Abstract

In recent years concerns have been growing in the scientific community over the definition of scientific responsibilities during emergencies, and the legal status of scientists involved in the corresponding decision-making. It is clear that the legal framework is one of the main elements affecting this issue; however, many factors may affect both the specific scientific decision-making and the definition of general scientific responsibilities. The situation will vary depending on the type and scale of emergency, and from place to place, even in the same country. There will be no such thing as a single, ideal solution.

In the latest El Hierro volcanic crisis many factors have negatively affected the scientific management and have prevented an adequate definition of scientific responsibility. These factors have been detected and documented by the authors. They include excessive pressure due to human and economic issues, a poor legal framework with identifiable deficiencies, an Emergency Plan in which the Volcanic Activity/Alert Level (VAL), Emergency Response Level (ERL) and Volcanic Traffic Light (VTL) have been too rigidly linked, serious weaknesses in the management and structure of the Scientific Committee (SC), and more. Even though some of these problems have now been detected and certain solutions have already been proposed, the slowness and complexity of the bureaucratic processes are making it difficult to implement solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently the assessment of what constitutes success or failure in crisis management is still very complex and subject to heated debate (McConnell 2011). However, some volcanic crises have been considered obvious failures of management due to the large number of casualties (Chrètien and Brousse 1989; De la Cruz-Reyna and Martín Del Pozzo 2009; Voight 1990) and/or serious economic losses suffered (Aguirre and Ahearn 2007; Bostok 1978). Even when the human and economic impact is not so serious, the management process itself is always extremely complex and demanding for the actors involved in it (Cardona 1997). Conflict situations arise at different levels, generally between different scientific teams, between scientific advisers and decision-makers, and between different civil and/or military authorities involved, etc. Much has been published about many of these problems; and measures to be taken for preventing them have been proposed (Bignami et al. 2012; Newhall et al. 1999; UNDRO 1985). In some cases, the mistakes made in the past have led to the development of extensive networks of volcano monitoring, and highly-qualified teams of researchers (Bertolaso et al. 2009; Clay et al. 1999). Moreover, in some places, the Civil Defense authorities have also acquired considerable experience in dealing with large-scale emergencies, not only those due to volcanic activity but also to other types of natural hazard (Spahn et al. 2010).

The non-deterministic behavior of the observed phenomena, as in the case of weather or volcanic eruptions (Altamura et al. 2011; Doyle et al. 2014b), limits our capacity for forecasting them, even in the short-term, thus making the management of such natural hazards more difficult. Therefore, when the hazard they face is threatening a highly-populated area, scientists, Civil Defense personnel and politicians must make decisions, in real time and under uncertainty, in a context of great pressure (Marzocchi et al. 2012). In this context, the way in which the decision-makers understand the information they receive is critical because it will affect the decisions they make (Doyle et al. 2014a; Kreye et al. 2012). Following the Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) framework, some methodologies and approaches have been proposed to manage and reduce the uncertainty, not only from the point of view of data processing and hazard assessment (Aspinall and Woo 2014; Marzocchi and Jordan 2014; Marzocchi et al. 2010; Woo 2008) but also in respect of risk communication (García et al. 2014a; Potter et al. 2014). The need for awareness and a correct perception of the risk has also been highlighted (Plattner et al. 2006), as well as the importance of sustaining a strong cooperative interaction between all the key parties (scientists, public officials, stakeholders, news media and general public) to achieve an effective mitigation of the risks (Tilling 1989). It is essential, however, that these activities and decisions should take place within an adequate legal framework.

In the management of emergencies the legal framework is critical, for structuring the overall response necessary in the event of a major disaster (Eburn 2011); this framework, however, varies considerably from country to country, depending on many factors. In this context, the official Emergency Plans formulated and adopted are normally considered to be a legal document, approved often after a lengthy bureaucratic process, but usually remaining in force for several years from the initial phases of design, through various processes of updating and improvement. The Vesuvius Emergency Plan, for instance, was initiated in 1991, published for the first time in 1995, and then updated in 2001, 2003, 2007, 2008, 2012 and 2013 (Dipartimento della Protezione Civile 1995, 2013) and has been widely studied by many authors (Marzocchi et al. 2004; Neri et al. 2008; Ricci et al. 2013; Rolandi 2010; Solana et al. 2008; Zuccaro et al. 2008) The legal status of the Plan should give some clear benefits in disaster management (e.g. in defining the origin and destination of funding and other resources, assigning responsibilities for action, promoting the reactive or preventive character of the emergency plan, etc). On the other hand, however, operational flexibility in the emergency response might be reduced by the official Plan, due to the complexity of the legal framework (Dan et al. 2012; Dynes 1994), potential failures or weaknesses detected during an actual or simulated response to a major incident (Haynes 2006), deficiencies in the definitions of expected hazard scenarios (Rolandi 2010), and other issues.

It is a difficult, if not impossible, task to modify an Emergency Plan while an emergency is actually being handled; firstly because of the ongoing responsibilities and liabilities of crisis management, and secondly because, depending on the particular legislative framework, a new bureaucratic process must be initiated. Therefore the information requirements, the decision-making structure and many other factors initially incorporated in the Emergency Plan are critical for minimizing future conflicts or failures in dealing with a particular real emergency. Although the many unpredictable situations that can arise during an emergency cannot, by definition, be included in advance (Hutter 2014), the Emergency Plan must be tested when a real crisis is not taking place, through simulations in which drills or exercises can be practiced (Marreroet al. 2013).

The role and responsibilities of scientists will also vary from country to country, but sometimes such tasks can never be clearly specified, especially when scientific work must be done in contexts of high uncertainty, in places and areas where risks are high (Marzocchi et al. 2012). The case of the L’Aquila earthquake in 2009 (Cartlidge 2011; Jordan et al. 2011), has had a great impact in the scientific community, with several significant consequences; among them is a review of the legal status and limits of the scientific responsibilities (Altamura et al. 2011; Aspinall 2011; Scolobig et al. 2014). Based on the experience gained by the authors in the El Hierro volcanic crisis, discussed in this paper are several relevant factors that could hamper the correct definition of scientific responsibility. These factors include the scientific management of a volcanic crisis in a context of severe pressure, the management of the Volcanic Activity/Alert Level (VAL), Emergency Response Level (ERL) and Volcanic Traffic Light (VTL) when all these important graduated scales are included and linked in the Emergency Plan, as well as factors affecting the management of the Scientific Committee (SC).

El Hierro volcanic crisis

The 1971 eruption of the Teneguía volcano (La Palma, Canary Islands) took place in an almost uninhabited area (Carracedo et al. 2001), with a very limited impact on the population (Romero 1990). The hardly-noticed impact of the eruption of 1971 and the long period of time elapsed since have resulted in a subjective assumption of invulnerability (Douglas 1985) among the population of the Canaries. In 2004, when a new episode of unrest occurred in Tenerife (García et al. 2006; Martí et al. 2009; Pérez et al. 2007) no National, Regional or Local Volcanic Risk Plans existed, and people lacked the perception that they were living in an active volcanic territory (Dóniz-Páez et al. 2011). Nevertheless, that seismo-volcanic crisis in Tenerife led the authorities to put into action some initiatives aimed at mitigating the volcanic risk; these included the design of the Regional Emergency Plan, named PEVOLCA, which was approved in 2010 (BOC 2010), and then the first ever national Spanish Volcanic Risk Emergency Plan (BOE 2013).

In July 2011 the latest process of volcanic unrest, which started in El Hierro (Canary Islands), gave rise to substantial efforts in emergency management, including deployment of an official volcano monitoring network (López et al. 2012), analysis of real-time geophysical data (García et al. 2014a; Prates et al. 2013), activation of the recently-approved volcanic emergency plan (PEVOLCA), deployment of emergency response personnel, reinforcements to communication systems, and other measures. Since the beginning of the unrest a large volume of magma has accumulated under the island and successive magma injection processes have occurred (García et al. 2014b; García-Yeguas et al. 2014; Hernández et al. 2014). These processes are characterized by rapid increases in deformation (Prates et al. 2013), as well as by “seismic swarms” of increasing magnitudes (García et al. 2014b; Ibáñezet al. 2012). The five most important magma injection processes occurred in the following periods: 1) June-October 2011; 2) October-November 2011; 3) June-August 2012; 4) March - April 2013; and 5) December 2013 - January 2014. These processes of unrest on El Hierro show a very clear pattern of evolution (García et al. 2014b), which to date has allowed the team of scientists to forecast the increase and acceleration of activity several days in advance, before the population perceive it (García et al. 2014a).

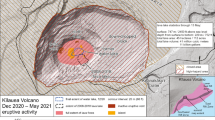

The communication strategies followed under the PEVOLCA during the El Hierro unrest are illustrated in Figure 1. PEVOLCA’s stakeholders have managed two specific procedures for communicating with the population at risk, and both are published in the media available in the region (press and TV) as well as on the Canaries Government official web site: these are the Volcano Traffic Light (VTL), with 3 colors indicating the alert status for the population, following a similar approach to that described in De la Cruz-Reyna and Tilling (2008); and the issue of Official Statements (OS) to inform about the ongoing volcanic and seismic activity. Only in the event of need for evacuation is a specific evacuation order issued, using the same available media. In accordance with this strategy, the scientific groups that comprise the Scientific Committee communicate their information to the civil authorities, but not to the public (Figure 1). It must be taken into account that the OS constitute the only official information available that is not strictly scientific. The official technical information is published on the National Geographic Institute (IGN) website (http://www.ign.es/ign/layout/volcaVolcanologia.do).

Discussion

Severe pressure on the scientific decision-making

The decision-making process in high-risk areas is conditioned by many factors; several of the most relevant are: the type and form in which the information is provided by scientists, and how well it is understood by non-scientists (Fearnley 2013; McGuire et al. 2009; Solana et al. 2008); human and economic factors applicable in the area (Aguirre and Ahearn 2007; Lane et al. 2003); risk perception (Haynes et al. 2008b); reputational and similar intangible costs for individuals and groups (Metzger et al. 1999); the treatment by the mass media of the natural phenomena in question (Birkland 1996; Francken et al. 2012); and previous experiences of similar hazards (Cardona 1997). The combination of many of these factors sometimes leads to severe pressure on the scientific decision-making process that is patently excessive and can adversely affect the scientists’ conclusions and decisions. The scientists involved, therefore, have to take into account not only the repercussions for the population when, for example, they change the alert level, but also the pressure exerted by public authorities and officials in respect of their own decisions (Fearnley 2013), especially if those authorities are not prepared or willing to deal with the human and economic consequences of such decisions (Tilling 2011). As has been highlighted by many authors (Marzocchi et al. 2012; Newhall et al. 1999; Tilling 1989), providing scientific advice in populated areas during a volcanic crisis involves stress and pressure, but this situation may be aggravated when many of the key factors noted above are having negative effects, as was the case in the El Hierro volcaniccrisis.

The volcanic crisis management in the case of El Hierro has been affected by two main groups of these relevant factors. The first comprises several closely interrelated factors, including human and economic issues, previous experience of similar hazards, and the treatment by the mass media of the natural phenomena. The second group of factors, which also affect the first group, includes changes in perceptions of the risk, and the type and form in which the information is provided by the scientists and how well it is understood by non-scientists.

Traditionally, the Canary Islands are considered a “sun, sand and sea” tourism destination (Garín-Munõz 2006) where the active volcanic nature of their territory has generally been ignored (Dóniz-Páez et al. 2011). The tourism sector in the Canary Islands depends, essentially, on the large international tour operators, and these companies can and often do divert their tourist clients to destinations considered safer or more attractive than others, and apply pressure to get discounts when the risk level increases (Cavlek 2002). This actually happened during the period of volcanic unrest on Tenerife in 2004 (Martí et al. 2009). The economic losses caused by this commercial strategy resulted in volcanic activity being regarded as an essentially prejudicial factor by the local community (Carracedo et al. 2007). This situation was repeated in El Hierro, where the mass media magnified the situation to make the story more dramatic, causing anger in many residents and some economic losses (Carracedo et al. 2012). In addition, the current general economic crisis affecting Spain, especially the public sector, has also had a negative effect on the island of El Hierro, where a large proportion of the population worked in the public sector, or was financially dependent on it, before the unrest start.

The decision-makers overreacted at the onset of the unrest, leading to considerable expenditures being incurred, due to:

-

An evident lack of experience in some of the scientists, public officials and decision-makers involved (Carracedo et al. 2012).

-

The type of volcanic activity expected in the PEVOLCA was assumed to be a short-lived process, yet the volcanic system is still active today.

-

No realistic cost-benefit analysis was conducted in advance. The PEVOLCA is a regional Emergency Plan and it does not address the planning of evacuations and other detailed actions that must be implemented by the local authorities. However, at the time, these provisions were not available, so no one had a clear idea about the total expenditures needed for the comprehensive management of a volcanic crisis.

There was also a change in the perception of the risk, before and after the submarine eruption. The island of the El Hierro island is very small (278.5 km 2) and the seismic distribution in each of the magma injection processes moved from directly underneath the island towards offshore sites (García et al. 2014b); consequently some scientific groups, as well as decision-makers, thought the probability of an eruption taking place onshore was lower than before the onset of the submarine eruption (October 2011). Therefore, after the submarine eruption ended, in March 2012, the reaction detected in the decision-makers was an inappropriate reluctance to take any decision; a wait-and-see posture was adopted and changes in the ERL, and in the warning communication system, were delayed. This lack of actions was justified by decision-makers saying that they not want to “cry wolf” or to risk creating panic in response to warnings; however, both these claimed outcomes in the communication of emergency warnings have been shown previously to be essentially myths (Atwood and Major 1998; Mileti and Sorensen 1990). The difficulties and lack of consensus among scientific groups, described in detail below, favored the wait-and-see posture of decision-makers with the result that, when the last two magma injection processes occurred (March-April 2013 and December 2013), neither were resources sent nor were protective measures taken before the more severe earthquakes (M 4.9 and M 5.4 respectively). Under these circumstances severe pressures have been exerted on the scientific decision-making procedures.

Volcanic activity level vs. emergency response levels

In the management of a volcanic crisis, the correct execution of scientific responsibilities and an adequate flexibility in the management of the emergency may be hampered or limited depending on how the relationship between the Volcanic Activity/Alert Levels (VAL) and the Emergency Response Levels (ERL) is defined in the Emergency Plan. The VAL is one of the key sub-systems of the Early Warning System (Basher 2006), and it is widely used by observatories and diverse scientific groups as a means of communication to warn the authorities and population about the ongoing or forecasted volcanic activity (UNDRO 1985). In some countries the VAL only provides information about the scientific assessment, but in others it also includes information about appropriate mitigation measures (Fearnley et al. 2012). In contradistinction, the ERL is essentially a classification system for emergencies in terms of administrative and operational response, which is implemented in general and specific Emergency Plans (York University 2011). The main criteria commonly used to define the response levels are: the severity of the expected emergency; the capacity to handle the likely incidents with local, regional or national resources; and the probable duration of the emergency and recovery time. For each level of response, the ERL defines the command structure, the resources and funds necessary, the actions to be taken, and related matters. In situations of volcanic risk the VALs are commonly managed by scientists, whereas the ERLs are managed by Civil Defense and governmental decision-makers, and the general recommendation is that the two systems should be related to each other (Bignami et al. 2012), that is, the decisions made by decision-makers should be based not only on the scientific information (Marzocchi et al. 2012), and hence on the infrastructure for providing such advice (Doswell III 2005), but also on an adequate assessment of the threatened area and the global situation.

In the PEVOLCA, a deterministic, complicated and poorly-defined VAL is rigidly linked to the ERL in the same legal document (the Emergency Plan, see Table 1); thus the scientific management of the VAL produces an almost automatic chain-reaction, which affects the whole emergency response system. It is inevitable, in such conditions, that responsibility for the actions taken in response to the emergency is placed on the scientists, although the roles of the scientists and the decision-makers are clearly different and are supposed to be separated. In addition, the misunderstanding and deficient management of the VTL also limits the operating scope of the Civil Defense personnel because, according to the Emergency Plan, they need a specific color set by decision-makers to activate the corresponding ERL.

The three available colors of the VTL signify not the level of volcanic activity but the general level of alert to which the population should be reacting, whether they should carry on as normal, just be alert, or preparing to evacuate. The VTL is not an evaluation of the natural phenomena. However, because the VTL is also linked in the Emergency Plan to both the VAL and ERL scales (Table 1), the VTL is understood and used by the decision-makers as representing the scientific definition of the expected and actual volcanic activity, as well. So the communication strategy incorporated in the PEVOLCA (Figure 1), that is, the use of the VAL (which is always very complex and difficult to manage (Fearnley 2013), for internal communication, and the VTL for communication to the public, is of reduced benefit because of the way in which they are rigidly associated in the text of the Emergency Plan. Furthermore, the legal status of the Plan document makes it impossible to redefine the scientific risks easily and rapidly. It has been seen that decision-makers try to block or delay the change of VTL color from green to yellow due to the adverse economic impact on the tourism sector in the island and because they want to avoid crying and wolf, generating panic in response to the warning, and incurring large expenditures they (or some of them) consider “unnecessary”.

Management of the Scientific Committee

In volcanic crisis management the advice will come from several different sources, such as expert individuals, panels of experts and Scientific Committees (SC) (Doyle and Johnston 2011), although in this work we refer only to the SC. From the point of view of the legal status, it is in the SC where the scientific responsibilities most evidently resided, since the designated role of its members is to provide such advice (Aspinall 2011). Therefore the performance of the SC is important, as well as the legal framework in which its activities take place. In Newhall et al. (1999) and Bignami et al. (2012) several recommendations are given to improve the SC activities during a volcanic crisis, with the object of formulating opinions to reach at least minimum degree of consensus. However, at the same time, these authors highlight numerous factors affecting the SC that can hamper this goal. Many of these factors are closely interrelated, and it is not easy to deal with them individually. The result when they act in combination determines whether the scientific decision-making and management can be considered a best-case or worst-case scenario, regardless of the magnitude and characteristics of the expected hazardous event. Some of the most important factors have been classified here at three operational levels: Individual, Internal and External (Figure 2), the first two being applicable to the personnel participating in the SC, and the third being wider issues affecting them.

At the individual level, three groups of factors are influential. The first is the professional skills (leadership, knowledge, experience, data processing skills, etc.) of members. Second is the capacity of SC members to communicate the nature of the hazards and the probabilistic character of eruption forecasting. Thirdly, their emotional and personal responses are also critical (for example, honesty, commitment, “ownership” of a volcano, respect, and temperament), because individuals involved in the SC will be under great personal pressure during a period of unrest and possible danger (Donovan and Oppenheimer 2013). Even the health condition of the SC members must be taken into account in such situations. The legal framework is directly relevant to the individuals involved in the decision-making process, and one result of this is that the behavior of these people can change the expected outcome with regard to how well the crisis is managed. However it is very complicated to conduct research on particular individuals in particular cases, to identify what was said and done by whom; yet in many cases research at the personal level is necessary to understand why today there are still numerous failures in the DRR strategy. Not only research but also drills and simulations can reveal weaknesses and help to improve an emergency plan. The analysis of risk perception by individual scientists, public officials and decision-makers can help to detect and predict future problems and weaknesses in the emergency system as a whole, as well as in respect of the individuals that comprise such a system (Donovan et al. 2014; Haynes et al. 2008b). The research questionnaires and methods used are also very important, as has been highlighted by Bird (2009).

At the internal level, the way in which the SC is managed is also very critical. This task may be the responsibility of a scientist or non-scientist, depending on the legal framework in which the SC has been designed. In a SC managed by a scientist, the manager or leader must consider how new methodologies and techniques could be incorporated, how the discussions are focused, and how resources and data are organized and shared. Mediation will be necessary between scientists; help will need to be sought from other experts; and decisions must be made on how the monitoring and field work are organized, etc (Newhall et al. 1999). In a SC managed by a non-scientist, especially if that manager lacks appropriate experience or knowledge, the discussion of complex and detailed scientific issues would not help the managers, making it necessary to conduct the discussions in such a way that the items being considered are easily understandable. Such a SC may not be competent to make decisions on important scientific questions. In Italy a combined strategy has been developed in which scientists are included with the Civil Defense staff as participants in the SC (Barberi et al. 2009). However, whatever the structure of the SC, continuous communication between scientists, decision-makers and public officials should exist to ensure good results (Jolly et al. 2014; Leonard et al. 2008). Mathematical methods using expert judgment have been used to achieve a rational consensus in a context of uncertainty (Aspinall 2006). These approaches have been incorporated in more comprehensive methodologies for hazard assessment, such as the BET_EF and BET_VH (Marzocchi et al. 2008, 2010), in which the Bayesian Belief Network for decision forecasting can handle both discrete data and/or subjective probabilities based on expert opinion (Aspinall et al. 2003). With this approach the critical factors are not only the calibration of the expert group (Bolger and Rowe 2014; Cooke 2015) but also the information that will be provided by the SC to the decision-makers (Hickey and Davis 2003). Another way to reduce disagreements between scientists is to focus the discussion on the eruptive scenarios or expected outcomes rather than on interpretation of raw data (De la Cruz-Reyna and Tilling 2008). In a volcano with frequent activity, the outcome predictions are usually more accurate, and the interpretation of monitoring data produces fewer differences of opinion; however, in volcanoes with a long period of repose, there are many more uncertainties, especially in interpreting the data. Therefore, the discussion in the SC will be more constructive if the focus is kept on the expected outcomes, and meetings should also be easier to conduct. This approach would also minimize the possible impact due to lack of experience in the scientists. Another critical aspect is the transparency in the management of the SC; for instance, established protocols should be followed, reliable meeting minutes kept, and any agreements reached should be recorded and communicated to the decision-makers (Newhallet al. 1999). The quality of the advice (forecasting, hazard assessment, mitigation strategies), how it is issued, and how well-prepared the public is to receive the advice, are important for determining not only the level of trust (Haynes et al. 2008a), but also how the perception of risk and the response of people and decision-makers will be affected (Donovan and Oppenheimer 2013; Solana et al. 2008).

At the external level, described above, the risk level, the way in which the media follow the volcanic crisis, the human and economic situation of the threatened area, and how the politicians perceive the situation may all serve to increase the pressure on scientific decision-making (Cardona 1997). However, one of the most important factors in the definition and execution of scientific responsibilities is the legal framework of the SC, which covers important aspects like funding, selection of members, duties, etc. Different cultures can lead to different legal frameworks or, from a wider perspective, different ways to deal with emergency situations (Dynes 1988; Newton 1997), sometimes even within the same country (Berke et al. 1989). There is no single ideal solution, and the introduction of standard and uniform methods might not solve the problem, as has been highlighted by Fearnleyet al. (2012).

In addition to what we have already discussed, in the particular case of the management of the SC under the El Hierro PEVOLCA, several negative factors have been identified. The long repose period resulted in some SC members and public officials being notably lacking in experience (monitoring, hazard assessment, crisis management) (Carracedo et al. 2012): the effect was that the discussions focused on the description of the available data, rather than the most probable scenarios, although the latter have been partially developed very recently (Becerril et al. 2014; Pedrazzi et al. 2014). Regrettably, scientific discrepancies were divulged to and reported by the media after the onset of the submarine eruption (October-November, 2011). These scientific discrepancies were then allowed to degenerate into personal problems, but neither the methodology of expert elicitation nor any other solution have yet been put into practice. Despite the fact that a retrospective analysis can be useful for the design and application of such methodology, when the experts selected have known the evolution of the system, this may introduce significant bias into the method; thus it is always easier to implement such a methodology retrospectively rather than in real time (Sobradelo et al. 2014).

At the internal operational level, in the case of El Hierro, the SC is managed by a non-scientist and is still controversial because there is no official record of SC meetings (absence of approved Minutes), and committee meetings have been increasingly delayed, i.e. the time that elapses between the detection of a variation in the volcanic activity and the convening of a meeting of the SC has been increasing more and more as each injection process takes place. Discrepancies have existed between the scientific decisions taken by the SC and the final information communicated to the Advisory Committee (see Figure 1), despite the fact that some decision-makers and public officials were present at meetings of both. It seems that constituting the SC within the framework of the PEVOLCA and stipulating that the SC should be managed by politicians and public officials was thought to be a strategy to control better the scientists and scientific decisions, probably in an attempt to avoid the problems that occurred during the 2004 Tenerife unrest (Carracedo et al. 2007).

At the external operational level, the El Hierro SC is part of a Regional Volcanic Emergency Plan (the PEVOLCA), which means the national Spanish Volcanic Risk Emergency Plan has also its own SC, which could give rise to a duplicated structure and contradictory decisions. Although this situation has not yet occurred (the national Spanish Volcanic Risk Emergency Plan was approved only in 2013, BOE 2013), it would be expected to occur if the volcanic activity is extended in time. The PEVOLCA only takes into account designated institutions rather than named experts (BOC 2010), and these individuals have also been changing continuously during the crisis. Hence the limits and responsibilities of scientists are not well-defined because of this complex legal framework.

Conclusions

When a crisis arises, the scientists and managers of the emergency can usually identify the most important strengths and weaknesses of the Emergency Plan (assuming one exists). However, presenting and explaining these difficulties to the wider world is a complex task. In most cases a good understanding of many local aspects is needed, and there are often several different points of view about the difficulties experienced with the plan. Nevertheless, we think it is really important to review and try to explain these difficulties if we want to improve our knowledge, and especially if we want to avoid mistakes or failures in the future.

Managing an emergency due to volcanic risk in an inhabited zone is always complex, but this circumstance is aggravated when it happens on a small island (McGuireet al. 2009; Mèheux et al. 2007). Inevitably the whole economy of the island is always going to be adversely affected. Nevertheless, a volcanic eruption does not necessarily have to be a totally negative phenomenon (Kelman and Mather 2008). El Hierro has received international attention, shown, for example, by the many times the satellite images have been viewed (http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/blogs/earthmatters/2013/04/08/longshot-captures-the-first-tournament-earth/) and the many descriptions posted by enthusiasts on the Internet (http://earthquake-report.com/?s=El+Hierro). However, strategies for assisting local tourism marketing and local business in general are not common in emergency plans; such strategies should be integrated in a global approach to the emergency, to mitigate the potential adverse economic effects of a volcanic crisis in tourism areas (Zhang et al. 2009).

In many countries, the Emergency Plan is a legal document in which responsibilities are assigned, requiring a bureaucratic process for its formulation and approval. To keep the flexibility of the Volcanic Emergency Plan and to facilitate the scientific decision-making, the ERL and VAL (and VTL, if being used), should be interrelated but not too rigidly linked as in the case of the PEVOLCA. In fact, the ERL does not need a direct relationship with the VAL: for the crisis to be well-managed, the stakeholders can make the decision about the most appropriate ERL according to the scientific information presented. This is a very important point for defining and delimiting the scientific responsibilities. In this context, the criteria used to establish and change the VAL will vary from one volcano to another (Fearnley et al. 2012) but it must be based on the best possible understanding of the physics of the phenomena (Sparks 2003). According to this, and for the scientific management of the El Hierro volcanic process, García et al. (2014a) have used a VAL based on the acceleration/deceleration of appropriate observable metrics (cumulative seismic energy and GNSS-GPS distances).

The correct definition and execution of scientific responsibilities depends not only on the legal framework. From the experience gained by the authors in the El Hierro volcanic crisis, many factors could hamper this issue. The combination of such factors could lead to the scientific management in a volcanic crisis falling anywhere between the best- and worst-case scenarios. Regrettably, the El Hierro case represents a worst-case scenario, where several factors were acting negatively: a deficient and complex legal framework; incorrect linkage between the VAL, VTL and ERL in the same legal document (the Emergency Plan); scientific discrepancies and personal problems between scientists made public by the media; management of the SC in a non-transparent way, etc. Put very simply, the worst-case scenariogenerated in El Hierro can be attributed to three very different general causes: the long repose period of the volcanic activity; the unfortunate experience in the 2004 unrest in Tenerife; and problems intrinsic to the “human factor”. Neither the appropriate forecasting process nor the available resources have facilitated the management of that volcanic crisis. It cannot be denied that significant improvement is needed to achieve an effective management of the known volcanic risk in the Canary Islands. This is especially worrying for Tenerife, where there is a potentially very dangerous volcano (Teide), on an island of just over 2000 km 2, in which one million people live (García et al. 2006; Marrero et al. 2012; Martí et al. 2008; Tárraga et al. 2008), and where no educational programs have yet been applied.

Although this topic is very subjective, according to our experience, the psychological profile of a scientist in charge should have some of the following characteristics, as has been stated before. Firstly, there are two important personality traits, honesty and humility, which are necessary for the individual to improve their own knowledge and their ability to deal with others. Secondly, good communication skills are vitally important. Thirdly, the individual must have good background knowledge and experience of the natural phenomenon to be faced, and good capacity for working under pressure. We believe, however, that a perfect profile does not exist, because the effectiveness will depend not only on the individual’s psychological profile and skills, but also on the environment in which they must operate. Both aspects will be considerably different in every case, wherever in the world the emergency may arise.

Whatever kind of emergency response system is in place, it needs to be assessed regularly to detect vulnerabilities and weaknesses, from all the many different points of view, with special emphasis not only on the legal framework and the emergency plan, but also on the individuals involved in its management. It is encouraging that current methods and methodologies provide many solutions to detect such problems and various ways to resolve them, and thus eliminate them from the emergency response system. Nevertheless, hardly any of these approaches try to deal with these weaknesses and vulnerabilities as an intrinsic part of the system: they offer possible solutions that would not change the system as a whole but would only strengthen parts of it (e.g. if an individual is the weakness and he cannot be substituted, how should this situation be dealt with?). If one wants to improve the DRR strategy, then weakness and imperfection should be considered as part of the DRR system. Whatever methodology may be adopted to assess and detect such vulnerabilities and weakness, it needs to combine both a global approach and specific local measures: the former to facilitate comparison with other situations around the world, the latter to take into account the local culture and way of life.

References

Aguirre, JA, Ahearn Megan (2007) Tourism, volcanic eruptions, and information: lessons for crisis management in National Parks, Costa Rica, 2006. PASOS, Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 5: 175.

Altamura, M, Ferraris L, Miozzo D, Musso L, Siccardi F (2011) The legal status of uncertainty. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 11(3): 797–806. doi:10.5194/nhess-11-797-2011.

Aspinall, WP (2006) Special Publications of IAVCEI, 1. Statistics in Volcanology, volume 1 of Special Publications of IAVCEI, chapter Structured Elicitation of Expert Judgment for Probabilistic Hazard and Risk Assessment in Volcanic Eruptions. Special Publications of IAVCEI, 1. Geological Society, London.

Aspinall, WP (2011) Check your legal position before advising others. Nature 477(7364): 251. doi:10.1038/477251a.

Aspinall, WP, Woo G (2014) Santorini unrest 2011–2012: an immediate Bayesian belief network analysis of eruption scenario probabilities for urgent decision support under uncertainty. J Appl Volcan 3(12): 1–12. doi:10.1186/s13617-0-0012-8.

Aspinall, WP, Woo G, Voight B, Baxter PJ (2003) Evidence-based volcanology: application to eruption crises. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 128(1): 273–285. doi:0.1016/S0377-0273(03)00260-9.

Atwood, LE, Major AM (1998) Exploring the “cry wolf” hypothesis. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 16(3): 279–302.

Barberi, F, Civetta L, Rosi M, Scandone R (2009) Chronology of the 2007 eruption of Stromboli and the activity of the Scientific Synthesis Group. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 182(3): 123–130.

Basher, R (2006) Global early warning systems for natural hazards – systematic and people-centred. Roy Soc Discuss Meeting Extreme Nat. Hazards Roy Soc London Trans Ser A 364(1845): 2167–2182.

Becerril, L, Bartolini S, Sobradelo R, Martí J, Morales JM, Galindo I (2014) Long-term volcanic hazard assessment on El Hierro (Canary Islands). Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci Discuss 2: 1799–1835. doi:10.5194/nhessd-2-1799-2014.

Berke, P, Beatley T, Wilhite S (1989) Influences on local adoption of planning measures for earthquake hazard mitigation. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 7(1): 33–56.

Bertolaso, G, De Bernardinis B, Bosi V, Cardaci C, Ciolli S, Colozza R, Cristiani C, Mangione D, Ricciardi A, Rosi M, Soddu Scalzo P (2009) Civil protection preparedness and response to the 2007, eruptive crisis of Stromboli volcano, Italy. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 182(3): 269–277. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.01.022.

Bignami, C, Bossi V, Costantini L, Cristiani C, Lavigne F, Thierry P (eds)2012. Handbook for volcanic risk management. Prevention, crisis management, resilience. European Commission under the 7th Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development, Orleans, France,p. 198.

Bird, DK (2009) The use of questionnaires for acquiring information on public perception of natural hazards and risk mitigation—a review of current knowledge and practice. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 9(4): 1307–1325. doi:10.5194/nhess-9-1307-2009.

Birkland, TA (1996) Natural disasters as focusing events: Policy communities and political response. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 14(2): 221–243.

BOC (2010) Decreto 73/2010, 1 julio, por el que se aprueba el Plan Especial de Protección Civil y Atención de Emergencias por riesgo volcánico en la Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias (PEVOLCA), Julio 2010. http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/libroazul/pdf/63689.pdf. Online, accessed: 19 April 2013 [In Spanish].

BOE (2013) Resolucioń, de 30 de enero de 2013, de la Subsecretaría, por la que se publica el Acuerdo de Consejo de Ministros de 25 de enero de 2013, por el que se aprueba el Plan Estatal de Protección Civil ante el Riesgo Volcánico, Febrero 2013. http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2013/02/11/pdfs/BOE-A-2013-1421.pdf. Online, accessed: 19 April 2013 [In Spanish].

Bolger, F, Rowe G (2014) The Aggregation of expert judgment: do good things come to those who weight?Risk Anal 2014. doi:10.1111/risa.12272.

Bostok, D (1978) A deontological code for volcanologists?J Volcanol Geotherm Res 4(1–2): 1. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(78)90026-4.

Cardona, OD (1997) Management of the volcanic crises of Galeras volcano: Social, economic and institutional aspects. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 77(1): 313–324.

Carracedo, JC, Rodríguez-Badiola ER, Guillou H, de la Nuez J Pérez-Torrado FJ (2001) Geology and volcanology of La Palma and El Hierro, Western Canaries. Estud Geol 57(5–6): 175–273.

Carracedo, Rodríguez Badiola E, Guillou H, Paterne M, Scaillet S, Pérez Torrado FJ, Paris R, Fra-Paleo U, Hansen A (2007) Eruptive and structural history of Teide Volcano and rift zones of Tenerife, Canary Islands. Geol Soc Am Bull 119(9–10): 1027–1051. doi:10.1130/B26087.1.

Carracedo, JC, Pérez-Torrado F, Rodríguez-González A, Soler V, Fernández-Turiel JL, Troll VR, Wiesmaier S (2012) The 2011 submarine volcanic eruption in El Hierro (Canary Islands). Geol Today 28(2): 53–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2451.2012.00827.x.

Cartlidge, E (2011) Quake experts to be tried for manslaughter. Science 332: 1135–1136. doi:10.1126/science.332.6034.1135.

Cavlek, N (2002) Tour operators and destination safety. Ann Tourism Res 29(2): 478–496. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00067-6.

Chrètien, S, Brousse R (1989) Events preceding the great eruption of 8 May, 1902, at Mount Pelèe, Martinique. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 38(1–2): 67–75. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(89)90030-9.

Clay, E, Barrow C, Benson C, Dempster J, Kokelaar P, Pillai N, Seaman J (1999) An evaluation of HMG’s response to the montserrat volcanic emergency. Evaluation report ev635 Department for International Development, December 1999. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67966/ev635.pdf.

Cooke, RM (2015) The aggregation of expert judgment: do good things come to those who weight?Risk Anal. doi:10.1111/risa.12353.

Dan, L, Hong-Wei W, Chao Q, Jian W (2012) ORECOS: an open and rational emergency command organization structure under extreme natural disasters based on China’s national conditions. Disaster Adv 5(4): 63–73.

De la Cruz-Reyna, S, Martín Del Pozzo AL (2009) The 1982 eruption of El Chichón volcano, Mexico: eyewitness of the disaster. Geofis Int 48: 21–31.

De la Cruz-Reyna, S, Tilling RI (2008) Scientific and public responses to the ongoing volcanic crisis at Popocatépetl Volcano, Mexico: importance of an effective hazards-warning system. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 170(1): 121–134. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2007.09.002.

Dipartimento della Protezione Civile (1995) Pianificazione nazionale d’emergenza dell’area Vesuviana, Prefettura di Napoli, September, 1995. http://www.protezionecivile.gov.it/resources/cms/documents/1995_PIANO.pdf. Online, accessed: 20 May 2014.

Dipartimento della Protezione Civile (2013) Aggiornamento del Piano nazionale di emergenza per il Vesuvio, 2013. http://www.protezionecivile.gov.it/jcms/it/view_dossier.wp?contentId=DOS37087. Online, accessed: 20 May 2014.

Dóniz-Páez, J, Becerra-Ramírez R, González-Cárdenas E, Guillén-Martín C, Escobar-Lahoz E (2011) Geomorphosites and Geotourism in Volcanic Landscapes: the example of La Corona del Lajial cinder cone (El Hierro, Canary Islands, Spain). GeoJournal Tourism GeositesIV(2–8): 185–197.

Donovan, A, Oppenheimer C (2013) Science, policy and place in volcanic disasters: Insights from Montserrat. Environ Sci Policy 39: 150–161. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2013.08.009.

Donovan, A, Eiser JR, Sparks RSJ (2014) Scientists’ views about lay perceptions of volcanic hazard and risk. J Appl Volcan 3(1): 1–14. doi:10.1186/s13617-014-0015-5.

Doswell CA, III (2005) Progress toward developing a practical societal response to severe convection (2005, EGU Sergei Soloviev Medal Lecture). Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 5(5): 691–702. doi:10.5194/nhess-5-691-2005.

Douglas, M (1985) Risk acceptability according to the social sciences, volume XI. Russell Sage Foundation Publications Abingdon.

Doyle, EE, Johnston D (2011) Science advice for critical decision-making. In: Paton D Violanti J (eds)Working in high risk environments: developing sustained resilience, chapter 5. Charles C Thomas, 69–92.. Springfield.

Doyle, EEH, McClure J, Johnston DM, Paton D (2014a) Communicating likelihoods and probabilities in forecasts of volcanic eruptions. J Volcanol Geoth Res 272(0): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2013.12.006.

Doyle, EEH, McClure J, Paton D, Johnston DM (2014b) Uncertainty and decision making: volcanic crisis scenarios. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 10: 75–101. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.07.006.

Dynes, RR (1994) Community emergency planning: false assumptions and inappropriate analogies. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 12(2): 141–158.

Dynes RR (1988) Cross-cultural international research: sociology and disaster. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 6(2): 101–129.

Eburn, M (2011) Responding to catastrophic natural disasters and the need for Commonwealth Legislation. Canberra Law Review 10(3): 81–102.

Fearnley, CJ (2013) Assigning a volcano alert level: negotiating uncertainty, risk, and complexity in decision-making processes. Environ Plann A 45(8): 1891–1911. doi:10.1068/a4542.

Fearnley, CJ, McGuire WJ, Davies G, Twigg J (2012) Standardisation of the USGS Volcano Alert Level System (VALS): analysis and ramifications. Bull Volcanol 74(9): 2023–2036. doi:10.1007/s00445-012-0645-6.

Francken, N, Minten B, Swinnen JFM (2012) The political economy of relief aid allocation: evidence from Madagascar. World Dev 40(3): 486–500. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.007.

García, A, Berrocoso M, Marrero JM, Fernández-Ros A, Prates G, De la Cruz-Reyna S, Ortiz R (2014a) Volcanic Alert Level System (VALS) developed during the (2011–2013) El Hierro (Canary Island) volcanic process. Bull Volcanol 76: 825. doi:10.1007/s00445-014-0825-7.

García, A, Fernández-Ros A, Berrocoso M, Marrero JM, Prates G, De la Cruz-Reyna S, Ortiz R (2014b) Magma displacements under insular volcanic fields, applications to eruption forecasting: El Hierro, Canary Islands, 2011–2013. Geophys J Int 196: 1–13. doi:10.1093/gji/ggt505.

García, A, Vila J, Ortiz R, Marcía R, Sleeman R, Marrero JM, Sánchez N, Tárraga M, Correig AM (2006) Monitoring the reawakening of Canary Islands’ Teide Volcano. Eos Trans AGU 87(6): 61–65. doi:10.1029/2006EO060001.

García-Yeguas, A, Ibáñez JM, Koulakov I, Jakovlev A, Carmen Romero-Ruiz M, Prudencio J (2014) Seismic tomography model reveals mantle magma sources of recent volcanic activity at El Hierro Island (Canary Islands, Spain). Geophys J Int 199(3): 1739–1750. doi:10.1093/gji/ggu339.

Garín-Munõz, T (2006) Inbound international tourism to Canary Islands: a dynamic panel data model. Tourism Manage 27: 281–191. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2004.10.002.

Haynes, K (2006) Volcanic island in crisis: investigating environmental uncertainty and the complexities it brings. Aust J Emerg Manage 21(4): 21–28.

Haynes, K, Barclay J, Pidgeon N (2008a) The issue of trust and its influence on risk communication during a volcanic crisis. Bull Volcanol 70(5): 605–621. doi:10.1007/s00445-007-0156-z.

Haynes K, Barclay J, Pidgeon N (2008b) Whose reality counts? Factors affecting the perception of volcanic risk. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 172(3): 259–272.

Hernández, PA, Calvari S, Ramos A, Pérez NM, Márquez A, Quevedo R, Barrancos J, Padrón E, Padilla GD, López D, Rodríguez-Santana A, Melián GV, Dionis S, Rodríguez F, Calvo D, Spampinato L (2014) Magma emission rates from shallow submarine eruptions using airborne thermal imaging. Rem Sens Environ 154: 219–225. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2014.08.027.

Hickey, AM, Davis AM (2003) Elicitation technique selection: how do experts do it? In: Requirements engineering conference, 11th IEEE international, 169–178.. IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICRE.2003.1232748.

Hutter, B (2014) Lessons for Government in Minimising Risk: what can the public service learn from the private sector? In: Boston J, Wanna J, Lipski V, Pritchard J (eds)Future-proofing the state. Managing risks, responding to crises and building resilience, chapter 9, 103–114.. Australian National University Press, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia.

Ibáñez, JM, De Angelis S, Díaz-Moreno A, Hernández P, Alguacil G, Posadas A, Pérez N (2012) Insights into the 2011–2012, submarine eruption off the coast of El Hierro (Canary Islands, Spain) from statistical analyses of earthquake activity. Geophys J Int 191(2): 659–670. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05629.x.

Jolly, GE, Keys HJR, Procter JN, Deligne NI (2014) Overview of the co-ordinated risk-based approach to science and management response and recovery for the 2012, eruptions of Tongariro volcano, New Zealand. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 286: 184–207. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2014.08.028.

Jordan, TH, Chen Y-T, Gasparini P, Madariaga R, Main I, Marzocchi W, Papadopoulos G, Sobolev G, Yamaoka K, Zschau J (2011) Operational earthquake forecasting. State of knowledge and guidelines for utilization. Ann Geophys-Italy 54(4): 315–391. doi:10.4401/ag-5350.

Kelman, I, Mather TA (2008) Living with volcanoes: the sustainable livelihoods approach for volcano-related opportunities. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 172: 189–198. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2007.12.007.

Kreye, ME, Goh YM, Newnes LB, Goodwin P (2012) Approaches to displaying information to assist decisions under uncertainty. Omega 40(6): 682–692. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2011.05.010.

Lane, LR, Tobin GA, Whiteford LM (2003) Volcanic hazard or economic destitution: hard choices in Baños, Ecuador. Global Environ Change B Environ Hazards 5(1): 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.hazards.2004.01.002.

Leonard, GS, Johnston DM, Paton D, Christianson A, Becker J, Keys H (2008) Developing effective warning systems: ongoing research at Ruapehu volcano, New Zealand. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 172(3): 199–215.

López, C, Blanco MJ, Abella R, Brenes B, Rodríguez-Cabrera VM, Casas B, Domínguez Cerdeña I, Felpeto I, de Villalta F, del Fresno C, García O, García-Arias MJ, García-Cañada L, Gomis-Moreno A, González-Alonso E, Guzmán-Pérez J, Iribarren I, López-Díaz R, Luengo-Oroz N, Meletlidis S, Moreno M, Moure D, Pereda de Pablo J, Rodero C, Romero E, Sainz-Maza S, Sentre-Domingo MA, Torres PA, Trigo P, Villasante-Marcos V (2012) Monitoring the volcanic unrest of El Hierro (Canary Islands) before the onset of the 2011–2012, submarine eruption. Geophys Res Lett 39: L13303. doi:10.1029/2012GL051846.

Marrero, JM, García A, Llinares A, Rodriguez-Losada JA, Ortiz R (2012) A direct approach to estimating the number of potential fatalities from an eruption: application to the Central Volcanic Complex of Tenerife Island. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 219: 33–40. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.01.008.

Marrero, JM, García A, Llinares A, De la Cruz-Reyna S, Ramos S, Ortiz R (2013) Virtual Tools for volcanic crisis management, and evacuation decision support: applications to El Chichón volcano (Chiapas, México). Nat Hazards 68: 955–980. doi:10.1007/s11069-013-0672-4.

Martí J, Geyer A, Andujar J, Teixidó F, Costa F (2008) Assessing the potential for future explosive activity from Teide–Pico Viejo stratovolcanoes (Tenerife, Canary Islands). J Volcanol Geotherm Res 178(3): 529–542. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.07.011.

Martí J, Ortiz R, Gottsmann J, García A, De La Cruz-Reyna S (2009) Characterising unrest during the reawakening of the central volcanic complex on Tenerife, Canary Islands, 2004–2005, and implications for assessing hazards and risk mitigation. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 182(1): 23–33. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.01.028.

Marzocchi, W, Jordan TH (2014) Testing for ontological errors in probabilistic forecasting models of natural systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(33): 11973–11978. doi:10.1073/pnas.1410183111.

Marzocchi, W, Sandri L, Selva J (2008) BET_EF: a probabilistic tool for long-and short-term eruption forecasting. Bull Volcanol 70(5): 623–632. doi:10.1007/s00445-007-0157-y.

Marzocchi, W, Newhall C, Woo G (2012) The scientific management of volcanic crises. J Volcanol Geotherm Res247–248: 181–189. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.08.016.

Marzocchi, W, Sandri L, Selva J (2010) BET_VH: a probabilistic tool for long-term volcanic hazard assessment. Bull Volcanol 72(6): 705–716. doi:10.1007/s00445-010-0357-8.

Marzocchi, W, Sandri L, Gasparini P, Newhall C, Boschi E (2004) Quantifying probabilities of volcanic events: the example of volcanic hazard at Mount Vesuvius. J Geophys Res 109(B11): B11201. doi:10.1029/2004JB003155.

McConnell, A (2011) Success? Failure? Something in-between? A framework for evaluating crisis management. Pol Soc 30(2): 63–76. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2011.03.002.

McGuire, WJ, Solana MC, Kilburn CRJ, Sanderson D (2009) Improving communication during volcanic crises on small, vulnerable islands. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 183(1–2): 63–75.

Mèheux, K, Dominey-Howes D, Lloyd K (2007) Natural hazard impacts in small island developing states: a review of current knowledge and future research needs. Nat Hazards 40(2): 429–446.

Metzger, P, D’Ercole R, Sierra A (1999) Political and scientific uncertainties in volcanic risk management: the yellow alert in Quito in October 1998. GeoJournal 49(2): 213–221.

Mileti, DS, Sorensen JH (1990) Communication of emergency public warnings. Report ORNL-6609, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Washington. DC. August 1990, http://emc.ed.ornl.gov/publications/PDF/CommunicationFinal.pdf.

Neri, A, Aspinall WP, Cioni R, Bertagnini A, Baxter PJ, Zuccaro G, Andronico D, Barsotti S, Cole PD, Ongaro TE, Hincks TK, Macedonio G, Papale P, Rosi M, Santacroce R, Woo G (2008) Developing an Event Tree for probabilistic hazard and risk assessment at Vesuvius. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 178(3): 397–415.

Newhall, C, Aramaki S, Barberi F, Blong R, Calvache M, Cheminee JL, Punongbayan R, Siebe C, Simkin T, Sparks R, Tjetjep W (1999) Professional conduct of scientists during volcanic crises. Bull Volcanol 60: 323–334.

Newton, J (1997) Federal legislation for disaster mitigation: a comparative assessment between Canada and the United States. Nat Hazards 16(2–3): 219–241. doi:10.1023/A:1007976800302.

Pedrazzi, D, Becerril L, Mart’ı J, Meletlidis S, Galindo I (2014) Explosive felsic volcanism on El Hierro (Canary Islands). Bull Volcanol 76: 863. doi:10.1007/s00445-014-0863-1.

Pérez, NM, Hernández PA, Padrón E, Melián G, Marrero R, Padilla G, Barrancos J, Nolasco D (2007) Precursory subsurface 222Rn and 220Rn degassing signatures of the 2004, seismic crisis at Tenerife, Canary Islands. Pure Appl Geophys 164(12): 2431–2448. doi:10.1007/s00024-007-0280-x.

Plattner Th, Plapp T, Hebel B (2006) Integrating public risk perception into formal natural hazard risk assessment. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 6(3): 471–483. doi:10.5194/nhess-6-471-2006.

Potter, SH, Jolly GE, Neall VE, Johnston DM, Scott BJ (2014) Communicating the status of volcanic activity: revising New Zealand’s Volcanic Alert Level System. J Appl Volcan 3: 13. doi:10.1186/s13617-014-0013-7.

Prates, G, García A, Fernández-Ros A, Marrero JM, Ortiz R, Berrocoso M (2013) Enhancement of sub-daily positioning solutions for surface deformation surveillance at El Hierro volcano (Canary Islands - Spain). Bull Volcanol 75(6): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s00445-013-0724-3.

Ricci, T, Nave R, Barberi F (2013) Vesuvio civil protection exercise MESIMEX: survey on volcanic risk perception. Ann Geophys-Italy 56(4): S0452. doi:10.4401/ag-6458.

Rolandi, G (2010) Volcanic hazard at Vesuvius: An analysis for the revision of the current emergency plan. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 189(3): 347–362. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.08.007.

Romero, C (1990) Las manifestaciones volcanicas históricas del Archipiélago Canarió, PhD thesis, Universidad de la Laguna. La Laguna, Tenerife.

Scolobig, A, Mechler R, Komendantova N, Liu W, Schröter D, Patt A (2014) The co-production of scientific advice and decision making under uncertainty: lessons from the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake, Italy. Planet@Risk 2(2): 71–76. Davos: Global Risk Forum GRF Davos.

Sobradelo, R, Martí J, Kilburn J, López C (2014) Probabilistic approach to decision-making under uncertainty during volcanic crises: retrospective application to the El Hierro (Spain) 2011, volcanic crisis. Nat Hazards: 1–20. doi:10.1007/s11069-014-1530-8.

Solana, MC, Kilburn CRJ, Rolandi G (2008) Communicating eruption and hazard forecasts on Vesuvius, Southern Italy. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 172(3): 308–314.

Spahn, H, Hoppe M, Vidiarina HD, Usdianto B (2010) Experience from three years of local capacity development for tsunami early warning in Indonesia: challenges, lessons and the way ahead. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 10(7): 1411–1429. doi:10.5194/nhess-10-1411-2010.

Sparks, RSJ (2003) Forecasting volcanic eruptions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 210(1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00124-9.

Tárraga, M, Carniel R, Ortiz R, García A (2008) Chapter 13 the failure forecast method: review and application for the real-time detection of precursory patterns at reawakening volcanoes. Dev Volcano 10: 447–469. doi:10.1016/S1871-644X(07)00013-7.

Tilling, RI, Tilling RI (1989) Scientific and public response In: Volcanic Hazards, volume 1, chapter 6, 103–106.. Wiley Online Library. doi:10.1029/SC001p0025.

Tilling, RI (2011) Volcanic hazards and early warning. In: Meyers RA (ed)Extreme environmental events. Complexity in forecasting and early warning, volume 1 of selected entries from the encyclopedia of complexity and system science, 1135–1145.. Springer-Verlag, New York.

United Nations Disaster Relief Coordinator UNDRO (1985) Volcanic emergency management. United Nations, New York.

Voight (1990) The 1985 Nevado del Ruiz volcano catastrophe: anatomy and retrospection. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 42: 151–188. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(90)90027-D.

Woo, G (2008) Probabilistic criteria for volcano evacuation decisions. Nat Hazards 45(1): 87–97. doi:10.1007/s11069-007-9171-9.

York University (2011) York University emergency plan, August. http://www.yorku.ca/epp/documents/YorkUniversityEmergencyPlan.pdf. Online, accessed: 12 Jun 2014.

Zhang, Y, Lindell MK, Prater CS (2009) Vulnerability of community businesses to environmental disasters. 331: 38–57. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01061.x.

Zuccaro, G, Cacace F, Spence RJS, Baxter PJ (2008) Impact of explosive eruption scenarios at Vesuvius. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 178(3): 416–453. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.01.005.

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by the CSIC (201130E070) and MINECO (CGL2011-28682- C02-01) research projects. We wish to thank all of the people living on El Hierro for their encouragement and understanding of our scientific work. Grateful acknowledgement is made to Dr/Mr. Royston Snart for the very good translation and accurate/insightful comments. Finally we thank everyone who has participated in any aspect of the El Hierro volcanic process management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in the conceptual design of the study, and in drafting and revising the manuscript, using the experience acquired in other volcanic crises and during the El Hierro volcanic process. All the authors have worked on the island of El Hierro during the unrest process and the main critical situations of increasing activity. During the whole volcanic process this team has maintained continuous contact with the population and authorities of the island. They have carried out field surveys using the team’s own instrumentation, data process, scenarios design and forecasting models. RO and AG are permanent members of the SC of the PEVOLCA and MB invited member. JM and AL coordinated the writing of the paper and prepared all related materials. All the authors have read, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marrero, J.M., García, A., Llinares, Á. et al. Legal framework and scientific responsibilities during volcanic crises: the case of the El Hierro eruption (2011–2014). J Appl. Volcanol. 4, 13 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-015-0028-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-015-0028-8