Abstract

Background

Adolescents living with chronic illnesses engage in health risk behaviors (HRB) which pose challenges for optimizing care and management of their ill health. Frequent monitoring of HRB is recommended, however little is known about which are the most useful tools to detect HRB among chronically ill adolescents.

Aims

This systematic review was conducted to address important knowledge gaps on the assessment of HRB among chronically ill adolescents. Its specific aims were to: identify HRB assessment tools, the geographical location of the studies, their means of administration, the psychometric properties of the tools and the commonest forms of HRB assessed among adolescents living with chronic illnesses globally.

Methods

We searched in four bibliographic databases of PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts for empirical studies published until April 2017 on HRB among chronically ill adolescents aged 10–17 years.

Results

This review indicates a major dearth of research on HRB among chronically ill adolescents especially in low income settings. The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System and Health Behavior in School-aged Children were the commonest HRB assessment tools. Only 21% of the eligible studies reported psychometric properties of the HRB tools or items. Internal consistency was good and varied from 0.73 to 0.98 whereas test–retest reliability varied from unacceptable (0.58) to good (0.85). Numerous methods of tool administration were also identified. Alcohol, tobacco and other drug use and physical inactivity are the commonest forms of HRB assessed.

Conclusion

Evidence on the suitability of the majority of the HRB assessment tools has so far been documented in high income settings where most of them have been developed. The utility of such tools in low resource settings is often hampered by the cultural and contextual variations across regions. The psychometric qualities were good but only reported in a minority of studies from high income settings. This result points to the need for more resources and capacity building for tool adaptation and validation, so as to enhance research on HRB among chronically ill adolescents in low resource settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Research focusing on health risk behaviors (HRB) among adolescents living with chronic illness has increased over the past few decades. HRB are defined as specific forms of behavior associated with increased susceptibility to a specific disease or ill health on the basis of epidemiological or social data [1]. Examples of HRB include: alcohol, tobacco and drug use, unhealthy dietary habits, sexual behaviors contributing to unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, behavior that contributes to unintentional injury or violence, and inadequate physical activity [2, 3]. In the past, it was presumed that chronically ill adolescents are restricted by their ill health from engaging in HRB [4, 5]. However, a growing body of evidence shows that chronically ill adolescents engage in such behavior at rates equivalent to [6,7,8] or at times higher [9,10,11,12] than their healthy peers. Some studies for example report higher frequency of cigarette smoking among adolescents with asthma [13, 14] and more substance or drug use among adolescents with mental illnesses [9, 15] compared to their healthy peers. In addition, chronically ill adolescents are often victims of behaviors resulting in unintentional injury and violence, such as bullying and sexual assault [16, 17]. Other problematic forms of HRB among chronically ill adolescents include; inadequate physical activity [18,19,20], risky sexual behavior [10, 11], and poor dietary habits [21].

Engagement in HRB is problematic for chronically ill adolescents because it hinders optimal care and management of ill health [22]. For example, studies among young people living with HIV report that anti-retroviral therapy adherence rates are poorer among the patients with riskier health lifestyle as compared to their HIV infected peers who have healthier lifestyles [23, 24]. Similarly, engagement in HRB such as tobacco use, recreational drugs use, and risky sexual behavior has been shown to hamper proper management of type 1 diabetes [25], asthma [26], and mental illness [27] among adolescents. Poor disease management compounded by direct adverse effects resulting from engagement in HRB, most likely translates into poorer health outcomes among chronically ill adolescents [5, 28]. Thus, promotion and maintenance of healthier behavioral practices early in adolescence has great potential to enhance positive long-term health outcomes for these patients [23].

Regarding the public health burden posed by HRB, frequent monitoring of such behaviors is recommended for supporting clinical and preventive efforts directed at improving lives of young people with chronic illnesses and their families [5, 29]. Although there are numerous measures of HRB, evidence is still meagre on the most frequently utilized HRB measures as well as the psychometric properties of HRB tools among chronically ill adolescents in various geographical contexts. Moreover, without proper adaptation, measurement bias and compromise to various psychometric properties like validity and reliability may arise [30, 31]. Bias also arises from unfamiliar content of the tests, translation challenges and unfamiliar means of tool administration [30]. Studies have similarly shown that variations in how questions are administered and how respondents are contacted affects the accuracy and quality of data collected [32]. There is still a lack of knowledge concerning the major forms of HRB, their commonly utilized assessment tools, their psychometric properties and their methods of administration in studies among chronically ill adolescents.

We therefore carried out this review to determine the current gaps in knowledge about tools to measure HRB. The review synthesizes findings from empirical studies conducted globally among adolescents living with chronic illnesses so as to: (i) identify the commonly utilized HRB assessment tools or sources of items used; (ii) describe the geographical utility of HRB assessments tools; (iii) identify the common means of HRB tool administration; (iv) document the reported adaptation and psychometric properties of HRB assessment tools or items; and (v) summarize the commonly assessed forms of HRB. We expect the results of this systematic review to aid HRB tool adaptation and validation procedures as well as enhance planning of research and interventions targeting adolescents living with chronic illnesses especially in low and middle income settings.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following recommended guidelines for conducting systematic reviews [33]. We searched for relevant literature in four bibliographic databases: PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts. The search was initially conducted between November and December 31, 2015 and later updated in May 2017. The search strategy was formulated by two reviewers (DS and AA) and comprised of the following non-MeSH terms combined with Boolean operators: risk behavior OR risk taking OR health behavior OR healthy lifestyle AND adolescents OR Youth OR Teens AND Chronic condition OR Chronic disease OR Chronic illness. Additionally, other relevant studies were identified by searching the reference lists of the retrieved articles.

In this review, our study inclusion criteria were: (i) empirical studies published in a peer reviewed journal from January 1, 1980 to April 30, 2017; (ii) studies with participants aged 10–17 years or with mean age within this age bracket; and (iii) studies assessing for both HRB and chronic illness among the same study participants. The chronic conditions considered are those documented by the United States Department of Health and Human Services for the standard classification scheme [34]. Only studies published in English were included in this review. Studies were excluded if: (i) they were non-empirical (such as reviews, commentaries, letters to editor, conference abstracts), (ii) their participants had an age range or mean age below or above the 10–17 years’ category and (iii) they assessed only HRB without consideration of chronic illness or vise-versa.

Data extraction was done by two independent reviewers (DS, MKN). The data was extracted to Microsoft Excel spread sheets with the following details from eligible studies: author and date of publication, country where the study was conducted, age of the participants (mean age), form of chronic illness, assessment tool or source of items on HRB, methods of administration of HRB measures, psychometric properties of the tool (if documented), and form of HRB assessed were extracted. For reliability, we extracted measures of internal consistency, and interrater reliability such as the Cronbach’s alpha, intra-class coefficient (ICC) and coefficient of correlation whenever reported. For tool validity, we extracted construct, criterion, divergent or convergent validities whenever reported. We also noted any aspects of tool adaptation such as cultural adaptation, content validity, forward-back translations in case they were reported (refer to Table 4).

Data analysis involved collating and summarizing of results. The synthesis of data extracted from the eligible studies was done narratively. Frequencies and/or percentages were computed in Microsoft Excel program so as to summarize the findings on: the frequency of the various HRB tools/measures reported in studies, geographical utilization of these tools, forms of HRB assessed, methods of HRB tool/item administration and the various chronic conditions reported. Due to the high variation in HRB tools or items used, the tools were classified into four categories namely: (i) full version HRB assessment tools; (ii) modified version of HRB assessment tools; (iii) borrowed items on HRB; and (iv) items on HRB either newly developed or whose source is not specified by the author. Also in situations where more than one eligible manuscript was written using data from the same study, frequencies on HRB tools were collated in order to represent a single frequency count for this reported HRB assessment tool. For purposes of data management the reported chronic conditions were re-categorized into: respiratory, cardio-vascular, metabolic, hematological, mental, musculoskeletal, neurologic, dermatologic, digestive, physical disability and HIV.

Results

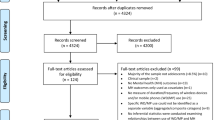

The literature search yielded a total of 1623 articles and following a systematic appraisal of this literature (refer to Fig. 1), a total of 79 full articles were eligible for inclusion in this review.

Majority of the eligible studies were conducted in North America (60%) and Europe (24%). The rest of them were from Asia (8%), South America (2%), Oceania (2%) and a few were multi-site studies conducted in both Europe and North America (2%). The study site of one eligible study was not reported in the article [35].

Results of the most frequently utilized HRB tools/items are shown in Table 1. Briefly, from a total of 37 full version HRB tools, 7 tools namely: Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC), Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS), Swiss Multi-centric Adolescent Survey on Health (SMASH), car, relax, alone, forget, friends, trouble (CRAFT) substance Abuse Screening Test, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) and Life and Health in Youth questionnaire were the most commonly utilized. The items on HRB in 12 of the studies from this review were either newly developed or their sources were not specified [23, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

The HBSC tool is a self-completion questionnaire administered in class room settings to adolescents aged 11–15 years and the HBSC study is conducted every 4 years across 44 countries in Europe and North America since its inception in 1982 [3]. The key health behaviors captured by this tool include; bullying and fighting, oral hygiene, physical activity and sedentary behavior, sexual behavior, substance use (e.g. alcohol, tobacco and cannabis), weight reduction behavior, behaviors resulting in injury, and dietary habits [3]. The YRBS tool (Standard and National High School questionnaires) is developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to monitor HRB that are considered leading causes of disability, death and social problems among youths in 9th to 12th grade (approximately 14–18 years) in the US Students complete the self-administered questionnaire during one class period and record their responses directly in an answer sheet. This tool assesses 6 forms of HRB: sexual risk behaviors, tobacco use, alcohol and other drug use, inadequate physical activity and unhealthy dietary behaviors [2].

Results on the most frequently assessed forms of HRB are summarized in Table 2. Overall, alcohol, tobacco and other drug use and physical inactivity were the most frequently assessed forms of HRB.

The HRB tool/item administration (Table 3), adolescent self-completed paper and pencil format, face-to-face interview with the adolescent, and Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview (ACASI) were the most frequently utilized means.

Adaptation or psychometric properties of the HRB tools or items among the study population were only reported in 17 studies moreover. Most of these (82%) were conducted in the USA (see Table 4). Five of these studies reported aspects of adaptation such as forward-back translations, content validity, item completeness, and cultural appropriateness but without reporting any psychometric data [44, 47,48,49,50]. Among those that reported psychometric data, only 6 studies [9, 18, 51,52,53,54] reported this data for an entire HRB tool or entire tool from which HRB items were borrowed while the rest reported only data for select items from the HRB tool. Psychometric data for the whole HRB tool was reported for the following instruments: Kriska’s Modifiable Activity questionnaire; Modified Self Report of Delinquency; Risk Behavior and Risk Scale; Delinquency Scale; and the Denys Self-Care Practice instrument. Moreover, psychometric properties of Youth Self Report; Child Behavior Check List; and the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV in the context of HRB evaluation were also reported. The reported psychometric properties of these tools satisfied the recommended thresholds for psychometric rigor for example the internal consistency (coefficients ranged from 0.73 to 0.98) and test–retest reliability (coefficients ranged from 0.58 to 0.85). The psychometric data reported on selected HRB items were mainly for items assessing physical activity or sedentary behavior [38, 55] and these also had good test–retest reliability ranging from 0.8 to 0.81 and good internal consistency of 0.73.

The HRB tools were largely used among adolescents with the chronic conditions of mental illness, especially depression (21.4%), respiratory conditions such as asthma and cystic fibrosis (13.8%), metabolic conditions such as diabetes (9.4%) and neurological conditions such as autism spectrum disorders, epilepsy and cerebral palsy (6.9%). To a lesser extent, the HRB tools were also utilized among adolescent patients with musculoskeletal conditions such as arthritis, cardio vascular conditions (e.g. congenital heart disease and hypertension), HIV, cancer, digestive tract conditions (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease and gastritis), disabling conditions (e.g. visual, speech and hearing problems) and dermatological conditions such as atopic dermatitis and eczema. The detailed summary of eligible studies is presented in Table 4.

Discussion

This review identified the commonly utilized HRB assessment tools or sources of items used; describing the geographical utility of HRB assessments tools, the common methods of HRB tool administration, the adaptation and psychometric properties; and providing a summary of the forms of HRB commonly assessed. Our findings show that the YRBS and HBSC are the most frequently used tools to assess HRB or sources of items on HRB. This may partly be explained by their high level of comprehensiveness in assessing priority and multiple forms of HRB thereby being useful in many contexts. While both tools assess for HRB among adolescents, the YRBSS targets an older adolescent age group compared to the HBSC. The HBSC however focuses more on the social and environmental context for HRB such as influence of peers, school environment, and family characteristics. The YRBSS explores HRB in greater detail compared to the HBSC although the former lacks items on oral hygiene, health complaints and chronic illnesses. Besides the YRBSS and HBSC, a wide range of other HRB tools have been utilized, and some of them assess the same form of HRB but in a different format. One challenge that this may present is the lack of uniformity or standardized formats to compare similar HRB outcomes across different study populations.

Findings from this review also indicate that research on HRB among adolescents living with chronic illnesses in low and middle income countries (LMIC) is still limited. This is unfortunate since the majority of the adolescent population lives in LMICs [56] where a disproportionately higher burden of HRB occurrence is also reported [57]. There are three potential reasons that may explain the limited research on HRB among chronically ill adolescents in LMICs. First there is limited research that explicitly focuses on the adolescent age-group [5]. Second, research on this topic is not adequately prioritized [4]. Nonetheless, research on HRB among chronically ill adolescents has significantly grown over the past two decades [4, 5] though with disproportionately lower prioritization especially in LMICs. The third reason is the scarcity of standardized measures on various health outcomes among chronically ill adolescents [5]. The need for more investment in research on health and behavioral outcomes among chronically ill adolescents especially in LMICs cannot be overemphasized given that the burden of chronic diseases is increasing in such settings [58].

The use of appropriate and psychometrically sound instruments is essential for having good insight in adolescents’ behavior so as to be able to address certain forms of behavior that could be dangerous either for the patients themselves or for others. However, our findings indicate that HRB tool adaptation and psychometric properties are rarely reported among studies on HRB of chronically ill adolescents. Partly, this could be due to the fact that the majority of the studies were conducted in the western context where the majority of these tools have been developed. To indicate the adaptation and psychometric properties, some of the authors simply cited studies where similar HRB tools or items have been previously utilized [59,60,61]. This may not guarantee validity and reliability for a number of reasons. First, some of the tools were previously adapted and validated for use among adolescents without chronic conditions and thus we cannot ascertain if they retain their good psychometric properties when used among chronically ill adolescents. Secondly, some of the original validation or adaptation may have taken place more than two decades back and considering the evolution of HRB, various behavioral constructs used in these tools may no longer be appropriate. Another observation is that many researchers borrow specific items from previously well validated or standardized HRB tools but without checking the item specific psychometric properties. Our findings also reveal that there is a tendency for researchers to perform the adaptation processes such as forward-back translation and content review for item completeness, clarity or cultural appropriateness; without performing psychometric evaluations. It should be emphasized that much as adaptation is an important process, psychometric evaluation is equally critical for ascertaining item reliability and validity. Without adequate adaptation and psychometric evaluation we cannot ascertain if the scales and items retain their good psychometric properties following the modifications made. Overcoming such challenges requires a mixed methods approach for tool adaptation and validation [31, 62, 63]. For instance, a four step approach has been suggested as adequate for adapting tools in low and middle income countries [64]. The four step approach suggested for LMICs entails: (i) construct definition which can be done through review of literature, and consultation with community or local professionals in order to achieve conceptual clarity and equivalence; (ii) item pool creation which involves preparation of a list of potentially acceptable items in a clear and unambiguous language using feedback from the first step; (iii) developing clear guidelines for administration of the items to ensure operational equivalence; (iv) test evaluation which involves psychometric evaluation to assess measurement and functional equivalence [64].

Additionally, findings from this review indicate that there are numerous methods of HRB tool or item administration. Self-administered paper and pencil format was the most popular method and this could have been because of the participants’ good level of literacy given that majority of them were school attending adolescents. This method of administration is also preferred as it is associated with a high level of privacy and ease of administration [32]. On the contrary, its disadvantage arises from its requirement for some literacy levels among the respondents as well as the cognitive burden that respondents face in comprehending and recalling their experiences [32, 65]. Face-to-face interviews were also frequently utilized in assessing HRB. This method is linked to high response rates and the benefit of probing participants and clarifying unclear questions [65]. Nonetheless, face-to-face interviews are hampered by the lack of anonymity which may result to social desirability bias and impression management [32, 65]. Similar to findings from other studies [32, 66], our review shows that there is growing utilization of electronic methods of HRB tool and item administration. Electronic methods [such as the Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview (ACASI), telephone and internet based surveys] are valued for their high level of privacy or anonymity [32, 65] and some of them such as the ACASI have been further designed to benefit people with low literacy levels [65]. However, electronic methods require access to electronic devices and services (such as telephone, computer, and internet), may require greater auditory demands and some demand a high level of literacy [32, 66]. The presence of numerous HRB tool administration methods presents a wide set of options which can be tailored to suit contextual factors, research skills, resource availability and specific needs of study populations. However, researchers should carefully think through the dynamics surrounding tool administration and data collection procedures in order to identify the most appropriate methods to ensure that high quality data is collected.

Furthermore, our findings show that alcohol, tobacco, drug use behavior and physical inactivity are the most frequently researched HRB among adolescents with chronic conditions. Substance use among chronically ill adolescents is of major concern and many studies report higher or equivalent rates of substance use (e.g. cannabis, tobacco, illicit drugs) among these adolescents in comparison to their healthy peers [12, 13, 67]. This may explain why most of HRB research among this group focuses on substance use behavior. Our findings also indicate that physical inactivity and sexual risk behavior are frequently assessed. Growing research interest on sexuality of chronically ill adolescents indicates that sexual risk behavior is a concern [7, 10,11,12] and this dissents the earlier notion that they are less sexually active than their healthy peers [4]. Likewise, physical activity among adolescents with chronic conditions is gaining measureable research interest [28]. This may surround its vital role in appropriate management of chronic illness such as: cardio-respiratory fitness among asthmatic patients and optimization of quality of life among patients with cerebral palsy [28]. Our results also indicate that violence related behaviors are frequently investigated among chronically ill adolescents. Adolescents with chronic illnesses often fall victim of violence such as bullying, assault and forced sexual encounters [17, 50]; and thus raising the need for increased research on this matter. On the other hand, our findings show that poor hygiene, inadequate sleep and behavior resulting to unintentional injury were the least frequently assessed forms of HRB in this review. This may be due to the reality that most of these problematic behaviors are of greater research interest in LMICs (whose representation is still low) where their occurrence is documented to be greater, compared to high income settings [57, 68]. Our findings on the variation in the frequency of the forms of HRB assessed, may partly imply that there is some tendency to measure HRB in isolation. However, co-occurrence of different adolescent HRB is increasingly documented [69, 70], and therefore different forms of HRB should be assessed concurrently.

Our review draws its major strengths from the utilization of a rigorous methodological framework [33] and also its specific focus on the adolescent age-group in a global perspective. However, we did not appraise the quality of the studies included in our systematic review. Nonetheless, given that our study objectives aimed at describing extent of utilization of HRB tools and providing an over-view of various forms of HRB assessed, we do not expect any major issues arising from the quality of studies to influence our findings.

Conclusion

Overall, most research on health risk behavior among chronically ill adolescents emanates from high income settings such as Europe and North America where the majority of the HRB assessment tools have also been developed. Therefore more investment is needed in research on health and behavioral outcomes among chronically ill adolescents especially in LMICs. Although the YRBSS and HBSC are utilized most, a variety of other HRB tools are used as well, however without documentation of adaptation and psychometric qualities. This poses challenges for researchers and practitioners who are keen to evaluate HRB in LMICs. We recommend the use of the mixed methods approach for tool adaptation and validation, which involves both qualitative approaches (e.g. focus group discussions and in-depth interviews) and quantitative approaches (e.g. psychometric testing) to develop and standardize measures for use by health researchers especially from LMICs. In the industrialized setting, we recommend the use of YRBSS or HBSC owing to their comprehensive approach to assessing multiple forms of HRB. The results of more research on HRB among chronically ill adolescents could translate to significant clinical, public health and social economic benefits, especially for adolescents living with such illnesses and their families.

Abbreviations

- ACASI:

-

Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test

- CAPI:

-

Computer Assisted Personal Interview

- CRAFT:

-

car, relax, alone, forget, friends, trouble

- HBSC:

-

Health Behavior in School-aged Children

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- HRB:

-

health risk behavior

- LMIC:

-

low and middle income countries

- SMASH:

-

Swiss Multi-centric Adolescent Survey on Health

- YRBSS:

-

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

References

DiClemente RJ, Hansen WB, Ponton LE. Handbook of adolescent health risk behavior. Berlin: Springer; 2013.

CDC. Adolescent and school health. Atlanta, USA. 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/overview.htm. Accessed 14 Nov 2015.

Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2009/2010 survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2012.

Valencia LS, Cromer BA. Sexual activity and other high-risk behaviors in adolescents with chronic illness: a review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2000;13(2):53–64.

Sawyer SM, Drew S, Yeo MS, Britto MT. Adolescents with a chronic condition: challenges living, challenges treating. Lancet. 2007;369(9571):1481–9.

Scaramuzza A, De Palma A, Mameli C, Spiri D, Santoro L, Zuccotti G. Adolescents with type 1 diabetes and risky behaviour. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(8):1237–41.

Suris JC, Resnick MD, Cassuto N, Blum RW. Sexual behavior of adolescents with chronic disease and disability. J Adolesc Health. 1996;19(2):124–31.

Jones SE, Merkle SL, Fulton JE, Wheeler LS, Mannino DM. Relationship between asthma, overweight, and physical activity among US high school students. J Community Health. 2006;31(6):469–78.

Wilens TE, Martelon M, Joshi G, Bateman C, Fried R, Petty C, et al. Does ADHD predict substance-use disorders? A 10-year follow-up study of young adults with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(6):543–53.

Choquet M, Fediaevsky LDP, Manfredi R. Sexual behavior among adolescents reporting chronic conditions: a French national survey. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20(1):62–7.

Suris JC, Parera N. Sex, drugs and chronic illness: health behaviours among chronically ill youth. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15(5):484–8.

Simpson K, Janssen I, Boyce WF, Pickett W. Risk taking and recurrent health symptoms in Canadian adolescents. Prev Med. 2006;43(1):46–51.

Rhee H, Hollen PJ, Sutherland M, Rakes G. A pilot study of decision-making quality and risk behaviors in rural adolescents with asthma. Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol. 2007;20(2):93–104.

Jones SE, Merkle S, Wheeler L, Mannino DM, Crossett L. Tobacco and other drug use among high school students with asthma. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):291–4.

Katon W, Richardson L, Russo J, McCarty CA, Rockhill C, McCauley E, et al. Depressive symptoms in adolescence: the association with multiple health risk behaviors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(3):233–9.

Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. The associations between victimization, feeling unsafe, and asthma episodes among US high-school students. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):802–4.

Alriksson-Schmidt AI, Armour BS, Thibadeau JK. Are adolescent girls with a physical disability at increased risk for sexual violence? J Sch Health. 2010;80(7):361–7.

Nixon PA, Orenstein DM, Kelsey SF. Habitual physical activity in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(1):30–5.

Barbiero SM, D’Azevedo Sica C, Schuh DS, Cesa CC, de Oliveira Petkowicz R, Pellanda LC. Overweight and obesity in children with congenital heart disease: combination of risks for the future? BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:271.

Jones SE, Lollar DJ. Relationship between physical disabilities or long-term health problems and health risk behaviors or conditions among US high school students. J Sch Health. 2008;78(5):252–7.

Park S, Blanck HM, Sherry B, Jones SE, Pan L. Regular-soda intake independent of weight status is associated with asthma among US high school students. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1):106–11.

Suris JC, Michaud PA, Viner R. The adolescent with a chronic condition. Part I: developmental issues. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(10):938–42.

Lagrange RD, Mitchell SJ, Lewis M, Abramowitz S, D’Angelo LJ. Health protective behaviors among young people living with HIV/AIDS. J AIDS Clin Res. 2012;S1(13):7348.

Mellins CA, Tassiopoulos K, Malee K, Moscicki A-B, Patton D, Smith R, et al. Behavioral health risks in perinatally HIV-exposed youth: co-occurrence of sexual and drug use behavior, mental health problems, and nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(7):413–22.

Silverstein J, Klingensmith G, Copeland K, Plotnick L, Kaufman F, Laffel L, et al. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes a statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(1):186–212.

Towns SJ, Van Asperen PP. Diagnosis and management of asthma in adolescents. Clin Respir J. 2009;3(2):69–76.

Hawkins EH. A tale of two systems: co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders treatment for adolescents. Ann Rev Physiol. 2009;60:197–227.

Riner WF, Sellhorst SH. Physical activity and exercise in children with chronic health conditions. J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2(1):12–20.

Suris JC, Michaud PA, Akre C, Sawyer SM. Health risk behaviors in adolescents with chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):e1113–8.

van de Vijver FJR. Bias and equivalence: Cross-cultural perspectives. In: Harkness JA, Mohler P, van de Vijver FJR, editors. Cross-cultural survey methods. New Jersey: Wiley-Interscience; 2003. p. 143–55.

Abubakar A. Equivalence and transfer problems in cross-cultural research. In: Wright JD, editor. International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2015. p. 929–33.

Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. Am J Public Health. 2005;27(3):281–91.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Goodman R, Posner S, Huang E, Parekh A, Koh H. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E66.

Gold MA, Gladstein J. Substance use among adolescents with diabetes mellitus: preliminary findings. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14(2):80–4.

Kyngas HA. Predictors of good adherence of adolescents with diabetes (insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus). Chronic Illn. 2007;3(1):20–8.

Tortolero SR, Peskin MF, Baumler ER, Cuccaro PM, Elliott MN, Davies SL, et al. Daily violent video game playing and depression in preadolescent youth. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(9):609–15.

Schmitz KH, Lytle LA, Phillips GA, Murray DM, Birnbaum AS, Kubik MY. Psychosocial correlates of physical activity and sedentary leisure habits in young adolescents: the teens eating for energy and nutrition at school study. Prev Med. 2002;34(2):266–78.

Shrier LA, Harris SK, Sternberg M, Beardslee WR. Associations of depression, self-esteem, and substance use with sexual risk among adolescents. Prev Med. 2001;33(3):179–89.

Blum RW, Kelly A, Ireland M. Health-risk behaviors and protective factors among adolescents with mobility impairments and learning and emotional disabilities. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(6):481–90.

Bush T, Richardson L, Katon W, Russo J, Lozano P, McCauley E, et al. Anxiety and depressive disorders are associated with smoking in adolescents with asthma. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):425–32.

Uzark K, VonBargen-Mazza P, Messiter E. Health education needs of adolescents with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Health Care. 1989;3(3):137–43.

Kunz JH, Greenley RN, Mussatto KA, Roth-Wojcicki B, Miller T, Freeman ME, et al. Personal attitudes, perceived social norms, and health-risk behavior among female adolescents with chronic medical conditions. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(7):877–86.

Warren CM, Dyer AA, Otto AK, Smith BM, Kauke K, Dinakar C, et al. Food allergy—related risk-taking and management behaviors among adolescents and young adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(2):381–90.

Wilcox HC, Rains M, Belcher H, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, Lee R, et al. Behavioral problems and service utilization in children with chronic illnesses referred for trauma-related mental health services. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016;37(1):62–70.

Kline-Simon AHMS, Weisner CDMSW, Sterling SDMSW. Point prevalence of co-occurring behavioral health conditions and associated chronic disease burden among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(5):408.

Brooks TL, Harris SK, Thrall JS, Woods ER. Association of adolescent risk behaviors with mental health symptoms in high school students. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(3):240–6.

Asnani MR, Bhatt K, Younger N, McFarlane S, Francis D, Gordon-Strachan G, et al. Risky behaviours of Jamaican adolescents with sickle cell disease. Hematol J. 2014;19(7):373–9.

AlBuhairan FS, Tamim H, Al Dubayee M, Aldhukair S, Al Shehri S, Tamimi W, et al. Time for an adolescent health surveillance system in saudi arabia: findings from “jeeluna”. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(3):263–9.

Sentenac M, Gavin A, Gabhainn SN, Molcho M, Due P, Ravens-Sieberer U, et al. Peer victimization and subjective health among students reporting disability or chronic illness in 11 Western countries. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(3):421–6.

Woods SB, Farineau HM, McWey LM. Physical health, mental health, and behaviour problems among early adolescents in foster care. Child. 2013;39(2):220–7.

Frey M. Behavioral correlates of health and illness in youths with chronic illness. Appl Nurs Res. 1996;9(4):167–76.

Frey MA, Guthrie B, Loveland-Cherry C, Park PS, Foster CM. Risky behavior and risk in adolescents with IDDM. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20(1):38–45.

Frazer AL, Rubens S, Johnson-motoyama M, Dipierro M, Fite PJ. Acculturation dissonance, acculturation strategy, depressive symptoms, and delinquency in Latina/o adolescents. Child Youth Care Forum. 2017;46(1):19–33.

Elder JP, Broyles SL, Brennan JJ, Zuniga de Nuncio ML, Nader PR. Acculturation, parent-child acculturation differential, and chronic disease risk factors in a Mexican-American population. J Immigr Health. 2005;7(1):1–9.

United Nations. World population monitoring: adolescents and youth. A concise report. New York; 2012. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/theme/adolescents-youth/index.shtml. Accessed 14 Feb 2016.

Ruiz-Casares M. Unintentional childhood injuries in sub-Saharan Africa: an overview of risk and protective factors. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(4A):51–67.

Boutayeb A, Boutayeb S. The burden of non communicable diseases in developing countries. Int J Equity Health. 2005;4(1):2.

Britto MT, Garrett JM, Dugliss MAJ, Daeschner CW Jr, Johnson CA, Leigh MW, et al. Risky behavior in teens with cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease: a multicenter study. Pediatrics. 1998;101(2):250–6.

Lunt D, Briffa T, Briffa NK, Ramsay J. Physical activity levels of adolescents with congenital heart disease. Aust J Physiother. 2003;49(1):43–50.

Nylander C, Fernell E, Tindberg Y. Chronic conditions and coexisting ADHD-a complicated combination in adolescents. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(9):1209–15.

Harachi TW, Choi Y, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Bliesner SL. Examining equivalence of concepts and measures in diverse samples. Prev Sci. 2006;7(4):359–68.

Abubakar A, Dimitrova R, Adams B, Jordanov V, Stefenel D. Procedures for translating and evaluating equivalence of questionnaires for use in cross-cultural studies. Bull Transilv Univ Braşov Ser VII Soc Sci Law. 2013;6:55.

Holding P, Abubakar A, Wekulo P. Where there are no tests: a systematic approach to test adaptation. In: Landow ML, editor. Cognitive Impairment: causes, diagnosis and treatment. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. p. 189–200.

Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(2):104–23.

Vereecken CA, Maes L. Comparison of a computer-administered and paper-and-pencil-administered questionnaire on health and lifestyle behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(4):426–32.

Erickson JD, Patterson JM, Wall M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Risk behaviors and emotional well-being in youth with chronic health conditions. Child Health Care. 2005;34(3):181–92.

Prüss-Ustün A, Bartram J, Clasen T, Colford JM, Cumming O, Curtis V, et al. Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low-and middle-income settings: a retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(8):894–905.

Hale DR, Viner RM. The correlates and course of multiple health risk behaviour in adolescence. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):458.

de Winter AF, Visser L, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WA, Reijneveld SA. Longitudinal patterns and predictors of multiple health risk behaviors among adolescents: the TRAILS study. Prev Med. 2016;84:76–82.

Holmberg K, Hjern A. Bullying and attention-deficit—hyperactivity disorder in 10-year-olds in a Swedish community. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(2):134–8.

Husarova D, Geckova AM, Blinka L, Sevcikova A, van Dijk JP, Reijneveld SA. Screen-based behaviour in school-aged children with long-term illness. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:130.

Kim JW, So WY, Kim YS. Association between asthma and physical activity in Korean adolescents: the 3rd Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBWS-III). Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(6):864–8.

Tercyak KP. Brief report: social risk factors predict cigarette smoking progression among adolescents with asthma. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(3):246–51.

Lee S, Shin A. Association of atopic dermatitis with depressive symptoms and suicidal behaviors among adolescents in Korea: the 2013 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:3.

Oh WO, Im Y, Suk MH. The mediating effect of sleep satisfaction on the relationship between stress and perceived health of adolescents suffering atopic disease: secondary analysis of data from the 2013 9th Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;63:132–8.

Adrian M, Charlesworth-Attie S, Vander Stoep A, McCauley E, Becker L. Health promotion behaviors in adolescents: prevalence and association with mental health status in a statewide sample. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2014;41(2):140–52.

Lampard AM, Maclehose RF, Eisenberg ME, Larson NI, Davison KK, Neumark-Sztainer D. Adolescents who engage exclusively in healthy weight control behaviors: who are they? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:5.

Allison KR, Adlaf EM, Irving HM, Hatch JL, Smith TF, Dwyer JJM, et al. Relationship of vigorous physical activity to psychologic distress among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(2):164–6.

Dube SR, Thompson W, Homa DM, Zack MM. Smoking and health-related quality of life among US adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(2):492–500.

Richardson LP, McCauley E, McCarty CA, Grossman DC, Myaing M, Zhou C, et al. Predictors of persistence after a positive depression screen among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1541–8.

Tercyak KP, Donze JR, Prahlad S, Mosher RB, Shad AT. Multiple behavioral risk factors among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer in the Survivor Health and Resilience Education (SHARE) Program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47(6):825–30.

Pronk NP, Anderson LH, Crain AL, Martinson BC, O’Connor PJ, Sherwood NE, et al. Meeting recommendations for multiple healthy lifestyle factors: prevalence, clustering, and predictors among adolescent, adult, and senior health plan members. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(Supp l):25–33.

Moradi-Lakeh M, El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Daoud F, Al Saeedi M, Basulaiman M, et al. The health of Saudi youths: current challenges and future opportunities. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:26.

Ohmann S, Popow C, Rami B, Konig M, Blaas S, Fliri C, et al. Cognitive functions and glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):95–103.

Soutor SA, Chen R, Streisand R, Kaplowitz P, Holmes CS. Memory matters: developmental differences in predictors of diabetes care behaviors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29(7):493–505.

Timko C, Stovel KW, Moos RH, Miller JJ 3rd. Adaptation to juvenile rheumatic disease: a controlled evaluation of functional disability with a one-year follow-up. Health Psychol. 1992;11(1):67–76.

MacDonell KK, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Naar S, Fernandez MI. Predictors of self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medication in a multisite study of ethnic and racial minority HIV-positive youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41(4):419–28.

Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Mellins CA. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-exposed youth: roles of caregivers, peers and HIV status. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(2):133–41.

Conner LC, Wiener J, Lewis JV, Phill R, Peralta L, Chandwani S, et al. Prevalence and predictors of drug use among adolescents with HIV infection acquired perinatally or later in life. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):976–86.

Olsson A, Hasselgren M, Hagquist C, Janson S. The association between medical conditions and gender, well-being, psychosomatic complaints as well as school adaptability. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(5):550–5.

Singh GK, Yu SM, Kogan MD. Health, chronic conditions, and behavioral risk disparities among US Immigrant children and adolescents. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(6):463–79.

Silburn SR, Blair E, Griffin JA, Zubrick SR, Lawrence DM, Mitrou FG, et al. Developmental and environmental factors supporting the health and well-being of Aboriginal adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2007;19(3):345–54.

Ardic A, Esin MN. Factors associated with healthy lifestyle behaviors in a sample of Turkish adolescents: a school-based study. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(6):583–92.

Nylander C, Seidel C, Tindberg Y. The triply troubled teenager—chronic conditions associated with fewer protective factors and clustered risk behaviours. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103(2):194–200.

Santos T, Ferreira M, Simoes MC, Machado MC, de Matos MG. Chronic condition and risk behaviours in Portuguese adolescents. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6(2):227–36.

Rintala P, Valimaa R, Tynjala J, Boyce W, King M, Villberg J, et al. Physical activity of children with and without long-term illness or disability. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(8):1066–73.

Han MA, Kim KS, Ryu SY, Kang MG, Park J. Associations between smoking and alcohol drinking and suicidal behavior in Korean adolescents: Korea Youth Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance, 2006. Prev Med. 2009;49(2–3):248–52.

Heflinger CA, Saunders RC. Physical and behavioral health of medicaid children in two Southern states. South Med J. 2005;98(4):429–35.

Haarasilta LM, Marttunen MJ, Kaprio JA, Aro HM. Correlates of depression in a representative nationwide sample of adolescents (15–19 years) and young adults (20–24 years). Eur J Public Health. 2004;14(3):280–5.

Mattila V, Parkkari J, Kannus P, Rimpela A. Occurrence and risk factors of unintentional injuries among 12- to 18-year-old Finns—a survey of 8219 adolescents. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19(5):437–44.

Huurre T, Aro H, Rahkonen O. Well-being and health behaviour by parental socioeconomic status: a follow-up study of adolescents aged 16 until age 32 years. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(5):249–55.

Miauton L, Narring F, Michaud PA. Chronic illness, life style and emotional health in adolescence: results of a cross-sectional survey on the health of 15–20-year-olds in Switzerland. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162(10):682–9.

Tremblay S, Dahinten S, Kohen D. Factors related to adolescents’ self-perceived health. Health Rep. 2003;14(Suppl):7–16.

Huurre TM, Aro HM. Long-term psychosocial effects of persistent chronic illness. A follow-up study of Finnish adolescents aged 16 to 32 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;11(2):85–91.

Williams R, Shams M. Generational continuity and change in British Asian health and health behaviour. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(9):558–63.

Authors’ contributions

DS and AA conceived and designed the study. DS and MKN screened the studies, extracted and analyzed the data. DS wrote the manuscript while AB, CRN and AA participated in data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Director of Kenya Medical Research Institute for granting permission to publish this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Funding

This work was supported by the funding from the Initiative to Develop African Research Leaders (IDeAL) Wellcome Trust award (Grant Number 107769/Z/15/Z) to DS as a Ph.D. fellowship and the Medical Research Council (Grant Number MR/M025454/1) to AA. This award is jointly funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under MRC/DFID Concordant agreement and is also part of the EDCTP2 program supported by the European Union. The funding bodies had no role in the study’s design, collection, analysis and interpretation of results, the writing of this manuscript or decision in submission of the paper for publication.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ssewanyana, D., Nyongesa, M.K., van Baar, A. et al. Health risk behavior among chronically ill adolescents: a systematic review of assessment tools. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 11, 32 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0172-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0172-5