Abstract

Chemotherapy has made an essential contribution to cancer treatment in recent decades despite its adverse effects. As cancer survivors have increased, concern about ex-patient lifespan has become more important too. Doxorubicin is an effective anti-neoplastic drug that produces a cardiotoxic effect. Cancer survivors who received doxorubicin became more vulnerable to cardiac disease than the normal population did. Many efforts have been made to prevent cardiac toxicity in patients with cancer. However, current therapies cannot guarantee permanent cardiac protection. One of their main limitations is that they do not promote myocardium regeneration. In this review, we summarize and discuss the promising use of mesenchymal stem cells for cardio-protection or cardio-regeneration therapies and consider their regenerative potential without leaving aside their controversial effects on tumor progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, cancer is the leading cause of death. There were 14.1 million new cases of cancer in 2012, and an increase of up to 22.2 million new cases by 2030 is predicted [1]. On the other hand, the advances in diagnostic methods for early detection of tumors and the associated treatments have increased the cancer survival rate of the global population [2].

Chemotherapy is an essential tool in cancer treatment. However, the use of anti-neoplastic agents has several adverse effects. Doxorubicin, which belongs to the anthracycline family, has been proven to be effective in different tissue-derived cancer diseases, including cancer of the breast, lung, stomach, bladder, and skin. Despite the anti-tumoral properties of doxorubicin, myelosuppression and particularly cardiotoxicity restrict its clinical use [3].

Doxorubicin has been used in oncology treatment since the 1970s. So far, the following risk factors for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity have been reported: female gender, pre-existing cardiac diseases, mediastinal radiation, cumulative anthracycline doses, and co-treatments with 5-fluorouracil, cyclophosphamide, or taxanes [4].

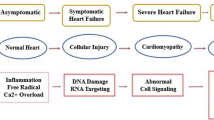

Cardiomyopathy induced by doxorubicin was described at an early stage (that is, during the first 30 days after the start of treatment) with an incidence of 1 % to 2 % and also several years after the end of drug administration [3]. In fact, retrospective clinical studies estimate that within 30 years after cancer treatment, survivors are eight times more likely to die from cardiac causes and 15 times more likely to be diagnosed with congestive heart failure [5]. This long-term cardiotoxic effect is an especially relevant threat to the survivors of childhood cancer. For this reason, the quality of life of cancer survivors becomes an important issue that promotes the investigation of new monitoring strategies for early diagnosis and multi-agent preventive treatments [6].

In this review, we describe the doxorubicin cardiomyopathy at molecular, histological, and functional levels and the strategies to prevent and monitor cardiac damage. Currently, the cardioprotective treatments based on medical guidelines have limitations, which drive researchers to find new ways to solve them. We discuss the potential of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy to prevent the cardiotoxicity induced by doxorubicin, its incipient and promising results, and the uncertainty about its use in patients with cancer.

Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy

Pharmacokinetics studies have demonstrated that doxorubicin has a triphasic plasma clearance after intravenous injection, suggesting that doxorubicin uptake is faster than its elimination from the tissues. For this reason, the risk of toxicity depends directly on the steady-state distribution of the drug [7]. Doxorubicin is accumulated mostly in the liver, due to its role in metabolism, followed by the kidney and heart [8]. In addition, pharmacokinetics analysis has shown the distribution of doxorubicin in different tissues in animal models, providing relevant information to better understand the variability of the outcomes in cancer therapy. Studies of tissue distribution of doxorubicin have demonstrated that the dissemination of the drug in cancer tissue is different than in normal tissue for multi-agent factors; for instance, uneven regional vessel distribution in subcutaneous tumors derived from MDA-MB-231 cells, in athymic nude mice, reduced doxorubicin delivery and interaction with cancer cells [8]. Therefore, this vascular factor may produce drug-resistance phenotype in tumors.

Doxorubicin passes through cell membranes by passive diffusion. Inside the cells, doxorubicin accumulates principally in the nucleus and mitochondria (two orders of magnitude) in comparison with the cytoplasmic concentration [9]. The doxorubicin-anti-neoplastic effect is based on its intercalation into DNA and inhibition of a key enzyme (topoisomerase II) for the DNA replication process [10], killing cells under active proliferation, such as cancer cells. The specific mechanisms of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity are complex and remain unclear. However, these mechanisms are related mainly to the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the mitochondria that cause cellular oxidative stress [11]. Mitochondrial ROS production occurs mainly by NADH dehydrogenase oxidation of doxorubicin and chelation with Fe2+ [12]. The heart is particularly sensitive to doxorubicin because it has a high density of mitochondria per cardiomyocyte and low capacity for cellular regeneration (compared with other tissues). As a direct and indirect consequence of oxidative stress, doxorubicin impairs Ca2+ signaling in mitochondria and sarcoplasmatic reticulum, altering the contraction cycle in cardiomyocytes, producing lipid peroxidation in cell membranes, and inhibiting transcription processes. These effects downregulate the expression of cardiac muscle-specific proteins (for example, myosin light and heavy chains) and mitochondrial proteins (for example, ADP/ATP translocase), leading the cardiomyocyte to a loss of contraction force by mechanical and energetic causes [13].

Huang and colleagues [14], using a pediatric animal model of late-onset doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, concluded that, besides the toxic effects in cardiomyocytes, doxorubicin impaired cardiac progenitor cell (CPC) proliferation and differentiation into cells of cardiac lineages. Moreover, Piegari and colleagues [15] reported that doxorubicin produces a premature senescence in human CPCs (c-kit+) and their progeny, reducing regenerative capacity of the heart. On the other hand, De Angelis and colleagues [16] reported that CPC administration improved the cardiac function in an animal model of dilated cardiomyopathy induced by doxorubicin administration. This doxorubicin cytotoxic effect could explain the increased susceptibility of cancer survivors to develop a cardiac disease after many years of anti-cancer drug treatment.

In regard to the mechanism of apoptosis induced by doxorubicin, there is a consensus on the main role of oxidative stress to activate cell death signal pathways. In vitro studies using H9c2 myoblast have shown that oxidative stress induced by doxorubicin activates AMPK (a protein kinase considered to be an intracellular sensor of the energy status) that interacts with p53, leading to bax/bad translocation from cytosol to mitochondria and promoting the release of cytochrome c and caspases activation [17,18]. On the other hand, it was reported that doxorubicin downregulates the expression of bcl-2, a protein known for its anti-apoptotic properties. The bax/bcl-2 complex has crucial importance in the cell destiny - survival or death - during doxorubicin treatment [19,20]. Oxidative stress is also involved in the activation of the apoptotic pathway p38-MAPK/NF-κB and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in H9c2 cells [21].

Doxorubicin also produces oxidative stress in endothelial cells, leading to an increase in endothelial permeability by reduction of nitric oxide production, pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, and the expression of adhesion molecules [22]. Leukocyte infiltration and neutrophil activation lead to further cytokine secretion, protease release, and oxidative stress production, thereby exacerbating myocardial injury and death [23].

In this way, doxorubicin triggers a cardiac inflammatory response, in which several mechanisms of innate immune response are activated. To find the key molecules involved in doxorubicin-induced inflammation, researchers have used several strategies, including neutralizing antibodies to specific receptors (for instance, Toll-like receptor 4, or TLR4) [24], knockout mice (for example, TLR4 or STAT3) [25,26], or inhibitory agents for the synthesis of pro-inflammatory molecules (for example, prostaglandin E2, or PGE2) [27]. The results of these experiments have a common conclusion; when the pro-inflammatory response induced by doxorubicin was inhibited, cardiac function was significantly improved, suggesting that the exacerbated response of the immune system accentuated heart damage.

Currently, under a myocardium cell death process in an inflammatory microenvironment, collagen fiber synthesis is promoted, constituting the whole picture of histological markers in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: loss of muscle fiber, sarcoplasmatic distention, vacuolization of cardiomyocytes, and fibrosis [28].

In adult patients, the structural and functional changes induced by doxorubicin toxicity progress mainly to dilated cardiomyopathy, which is defined as an increase in left ventricle (LV) dimension, thinness of LV walls, and a severe loss of contractility. However, in pediatric patients, a restrictive cardiomyopathy described by normal dimension and wall thickness of LV and an enlargement of auricle and hardening of cardiac muscle generating diastolic dysfunction is more frequent [29].

Monitoring and treatments to prevent doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity

According to current medical guidelines, monitoring of cardiotoxicity for doxorubicin dose (in milligrams per square meter) is performed with echocardiography and multiple gated acquisition scan. A reduction of 10 % in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) from 50 % (basal) is sufficient to suspend the oncologic treatment [30]. However, these non-invasive methods do not detect early heart injury to prevent subsequent cardiac dysfunction or predict patient tolerance to doxorubicin. Therefore, the identification of new biomarkers has been investigated with promising results. Ky and colleagues [31] proposed that early increases of cardiac troponin I and myeloperoxidase biomarkers are useful to estimate the degree of tolerance of each patient to an oncology treatment for breast cancer. Desai and colleagues [32] identified plasmatic microRNAs (miR-34a and miR-150) that correlated with heart injury in a pre-clinical model; this finding may lead to the development of new biomarkers for earlier events in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity before the release of cardiac troponins.

Prevention of cardiotoxicity is managed mainly by monitoring the maximum cumulative dose (that is, 300 to 350 mg/m2 for adults and 200 to 250 mg/m2 for children [33]) and by using alternative methods for drug delivery, such as pegylated or non-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, that increase the half-life of the molecule in plasma, reducing cardiac injury. However, patients usually undergo the uncomfortable adverse effects of plantar-palmar erythrodysesthesia and deeper myelosuppression [34]. An alternative to reducing the cardiotoxic effects of doxorubicin is the co-administration of the drug with iron-chelating agents such as dexrazozane; however, its use is restricted to particular cases of adult patients because data from clinical trials in which the administration of this drug enhances the myelosuppressive effects and interferes with the anti-tumor therapy of doxorubicin have been reported [9,35].

Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity is frequently refractory to conventional pharmacologic therapies for cardiac ischemic diseases. Βeta-blockers (for example, metoprolol) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (for example, enalapril) are useful to attenuate doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy; however, long-term administration should be balanced with their adverse effects such as hypotension, fatigue, and dizziness since their beneficial effects are only transient [36].

Cell-based therapies for cardiac diseases

Cell-based therapies have a huge potential to treat cardiovascular diseases because of their regenerative properties and safety. Until 2013, approximately 2,000 patients had been enrolled in clinical trials around the world to evaluate different kinds of stem cell therapies showing promising results [37]. In regard to the cell sources, embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are attractive for therapy applications. ESCs can differentiate into cardiomyocytes, which can integrate into the host cardiac tissue and improve the functional performance in animal models of heart damage. However, the ESCs used in pre-clinical trials have strong bioethical restrictions because it is necessary to destroy human embryos for their generation. Additional complications regarding the use of ESCs include the possibility of teratoma formation in the host and the necessary life-long immunosuppressive therapy to prevent graft rejection [38]. In 2006, Takahashi and Yamanaka [39] described a procedure to induce pluripotency in somatic cells, generating a new kind of stem cells with a wide differentiation potential, called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Mauritz and colleagues [40] showed that cardiomyocyte administration, obtained from in vitro differentiation of iPSCs, improved the cardiac function in an animal model of infarcted heart, suggesting a promising future for iPSC-based therapy. iPSC therapy has the advantage of being free of ethical restrictions; however, owing to their ESC-like properties, they could be tumorigenic [41]. As a result, more investigations are needed to identify new differentiation and purification protocols before they can be used in clinical trials. In 2003, Beltrami and colleagues [42] reported that the adult heart contains CPCs that support the cardiac regeneration process because of their ability to differentiate into cardiomyocyte or endothelial cells. These cells, isolated from cardiac human biopsies, have the capacity to be highly expanded ex vivo, allowing their use in cell-based therapy protocols [43]. The regeneration potential of CPCs was demonstrated in animal models of myocardial infarct [44]. At present, CPC-based therapy is being evaluated with favorable results in two clinical trials: SCIPIO (Stem Cell Infusion in Patients with Ischemic Cardiomyopathy) and CADUCEUS (Cardiosphere-Derived Autologous Stem Cells to Reverse Ventricular Dysfunction), the latter in patients with acute myocardial infarct [45–47]. Finally, clinical or pre-clinical studies (or both) testing new treatments for cardiac regeneration have been reported with the use of adult MSCs, including bone marrow MSCs (BMMSCs), adipose tissue-derived MSCs (ASCs), and MSCs from human umbilical cord blood (hUCBs). In this review, we will focus the discussion on MSC therapies.

MSCs have many characteristics that make them a suitable tool for preventive or regenerative myocardium therapies (or both), including prevention of doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. MSCs are self-renewal cells with the potential to differentiate into cells of the adipogenic, osteogenic, and condrogenic lineages. Moreover, in in vivo and in vitro models, MSCs can express specific cardiomyocyte markers (for example, connexin 43 and N-cadherin) [48,49]. However, when MSCs were administered by either local or systemic routes, their myocardial homing capacity was weak. For this reason, it is accepted that differentiation into cardiomyocyte is not a relevant mechanism in myocardium regeneration [50]. On the other hand, it was reported that MSCs are attracted to the damaged organs by a chemotaxis process in which MSCs recognize molecules overexpressed in damaged tissues - for example, stromal cell-derived factor-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 - by interaction with the C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 and 1 and chemokine receptor type 2 surface receptors [50], leading to a selective homing after systemic administration.

MSCs secrete paracrine factors such as insulin-like growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, endothelin-1, and basic fibroblast growth factor (with proliferative and anti-apoptotic properties), vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor (with angiogenic properties), and matrix metallopeptidase-9 (with anti-fibrotic properties) [51,52]; all are involved in the regenerative and cardiac remodeling process. Indeed, MSCs stimulate host CPC proliferation and differentiation and enhance cardiomyocyte cell cycling, mechanisms that could attenuate the long-term cardiotoxic effect of doxorubicin [53,54].

MSCs have been defined as hypoimmunogenic cells because they are not rejected by the recipient’s immune system, even if they come from a non-histocompatible individual [55], allowing allogeneic transplantation therapies.

MSCs also have anti-inflammatory properties through the activation, suppression, migration, or differentiation of specific immune system cells, including T cells, natural killer cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils, by the secretion of several immune regulators, including transforming growth factor-beta, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, PGE2, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase [56]. The role played by MSCs inside the myocardium during the inflammatory process (induced by infection, metabolic disorders, or chemotherapies) is very difficult to elucidate; however, it is known that Toll-like receptors (for example, TLR3 and TLR4) expressed in MSCs have a key role in the modulation of the inflammatory process [57].

In regard to oxidative stress, the main cause of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, it was reported that MSCs could manage elevated tissue oxidative stress by reducing ROS-induced apoptosis and modifying the redox microenvironment [58]. Finally, given their technical aspects, MSCs have the advantage that their isolation and ex vivo expansion are quite simple and secure from external contamination [59].

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for doxorubicin cardiomyopathy

In regard to the development of cell-based therapies to prevent doxorubicin cardiotoxicity or to induce the regeneration of the damaged heart, the investigation is still at pre-clinical stages. Under a regenerative therapy hypothesis, MSCs are administered after an established dilated cardiomyopathy, whereas under a preventive therapy hypothesis, MSCs are transplanted before or during doxorubicin treatment (Table 1). It was reported that the local administration of BMMSCs after 4 weeks of doxorubicin treatment did not improve cardiac function [60]; however, when the BMMSC administration was performed 2 weeks after doxorubicin administration, it generated a significant improvement in LVEF [61]. In a rat model of dilated cardiomyopathy, the intravenous administration of BMMSCs 2 weeks after doxorubicin treatment only reduced myocardium fibrosis [62], but when 10 doses of BMMSCs (one per day) were given intravenously 10 weeks after the doxorubicin treatment, cardiac contractility was improved whereas myocardium fibrosis and LV diameter were reduced. These effects were associated with cardiac remodeling by the downregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [63]. The systemic administration of hUCBs after 2 weeks of doxorubicin treatment also reduced heart weight and cardiac fibrosis but without reported functional data [49]. Di and colleagues [64] reported that hUCBs significantly prevent cardiac dysfunction when they were administered intravenously during chemotherapy. Finally, when ASCs were administered before the doxorubicin chemotherapy, Oliveira and colleagues [65] reported a partial cardioprotective effect. According to the literature, the use of this kind of cell-based therapy is highly versatile because almost all therapies were successful (partial recovery or maintenance of cardiac function) given diverse factors, including (i) time and route of administration of MSCs, (ii) number of doses of MSCs, (iii) source of MSCs, and (iv) grade of cardiac injury induced by doxorubicin. Unfortunately, the duration of the beneficial effect induced by MSC administration has not been tested.

Doxorubicin also has a toxic effect in endogenous MSCs. Oliveira and colleagues [66] reported that BMMSCs, isolated from rats that received doxorubicin, have a lower proliferation rate and lower differentiation capacity (in comparison with cardiomyocytes), suggesting that autologous MSC transplantation to treat doxorubicin cardiomyopathy is not a suitable option for patients after doxorubicin treatment. Moreover, intravenous administration of allogeneic BMMSCs should be performed when plasmatic doxorubicin concentration is under 1 μM in order to reduce a direct cytotoxic effect [67].

The systemic administration of MSCs could have integral beneficial effects in patients with cancer. Zoja and colleagues [68] demonstrated that BMMSCs could preserve podocyte viability, reducing glomerular inflammation and sclerosis in an animal model of doxorubicin-induced nephropathy. Additionally, the inflammatory suppressive activity of MSCs could balance the inflammation induced by doxorubicin (i) in the brain, reducing TNF-α production by microglial cells [69], and (ii) in the liver, managing tissue-derived oxidative stress [70] (Fig. 1).

In regard to the use of MSC therapy to prevent or revert the cardiotoxicity effect of anti-cancer drugs such as daunomycin, idarubicin, mitoxantrone (anthracyclines), 5-fluorouracil (anti-metabolite), or cyclophosphamide (alkylating agent), we also expect a beneficial effect in cardiac function because these drugs have a common mechanism of toxicity in cardiomyocytes (excessive ROS production by mitochondria, leading to apoptosis), which is also described in doxorubicin toxicological studies [71–73].

Mesenchymal stem cell and cancer

It has been postulated that the regenerative potential of MSCs may be a negative feature in patients with cancer. In fact, there is a controversial point of view about the role of MSCs in cancer. Pre-clinical studies reported that MSCs could promote or inhibit tumor growth [74]. Many mechanisms have been associated with these opposite effects, such as vascular support, apoptosis modulation, chemokine signaling, and immune system modulation [36]. In experimental models of cancer in which doxorubicin is also present, the results about the role of MSCs are also contradictory. Human ASC-derived conditioned medium promoted the resistance of MDA-MB-231 cells to doxorubicin [75]; however, human ASCs inhibited the proliferation of MCF-7 cells in vitro [76] and increased the sensitivity of cells from a mammary tumor (SKBR3) to doxorubicin [77]. BMMSC-derived conditioned medium improved the viability of 4 T1 cells (mammary adenocarcinoma murine cells) in the presence of doxorubicin; likewise, when BMMSCs were co-injected with 4 T1 cells in the mammary fat pad of mice, BMMSCs inhibited drug-induced apoptosis of tumor cells [78]. However, when hUCBs were injected intravenously in a murine model of pre-established human colon carcinoma treated with doxorubicin, they did not alter drug-anti-tumoral efficiency [64]. On the other hand, MSCs have a positive chemotaxis for tumor cells but this property is independent of tumor growth capacity. Taking advantage of this propriety, many studies have proposed MSCs as a vehicle for delivery of anti-cancer drugs [79]. In summary, it seems that the final result (carcinogenic or anti-tumoral role of MSCs) depends on the microenvironment generated by the specific interaction between cancer cells and MSCs during tumor development (Fig. 1). Further investigation is needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of communication between MSCs with cancer cells and with immune system cells.

When human MSCs are properly ex vivo-expanded (that is, not forced to cell stress and non-exhausted), no tumoral transformation has been reported. Indeed, no association between autologous or allogeneic MSC administration and tumor formation was found in 36 clinical studies (phase I and II) reported by the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group [80]. However, Kudo-Saito [81], in a study of mice and humans with cancer metastasis, recently identified an MSC subpopulation that aggravates tumor progression, suggesting that MSCs could have a spontaneous tumorigenic potential in vivo. Thus, a longer follow-up is required to draw a final conclusion.

Conclusions

The quality of life of cancer survivors is an emergent topic in the scientific community for the consequences of the adverse events induced by chemotherapy. Therefore, doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity is still a relevant issue for oncologic treatment, particularly in pediatric patients. The use of cardiovascular disease therapies based on MSCs is safe, and the myocardium regeneration achieved has a promising impact on the recovery of cardiac function. In animal models, MSC administration could prevent myocardium injury induced by doxorubicin and regenerate the damaged tissue. In addition, owing to the pleiotropic effects of MSCs, their administration could have beneficial effects on extra-cardiac organs. However, in cancer applications, the use of MSCs is still controversial. More pre-clinical studies are needed to better predict the final outcome of the reciprocal influence of cancer cells and MSCs, which is dependent on the source and route of MSC administration and the state and grade of tumor growth. Additionally, clinical trials using MSC therapy may be considered in patients after surgical tumor removal, in order to prevent a heart vulnerability to cardiac diseases in cancer survivors.

Abbreviations

- ASC:

-

adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- BMMSC:

-

bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell

- CPC:

-

cardiac progenitor cell

- ESC:

-

embryonic stem cell

- hUCB:

-

mesenchymal stem cell derived from human umbilical cord blood

- IL:

-

interleukin

- iPSC:

-

induced pluripotent stem cell

- LV:

-

left ventricle

- LVEF:

-

left ventriclar ejection fraction

- MSC:

-

mesenchymal stem cell

- PGE2 :

-

prostaglandin E2

- ROS:

-

reactive oxygen species

- TLR4:

-

Toll-like receptor 4

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

References

Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:790–801. doi:10.1016/S1470-204570211-5.

Center M, Siegel R, Jemal A. Global cancer, facts & figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2011. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-027766.pdf.

Volkova M, Russell 3rd R. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: prevalence, pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2011;7:214–20.

Geiger S, Lange V, Suhl P, Heinemann V, Stemmler HJ. Anticancer therapy induced cardiotoxicity: review of the literature. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21:578–90. doi:10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283394624.

Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, Wasilewski K, Leisenring W, Armstrong GT, et al. Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1368–79. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn310.

Lipshultz SE, Cochran TR, Franco VI, Miller TL. Treatment-related cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:697–710. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.195.

Tacar O, Sriamornsak P, Dass CR. Doxorubicin: an update on anticancer molecular action, toxicity and novel drug delivery systems. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;65:157–70. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01567.x.

Patel KJ, Tredan O, Tannock IF. Distribution of the anticancer drugs doxorubicin, mitoxantrone and topotecan in tumors and normal tissues. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72:127–38. doi:10.1007/s00280-013-2176-z.

Takemura G, Fujiwara H. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy from the cardiotoxic mechanisms to management. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;49:330–52. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2006.10.002.

Fornari FA, Randolph JK, Yalowich JC, Ritke MK, Gewirtz DA. Interference by doxorubicin with DNA unwinding in MCF-7 breast tumor cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:649–56.

Franco VI, Henkel JM, Miller TL, Lipshultz SE. Cardiovascular effects in childhood cancer survivors treated with anthracyclines. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:134679. doi:10.4061/2011/134679.

Doroshow JH, Davies KJ. Redox cycling of anthracyclines by cardiac mitochondria. II. Formation of superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radical. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:3068–74.

Kim Y, Ma AG, Kitta K, Fitch SN, Ikeda T, Ihara Y, et al. Anthracycline-induced suppression of GATA-4 transcription factor: implication in the regulation of cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:368–77.

Huang C, Zhang X, Ramil JM, Rikka S, Kim L, Lee Y, et al. Juvenile exposure to anthracyclines impairs cardiac progenitor cell function and vascularization resulting in greater susceptibility to stress-induced myocardial injury in adult mice. Circulation. 2010;121:675–83. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.902221.

Piegari E, De Angelis A, Cappetta D, Russo R, Esposito G, Costantino S, et al. Doxorubicin induces senescence and impairs function of human cardiac progenitor cells. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:334. doi:10.1007/s00395-013-0334-4.

De Angelis A, Piegari E, Cappetta D, Marino L, Filippelli A, Berrino L, et al. Anthracycline cardiomyopathy is mediated by depletion of the cardiac stem cell pool and is rescued by restoration of progenitor cell function. Circulation. 2010;121:276–92. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.895771.

Hayashi T, Hirshman MF, Fujii N, Habinowski SA, Witters LA, Goodyear LJ. Metabolic stress and altered glucose transport: activation of AMP-activated protein kinase as a unifying coupling mechanism. Diabetes. 2000;49:527–31.

Liu J, Mao W, Ding B, Liang CS. ERKs/p53 signal transduction pathway is involved in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cells and cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1956–65. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2008.

Leung LK, Wang TT. Differential effects of chemotherapeutic agents on the Bcl-2/Bax apoptosis pathway in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;55:73–83.

Reed JC. Bcl-2 and the regulation of programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:1–6.

Guo RM, Xu WM, Lin JC, Mo LQ, Hua XX, Chen PX, et al. Activation of the p38 MAPK/NF-kappaB pathway contributes to doxorubicin-induced inflammation and cytotoxicity in H9c2 cardiac cells. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:603–8. doi:10.3892/mmr.2013.1554.

Kotamraju S, Konorev EA, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes is ameliorated by nitrone spin traps and ebselen. Role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33585–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003890200.

Marchant DJ, Boyd JH, Lin DC, Granville DJ, Garmaroudi FS, McManus BM. Inflammation in myocardial diseases. Circ Res. 2012;110:126–44. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243170.

Ma Y, Zhang X, Bao H, Mi S, Cai W, Yan H, et al. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 differentially regulate doxorubicin induced cardiomyopathy in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7, e40763. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040763.

Riad A, Bien S, Gratz M, Escher F, Westermann D, Heimesaat MM, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 deficiency attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in mice. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:233–43. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.01.004.

Jacoby JJ, Kalinowski A, Liu MG, Zhang SS, Gao Q, Chai GX, et al. Cardiomyocyte-restricted knockout of STAT3 results in higher sensitivity to inflammation, cardiac fibrosis, and heart failure with advanced age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12929–34. doi:10.1073/pnas.2134694100.

Delgado 3rd RM, Nawar MA, Zewail AM, Kar B, Vaughn WK, Wu KK, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor treatment improves left ventricular function and mortality in a murine model of doxorubicin-induced heart failure. Circulation. 2004;109:1428–33. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000121354.34067.48.

Isner JM, Ferrans VJ, Cohen SR, Witkind BG, Virmani R, Gottdiener JS, et al. Clinical and morphologic cardiac findings after anthracycline chemotherapy. Analysis of 64 patients studied at necropsy. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:1167–74.

Shakir DK, Rasul KI. Chemotherapy induced cardiomyopathy: pathogenesis, monitoring and management. J Clin Med Res. 2009;1:8–12. doi:10.4021/jocmr2009.02.1225.

Gillespie HS, McGann CJ, Wilson BD. Noninvasive diagnosis of chemotherapy related cardiotoxicity. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2011;7:234–44.

Ky B, Putt M, Sawaya H, French B, Januzzi Jr JL, Sebag IA, et al. Early increases in multiple biomarkers predict subsequent cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer treated with doxorubicin, taxanes, and trastuzumab. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:809–16. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.061.

Desai VG, CK J, Vijay V, Moland CL, Herman EH, Lee T, et al. Early biomarkers of doxorubicin-induced heart injury in a mouse model. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;281:221–9. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2014.10.006.

Mulrooney DA, Yeazel MW, Kawashima T, Mertens AC, Mitby P, Stovall M, et al. Cardiac outcomes in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: retrospective analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. BMJ. 2009;339:b4606. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4606.

Verma S, Dent S, Chow BJ, Rayson D, Safra T. Metastatic breast cancer: the role of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin after conventional anthracyclines. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:391–406. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.01.008.

Curran CF, Narang PK, Reynolds RD. Toxicity profile of dexrazoxane (Zinecard, ICRF-187, ADR-529, NSC-169780), a modulator of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Cancer Treat Rev. 1991;18:241–52.

Sieswerda E, van Dalen EC, Postma A, Cheuk DK, Caron HN, Kremer LC. Medical interventions for treating anthracycline-induced symptomatic and asymptomatic cardiotoxicity during and after treatment for childhood cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9, CD008011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008011.pub2.

Sanganalmath SK, Bolli R. Cell therapy for heart failure: a comprehensive overview of experimental and clinical studies, current challenges, and future directions. Circ Res. 2013;113:810–34. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300219.

Pfister O, Della Verde G, Liao R, Kuster GM. Regenerative therapy for cardiovascular disease. Transl Res. 2014;163:307–20. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2013.12.005.

Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024.

Mauritz C, Martens A, Rojas SV, Schnick T, Rathert C, Schecker N, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived Flk-1 progenitor cells engraft, differentiate, and improve heart function in a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2634–41. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr166.

Riggs JW, Barrilleaux BL, Varlakhanova N, Bush KM, Chan V, Knoepfler PS. Induced pluripotency and oncogenic transformation are related processes. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:37–50. doi:10.1089/scd.2012.0375.

Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–76.

Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, Morrone S, Chimenti S, Fiordaliso F, et al. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circ Res. 2004;95:911–21. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000147315.71699.51.

Barile L, Chimenti I, Gaetani R, Forte E, Miraldi F, Frati G, et al. Cardiac stem cells: isolation, expansion and experimental use for myocardial regeneration. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4:S9–S14. doi:10.1038/ncpcardio0738.

Bolli R, Chugh AR, D’Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, et al. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1847–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-673661590-0.

Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Thomson LE, Berman D, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (CADUCEUS): a prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:895–904. doi:10.1016/S0140-673660195-0.

Dixit P, Katare R. Challenges in identifying the best source of stem cells for cardiac regeneration therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:26. doi:10.1186/s13287-015-0010-8.

Kawada H, Fujita J, Kinjo K, Matsuzaki Y, Tsuma M, Miyatake H, et al. Nonhematopoietic mesenchymal stem cells can be mobilized and differentiate into cardiomyocytes after myocardial infarction. Blood. 2004;104:3581–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-04-1488.

Gopinath S, Vanamala SK, Gondi CS, Rao JS. Human umbilical cord blood derived stem cells repair doxorubicin-induced pathological cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;395:367–72. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.021.

Kang SK, Shin IS, Ko MS, Jo JY, Ra JC. Journey of mesenchymal stem cells for homing: strategies to enhance efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:342968. doi:10.1155/2012/342968.

Samper E, Diez-Juan A, Montero JA, Sepulveda P. Cardiac cell therapy: boosting mesenchymal stem cells effects. Stem Cell Rev. 2013;9:266–80. doi:10.1007/s12015-012-9353-z.

Ankrum J, Karp JM. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy: two steps forward, one step back. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:203–9. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2010.02.005.

Hatzistergos KE, Quevedo H, Oskouei BN, Hu Q, Feigenbaum GS, Margitich IS, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells stimulate cardiac stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Circ Res. 2010;107:913–22. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222703.

Loffredo FS, Steinhauser ML, Gannon J, Lee RT. Bone marrow-derived cell therapy stimulates endogenous cardiomyocyte progenitors and promotes cardiac repair. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:389–98. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.002.

Ryan JM, Barry FP, Murphy JM, Mahon BP. Mesenchymal stem cells avoid allogeneic rejection. J Inflamm (Lond). 2005;2:8. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-2-8.

van den Akker F, de Jager SC, Sluijter JP. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for cardiac inflammation: immunomodulatory properties and the influence of toll-like receptors. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:181020. doi:10.1155/2013/181020.

Liotta F, Angeli R, Cosmi L, Fili L, Manuelli C, Frosali F, et al. Toll-like receptors 3 and 4 are expressed by human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and can inhibit their T-cell modulatory activity by impairing Notch signaling. Stem Cells. 2008;26:279–89. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0454.

Liu H, McTaggart SJ, Johnson DW, Gobe GC. Original article anti-oxidant pathways are stimulated by mesenchymal stromal cells in renal repair after ischemic injury. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:162–72. doi:10.3109/14653249.2011.613927.

Secunda R, Vennila R, Mohanashankar AM, Rajasundari M, Jeswanth S, Surendran R. Isolation, expansion and characterisation of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord blood and matrix: a comparative study. Cytotechnology. 2014. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1007/s10616-014-9718-z.

Chen M, Fan ZC, Liu XJ, Deng JL, Zhang L, Rao L, et al. Effects of autologous stem cell transplantation on ventricular electrophysiology in doxorubicin-induced heart failure. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:576–82. doi:10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.03.002.

Garbade J, Dhein S, Lipinski C, Aupperle H, Arsalan M, Borger MA, et al. Bone marrow-derived stem cells attenuate impaired contractility and enhance capillary density in a rabbit model of doxorubicin-induced failing hearts. J Card Surg. 2009;24:591–9. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8191.2009.00844.x.

Mohammadi Gorji S, Karimpor Malekshah AA, Hashemi-Soteh MB, Rafiei A, Parivar K, Aghdami N. Effect of mesenchymal stem cells on doxorubicin-induced fibrosis. Cell J. 2012;14:142–51.

Yu Q, Li Q, Na R, Li X, Liu B, Meng L, et al. Impact of repeated intravenous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells infusion on myocardial collagen network remodeling in a rat model of doxorubicin-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;387:279–85. doi:10.1007/s11010-013-1894-1.

Di GH, Jiang S, Li FQ, Sun JZ, Wu CT, Hu X, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells mitigate chemotherapy-associated tissue injury in a pre-clinical mouse model. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:412–22. doi:10.3109/14653249.2011.646044.

Oliveira MS, Melo MB, Carvalho JL, Melo IM, Lavor MS, Gomes DA, et al. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and cardiac function improvement after stem cell therapy diagnosed by strain echocardiography. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2013;5:52–7. doi:10.4172/1948-5956.1000184.

Oliveira MS, Carvalho JL, Campos AC, Gomes DA, de Goes AM, Melo MM. Doxorubicin has in vivo toxicological effects on ex vivo cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Toxicol Lett. 2014;224:380–6. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.11.023.

Yang F, Chen H, Liu Y, Yin K, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Doxorubicin caused apoptosis of mesenchymal stem cells via p38, JNK and p53 pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;32:1072–82. doi:10.1159/000354507.

Zoja C, Garcia PB, Rota C, Conti S, Gagliardini E, Corna D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy promotes renal repair by limiting glomerular podocyte and progenitor cell dysfunction in adriamycin-induced nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F1370–81. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00057.2012.

Jansen CE, Dodd MJ, Miaskowski CA, Dowling GA, Kramer J. Preliminary results of a longitudinal study of changes in cognitive function in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Psychooncology. 2008;17:1189–95. doi:10.1002/pon.1342.

Tulubas F, Gurel A, Oran M, Topcu B, Caglar V, Uygur E. The protective effects of omega-3 fatty acids on doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in rats. Toxicol Ind Health. 2013. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1177/0748233713483203.

Focaccetti C, Bruno A, Magnani E, Bartolini D, Principi E, Dallaglio K, et al. Effects of 5-fluorouracil on morphology, cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy and ROS production in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2015;10, e0115686. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115686.

Adao R, de Keulenaer G, Leite-Moreira A, Bras-Silva C. Cardiotoxicity associated with cancer therapy: pathophysiology and prevention strategies. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013;32:395–409. doi:10.1016/j.repc.2012.11.002.

Levine ES, Friedman HS, Griffith OW, Colvin OM, Raynor JH, Lieberman M. Cardiac cell toxicity induced by 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide is modulated by glutathione. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1248–53.

Klopp AH, Gupta A, Spaeth E, Andreeff M, Marini 3rd F. Concise review: Dissecting a discrepancy in the literature: do mesenchymal stem cells support or suppress tumor growth? Stem Cells. 2011;29:11–9. doi:10.1002/stem.559.

Chen DR, Lu DY, Lin HY, Yeh WL. Mesenchymal stem cell-induced doxorubicin resistance in triple negative breast cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:532161. doi:10.1155/2014/532161.

Ryu H, Oh JE, Rhee KJ, Baik SK, Kim J, Kang SJ, et al. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured at high density express IFN-beta and suppress the growth of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2014;352:220–7. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2014.06.018.

Kucerova L, Skolekova S, Matuskova M, Bohac M, Kozovska Z. Altered features and increased chemosensitivity of human breast cancer cells mediated by adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:535. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-535.

Bergfeld SA, Blavier L, DeClerck YA. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells promote survival and drug resistance in tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:962–75. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0400.

Gjorgieva D, Zaidman N, Bosnakovski D. Mesenchymal stem cells for anti-cancer drug delivery. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2013;8:310–8.

Lalu MM, McIntyre L, Pugliese C, Fergusson D, Winston BW, Marshall JC, et al. Safety of cell therapy with mesenchymal stromal cells (SafeCell): a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. PLoS One. 2012;7, e47559. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047559.

Kudo-Saito C. Cancer-associated mesenchymal stem cells aggravate tumor progression. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3:23. doi:10.3389/fcell.2015.00023.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a FONDECYT 1130470 grant to FE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in designing, drafting, and critically revising the manuscript and read and approved the final version.

Authors’ information

FE, PhD, is a professor at the Center for Regenerative Medicine, Facultad de Medicina, Clínica Alemana-Universidad del Desarrollo. He has investigation experience in MSC therapy for type 1 diabetes mellitus and its main complications and has made important contributions in both topics. He was involved in the development of a cardioprotective cell-based treatment for doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. JG, PhD, is a professor at the Faculty of Health Science, Universidad San Sebastián, Santiago, Chile. His research topics are related to the mechanisms of skeletal muscle regeneration and cardiac remodeling and stem cell therapy in several animal models. ME, PhD, is a professor at the Center for Regenerative Medicine, Facultad de Medicina, Clínica Alemana-Universidad del Desarrollo. His studies are based on the mechanisms of anti-inflammation, regeneration, and anti-fibrosis induced by MSC administration in diabetic nephropathy, diabetic cardiomyopathy, and liver steatosis. CC, MD, is from the Cancer Care Center Fundación Arturo López Pérez and is a specialist in oncology. He usually uses anthracyclines in his cancer therapies and also supervises several clinical trials using new anti-neoplastic drugs. HCS, MD, PhD, is a full professor of physiology at the Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. He is a specialist in cardiovascular physiology and works with hypertension and heart failure models. Lately, he has been working with MSCs and myocardial infarction in rats. SDC, PhD, is a professor at the Center for Regenerative Medicine, Facultad de Medicina, Clínica Alemana-Universidad del Desarrollo. He investigates MSC-based therapies for cardiac diseases (diabetic and doxorubicin cardiomyopathy) at the pre-clinical level. He also studies the effect of MSC derivatives as therapeutic agents for doxorubicin cardiomyopathy.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ezquer, F., Gutiérrez, J., Ezquer, M. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for doxorubicin cardiomyopathy: hopes and fears. Stem Cell Res Ther 6, 116 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-015-0109-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-015-0109-y