; Sabia et al. [2014]). In addition, excessive alcohol consumption can also have negative psychological and behavioral consequences. It can lead to higher rates of crime or violence (Jacobs and Steyn [2013]; Fergusson et al. [2013]) and have negative economic effects, leading to substantial higher state costs (Sacks et al. [2013]).

Policy measures have been shown to reduce alcohol consumption and to be a cost effective health care intervention (Xuan et al. [2013]; Doran et al. [2013]). Nevertheless, alcohol taxation and its effectiveness is still a controversial discussion point in Switzerland and other European countries (for an overview of the different alcohol policy regulations in Europe see e.g., FOPH, [2014a]). While total alcohol consumption in Switzerland has been decreasing slightly since 1990, with a current per capita consumption of about 8.5 liters of pure alcohol per year (SAB [2013]), excessive forms of alcohol drinking like binge drinking have been increasing, especially among young people (FOPH [2013]; Annaheim and Gmel [2004]). Therefore, Switzerland is currently debating a tightening of alcohol legislation. While wine is excluded from the alcohol tax, beer and spirits are heavily taxed. The current legislation has the purpose of a positive health effect on one hand and a fiscal benefit on the other, with annual tax revenue of about 440 million Swiss francs (FDF [2009]).

In order to assess the effect of a new tax on consumption, especially in the case of heavy drinkers, the estimation of price elasticities is crucial. However, price policies may be superfluous if changing income level affects consumption (Aepli and Finger [2013]; Gallet [2010]). Therefore, an estimation of income elasticities as a supplement to price elasticities is necessary. An additional tax burden to reduce light or moderate drinkers’ consumption levels may not be desirable with respect not only to social aspects but also concerning health effects, depending on which assumptions are made with respect to the health effects of low or moderate alcohol consumption. In the case of heavy drinkers it is clear that a reduction in consumption would reduce public health costs and decrease social problems. To address the question of how price and income affect demand for alcoholic beverages in Switzerland, we estimate final demand price and income elasticities separately for light, moderate, and heavy drinking households based on a repeated cross-sectional household expenditure survey. We combine several recently used methods into one demand system, expecting that price and income responses are not constant among the three segments. Switzerland is a particularly interesting case due to its comparatively high purchasing power. Findings from the Swiss case can also be transferred to a considerable extent to other European countries.

Elasticity estimates based on household data are scarce. Most studies rely on time-series data (Gallet [2007]), which limits the ability to estimate elasticities for different household segments. Furthermore, most studies did not investigate possible substitution effects between alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages. Our study contributes to filling this gap and allows a more detailed understanding of alcohol demand with respect to the demand response of different household segments.

We apply a two-stage quadratic almost ideal demand system (QUAIDS) (Banks et al. [1997] [for application see e.g., Abdulai [2002]; Jithitikulchai [2011]). It uses cross-sectional data from the Swiss household expenditure survey from 2000 to 2009, which contains data from more than 34,000 households. Final demand elasticities are estimated for food, beverages, and other products and services at the first stage and for wine, beer, spirits, and several non-alcoholic beverages at the second stage. Due to a high zero consumption for some product groups, we modified the QUAIDS using Shonkwiler and Yen’s approach ([1999]) (for application see e.g., Thiele [2008]; Tafere et al. [2010]) and corrected for possible heteroscedasticity by applying a parametric bootstrap. We received missing price data by using the method recently proposed by Majumder et al. ([2012]), further developed by Aepli and Finger ([2013]), and by introducing a variable for seasonality and trend applied by Aepli and Kuhlgatz ([2014]) for the same expenditure survey. Furthermore, we corrected for endogeneity of the expenditure variable in the model by using the augmented regression technique.

Heeb et al. ([2003]) analyzed the effect in Switzerland of a price reduction on spirits in 1999. The reduction was due to a tariff reduction under the WTO agreement and they focused on heavy drinkers using a longitudinal survey. Overall, spirits are rated as inelastic, whereas low volume drinkers are more elastic than high volume drinkers are. This would mean that taxes should reduce light or moderate drinkers’ level of consumption more than the heavy drinkers’ levels (Manning et al. [1995]). Kuo et al. ([2003]) used the same period as Heeb et al. ([2003]) with the price reduction due to the WTO agreement to estimate demand reaction to the price decrease. They found that young people in particular responded with higher demand, whereas people aged 60 or older did not respond at all to the price change.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section Theoretical framework and two-stage budgeting, we describe the theoretical framework and the two-stage budgeting system, and in Section Data description and price computation, we present the descriptive statistics and indicate how price data are generated. Section Estimation procedure and elasticity calculation summarizes the estimation procedure and the elasticity calculation. The income and price responses are discussed in Section Results and discussion, while Section Conclusions and policy implications concludes.

Background

Theoretical framework and two-stage budgeting

Theoretical framework of the QUAIDS

Equation systems have been widely used in demand analysis. The most frequently applied models are: the almost ideal demand system (AIDS) or the linearized AIDS (Deaton and Muellbauer [1980a], [1980b]; Akbay et al. [2007]; Mhurchu et al. [2013]); the quadratic version of the AIDS (QUAIDS) (Banks et al. [1997]; Abdulai [2002]; Dey et al. [2011]; see Stasi et al. [2010] and Cembalo et al. [2014] for wine in particular); the Rotterdam model (Barten [1964]; Theil [1965]; Barnett and Seck [2008]; Barnett and Kanyama [2013]); the Translog (Christensen et al. [1975]; Holt and Goodwin [2009]); and the linear and quadratic expenditure systems (Pollak and Wales [1978]; De Boer and Paap [2009]). One of the most important criteria is the approximation of non-linear Engel curves, which is best satisfied by the QUAIDS and allows general income responses that are not captured by the AIDS or many other models. The QUAIDS model is a rank three demand system and satisfies the axioms of choice. It allows exact aggregation over consumers due to underlying preferences that are of the generalized Gorman polar form (Banks et al. [1997]; Blackorby et al. [1978]). The recently proposed EASI demand system (Lewbel and Pendakur [2009]; for application see e.g., Stasi et al. [2011]) would have been an alternative due to its flexibility with respect to the approximation of Engel curves. But Cranfield et al. ([2003]) noted that the QUAIDS is especially suitable in the case of a disaggregated analysis, as in this study. Furthermore, the QUAIDS has already been successfully applied to the Swiss household expenditure survey (see e.g., Abdulai [2002]).

Following Banks et al. ([1997]) the indirect utility function of the QUAIDS is given by:

where m is total expenditure and p are prices, a(p) is the translog price aggregator, and b(p) is the Cobb-Douglas price aggregator. The term is the indirect utility function of a PIGLOG demand system and λ(p) is a differentiable, homogeneous function of degree zero of prices. a(p) and b(p) are defined as follows:

where i and j are specific goods and n is the number of goods.

The Marshallian demand function in budget shares is obtained by applying Roy’s identity to the indirect utility function:

where w i is the budget share for product category i, and α 0, α i , γ ij , β i and λ i are parameters to be estimated. The residuals ε i are assumed to be multivariate normal distributed with zero mean and a finite variance-covariance matrix.

To meet utility maximization theory, the restriction of adding-up (5), of homogeneity of the Marshallian cost function in prices and total expenditure (6), and of symmetry of the Slutsky matrix (Young’s theorem) (7) are implemented:

Theoretical restrictions allow us to reduce the number of estimated parameters as well as improve the efficiency of the estimated model (Barnett and Seck [2008]). To avoid singularity in the variance-covariance matrix and to satisfy the condition of adding-up, one equation is dropped and an n-1 equation system is estimated. The parameters of the n th equation are obtained from the restriction and the parameters of the n-1 equations.

In addition to the economic determinants, we take household characteristics and a variable for seasonality and time trend into account using the demographic translation approach by Pollak and Wales ([1978]) (applied e.g., by Abdulai [2002]; Bopape and Myers [2007]), modifying the intercept α 0 in equation (4) to

Where d f is the f th variable of a total number of S variables including household characteristics and a variable for month and year.

Two-stage budgeting design

To obtain unconditional elasticities for alcoholic beverages, which are more suitable for policy recommendations than conditional elasticities (Abdulai [2002], Klonaris and Hallam [2003]), we adopt a two-stage budgeting system, assuming separability of the utility function (for further explanations see e.g., Moschini et al. [1994] or Brehe [2007])a. First, we assume that the household allocates its budget on the three aggregated product groups at stage 1: food, beverages, and other products and services. At stage 2, the total expenditure for beverages is allocated to the disaggregated product categories: wine, beer, spirits, coffee, tea, cocoa beverages, mineral water, non-alcoholic soft drinks, and fruit and vegetables juices. We estimate income and price response at both stages, while the elasticity at stage 2 is conditional with respect to total expenditure for beverages. Unconditional elasticities for stage 2 could be obtained using the elasticity estimates at stage 1 (see Section Elasticity estimates).

Method and data

Data description and price computation

Summary statistics and definition of the household segments

For our study, we used data collected by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office from 2000 to 2009 for the Swiss household expenditure survey , a national representative survey that consists of cross-sectional data with a periodicity of one month. Almost 3,000 households participate in the survey every year. We can base our estimates on more than 34,000 households over a period of 10 years. Households are chosen randomly from the register or private telephone lines (see SFSO [2011] for details). The sample is stratified with respect to the seven major regions in Switzerland and the distribution of households is calibrated to the distribution of households in the Swiss population (SFSO [2011]). For every household, data on expenditure and quantity bought (in liters per month) for all products and services, household income, and detailed information on household characteristics were gathered. To increase the explanatory power of the model and to test whether household characteristics have an influence on alcohol demand, we introduced the following criteria into the model: household size in terms of adult equivalents, a dummy variable for the presence of young children (<5 years), the age of the household’s reference person, and a dummy variable for whether the household’s reference person has a university degree. Household size is calculated following the OECD-modified equivalence scale (Hagenaars et al. [1994]). Following Angulo et al. ([2001]) we expect a decreasing expenditure share as the number of equivalence increases and the household’s reference person’s age decreases. With respect to education and the presence of young children there are either contradictory or no clear findings in the literature (see e.g., Van Oers et al. [1999]; Reavley et al. [2011]; Rice et al. [1998]).

The sample is divided into three segments: light drinking households, moderate drinking households, and heavy drinking households. We provide elasticities for the entire sample as well as for the three household segments. The classification is constructed based on the recommendations for Switzerland in Annaheim and Gmel ([2004]). These are the official recommendations for Switzerland from the Swiss Institute for the Prevention of Alcohol and Drug Problems. Table 1 summarizes the class boundaries in pure alcohol per person and day.

According to FOPH ([2014b]), we assume the following levels of pure alcohol for each beverage category: 86.9 g pure alcohol per liter for wine, 37.9 g pure alcohol per liter for beer, and 316.0 g pure alcohol per liter for spirits. We calculated the amount of pure alcohol bought per month for every household based on data from the household expenditure survey. We divided the total amount of pure alcohol by the adult equivalent for every householdb and classified the households according to the class boundaries (Table 1) based on Annaheim and Gmel’s recommendations (2004).

Tables 2, 3 and 4 present summary statistics for stage 1, stage 2, and the household characteristics considered in the model. Furthermore, we provide the share of zero consumption for every product group. Given that some households did not buy beverages during the collection period, the sample for stage 2 declines to 33,364 households.

As Table 2 demonstrates, Swiss households spend only 1.4% of their budget on beverages, with 0.8% on alcoholic beverages and 0.7% on non-alcoholic beverages (Table 3). This is much lower than the European Union average values of about 1.5% and 1.2% of household budgets spent on alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, respectively (Eurostat [2013]). Within alcoholic beverages, the highest share of the Swiss budget is spent on wine, followed by spirits and then beer. Table 3 clearly delineates the differences among the three household segments. Moderate drinking households spend on average four to five times more on wine, beer, or spirits than light drinking households, whereas heavy drinking households spend about twice as much or more in comparison to moderate drinking households. On average, the light drinking household consumes 49.3 g of pure alcohol per month, the moderate drinking household 864.5 g, and the heavy drinking household consume 1890.0 g.

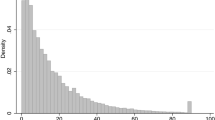

The share of zero consumption is a point of particular interest. Zero consumption means that the left side of equation (4) (budget share) is left censored at zero in the case of demand systems. Besides a short collection period, which may play a special role in the context of beverages, there are other determinants for zero consumption like income restrictions that force households into a corner solution or forgoing preferences for certain products (see e.g., Perali and Chavas [2000]; Thiele [2008]). On the aggregated level (stage 1), zero consumption is low, but at the stage 2 level, a large proportion of households did not consume at all during the collection period. This has serious implications for the model specification. Censoring of the expenditure data should therefore be considered, in particular at stage 2, to avoid biased parameter estimates.

Quality-adjusted prices

Only a few household expenditure surveys collect price data. In the literature, there are two main methods for retrieving price data from expenditure and quantity variables: using unit values as proxy for market prices, as Abdulai ([2002]) or Akbay et al. ([2007]) did by dividing the expenditure by the quantity consumed. The other method of quality-adjusted unit values was originally introduced by Cox and Wohlgenant ([1986]) and is frequently applied in the literature (e.g., in Lazaridis [2003]; Thiele [2010]; Zheng and Henneberry [2010]). Despite the nomenclature, unit values still have a quality aspect, because of the heterogeneity of products within a given category (e.g., wine). The consumer can select between different quality levels, leading to different unit values among households; differences in unit values can be attributed to quality and price variations (Chung et al. [2005]). An increase in the unit value could be induced by a price increase or by a shift in the household’s demand for more expensive products within this particular product category. Thus, taking unit values as proxies for market prices could lead to biased parameter estimates. This is particularly true for composite commodities (Chung et al. [2005]), such as the beverage product groups used in this study, which contain products of varying qualities. As McKelvey ([2011]) notes, unit values will be an "error-ridden indicator of prices".

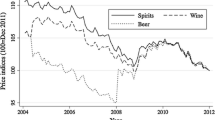

Cox and Wohlgenant ([1986]) proposed correcting the unit value for every household and product group by regressing proxies for quality variations (e.g., education or household size) on the unit value. This leads to quality-adjusted prices that vary between household. Majumder et al. ([2012]) criticized this approach, stating that households should face the same price at least in the same regional market and proposed a new method to calculate quality-adjusted prices per region. Aepli and Finger ([2013]) expanded it by a variable for month and year and adapted it for the Swiss household expenditure survey.

We give a short overview of the method (for further details, see Majumder et al. ([2012]) and Aepli and Finger ([2013])). As noted in Majumder et al. ([2012]), household characteristics and income are good proxies for quality preferences. For instance, households with less income tend to choose less expensive goods within a product group. A separate regression is run for each product category i. Following Aepli and Finger ([2013]), the unit value and the proxy variables are related as follows:

where is the unit value paid by household h for item i in its region l, year y, and month m. The deviation of the household’s unit value from the median is explained by household characteristics, income, and expenditure variables, which capture the quality effect. The part of the deviation that cannot be explained by quality is captured by the error term . Furthermore, x denotes income and x2 the square of income, e is the household total expenditure for beverages, and f is the household total expenditure for food and beverages consumed away from home. Zij denotes the j th of n household characteristics, which are household size, a binary dummy variable for having children, and a dummy variable for having a university degree. Dl, Dy, and Dm are dummies for region, year, and month, respectively. To manage possible outliers more successfully, we decided to follow the suggestions in Aepli and Finger ([2013]) and to estimate the equations using a robust M-estimator using only those households that consumed the good.

To obtain regional, monthly, and yearly quality adjusted market prices we add the median unit value to the corresponding median of item i of the estimated residuals from equation (9).

The prices are then assigned to all households in the sample according to region, month, and year. Due to a low number of households consuming tea and cocoa beverages in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland in some months, we took the corresponding consumer price index for those product categories, as well as for all product categories at stage 1.

Estimation procedure and elasticity calculation

Censoring

Table 3 shows that the share of zero consumption is relatively high for all beverage product categories at stage 2. This fact has some major consequences on the estimation procedure and must be taken into account to avoid self-selection and resulting biased parameter estimates. As Deaton ([1990]) states, deleting the zero-consumption points only allows for estimating conditional effects. The most popular model for coping with censored data is the Tobit approach (Tobin [1958]; Amemiya [1984]), which is widely used for single-equation demand models. Heien and Wessels ([1990]) proposed a new approach for equation systems based on Heckman ([1979]) (for its application see e.g., Dey et al. [2011]; Lazaridis [2003]). Their approach was criticized by Shonkwiler and Yen ([1999]) and later by Vermeulen ([2001]), who showed that the revised procedure leads to inconsistent estimates. As an alternative, Shonkwiler and Yen ([1999]) proposed another frequently used approach (e.g., in Thiele [2008]; Su and Yen [2000]; Zheng and Henneberry [2011]; for wine in particular, see e.g., Stasi et al. [2011]) that is applied in this study.

In the first step, a multivariate probit is estimated (unlike Shonkwiler and Yen ([1999]), who estimated a univariate probit). We suppose that one household’s purchase of a particular beverage product category is not independent of purchase decisions for other beverage product categories due to substitution effects. The model to be estimated is:

where wi and gi are the observed dependent variables for the food product groups, and are the correspondent latent variables, gi is a binary variable representing the decision of the household to consume or not, and xij and z ' ik are explanatory variables such as income, logarithmic prices, and household characteristics. All these variables are presumed to be important determinants with respect to the decision of the household to consume or not (in this context we refer also to Thiele [2008] and Zheng and Henneberry [2011]). The error terms εi and νi are assumed to have a multivariate normal distribution, each with a mean of zero and a variance-covariance matrix V with diagonal elements of 1 and off-diagonal elements of ρrl = ρlr.

Based on the estimated parameters, we calculate the standard normal cumulative distribution function Φ( ) (cdf) and the standard normal probability density function ϕ( ) (pdf) for every household and each product category; cdf and pdf are used to correct the budget share equation (4) for a censoring of the budget share variables as follows:

Following Zheng and Henneberry ([2010]), the parameter for the pdf δi represents the covariance between the error term in the budget share equation (4) and the error term of the multivariate probit model. Equation (13) is applied only to stage 2. At stage 1, there is no need for the two-step estimation procedure due to the low level of zero consumption. We dropped the equation for expenditure on other products and services as described in Section Theoretical framework of the QUAIDS. For the two-step estimation procedure, the right hand side generally no longer adds up to one, so we estimate the full equation system following Yen et al. ([2002]) or Ecker and Qaim ([2010])d.

Despite the advantages of Shonkwiler and Yen's ([1999]) procedure, Tauchmann ([2005]) draws attention to the problem of heteroscedasticity. By expanding the budget share equation cdf and pdf, heteroscedasticity is implicitly introduced into the model (for further explanations, see Tauchmann [2005]). To avoid this problem and to estimate a heteroscedasticity robust covariance matrix, we apply the parametric bootstrap.

Expenditure endogeneity

Assuming weak separability and applying a two-stage budgeting model could lead to problems with respect to the endogeneity of the expenditure variable in the budget share equation, because the expenditure variable could be correlated with the equation errors (Attfield [1985]). To account for endogeneity, Blundell and Robin ([1999]) proposed the augmented regression technique. In a first step, we regress all the price variables, the household characteristics, and the variable for month and year of the budget share equation on the expenditure variable for every product category. On the right hand side, we further include income and its square as instruments as proposed by Bopape ([2006]). In contrast to other studies, where the equations are estimated using OLS (e.g., Fashogbon and Oni [2013]), we use a robust M-estimator to account for possible outliers. Residuals are then included in every budget share equation as additional right hand side variables. Testing the parameter of the residuals for significance allows us to check whether endogeneity is present or not.

Elasticity estimates

Income elasticities for stage 2, where censoring is an issue, are derived using the formula proposed by

which reduces to (Banks et al. [1997]) for stage 1, where μ i is the differentiation of equation (4) with respect to log m e. For the Marshallian price elasticity , we follow Zheng and Henneberry ([2010]) and calculate the full effect of a price change on demand based on the effect of the budget share equation and the effect of the multivariate probit model for stage 2:

where μ ij is the differentiation of equation (4) with respect to log p j. f τ ij is the estimated parameter for price j with respect to product category i in the multivariate probit model and δ i is defined as above. δ ij denotes the Kronecker delta, which is equal to one when i = j and otherwise is zero. For stage 1, the formula for the Marshallian price elasticity reduces to .

The Slutsky equation is applied to get the Hicksian price elasticities:

For stage 2, we first estimate conditional elasticities with respect to total expenditures on beverages. Unconditional elasticities are derived following Edgerton ([1997]). The formula for the income elasticity (unconditional) e i uc is:

where e (r)i c is the expenditure elasticity (conditional) for item i within the r th product group and e (r) uc the income elasticity for the r th product group (unconditional). The unconditional Marshallian price elasticity is calculated by:

where is the conditional Marshallian price elasticity for item i and j, w (r)j the budget share of item j within the r th product category, and ε rr M,uc the uncompensated Hicksian own-price elasticity of product category r.

The unconditional, Hicksian price elasticity is derived analogously using and the Hicksian own-price elasticity (unconditional) of product category r ε rr H,uc:

Results and discussion

Overall, the variables in the model explain between 0.47% and 0.86% of total variance at stage 1 and between 0.06% and 0.80% of total variance at stage 2. For the sake of brevity, we report the parameter estimates of stages 1 and 2, the coefficients of determination, and X2 -test statistics for the entire model in the Additional file 1: Appendix. While prices and socio-demographic variables do explain a part of the variance in consumption, the rest is determined by other factors such as lifestyle or psychographic or behavioral aspects, which are not considered further in this study (for determinants of Swiss wine demand see e.g., Brunner and Siegrist [2011]). While household size is mostly negatively correlated with budget share, the age of the households' reference person shows a positive correlation which is in line with the findings of previous studies. For the presence of young children and education, we could not show a clear relationship with respect to the budget share. The sign of the parameters varies depending on the household segment.

To verify the model specification with respect to the implementation of household characteristics and the quadratic income term, we carried out Wald-tests for every model. The test statistics reject clearly the null-hypothesis of no household characteristics for all models (Additional file 1: Appendix), which can also be derived from the estimation results for the parameter estimates in Tables 24 to 28 (in the Additional file 1: Appendix). The hypothesis that Engel curves for beverages in Switzerland are often of a nonlinear form is supported by the test results. The QUAIDS specification is therefore superior to the AIDS specification for stage 1 and stage 2, except for the models for light drinking and moderate drinking households (Additional file 1: Appendix). These findings are consistent with other findings for food demand in Switzerland (Abdulai [2002]; Aepli and Kuhlgatz [2014]). Furthermore, we tested for endogeneity of the expenditure variable in the model. The hypothesis of no endogeneity is clearly rejected for all models and confirms the importance of a correction for endogeneity (Additional file 1: Appendix), which we achieved by applying the augmented regression technique.

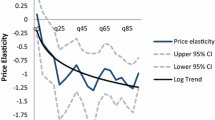

Unconditional Hicksian price and income elasticities for beverages are reported in Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 for all households and the three segments. We provide standard errors and the significance level, which are computed by the delta method discussed in Oehlert ([1992]). We provide the conditional elasticities for stage 2 in the Additional file 1: Appendix. The elasticities for stage 1 can be obtained from the author on request.

General price and income responses for beverages and for the three household segments are discussed in terms of elasticities. Due to the cross-sectional structure of the data set, elasticities should be interpreted as short-term reactions of households to price and income changes.

Income elasticities for alcoholic beverages are all positive in the model for all households. Wine is found to be a luxury good and spirits and beer are found to be necessity goods, though spirits is very closed to the luxury goods. The findings for beer are in line with previous studies (see e.g. Nelson [1997] and Selvanathan and Selvanathan [2005]). With respect to wine and spirits the findings in the literature are partially contradictory. In most studies wine and spirits are found to be luxury goods or have an elasticity which is smaller but close to one (Fogarty [2008]). Therefore our findings are in the range of variability of the results of previous studies.

Looking at the income elasticities of the three segments, alcoholic beverages are a necessity good for light drinking households, as well as for moderate drinking households, except for wine. For heavy drinking households, beer and wine are luxury goods, while spirits are necessity goodsg. Light drinking households are clearly less income-elastic for wine and beer than moderate and heavy drinking households, and heavy drinking households are much more income-elastic with respect to beer than moderate drinking households.

Almost all own-price elasticities for alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages are negative for the three household segments as well as for the model with all households. Therefore, the negativity condition is mostly fulfilled. For wine and beer, our findings show a clear decrease in the magnitude from light drinking households to heavy drinking households. Looking at the Hicksian demand elasticities, an additional 1% decrease in beer price would result in an increase of the light drinking household demand by 1.21%, while moderate drinking households would increase their consumption by 0.83% and heavy drinking households even less by 0.24%. This shows that light drinking households are relatively price elastic while heavy drinking households are inelastic. Beer is of special interest because it is the favorite beverage for young people in Switzerland. A recently study published by Dey et al. ([2013]) shows that those who practice binge drinking or other risky drinking behavior in Switzerland have a high penchant for beer. The authors (Dey et al. [2013]) suggest the relatively low price of beer in comparison to other alcoholic beverages explains these findings. The price argument likely also applies to middle-aged or older people in terms of risky drinking behavior and could be a reason why own-price elasticities for spirits, which are more expensive than beer, are almost constant between the three segments with a range from 0.83 and 0.92h. These results are in contrast to Kuo et al. ([2003]), who found that moderate drinkers show relatively higher price responses than heavy drinkers in relation to spirits.

Looking at the model for all households, non-alcoholic beverages are mostly substitutes for wine and beer. In the case of spirits, tea, cocoa beverages, and mineral water are slight complements, while coffee, non-alcoholic soft drinks, and fruit and vegetables juices are substitutes. With respect to the substitution effects between alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages among the three households segments, we did not find a clear structure. There are substitutes as well as complementary goods depending on the household segment.

The own-price elasticities for non-alcoholic beverages for the three segments are all negative except for mineral water for light drinking households and cocoa beverages for moderate drinking households. The magnitude of the Hicksian own-price elasticities shows a tendency for higher price sensitivity from light to heavy drinking households, indicating that heavy drinking households are price-sensitive to non-alcoholic beverages in contrast to alcoholic beverages.

Conclusions and policy implications

This paper reports on the income and price elasticities for different alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverage product categories with respect to light, moderate, and heavy drinking households in Switzerland. It is based on microdata of the Swiss household expenditure survey from 2000 to 2009, containing data from more than 34,000 households. We applied a two-stage quadratic almost ideal demand system, correcting for the high share of zero consumption for some product categories at stage 2 and for endogeneity of the expenditure variable. Missing price data were received by adjusting unit values for quality as recently proposed by Aepli and Finger ([2013]) and Majumder et al. ([2012]). We tested the model specification with respect to household characteristics as well as the quadratic income term, which distinguishes the QUAIDS from the AIDS. Testing for the overall significance of the household characteristics and the quadratic income terms confirms the model specification. With respect to wine and beer, moderate and heavy drinking households are less price-sensitive than light drinking households are, while for spirits we did not find a difference among the three household segments.

Our findings have major policy implications with respect to the alcohol tax. In general, the higher the negative effects of alcohol consumption and the lower the elasticity, the higher the tax should be set and vice versa. This only holds if we assume a constant elasticity function. By dividing the sample into three segments, we have shown that this does not hold for Swiss households and heavy drinking households are less price-sensitive, in particular with respect to wine and beer, than moderate or light drinking households. To fix the optimal level of a tax on alcohol, the different responses of households to price changes should be considered. As already noted by Manning et al. ([1995]), the optimal level for an alcohol tax is a trade-off between economic, public health, and social gains due to a reduction in consumption of heavy drinkers and the possible adverse social or even health effectsi on light or moderate drinkers due to the additional tax burden. Our findings clearly show that the assumption of a constant elasticity function with respect to the three defined segments is violated and that households do not respond similarly to price changes in wine and beer. A tax on those products will therefore lead to a decrease in consumption, especially in light drinking households, and to a lesser extent in moderate drinking households. The effect on heavy drinking households is minimal. From a social and health perspective, this may not be a desirable development. Therefore, before implementing a new tax on alcoholic beverages in Switzerland or in other European countries, the social and health externality costs and the economic effects of a rather small decrease in alcohol consumption among heavy drinking households must be weighed against possible adverse health or economic consequences of a sharp decline in light or moderate drinking households. To a certain extent, our findings for Switzerland can be transferred to other high-income countries and contribute to a differentiated discussion on alcohol tax.

In addition to estimating of the negative external effects of alcohol consumption, a topic for further research will be the estimation of elasticities for different household types with respect to the age of the households' reference person. As Kuo et al. ([2003]) has already noted, the price response for spirits depends on age. While younger or middle-aged people react more to price changes in spirits, older people are quite inelastic. Our findings show that households react differently to spirits than to wine and beer. Therefore, the findings of Kuo et al. ([2003]) will probably not hold for wine and beer and a further study should shed valuable light on this question.

Another point of interest is the substitution within a product category, such as shifting from more expensive alcoholic beverages to cheaper ones of lower quality due to a higher tax. Although we were not able to show this effect in our analysis, it is possible that people would buy cheaper products which are likely more risky. Gruenewald et al. ([2006]) show that consumers respond to price increases by altering their consumption, varying their brand choices as well as substituting between quality classes. This finding has consequences for a tax increase. For example, a tax increase on only high quality alcohol beverages could lead to substitution towards lower quality products and operate as a positive income effect, probably associated with higher consumption of alcoholic beverages in total (Gruenewald et al. [2006]). This possibility illustrates the need for research focused on quality substitution.

From a methodological perspective, further research should be conducted on the estimation of price and income for different household segments within a single QUAIDS by introducing cross-terms into the budget share equation, to estimate possible interaction effects between household types and price or income parameters.

Endnotes

aAfter Klonaris and Hallam ([2003]) conditional elasticities contain only direct effects on demand in comparison to unconditional elasticities, which contain direct and indirect effects. The latter are therefore more relevant in welfare analysis and for policy purposes (Klonaris and Hallam [2003]). The reason lies in multistage budgeting; a change in the price for one beverage category at the second stage within beverages (first stage) has a direct effect on the demand of all beverage categories (second stage) but has also an effect on the price index for beverages (first stage) and therefore will influence the allocation at the first stage (beverages and other commodity groups). This could have a further indirect effect on the demand for beverage categories at the second stage.

bAdult equivalent is a better proxy for the number of alcohol consuming people in a household than the number of adults because of the relatively high alcohol consumption among people 15 years old or younger in Switzerland (Annaheim and Gmel [2004]).

cShonkwiler and Yen's ([1999]) two-step estimation procedure of does not allow for the incorporation of the adding-up restriction into the model.

d

e

fA good is called a luxury good if demand increases more than proportionally as income rises (ei > 1). If demand increases less than proportionally, the good is called a necessity good (ei > 1).

gThe quality adjusted price for beer (3.00 CHF/Liter) is much lower than the price for wine (10.20 CHF/Liter) or spirits (15.18 CHF/Liter). This supports the interpretation proposed by Dey et al. ([2013]) that the low price for beer plays an important role with respect to drinking behavior.

hThe health effects depend on the assumptions made with respect to low or moderate alcohol consumption.

iThe reduction in sample size in comparison to Table 1 arises due to the deletion of households without consumption of beverages during the data collection period.

Authors' contributions

MA prepared the data, constructed the model, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript.

Additional file

References

Abdulai A: Household demand for food in Switzerland: A quadratic almost ideal demand system. Swiss J Econ Stat 2002, 138(1):1–18.

Aepli M, Finger R: Determinants of sheep and goat meat consumption in Switzerland. Agri Food Econ 2013.

Aepli M, Kuhlgatz C (2014) Meat and milk demand elasticities for Switzerland: A three stage budgeting Quadratic Almost Ideal Demand System. Submitted Aepli M, Kuhlgatz C (2014) Meat and milk demand elasticities for Switzerland: A three stage budgeting Quadratic Almost Ideal Demand System. Submitted

Akbay C, Boz I, Chern WS: Household food consumption in Turkey. Eur Review Agric Econ 2007, 34(2):209–231. 10.1093/erae/jbm011

Amemiya T: Tobit models: A survey. J Econometrics 1984, 24(1-2):3–61. 10.1016/0304-4076(84)90074-5

Angulo AM, Gil JM, Gracia A: The demand for alcoholic beverages in Spain. Agr Econ 2001, 26(1):71–83. 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2001.tb00055.x

Annaheim B, Gmel G (2004) Alkoholkonsum in der Schweiz. Scientific study, schweizerische Fachstelle für Alkohol- und andere Drogenprobleme, Lausanne. Annaheim B, Gmel G (2004) Alkoholkonsum in der Schweiz. Scientific study, schweizerische Fachstelle für Alkohol- und andere Drogenprobleme, Lausanne.

Attfield CLF: Homogeneity and endogeneity in systems of demand equations. J Econometrics 1985, 27(2):197–209. 10.1016/0304-4076(85)90087-9

Banks J, Blundell R, Lewbel A: Quadratic Engel curves and consumer demand. Rev Econ Stat 1997, 79(4):527–539. 10.1162/003465397557015

Barnett WA, Kanyama IK: Time-varying parameters in the almost ideal demand system and the Rotterdam model: Will the best specification please stand up? Appl Econ 2013, 45(29):4169–4183. 10.1080/00036846.2013.768014

Barnett WA, Seck O: Rotterdam model versus Almost Ideal Demand System: Will the best specification please stand up? J Appl Econom 2008, 23(6):795–824. 10.1002/jae.1009

Barten AP: Consumer demand functions under conditions of almost additive preferences. Econometrica 1964, 32(1-2):1–38. 10.2307/1913731

Blackorby CH, Boyce R, Russell RR: Estimation of demand systems generated by the Gorman polar form: A generalization of the S-Branch utility tree. Econometrica 1978, 46(2):345–363. 10.2307/1913905

Blundell R, Robin JM: Estimation in large and disaggregated demand systems: An estimator for conditionally linear systems. J Appl Econom 1999, 14(3):209–232. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1255(199905/06)14:3<209::AID-JAE532>3.0.CO;2-X

Bopape L (2006) The influence of demand model selection on household welfare estimates: An application to South African food expenditures. In: Dissertation. Michigan State University Bopape L (2006) The influence of demand model selection on household welfare estimates: An application to South African food expenditures. In: Dissertation. Michigan State University

Bopape L, Myers R: Analysis of household food demand in South Africa: Model selection, expenditure endogeneity, and the influence of socio-demographic effects. Paper presented at the African econometrics society annual conference, Cape Town, South Africa; 2007.

Brehe M (2007) Ein Nachfragesystem für dynamische Mikrosimulationsmodelle. In: Dissertation. University of Potsdam Brehe M (2007) Ein Nachfragesystem für dynamische Mikrosimulationsmodelle. In: Dissertation. University of Potsdam

Brunner TA, Siegrist M: A consumer-oriented segmentation study in the Swiss wine market. Brit Food J 2011, 113(3):353–373. 10.1108/00070701111116437

Cembalo L, Caracciolo F, Pomarici E: Drinking cheaply: The demand for basic wine in Italy. Aust J Agri Res Econ 2014.

Christensen LR, Jorgenson DW, Lau LJ: Transcendental logarithmic utility functions. Am Econ Rev 1975, 65(3):367–383.

Chung C, Dong D, Schmit TM, Kaiser HM, Gould BW: Estimation of price elasticities from cross-sectional data. Agribusiness 2005, 21(4):565–584. 10.1002/agr.20065

Corrao G, Rubbiati L, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Poikolainen K: Alcohol and coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Addiction 2000, 95(10):1505–1523. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951015056.x

Cox TL, Wohlgenant MK: Prices and quality effects in cross-sectional demand analysis. Am J Agr Econ 1986, 68(4):908–919. 10.2307/1242137

Cranfield JAL, Eales JS, Hertel TW, Preckel PV: Model selection when estimating and predicting consumer demands using international, cross section data. Empir Econ 2003, 28(2):353–364. 10.1007/s001810200135

De Boer P, Paap R: Testing non-nested demand relations: Linear expenditure system versus indirect addilog. Stat Neerl 2009, 63(3):368–384. 10.1111/j.1467-9574.2009.00429.x

Deaton A: Price elasticities from survey data: Extensions and Indonesian results. J Econometrics 1990, 44(3):281–309. 10.1016/0304-4076(90)90060-7

Deaton A, Muellbauer J: An Almost Ideal Demand System. Am Econ Rev 1980, 70(3):312–326.

Deaton A, Muellbauer J: Economics and consumer behavior. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1980.

Dey MM, Alam MF, Paraguas FJ: A multistage budgeting approach to the analysis of demand for fish: An application to inland areas of Bangladesh. Mar Res Econ 2011, 26(1):35–58. 10.5950/0738-1360-26.1.35

Dey M, Gmel G, Studer J, Dermota P, Mohler-Kuo M: Beverage preferences and associated drinking patterns, consequences and other substance use behaviours. Eur J Public Health 2013.

Doran CM, Byrnes JM, Cobiac LJ, Vandenberg B, Vos T: Estimated impacts of alternative Australian alcohol taxation structure on consumption, public health and government revenues. Med J Aust 2013, 199(9):619–622. 10.5694/mja13.10605

Ecker O, Qaim M: Analyzing nutritional impacts of policies: An empirical study for Malawi. World Dev 2010, 39(3):412–428. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.08.002

Edgerton DL: Weak separability and the estimation of elasticities in multistage demand systems. Am J Agr Econ 1997, 79(1):62–79. 10.2307/1243943

Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas M-I, Corella D, Arós F, Gómez-Gracia E, Ruiz-Gutiérrez V, Fiol M, Lapetra J, Lamuela-Raventos Serra-Majem L, Pintó X, Basora J, Muñoz MA, Sorlí JV, Martínez JA, Martínez-González MA: Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. New England J Med 2014.

Statistiken zur Nahrungsmittelkette - Vom Erzeuger zum Verbraucher. Press release, EU Commission, Brussels; 2013.

Fashogbon AE, Oni OA: Heterogeneity in rural household food demand and its determinants in Ondo State, Nigeria: An application of quadratic almost ideal demand system. J Agric Sci 2013, 5(2):169–177.

Alkohol in der Schweiz - Übersicht. Swiss Federal Department of Finance, Bern; 2009.

Fergusson SM, McLeod GG, Horwood JL: Alcohol misuse and psychosocial outcomes in young adulthood: Results from a longitudinal birth cohort studied to age 30. Drug Alcohol Depen 2013, 133(2):513–519. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.015

Fogarty J: The demand for beer, wine and spirits: Insights from a meat analysis approach. 2008.

Faktenblatt: Entwicklung des Alkoholkonsum der Schweiz seit den 1880er Jahren. Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, Bern; 2013.

Alcohol policy regulation in Europe. Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, Bern; 2014a.

Swiss food composition database. Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, Bern; 2014b.

Gallet CA: The demand for alcohol: A meta-analysis of elasticities. Aust J Agr Resour Ec 2007, 51(2):121–135. 10.1111/j.1467-8489.2007.00365.x

Gallet CA: The income elasticity of meat: a meta-analysis. Aust J Agr Resour Ec 2010, 54(4):477–490. 10.1111/j.1467-8489.2010.00505.x

Gruenewald PJ, Ponicki WR, Holder HD, Romelsjö A: Alcohol prices, beverage quality, and the demand for alcohol: Quality substitutions and price elasticities. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006, 30(1):96–105. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00011.x

Hagenaars AJM, De Vos K, Zaidi MA: Poverty statistics in the late 1980s: Research based on micro-data. Office for Official Publications of the European Community, Luxembourg; 1994.

Heckman J: Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 1979, 47(1):153–161. 10.2307/1912352

Heeb JL, Gmel G, Zurbrügg CH, Kuo M, Rehm J: Changes in alcohol consumption following a reduction in the price of spirits: a natural experiment in Switzerland. Addiction 2003, 98(10):1433–1446. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00461.x

Heien D, Wessels CR: Demand systems estimation with microdata: A censored regression approach. J Bus Econ Stat 1990, 8(3):365–371.

Holt MT, Goodwin BK: The almost ideal and translog demand systems. 2009.

Jacobs L, Steyn N: Commentary: If you drink alcohol, drink sensibly: Is this guideline still appropriate? Ethn Dis 2013, 23(1):110–115.

Jithitikulchai T: U.S. alcohol consumption: Tax instrumental variables in Quadratic Almost Ideal Demand System. 2011.

Klonaris S, Hallam D: Conditional and unconditional food demand elasticities in a dynamic multistage demand system. Appl Econ 2003, 35(5):503–514. 10.1080/00036840210148058

Kuo M, Heeb JL, Gmel G, Rehm J: Does price matter? The effect of decreased price on spirits consumption in Switzerland. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003, 27(4):720–725. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2003.tb04410.x

Lazaridis P: Household meat demand in Greece: A demand systems approach using microdata. Agribusiness 2003, 19(1):43–59. 10.1002/agr.10044

Lewbel A, Pendakur K: Tricks with Hicks: The EASI demand system. Am Econ Rev 2009, 99(3):827–863. 10.1257/aer.99.3.827

Majumder A, Ray R, Sinha K: Calculating rural-urban food price differentials from unit values in household expenditure surveys: A comparison with existing methods and a new procedure. Am J Agr Econ 2012, 94(5):1218–1235. 10.1093/ajae/aas064

Manning WG, Blumberg L, Moulton LH: The demand for alcohol: The differential response to price. J Health Econ 1995, 14(2):123–148. 10.1016/0167-6296(94)00042-3

McKelvey C: Price, unit value, and quality demanded. J Dev Econ 2011, 95(2):157–169. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.05.004

Mhurchu CN, Eyles H, Schilling C, Yang Q, Kaye-Blakem W, Genç M, Blakely T: Food prices and consumer demand: Differences across income levels and ethnic groups. PLoS One 2013.

Moschini G, Moro D, Green RD: Maintaining and testing separability in demand systems. Am J Agr Econ 1994, 76(1):61–73. 10.2307/1243921

Nelson JP: Economic and demographic factors in US alcohol demand: A growth-accounting analysis. Empir Econ 1997, 22(1):83–102. 10.1007/BF01188171

Oehlert GW: A note on the delta method. Am Stat 1992, 46(1):27–29.

Perali F, Chavas JP: Estimation of censored demand equations from large cross-section data. Am J Agr Econ 2000, 82(4):1022–1037. 10.1111/0002-9092.00100

Pollak RA, Wales TJ: Estimation of complete demand systems from household budget data: The linear and quadratic expenditure systems. Am Econ Rev 1978, 68(3):348–359.

Reavley NJ, Jorm AF, McCann TV, Lubman DI: Alcohol consumption in tertiary education students. BMC Public Health 2011.

Rehn N, Room R, Edwards G: Alcohol in the European region: Consumption, harm and policies, Report. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen; 2001.

Rice N, Carr-Hill R, Dixon P, Sutton M: The influence of households on drinking behavior: A multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med 1998, 46(8):971–979. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)10017-X

Zahlen und Fakten - Konsum. Swiss Alcohol Board, Bern; 2013.

Sabia S, Elbaz A, Britton A, Bell S, Dugravot A, Shipley M, Kivimaki M, Sing-Manoux A: Alcohol consumption and cognitive decline in early old age. Neurology 2014.

Sacks JJ, Roeber J, Bouchery EE, Gonzales K, Chaloupka FJ, Brewer RD: State costs of excessive alcohol consumption, 2006. Am J Prev Med 2013, 45(4):474–485. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.004

Schwartz LM, Persson EC, Weinstein SJ, Graubard BI, Freedman ND, Mannisto S, Albanes D, McGlynn KA: Alcohol consumption, one-carbon metabolites, liver cancer and liver disease mortality. PLoS One 2013, 8(10):e78156. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078156

Selvanathan S, Selvanathan EA: The demand for alcohol, tobacco and marijuana: International evidence. Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot; 2005.

Haushaltsbudgeterhebung 2005. Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Neuchâtel; 2011.

Shonkwiler JS, Yen ST: Two-step estimation of a censored system of equations. Am J Agr Econ 1999, 81(4):972–982. 10.2307/1244339

Stasi A, Seccia A, Nardone G: Market power and price competition in the Italian wine market. Enometrica, Review of the Vineyard Data Quantification Society (VDQS) and the European Association of Wine Economists (EuAWE) - Macerata University 2010.

Stasi A, Seccia A, Nardone G: Italian wine consumers' preferences and impact of taxation on wines of different quality and source. 2011.

Su SJ, Yen S: A censored system of cigarette and alcohol consumption. J Appl Econ 2000, 32(6):729–737. 10.1080/000368400322354

Tafere K, Taffesse AS, Tamru S: Food demand elasticities in Ethiopia: Estimates using household income consumption expenditure (HICE) survey data. In ESSP II Working Paper 11. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington; 2010.

Tauchmann H: Efficiency of two-step estimators for censored systems of equations: Shonkwiler and Yen reconsidered. J Appl Econ 2005, 37(4):367–374. 10.1080/0003684042000306987

Theil H: The Information approach to demand analysis. Econometrica 1965, 33(1):67–87. 10.2307/1911889

Thiele S: Elastizitäten der Nachfrage privater Haushalte nach Nahrungsmitteln - Schätzung eines AIDS auf Basis der Einkommens- und Verbrauchsstichprobe 2003. Agrarwirtschaft 2008, 57(5):258–268.

Thiele S: Erhöhung der Mehrwertsteuer für Lebensmittel: Budget- und Wohlfahrtseffekte für Konsumenten. Jahrb Natl Stat 2010, 230(1):115–130.

Tobin J: Estimation of relationships for limited dependent variables. Econometrica 1958, 26(1):24–36. 10.2307/1907382

Van Oers JAM, Bongers IMB, Van de Goor LAM, Garretsen HFL: Alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, problem drinking, and socioeconomic status. Alcohol Alcoholism 1999, 34(1):78–88. 10.1093/alcalc/34.1.78

Vermeulen F: A note of Heckman-type corrections in models for zero expenditures. Appl Econ 2001, 33(9):1089–1092. 10.1080/00036840010004004

Wakabayashi I: Relationship between alcohol intake and lipid accumulation product in middle-aged men. Alcohol Alcoholism 2013, 48(5):535–542. 10.1093/alcalc/agt032

Prevention of cardiovascular disease. Report. World Health Organization, Geneva; 2007.

Xuan ZM, Nelson TF, Heeren T, Blanchette J, Nelson DE, Gruenewald P, Naimi TS: Tax policy, adult binge drinking, and youth alcohol consumption in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2013, 37(10):1713–1719.

Yen ST, Kan K, Su SJ: Household demand for fats and oils: Two-step estimation of a censored demand system. Appl Econ 2002, 34(14):1799–1806. 10.1080/00036840210125008

Zheng Z, Henneberry SR: An analysis of food grain consumption in urban Jiangsu province of China. J Agri Appl Econ 2010, 42(2):337–355.

Zheng Z, Henneberry SR: Household food demand by income category: Evidence from household survey data in an urban Chinese province. Agribusiness 2011, 27(1):99–113. 10.1002/agr.20243

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted with support from the Swiss Federal Office for Agriculture within the project "Food demand analysis in Switzerland".

We thank Robert Finger, University of Bonn, for his helpful comments on a previous version.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

40100_2014_15_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Appendix. Table S1.: Wald tests for household characteristics. Table S2. Wald tests for the quadratic term in the QUAIDS. Table S3. Wald tests for endogeneity of the expenditure variable. Table S4. Conditional, Marshallian price and income elasticities at stage 2, all households (at sample means). Table S5. Conditional, Hicksian price and income elasticities at stage 2, all households (at sample means). Table S6. Conditional, Marshallian price and income elasticities at stage 2, light drinking household (at sample means). Table S7. Conditional, Hicksian price and income elasticities at stage 2, light drinking household (at sample means). Table S8. Conditional, Marshallian price and income elasticities at stage 2, moderate drinking household (at sample means). Table S9. Conditional, Hicksian price and income elasticities at stage 2, moderate drinking household (at sample means). Table S10. Conditional, Marshallian price and income elasticities at stage 2, heavy drinking household (at sample means). Table S11. Conditional, Hicksian price and income elasticities at stage 2, heavy drinking household (at sample means). Table S12. Parameter estimates of the budget share equation, Stage 1. Table S13. Parameter estimates of the budget share equation, Stage 2, all households. Table S14. Parameter estimates of the budget share equation, Stage 2, light drinking household. Table S15. Parameter estimates of the budget share equation, Stage 2, moderate drinking households. Table S16. Parameter estimates of the budget share equation, Stage 2, heavy drinking households. (DOCX 92 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aepli, M. Consumer demand for alcoholic beverages in Switzerland: a two-stage quadratic almost ideal demand system for low, moderate, and heavy drinking households. Agric Econ 2, 15 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-014-0015-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-014-0015-0