Abstract

Background

The prevalence of infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-E. coli) is increasing worldwide, but the setting in which this increase is occurring is not well defined. We compared trends and risk factors for ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria in community vs healthcare settings.

Methods

We collected electronic health record data on all patients with E. coli isolated from urine cultures in a safety-net public healthcare system from January 2014 to March 2020. All analyses were stratified by healthcare-onset/associated (bacteriuria diagnosed > 48 h after hospital admission or in an individual hospitalized in the past 90 days or in a skilled nursing facility resident, N = 1277) or community-onset bacteriuria (bacteriuria diagnosed < 48 h after hospital admission or in an individual seen in outpatient clinical settings without a hospitalization in the past 90 days, N = 7751). We estimated marginal trends from logistic regressions to evaluate annual change in prevalence of ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria among all bacteriuria. We evaluated risk factors using logistic regression models.

Results

ESBL-E. coli prevalence increased in both community-onset (0.91% per year, 95% CI 0.56%, 1.26%) and healthcare-onset/associated (2.31% per year, CI 1.01%, 3.62%) bacteriuria. In multivariate analyses, age > 65 (RR 1.88, CI 1.17, 3.05), male gender (RR 2.12, CI 1.65, 2.73), and Latinx race/ethnicity (RR 1.52, CI 0.99, 2.33) were associated with community-onset ESBL-E. coli. Only male gender (RR 1.53, CI 1.03, 2.26) was associated with healthcare-onset/associated ESBL-E. coli.

Conclusions

ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria frequency increased at a faster rate in healthcare-associated settings than in the community between 2014 and 2020. Male gender was associated with ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria in both settings, but additional risks—age > 65 and Latinx race/ethnicity—were observed only in the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keypoints

The frequency of bacteriuria caused by Escherichia coli producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) increased from 2014 to 2020 in community and healthcare settings among patients diagnosed at a public healthcare system. Risk factors differed between community-onset versus healthcare-onset/associated ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria.

Introduction

Infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae are a growing public health threat [1, 2]. In 2019, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) designated ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae as”serious threat” pathogens [2]. While the first US cases of infections caused by ESBL-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-E. coli) were identified in a skilled nursing facility, it is now a nascent concern in community settings [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Recent hospitalization and prior antibiotic use are major drivers of ESBL-E. coli infections, but factors unrelated to healthcare are increasingly recognized, including international travel and consumption of meat contaminated with ESBL-E. coli.[9,10,11,12,13,14] However, most studies compare infection with ESBL-E. coli to infection with drug-susceptible E. coli to assess risk for ESBL-E. coli infections [11]. As such, identified risks may determine infection with antimicrobial resistant E. coli and not necessarily ESBL-E. coli. Furthermore, despite the increasing prevalence of community-onset ESBL-E. coli infections, little is known about risk factors for such infections in community settings.

Previously, we found increasing trends in ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria in the San Francisco safety-net public healthcare system from 2012 to 2018, but community-onset cases could not be differentiated from those associated with healthcare exposure [15]. Here, we compared community-onset vs healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria episodes caused by ESBL-E. coli in the same public healthcare system from 2014 to 2020. This healthcare system serves a multiethnic, low-income, under-studied population residing in various neighborhoods. Identifying risk factors specific to community-onset bacteriuria caused by ESBL-E. coli in this population is paramount to devising effective antibiotic stewardship efforts and targeted interventions to reduce transmission within communities.

Methods

Study design and settings

This is an observational study drawn from electronic medical record (eMR) data at the San Francisco public healthcare system for all patients whose urine culture grew E. coli from January 2014 to March 2020. This healthcare system includes 15 primary care outpatient clinics as part of the San Francisco Health Network (SFHN), the San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH), an acute care hospital, and Laguna Honda Hospital (LHH), a skilled nursing facility. SFHN patients and LHH residents are usually hospitalized at SFGH. The SFGH microbiology laboratory processes all laboratory tests for this public healthcare system. Data on all urine cultures were collected, including bacterial species and antimicrobial susceptibility test results. We analyzed bacteriuria episodes, which may represent either urinary tract infection or asymptomatic bacteriuria, caused by E. coli. Bacteriuria episodes were defined as a single urine culture growing E. coli. If multiple cultures were sent on the same day, only one culture was considered. E. coli-positive urine cultures from separate days were considered to be separate episodes, as we could not differentiate between an untreated and a repeat urinary tract infection.

Exposure and outcome measures

To evaluate prevalence trends, we defined culture date as years since baseline (January 2014). Our primary independent variables were extracted from eMRs: age at time of culture (0–17, 18–34, 35–64, or over 65 years); gender (male or female); race/ethnicity (Asian, Black, Latinx, White, or Other); and preferred language (any Chinese dialect, English, Spanish, or Other).

Healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria episodes were defined as cases in which a urine culture, obtained from a) inpatients after at least 48 h of hospital admission, b) outpatients who had been hospitalized in the 90 days prior to culture, or c) residents of the skilled nursing facility, grew E. coli. Community-onset E. coli bacteriuria episodes were defined as cases in which a urine culture, obtained in a) an outpatient clinic or emergency department setting, or b) within 48 h of inpatient admission, grew E. coli. These simplified definitions for healthcare onset/associated and community-onset were created due to the small sample size of community-onset healthcare-associated bacteriuria episodes. We sought to identify factors associated with antimicrobial resistance in community-onset bacteriuria other than prior hospitalization, which is an already well-studied risk factor for antimicrobial resistance. Here, we assumed that individuals who had been hospitalized in the 90 days prior to urine culture would have similar healthcare exposures to those individuals whose urine cultures were obtained after 48 h of hospitalization.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST)

The microbiology laboratory performs AST with Microscan and disk diffusion tests, with reports of resistance based on CLSI breakpoint standards [16]. The microbiology laboratory reports extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing E. coli (ESBL-E. coli) as an E. coli strain resistant to ceftazidime or cefotaxime and inhibited by clavulanic acid using broth microdilution, per 2016 CLSI guidelines [16]. Results reported as “intermediate resistance” were considered resistant in this study (“Appendix”).

Bacteriuria episode caused by ESBL-E. coli was the main outcome of interest. Sub-analyses included E. coli with resistance to nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin (most commonly used to treat urinary tract infections), any resistance (defined as resistance to any antibiotic class based on all antibiotics tested routinely in the microbiology laboratory, see “Appendix” for a complete list), and multidrug resistance (defined as resistance to 3 or more classes of antibiotics). Sub-analyses initially included resistance to aminoglycosides and carbapenems; Additional file 1: Table S7 reports percentage resistance per year for each bacteriuria type and place of care.

Statistical data analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical data and mean values with standard deviations for continuous data, were used to summarize key exposure and outcome variables. Differences in overall frequency of ESBL-E. coli and patient characteristics for community-onset versus healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria were evaluated with chi-squared tests and t-tests. Annual changes in resistance to antimicrobial agents from 2014 to 2020 were fit with logistic regression models and trends were estimated based on marginal effects, separately for community-onset and for healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria. To assess changes in the overall patient population, annual change in racial/ethnic distribution of patients with E. coli bacteriuria were also fit with logistic regression models and trends were estimated based on marginal effects. Unadjusted and covariate adjusted logistic regression models were performed separately for community-onset bacteriuria and healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria to assess which demographic characteristics of patients with bacteriuria predicted E. coli resistant to antimicrobial agents (considering as separate outcomes: ESBL-E. coli; resistance to each of 3 antibiotics separately [nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin]; any drug resistance; and multidrug resistance). Bootstrap (clustered at the individual level) confidence intervals were reported for adjusted logistic regressions to adjust for repeated measures on unique patients [17]. All analyses were conducted by RStudio4 version 1.3.1073. We report 95% confidence intervals to characterize uncertainty in our effect estimates. Sub-analyses were also performed separately for place of care: outpatient, inpatient, and skilled nursing facility.

Results

Characteristics of the study samples and patients

From January 2014 to March 2020, 82,800 urine samples were processed at the SFGH clinical microbiology laboratory. Of these, 13,522 urine cultures grew an identifiable organism, of which 9028 (67%) grew E. coli (7751 community-onset and 1277 healthcare-onset/associated). Of the 9028 urine cultures, 224 (2%) were obtained from catheterizations and 8804 (98%) from clean catch urine collections.

We identified 6291 unique patients with an E. coli bacteriuria episode. There were 5576 patients who met the definition of a community-onset E. coli bacteriuria. In addition, 926 patients had a healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria; given that a patient may have had multiple bacteriuria episodes, these were not mutually exclusive (Table 1). There were 4844 outpatients, 1183 inpatients, and 264 skilled nursing facility residents. Fifteen hundred patients had more than one E. coli bacteriuria episode; one patient had as many as 27 episodes. Patients with community-onset bacteriuria (mean age 46) were younger compared to patients with healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria (mean age 60). Patients with bacteriuria were predominantly women (85%). The study population was multiethnic, with 40% Latinx, 20% Asian, 18% White, and 14% Black patients. Demographic characteristics of outpatients, inpatients and skilled nursing facility residents can be found in Supplemental Table 1. We conducted analyses to assess change in percent race/ethnicity distribution in patients with E. coli bacteriuria from 2014 to 2020. We found that percent annual change in Latinx patients with E. coli bacteriuria increased by 1.44% (95% CI 0.78, 2.10), whereas percent change in Black patients (− 0.5%; 95% CI − 0.99, − 0.04) and patients identified as other (− 0.76%; 95% CI − 1.12, − 0.41) decreased annually. Annual percent change in other race/ethnic groups were not significant (data not shown).

Prevalence of antimicrobial resistant E. coli

Table 2 shows the overall frequency at which the E. coli bacteriuria episodes were resistant to antimicrobial agents. ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria frequency was higher in healthcare onset/associated bacteriuria episodes (24%) compared to those of community-onset bacteriuria (8%) (P < 0.001) (Tables 2 and 3). ESBL-E. coli accounted for only 13% of community-onset but 34% of healthcare onset/associated antimicrobial resistant E. coli bacteriuria episodes (P < 0.001). Bacteriuria episodes caused by ESBL-E. coli had 4.14 (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.41, 5.02) times the risk of nitrofurantoin resistance, 3.89 (95% CI 3.41, 4.43) times the risk of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance, and 12.95 (95% CI 11.15, 15.05) times the risk of ciprofloxacin resistance compared to bacteriuria caused by non-ESBL-E. coli. Amongst 14 carbapenem-resistant E. coli bacteriuria episodes, 6 were identified as community-onset, of which 2 were caused by non-ESBL-E. coli. All eight carbapenem-resistant E. coli strains causing healthcare onset/associated bacteriuria were ESBL-E. coli. The majority of ESBL-E. coli isolates were multidrug resistant (72% of 931) but only a minority (39% of 1707 isolates) of multidrug resistant episodes were due to ESBL-E. coli.

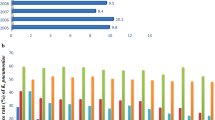

Trend over time of bacteriuria episodes caused by drug-resistant E. coli

ESBL-E. coli frequency in community-onset bacteriuria episodes increased from 6% in 2014 to 10% in 2020 (although 2020 included only 3 months of data), ranging from 5 to 10% and increasing an average of 0.91% (95% CI 0.56%, 1.26%) per year (Table 4 and Fig. 1). ESBL-E. coli frequency in healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria episodes increased from 17% in 2014 to 24% in 2020, ranging from 17 to 29% and increasing an average of 2.31% (95% CI 1.01%, 3.62%) per year. ESBL-E. coli frequency increased an average of 1.03% (95% CI 0.67, 1.40) per year in outpatients and an average of 3.51% (95% CI 1.50, 5.52) per year in skilled nursing facility residents; it did not increase significantly in inpatients (Additional file 1: Table S2). Nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance and resistance to any antimicrobial agent also increased (Table 4 and Fig. 1).

Temporal trend in community-onset vs healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria caused by antimicrobial resistant E. coli by semester, 2014–2020. Note: bar = number of bacteriuria episodes, line = percent resistance. a ESBL-producing. 1. Community-onset. 2. Healthcare-onset/associated. b Nitrofurantoin. 1. Community-onset. 2. Healthcare-onset/associated. c Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. 1. Community-onset. 2. Healthcare-onset/associated. d Ciprofloxacin. 1. Community-onset. 2. Healthcare-onset/associated. e Any resistance. 1. Community-onset. 2. Healthcare-onset/associated. f Multidrug resistance. 1. Community-onset. 2. Healthcare-onset/associated

Association between patient demographic characteristics and ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria by community-onset and healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria

In univariate logistic regression models, among all E. coli bacteriuria episodes, community-onset ESBL-E. coli was associated with age over 65 years (risk ratio [RR] 1.93, 95% CI 1.26, 2.94), male gender (RR 2.24, CI 1.87, 2.69), and Chinese dialect (RR 1.37, CI 1.03, 1.81) or Spanish (RR 1.25, CI 1.05, 1.48) as a preferred language (Table 5). In models comparing ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria episodes to episodes caused by drug-resistant E. coli, older age, being male, and Chinese dialect as a preferred language, but not Spanish, were significantly associated.

In multivariate logistic regression models adjusted for age category, gender, race/ethnicity and preferred language, community-onset ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria was associated with age older than 65 years (RR 1.88, CI 1.17, 3.05) and male gender (RR 2.12, CI 1.65, 2.73), among all E. coli bacteriuria episodes (Table 6). Among bacteriuria episodes caused by drug-resistant E. coli, ESBL- E. coli bacteriuria was associated with male gender (RR 1.90, CI 1.50, 2.41) as well as age older 65 years (RR 1.60, CI 0.98, 2.61) although the CI included the null. Association of ESBL- E. coli bacteriuria with Latinx race/ethnicity was also observed although the CI included the null among all E. coli bacteriuria episodes (RR 1.52, CI 0.99, 2.33) and among bacteriuria episodes caused by drug-resistant E. coli (RR 1.39, CI 0.98, 1.98).

For healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria episodes, among all E. coli bacteriuria episodes, ESBL-E. coli was associated only with male gender in both univariate (RR 1.61, CI 1.29, 2.02) and multivariate (RR 1.53, CI 1.03, 2.26) analyses. Among episodes caused by drug-resistant E. coli, ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria was associated with male gender only in univariate analyses (RR 1.44, CI 1.50, 1.81).

The results of analysis of association between patient demographic characteristics and other antimicrobial agents are described Supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

Association between patient demographic characteristics and ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria episodes by place of care

In multivariate regression models adjusted for age category, gender, race/ethnicity, preferred language, and hospitalization in the 90 days prior to urine culture, among all E. coli bacteriuria episodes from inpatients, male gender (RR 1.66, CI 1.13, 2.43) and hospitalization in the 90 days prior to urine culture (RR 2.35, CI 1.72, 3.20) were significantly associated with ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria (Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6). Among bacteriuria episodes caused by drug-resistant E. coli in inpatients, male gender (RR 1.38, CI 0.98, 1.93), although the CI included the null, and hospitalization in the 90 days prior to urine culture (RR 1.97, CI 1.51, 2.57) were ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria.

For outpatients, in multivariate regression models, among all E. coli bacteriuria episodes, significant predictors of ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria were age older than 65 years (RR 1.62, CI 1.00, 2.62), male gender (RR 2.00, CI 1.52, 2.64), Latinx race/ethnicity (RR 1.65, CI 1.04, 2.62), and hospitalization in the 90 days before culture (RR 2.81, CI 2.04, 3.88). Among episodes caused by drug-resistant E. coli, ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria was associated with male gender and hospitalization in the 90 days before culture; association with Latinx race/ethnicity was noted, although the CI included the null (RR 1.47, CI 0.98, 2.22). No associations were found among skilled nursing facility residents (Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6).

Results of associations between patient demographic characteristics and other antimicrobial agents are described in Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6.

Discussion

In this study of drug-resistant E. coli bacteriuria spanning more than 6 years in a safety-net public healthcare system serving a diverse population, we found antimicrobial resistant E. coli frequency to increase over time in both community and healthcare settings. The magnitude of the increase was greatest among ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria, which doubled in community settings and increased by more than 40% in healthcare settings. Older age, male sex, and Chinese dialect or Spanish as a preferred language (or, in some models, Latinx race/ethnicity) were associated with higher prevalence of ESBL-E. coli among all E. coli bacteriuria episodes.

Increasing prevalence of ESBL-E. coli in community-onset and healthcare onset/associated infections is now observed worldwide [4, 10, 12, 18,19,20,21,22]. A 2019 CDC report showed a 50% increase in hospital- and community-onset infections caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae between 2012 and 2017 in the US [2]. A report from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART) found prevalence of urinary tract infections caused by ESBL-E. coli to increase from 7.8 to 18.3% between 2010 and 2014 in the US, particularly among hospital-associated infections [23]. In contrast, the authors found increasing prevalence in community-onset infections in Canada [23]. Most recently, a report on urinary tract infections in US hospitalized patients found a prevalence of 17.2% for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae [24]. We have previously shown increase in ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria cases in the same San Francisco public healthcare system, but were unable to decipher whether this increase occurred in community or healthcare settings [15]. Here, while prevalence and increase per year was greater in healthcare onset/associated ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria, especially in skilled nursing facility residents as shown in separate analyses, we also found a significant increase among community-onset bacteriuria.

We first compared ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria to bacteriuria caused by all other E. coli strains (non-ESBL drug-resistant and drug-susceptible E. coli), which would not necessarily distinguish risk factors associated with ESBL-E. coli from those associated with drug-resistant E. coli. Therefore, we performed secondary analyses comparing ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria to bacteriuria caused by non-ESBL drug-resistant E. coli. For community-onset ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria, we found older age and male gender to be associated risk factors. For healthcare-onset/associated bacteriuria, we found male gender to be associated with ESBL-E. coli.

The association with older age and male gender may represent complicated urinary tract infections more likely to occur in these populations, which may include catheter-associated infections or prostatitis requiring prolonged treatment with extended-spectrum beta-lactam drugs [25]. Since multidrug resistance is associated with ESBL-E. coli, factors contributing to frequent antibiotic exposures among older persons in community settings, such as frequent contact with healthcare, higher likelihood of recurrent urinary tract infection, and urinary retention requiring catheterization, may also contribute to the ESBL-E. coli selection [9, 11, 26,27,28].

Few studies have found differences in ESBL-E. coli infection by race/ethnicity, independent of healthcare exposures. A New York study found that children identified as Asian had greater odds of infection with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae [13]. Studies utilizing genotyping methods have found that the majority of community-onset urinary tract infection caused by ESBL-E. coli are caused by major pandemic E. coli lineages belonging to specific sequence types, including ST131 and ST69 [9, 10, 29]. This may point to common-source exposures in the community. There is mounting evidence that infection with ESBL-E. coli is associated with international travel, particularly to South Asian countries, and food habits, including eating meat contaminated with ESBL-E. coli [11,12,13,14].

No study to our knowledge has found higher risk of ESBL-E. coli in Latinx populations. Our findings may represent increased access to antibiotics by this population in San Francisco, but prior studies from other regions in the US found no difference in access to and use of non-prescribed antibiotics among Latinx compared to non-Latinx individuals [30]. A majority of Latinx patients in this public healthcare system come from Mexico. Travel to Mexico may be a risk factor in our study population. A report from the SMART study showed that Mexico has the highest prevalence of community infections caused by ESBL-E. coli in Latin America [31]. Thus, unmeasured risk factors, such as travel and food consumption, may also be driving increasing community-onset bacteriuria caused by ESBL-E. coli. Additionally, we found that representation of Latinx patients in those with E. coli bacteriuria increased annually. While Covered California was founded in 2012, Healthy San Francisco, a program designed to provide healthcare services for uninsured San Francisco residents which works directly with our healthcare system, started in 2007. It is less likely that the increase in Latinx patients with E. coli bacteriuria is due to increased healthcare coverage, but perhaps to a change in use of healthcare services. The temporal increase and association of ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria among Latinx patients we observed in this study may have been driven by the temporal increase in this population group at risk.

While co-resistance of ESBL-E. coli to other antimicrobial agents, specifically fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, is very common [3, 9, 32,33,34], even more concerning is our finding of phenotypic carbapenem co-resistance amongst ESBL-E. coli. We found that 12 (86%) of 14 carbapenem-resistant E. coli were ESBL-E. coli, although we do not have genetic information to evaluate whether they were carbapenemase-producers. A new report from the CRACKLE2 study found that 20% of non-carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriales isolated from hospitalized patients produced CTX-M, a common ESBL type [35]. Additionally, prior studies have found ESBL-E. coli co-resistance to nitrofurantoin to be either absent or negligible [36, 37]. Our finding that ESBL-E. coli co-resistance to nitrofurantoin was higher than that of co-resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole may be representative of local antimicrobial resistance patterns, possibly driven by predominant E. coli sequence types.

There are several limitations to our study. First, community-onset cases were defined as cases with no history of hospitalizations in the 90 days at SFGH or LHH prior to urine culture. We did not obtain patient information before 90 days, when such patients could have had other healthcare exposures. Second, it may be that we underestimated hospitalization in the 90 days prior to urine culture if individuals were hospitalized in other healthcare systems. Prior studies, however, have shown high retention rate of patients within our public healthcare system [38]. Third, we combined community-onset healthcare-associated bacteriuria episodes with healthcare-onset ones. This is a simplified definition of healthcare-associated infections. Fourth, this is a retrospective study based on electronic health records, and thus we were not able to conduct molecular characterization of E. coli isolates. Lastly, while our study population is diverse in its racial/ethnic representation and their San Francisco neighborhoods, it is homogenous in that individuals receiving care in this public healthcare system have similar socio-economic circumstances. Thus, findings from our study may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusion

Our findings raise concerning trends in both community and healthcare settings of ESBL-E. coli bacteriuria among patients examined at a San Francisco safety-net public health system. As bacteriuria, in particular urinary tract infections, often precede complications such as bacteremia and sepsis, this observation has serious implications for the clinical management of many types of infections. These findings also have important public health implications, emphasizing an increasing need for better surveillance and antibiotic stewardship programs for community-onset infections.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ten threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019.

Kassakian SZ, Mermel LA. Changing epidemiology of infections due to extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing bacteria. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3(1):9.

van Driel AA, Notermans DW, Meima A, Mulder M, Donker GA, Stobberingh EE, Verbon A. Antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli isolated from uncomplicated UTI in general practice patients over a 10-year period. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:2151.

Pitout JD, Laupland KB. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(3):159–66.

Bours PH, Polak R, Hoepelman AI, Delgado E, Jarquin A, Matute AJ. Increasing resistance in community-acquired urinary tract infections in Latin America, five years after the implementation of national therapeutic guidelines. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(9):e770-774.

Lagunas-Rangel FA. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of bacteria causing urinary tract infections in Mexico: single-centre experience with 10 years of results. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;14:90–4.

Park JJ, Seo YB, Lee J. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Enterobacteriaceae in community-acquired urinary tract infections during a 5-year period: A Single Hospital Study in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2017;49(3):184–93.

Doi Y, Park YS, Rivera JI, Adams-Haduch JM, Hingwe A, Sordillo EM, Lewis JS 2nd, Howard WJ, Johnson LE, Polsky B, et al. Community-associated extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(5):641–8.

de Souza da-Silva AP, de Sousa VS, de Araújo Longo LG, Caldera S, Baltazar ICL, Bonelli RR, Santoro-Lopes G, Riley LW, Moreira BM: Prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant and broad-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant community-acquired urinary tract infections in Rio de Janeiro: Impact of genotypes ST69 and ST131. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;85:104452.

Butcher CR, Rubin J, Mussio K, Riley LW. Risk factors associated with community-acquired urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum ≤-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: a Systematic review. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2019;6:300–9.

Søraas A, Sundsfjord A, Sandven I, Brunborg C, Jenum PA. Risk factors for community-acquired urinary tract infections caused by ESBL-producing enterobacteriaceae-a case-control study in a low prevalence country. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e69581.

Strysko JP, Mony V, Cleveland J, Siddiqui H, Homel P, Gagliardo C. International travel is a risk factor for extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae acquisition in children: a case-case-control study in an urban U. S. Hospital. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14(6):568–71.

Ukah UV, Glass M, Avery B, Daignault D, Mulvey MR, Reid-Smith RJ, Parmley EJ, Portt A, Boerlin P, Manges AR. Risk factors for acquisition of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli and development of community-acquired urinary tract infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(1):46–57.

Raphael E, Chambers HF. Differential trends in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infections in four health care facilities in a single metropolitan area: a retrospective analysis. Microb Drug Resist. 2020;27:154.

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 26th ed. CLSI supplement M100S. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2016.

Esarey J, Menger A. Practical and effective approaches to dealing with clustered data. Polit Sci Res Methods. 2018;7(3):541–59.

Kim YH, Yang EM, Kim CJ. Urinary tract infection caused by community-acquired extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing bacteria in infants. Jornal de Pediatria. 2017;93(3):260–6.

Elnasasra A, Alnsasra H, Smolyakov R, Riesenberg K, Nesher L. Ethnic diversity and increasing resistance patterns of hospitalized community-acquired urinary tract infections in Southern Israel: A Prospective Study. Israel Med Assoc J: IMAJ. 2017;19(9):538–42.

Megged O. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing bacteria causing community-acquired urinary tract infections in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(9):1583–7.

Fan N-C, Chen H-H, Chen C-L, Ou L-S, Lin T-Y, Tsai M-H, Chiu C-H. Rise of community-onset urinary tract infection caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2014;47(5):399–405.

Calbo E, Romaní V, Xercavins M, Gómez L, Vidal CG, Quintana S, Vila J, Garau J. Risk factors for community-onset urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli harbouring extended-spectrum β-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57(4):780–3.

Lob SH, Nicolle LE, Hoban DJ, Kazmierczak KM, Badal RE, Sahm DF. Susceptibility patterns and ESBL rates of Escherichia coli from urinary tract infections in Canada and the United States, SMART 2010–2014. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;85(4):459–65.

Talan DA, Takhar SS, Krishnadasan A, Mower WR, Pallin DJ, Garg M, Femling J, Rothman RE, Moore JC, Jones AE, et al. Emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase urinary tract infections among hospitalized emergency Department Patients in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77(1):32–43.

Medina-Polo J, Guerrero-Ramos F, Pérez-Cadavid S, Arrébola-Pajares A, Sopeña-Sutil R, Benítez-Sala R, Jiménez-Alcaide E, García-González L, Alonso-Isa M, Lara-Isla A, et al. Community-associated urinary infections requiring hospitalization: risk factors, microbiological characteristics and patterns of antibiotic resistance. Actas Urol Esp. 2015;39(2):104–11.

Rowe TA, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infection in older adults. Aging Health. 2013;9(5):519.

Azap ÖK, Arslan H, Şerefhanoğlu K, Çolakoğlu Ş, Erdoğan H, Timurkaynak F, Senger SS. Risk factors for extended-spectrum β-lactamase positivity in uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from community-acquired urinary tract infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(2):147–51.

Lee DS, Lee SJ, Choe HS. Community-acquired urinary tract infection by Escherichia coli in the era of antibiotic resistance. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:7656752.

Yamaji R, Rubin J, Thys E, Friedman CR, Riley LW. Persistent Pandemic Lineages of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli in a College Community from 1999 to 2017. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56(4):e01834–17. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01834-17.

Zoorob R, Grigoryan L, Nash S, Trautner BW. Nonprescription antimicrobial use in a primary care population in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(9):5527–32.

Ponce-de-Leon A, Rodriguez-Noriega E, Morfin-Otero R, Cornejo-Juarez DP, Tinoco JC, Martinez-Gamboa A, Gaona-Tapia CJ, Guerrero-Almeida ML, Martin-Onraet A, Vallejo Cervantes JL, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-negative bacilli isolated from intra-abdominal and urinary-tract infections in Mexico from 2009 to 2015: Results from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART). PLoS ONE. 2018;13(6):e0198621.

Tarlton NJ, Petrovic D-F, Frazee BW, Borges CA, Pham EM, Milton AK, Jackson N, deBoer TR, Murthy N, Riley LW. A dual enzyme-based biochemical test rapidly detects third-generation cephalosporin-resistant CTX-M-producing uropathogens in clinical urine samples. Microb Drug Resist. 2020;27:450.

Miyazaki M, Yamada Y, Matsuo K, Komiya Y, Uchiyama M, Nagata N, Takata T, Jimi S, Imakyure O. Change in the antimicrobial resistance profile of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. J Clin Med Res. 2019;11(9):635–41.

Critchley IA, Cotroneo N, Pucci MJ, Mendes R. The burden of antimicrobial resistance among urinary tract isolates of Escherichia coli in the United States in 2017. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0220265.

van Duin D, Arias CA, Komarow L, Chen L, Hanson BM, Weston G, Cober E, Garner OB, Jacob JT, Satlin MJ, et al. Molecular and clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in the USA (CRACKLE-2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):731–41.

Östholm Balkhed Å, Tärnberg M, Monstein HJ, Hällgren A, Hanberger H, Nilsson LE. High frequency of co-resistance in CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli to non-beta-lactam antibiotics, with the exceptions of amikacin, nitrofurantoin, colistin, tigecycline, and fosfomycin, in a county of Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45(4):271–8.

Zykov IN, Sundsfjord A, Småbrekke L, Samuelsen Ø. The antimicrobial activity of mecillinam, nitrofurantoin, temocillin and fosfomycin and comparative analysis of resistance patterns in a nationwide collection of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in Norway 2010–2011. Infect Dis (Lond). 2016;48(2):99–107.

Chodos AH, Kushel MB, Greysen SR, Guzman D, Kessell ER, Sarkar U, Goldman LE, Critchfield JM, Pierluissi E. Hospitalization-associated disability in adults admitted to a safety-net hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1765–72.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the SFGH clinical microbiology laboratory. ER thanks Dr. Lee Riley for his valuable guidance, the UCSF Primary Care Research Fellowship for their valuable input for early drafts of the manuscript, Yuan Hu and Cheyenne Butcher for technical assistance, and Sarah Neil for her input in final drafts of the manuscript. ER also thanks the National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program.

Funding

ER is supported by a T32HP19025 grant. This publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR001872. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ER collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. HC and MG were major contributors in design of the study and guiding analyses. ER drafted the manuscript; HC and MG edited the manuscript for clarity. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by institutional review boards from UCSF and SFGH (IRB number 19-27233).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Association between patient demographic characteristics and antimicrobial-resistant E. coli by place of care (univariate and multivariate analyses) and number of bacteriuria episodes per year.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Raphael, E., Glymour, M.M. & Chambers, H.F. Trends in prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolated from patients with community- and healthcare-associated bacteriuria: results from 2014 to 2020 in an urban safety-net healthcare system. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 10, 118 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00983-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00983-y