Abstract

Background

Exposure to particulate matter (PM) is generally associated with elevated risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Elderly and obese subjects may be particularly susceptible, although short-term effects are poorly described.

Methods

Sixty healthy subjects (25 males, 35 females, age 55 to 83 years, body mass index > 25 kg/m2) were included in a cross-over study with 5 hours of exposure to particle- or sham-filtered air from a busy street using an exposure-chamber. The sham- versus particle-filtered air had average particle number concentrations of ~23.000 versus ~1800/cm3 and PM2.5 levels of 24 versus 3μg/m3, respectively. The PM contained similar fractions of elemental and black carbon (~20-25%) in both exposure scenarios. Reactive hyperemia and nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation in finger arteries and heart rate variability (HRV) measured within 1 h after exposure were primary outcomes. Potential explanatory mechanistic variables included markers of oxidative stress (ascorbate/dehydroascorbate, nitric oxide-production cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin and its oxidation product dihydrobiopterin) and inflammation markers (C-reactive protein and leukocyte differential counts).

Results

Nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation was reduced by 12% [95% confidence interval: −22%; −1.0%] following PM exposure, whereas hyperemia-induced vasodilation was reduced by 5% [95% confidence interval: −11.6%; 1.6%]. Moreover, HRV measurements showed that the high and low frequency domains were significantly decreased and increased, respectively. Redox and inflammatory status did not change significantly based on the above measures.

Conclusions

This study indicates that exposure to real-life levels of PM from urban street air impairs the vasomotor function and HRV in overweight middle-aged and elderly adults, although this could not be explained by changes in inflammation, oxidative stress or nitric oxide-cofactors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Exposure to particulate matter (PM) particularly in terms PM2.5 (mass of PM with aerodynamic diameter < 2.5 μm) in ambient air is associated with elevated risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality especially in risk groups with old age, obesity and/or diabetes [1,2]. The physiological mechanisms that link PM exposure and cardiovascular disease are not fully understood, but oxidative stress and inflammation are thought to be important with three plausible biological pathways leading to vasomotor dysfunction, arrhythmia, atherosclerotic progression, thrombogenesis and plaque instability: i) deposited PM trigger pulmonary inflammation with release of inflammatory and vasoactive mediators into the systemic circulation, ii) deposited ultrafine particles (aerodynamic diameter <100 nm) may translocate directly from the lungs to the bloodstream causing oxidative stress and inflammation with direct effects on the endothelium, or iii) deposited PM may activate neuronal signaling from the lungs with indirect effects on the cardiovascular function [1,3].

Exposure to ambient air PM has been associated with vasomotor dysfunction in both animal models and in humans [4]. Normal vessels are protected from shear stress hemodynamic forces by vasodilation dependent on activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) that generates NO by converting L-arginine to L-citrulline in the presence of molecular oxygen. Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is an essential cofactor for eNOS. The oxidized form of BH4, dihydrobiopterin (BH2), can cause eNOS uncoupling with production of superoxide anion radicals, which react with NO forming peroxynitrite, a potent oxidant [5,6]. An animal study indicated that exposure to diesel exhaust, the most important source of urban ultrafine particles, increased vasoconstriction through decreased NO bioavailability by uncoupling eNOS and decreased levels of BH4 [7]. Ex vivo exposure of animal aorta segments to diesel exhaust PM directly inhibited the relaxation response, whereas this response was restored by addition of superoxide dismutase that degrades superoxide anion radicals [8]. Moreover, studies with controlled exposure to diesel exhaust in humans have indicated that vasodilation response was impaired both related to endothelial stimulation to NO production and to administration of an NO donor [3].

Ascorbic acid (AA) is a potent intracellular and circulatory antioxidant, which together with its 2-electron oxidation product, dehydroascorbate (DHA), are used as biomarkers for oxidative stress in plasma [9]. Moreover, AA appears to increase the NO bioavailability and alleviate endothelial dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease [10]. This is possibly through preventing oxidation of BH4, promoting recycling of BH4 from its oxidized form, and/or through increasing gene transcription or activity of eNOS [10]. In addition, AA is important for maintenance of the endothelial barrier function and regulation of NADPH oxidase activity involved in the inflammatory response [11].

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a measure of changed cardiac autonomic function, which has been linked to risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [12]. HRV has been widely studied in relation to exposure to ambient and occupational air pollution as recently summarized in a meta-analysis of 29 studies from 1999–2011 [13]. This supported an inverse relationship between exposure to PM and especially time domains of HRV expressed as standard deviation of NN intervals (SDNN) as well as changes in high frequency (HF) and low frequency (LF) domains. Acute exposure in traffic has been associated with a decline in HRV [14], whereas no change in HRV was seen after 1-h exposure to a high concentration of diesel exhaust [15]. Elderly humans may be particularly susceptible to effects of ambient air PM on HRV [16].

The aim of this randomized cross-over study was to assess the effect of 5-h exposure to PM from urban street air on endothelium dependent and independent vasomotor function and HRV time and frequency domains in a cohort of overweight middle-aged and elderly subjects believed to be more sensitive to the biological and physiological responses to inhaled urban air PM, although not yet documented consistently with respect to clinical outcomes [17]. Potential mechanisms of adverse effects were studied in terms of oxidative stress assessed as AA and DHA, BH4 availability, and inflammation markers in terms of leukocyte differential counts.

Results

Exposure levels

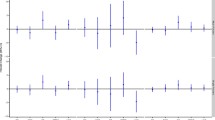

The main average exposure levels are given in Table 1. Participants were exposed to non-filtered air with average particle concentrations of 24 μg/m3 (PM2.5) and ~23, 000/cm3 with size distribution depicted in Figure 1. From the number size distributions and the effective densities the average PM1 was estimated to ~11-12 μg/m3. The particle number concentration in the exposure chamber was nearly 1:1 with the levels outdoor, compensating for different cut-offs of the two condensation particle counters used indoor and outdoor, respectively. This indicated that the transmission of particles from outdoor was high. Potentially, some of the volatile fraction of the particles might get lost during temperature conditioning of the air which was needed during winter time to keep the temperature in the exposure chamber stable. Filtering the air removed ~90% of the particles and slightly reduced concentration of NO2 (Table 1). Key drivers of the limited variation in air pollutants would be the day-to-day variation in wind direction, air mass origin and traffic intensity.

Average particle number size distribution and relative composition of particulate matter with diameter <1 μm in the exposure chamber assessed by a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer, a Differential Mobility Analyzer coupled in series with an Aerosol Particle Mass Analyzer and an Aerosol Mass Spectrometer.

Approximately 50% of the number of particles found at street level corresponds to fresh soot particles emitted from local traffic estimated from DMA-APM data [18] covering a size range of 50 to 450 nm. By mass, the corresponding fraction is only 20-25% explained by the low effective density of the aggregates at the peak in the submicron mass size distributions (e.g. ~250 nm).

The chemical composition [19] of the non-refractory PM1 mass was measured by means of aerosol mass spectrometry omitting the soot mass [18]. By combining with the soot mass fraction measured using a Differential Mobility Analyzer coupled in series with an Aerosol Particle Mass Analyzer (DMA-APM), the total chemical composition was estimated (Figure 1). It should be noted that the detailed characterisation was performed only during the first half of the exposures, and that the composition varied with the history of the air mass (long range transport), as discussed elsewhere [18].

Vasomotor function

Vasodilation was measured as induced by reactive hyperemia (RHI: reactive hyperemia index) and an NO donor (NTG-I: nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation index), representing endothelium dependent and independent mechanisms, respectively (Figure 2). RHI was 5% (95% CI: −11.6; 1.6) lower after 5-h exposure to PM as compared with the response after filtered air although not being statistically significant (P = 0.128). However, the NTG-I was statistically significantly reduced by 12% (95% CI: −22; −1.0) after the exposure to PM from urban street air (P = 0.033), although only 40 participants had this measurement due to a history of possible migraine or limited availability of medical supervision.

Heart rate variability

After 5-h exposure to PM from urban street air HRV was significantly altered in the frequency domains with a significant reduction of 6.0% (95% CI:-11; −1.1) in HFn and a significant increase of 7.5% (95% CI: 0.8; 15) in LFn, whereas there was no statistically significant difference in the time domain in terms of SDNN irrespective of baseline adjustment (Table 2). However, the SDNN was significantly reduced by 13% (95% CI:-24; −0.3; p = 0.045) immediately after entering the exposure chamber with non-filtered after as compared with the parallel measurement immediately after entering the chamber with filtered air.

Blood pressure, lipid profile, and metabolic markers

Median values of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, lipids (cholesterol and triglycerides), and metabolic biomarkers (fasting glucose and HbA1c) were within the normal reference ranges and confirmed the health status of the participants (Additional file 1: Table S1). The values were not affected by the exposure to non-filtered street air.

Oxidative stress and inflammation markers

The oxidative stress biomarkers BH4, BH2, biopterin, uric acid, AA and DHA changed over time (before and after air exposure), but there were no differences between exposure to PM from street air or filtered air (Table 3). Inflammation biomarkers including C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell (WBC) counts (leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils) showed no exposure-related changes.

Discussion

In this study, we found that 5-h exposure to PM from urban street air was associated with a statistically significant 12% reduction in NGT-I vasodilation and a 5% non-significant decrease in hyperemia-induced vasodilation in a possibly sensitive cohort of middle-aged and elderly overweight subjects. In addition, the HRV measurements indicated significantly decreased HFn and increased LFn after the 5-h exposure, whereas SDNN was decreased immediately after entering the chamber with PM. However, these vascular and cardiac effects were not associated with altered explanatory biomarker levels of oxidative stress, cofactors of NO production or inflammation.

Controlled exposure studies have demonstrated that 1-h inhalation of diesel exhaust at high concentrations (300 μg/m3) with exercise leads to impaired vasomotor function in young healthy subjects and cardiac ischemia in patients with coronary heart disease [20-22]. Here, we show that even at PM concentrations encountered at the street level (PM2.5 and black carbon concentrations of 24 and 3.9 μg/m3, respectively), vasomotor function was impaired in 55 to 83 years old overweight subjects after 5-h exposure without exercise. In support, ambient particle number concentrations were recently associated with low RHI among middle-aged subjects in Copenhagen, Denmark [23].

NO is a key endothelium-dependent vasodilating mediator and several lines of evidence have suggested that reduced NO bioavailability is associated with impaired vasomotor function after PM exposure [3,24]. A recent study using animal models suggested that diesel exhaust exposure, possibly through oxidative stress, depleted BH4 with formation of BH2 leading to uncoupling of eNOS and generation of superoxide and peroxinitrite at the expense of NO [7]. A possible role of BH4 is supported by the observation that co-infusion of BH4 (500 mg/min) can restore the reduced endothelium-dependent forearm vasodilation elicited by administration of acetylcholine in hypersensitive patients [25]. However, we found no change in BH4 or BH2 levels in relation to the PM exposure. Moreover, we observed primarily an altered endothelium-independent vasodilation, elicited by administration of NTG. Similarly, controlled exposure studies with pure diesel exhaust have found reduced responses to NO-related vasodilation elicited endothelium-dependently by bradykinin or acetylcholine and endothelium–independently by sodium nitroprusside [3,8]. The use of an NO synthase inhibitor (L-NMMA) in such a study indicated that NO generation is actually enhanced, but NO consumption is much further increased with resulting reduced bioavailability [3].

The reduced NO bioavailability due to consumption by ROS after airway exposure is supported by animal studies involving engineered nano-TiO2 [26]. Similarly, superoxide production appeared to explain impaired vasomotor function in rat aorta segments exposed to diesel exhaust particles ex vivo [8]. AA is an important antioxidant in both lung lining fluid [27] and plasma where it can increase NO bioavailability and restore endothelial function possibly by scavenging superoxide, preventing oxidation of BH4 and increase the expression and activity of eNOS [10]. Moreover, reduced levels of AA and high percentage of the oxidation product DHA in plasma are biomarkers of oxidative stress as shown in active and passive smokers [9,11]. Preincubation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells with AA for 24 hours reduced oxidative stress induced by 3-h exposure to exhaust PM from a light duty diesel engine supporting a role of AA for vascular effects of PM [28]. However, we found no effect of the exposure on the plasma levels of AA or DHA. This is consistent with lack of effect on AA following 2-h exposure to diesel exhaust at 200 μg/m3 in 10 adults with metabolic syndrome [29]. That study also found no effect on the lipid peroxidation products (F2-isoprostanes) and 8-oxo-7,8-deoxy-2’-guanosine in urine, measured by ELISA methods. Nevertheless, elevated levels of these biomarkers have been consistently associated with exposure to ambient air pollution [30]. Similarly, exposure to street air in Copenhagen, Denmark or in Cotonou, Benin, was associated with increased oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in peripheral blood mononuclear cells [31-33]. Although, the present exposure to PM from street air or diesel exhaust did not affect the levels of AA, DHA, BH4 or BH2 to an extent that explains the changed vasomotor function likely due to increased consumption of NO, it cannot be excluded that AA and BH4 concentrations were changed locally in the vessel wall without being reflected in forearm venous plasma.

Decreased HRV is recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [34] and a recent meta-analysis concluded that decreased HRV in both time and frequency domains are associated with high ambient air PM levels [13]. In contrast, a controlled exposure study with diesel exhaust (300 μg/m3) for one hour with 32 healthy subjects and 20 patients with prior myocardial infarction showed no change in any of the HRV domains [15]. However, the same research group found that 3 hours exposure to wood smoke at similar mass level was associated with decreased HRV time and HF domains in 14 young healthy subjects, whereas the LF domain was marginally increased although not statistically significant [35]. In partial agreement with those results we found a significant decrease in the HF domain and an increase in the LF domain after exposure. This is also consistent with a decrease in HF HRV in an older group of research volunteers after controlled 2-h exposure to concentrated fine particulate matter from an airshed dominated by local traffic sources, long-range traffic-related PM and coal-burning power plants [16]. Controlled 2-h exposure to concentrated ambient air coarse PM in Los Angeles, USA, appeared to have similar effects with decreased parasympathetic influence on HRV in both asthmatic and healthy volunteers [36]. Moreover, there was a decrease in the HF domain in subjects with type 2 diabetes exposed to elemental carbon ultrafine particles at 50 μg/m3 for 2 hours [37], whereas a similar setup with healthy subjects showed no such HRV change [38]. In young female subjects, the HF domain was increased and the LF domain unchanged after exposure to burning candle emissions at PM concentrations of 200 μg/m3 for 30 and 90 min [39]. Accordingly, exposure for more than two hours might be required for detection of adverse HRV changes, where the HF domain could be most sensitive for 5 min recordings and elderly, obese and/or type 2 diabetics may be most susceptible. Although we after the 5-h exposure found no sign of change in the time domain of HRV irrespectively of baseline adjustment, SDNN was significantly reduced just after entry into the chamber with non-filtered air. This suggests an immediate, possibly neurally-mediated, effect and it also points to a weakness in our design where the measurements of HRV at baseline and at the end of exposure had to be performed under the same conditions. Another weakness with respect to the time domain of HRV is the short sampling time of 5 min.

Short-term high level exposure to urban air pollution (mean PM2.5 levels of 147μg/m3) and ozone (mean 121 ppb) have previously been shown to increase blood pressure [40], whereas no such effect was found after controlled exposure to diesel exhaust at even higher concentrations [15]. At our level of exposure to urban air PM and low ozone concentration there was no effect on blood pressure.

Elevated WBC counts and CRP are signs of inflammations. Controlled 1-h exposure to diesel engine exhaust did not affect WBC counts [3], whereas similar 3-h exposure levels appeared to increase monocyte and total leukocyte counts 20 hours later [41]. Similarly, 2-h exposure to concentrated ambient air PM with intermittent exercise caused an increase in pulmonary neutrophils, but no change in total leukocyte counts [42]. Elevated CRP levels and risk of diabetes have mainly been associated with long-term exposure to air pollution [43,44]. In our study WBC counts, CRP and metabolic markers including lipid profile, glucose levels and HbA1C were all in normal range despite the participants’ overweight and showed no change after 5-h PM exposure.

Our study had a strong cross-over design and a high statistical power with 60 overweight middle-aged and older adults, with supposed particular susceptibility, serving as their own control. However, possibly due to their weight-status our participants showed more day-to-day variation in RHI than we previously found among elderly subjects and we did not have power to show significance of a 5% decrease, although we could show a significant decrease in NTG-I among the 40 participants with this measurement. Moreover, the study of real-life exposure led to some variation in both the levels and composition for each exposure session. We could not control exposure leading up to the study sessions except to avoid PM exposure by having the participants use a face mask on their way from home to the exposure chamber. It was only possible to perform physiological measurements and blood sampling on the participants before or in the beginning and just after the 5-h exposure. Thus, we could not assess the time course of effects during exposure and late effects might have been missed.

Conclusions

PM exposure from traffic caused vasomotor dysfunction and reduced HRV in overweight middle-aged and elderly subjects indicating adverse cardiovascular effects at real-life exposure levels. The vasomotor dysfunction appeared related to depletion of NO rather than reduced endothelial production of NO.

Materials and methods

Study population

Participants were invited by posting notices in local newspapers and handing out flyers in the area of Copenhagen, Denmark. We recruited 60 healthy, middle-aged and older (>55 years), overweight (body mass index, BMI > 25 kg/m2), nonsmoking (defined as cessation of smoking at least 1 year before the study) participants (25 men and 35 women) with no personal history of cardiovascular diseases (see Additional file 1: Table S2 for further characteristics). Of the participants 27 were never-smokers, whereas the 33 former smokers stopped smoking on average 20 years prior to the study. Subjects taking vasoactive drugs were not allowed into the study, but some participants took medicine in terms of analgesic or antirheumatic drugs (11), hormone related drugs (10), antihistamines (5), sedatives or antidepressants (5), lipid lowering drugs (3), proton pump inhibitors (2), bronchodilators (2), antibiotics (2) or none (28). The participants were asked to maintain their usual life-style, diet and use of medicine throughout the study period. The study was reviewed and approved by The Committees on Health Research Ethics in the Capital Region of Denmark (H-3-2011-074) and in accordance with the Helsinki II declaration. All participants were given both oral and written information and provided written consent before the study.

Study design

This study design was cross-over, repeated measures, where participants served as their own control with a blinded and randomized order of exposure to particle filtered or non-filtered outdoor air. Each participant was studied twice with 5 hours in an exposure chamber and around 14 days between exposures, which included 1–4 participants simultaneously. The participants were instructed to wear a highly efficient face mask (Dust Respirator 8812; 3M, St. Paul, MN, USA) on the way from their home to the exposure chamber in order to prevent exposure to ambient air PM immediately before the experiments. This mask type has been shown to reduce symptoms and improve cardiovascular health measures in patients with cardiovascular disease walking in polluted air in Beijing, China [20].

The participants arrived fasting except for possible morning medicine and were served a standard continental breakfast after all baseline measurements were done. During the 5-h exposure, they were at rest and only allowed to leave the chamber in order to go to the bathroom. We collected blood samples and measured blood pressure and vasomotor function before entry into the exposure chamber and within 1 hour after exposure. All measurements were completed within a 7-month period, from November 2011 to end of May 2012.

To create exposure scenarios simulating real-life exposure in traffic, air from the curb-side of a street (Østersøgade) in central Copenhagen, Denmark, was introduced directly into the exposure chamber (collected ~5 m from the nearest tailpipe area). The traffic density on this road was 26,800 vehicles during daytime (6 am to 6 pm), of which 2.2% were diesel powered heavy duty (>3.5 tons) and 35% of the light duty vehicles have diesel-powered engines. The outdoor air was continuously pumped into the exposure chamber using two KVR-100 Channel ventilators (Øland A/S, Ballerup, Denmark) at 230 m3/h (pressure = 100 Pa) resulting in an air exchange of 5.3/h in the chamber. Heating devices, placed within the airstream, kept the chamber temperature constant. To create either high or low PM exposure levels in the chamber, the outdoor air was passed through custom built units, with or without High Efficiency Particulate Adsorption filters (Camfil FARR HEPA filter 226002A1; Camfil A/S Stockholm, Sweden). In both scenarios (with or without filtration), air flow and pressure were constant, whereas nitrogen oxides (NO, NO2), ozone and carbon monoxide were minimally affected by the filtration.

Exposure assessment

The air in the exposure chamber was monitored continuously throughout all exposures with respect to particle number concentrations and PM2.5 by means of a TSI 3007 condensation particle counter and a Dusttrak Aerosol Monitor 8520 equipped with a PM2.5 inlet (TSI, St. Paul, MN, USA), respectively. On most exposure occasions, the particle number size distributions was monitored using a custom built Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer, covering particles of diameters in the range 10–600 nm [18], whereas NO and NO2 were monitored using a chemiluminescence NOx monitor (Thermo 42i monitor, Theromo Scientific). On 16 exposure days with sham-filtration and 8 days with active filtration, PM2.5 from the exposure chamber was collected on Teflon filters (Pall Teflo 47mm) for mass and black carbon analysis by means of a PQ100 Basel PM2.5 sampler (EPA WINS) (BGI Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content on the filters was measured using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [45].

During the first half of the study, an intense campaign characterizing the outdoor air, at the precise same location as the exposure chamber study, was performed. Instruments included were a Differential Mobility Analyzer coupled in series with an Aerosol Particle Mass Analyzer [46] (DMA-APM, model 3600, Kanomax, Japan), a high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer [19] (HR-ToF-AMS, Aerodyne Research Inc., USA) and a ultrafine condensation particle counter (UCPC, TSI model 3025) running continuously outside the chamber allowing an estimation of the difference in concentrations at the curb-side and inside the exposure chamber. The DMA-APM allows size resolved determination of the particle effective density, which was used when determining the particle mass size distributions and total mass concentrations from the number size distributions. By extrapolating the mass-size distributions up to 1 μm using a log-normal distribution function, we showed that PM0.6 typically made up ~80-90% of PM1. The DMA-APM can differentiate between fresh soot aggregates from more compact aged particles when externally mixed [18]. The high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer allows online determination of the chemical composition of the non-refractory particulate mass.

Vasomotor function

Vasomotor function was measured non-invasively using the EndoPAT2000 (Itamar Medical Ltd, Cesaria, Israel) as described further in the Additional file 1 [32,47,48]. RHI was recorded in a finger probe as the vasodilation response to hyperemia after 5 min occlusion of the brachial artery flow with reference to a finger probe on the contralateral arm. After each exposure scenario, we subsequently measured the vasodilation induced in the contralateral arm by 5 mg nitroglycerin (NTG), an NO donor, placed under the tongue 5 min after the RHI measurement. NTG was administered to only 40 subjects, whereas a possible history of migraine or limited capacity for medical supervision precluded this treatment in the remaining subjects. NTG-I was calculated as the ratio of average amplitudes of the pulse wave signal after and before administration.

Heart rate variability

HRV was measured by Actiheart (CamNtech Ltd, U.K.) placed on the chest before entering the exposure chamber (see Additional file 1 for details). Analysis of HRV was done for the 5 min just after the participants had entered the chamber and the 5 min just before leaving. For each period we calculated the standard deviation (SDNN) of the interbeat intervals and the power for the LF (range 0.04-0.15 Hz) and HF (range 0.15-0.4 Hz), expressed in normalized units as HFn and LFn by dividing with the power in the frequency range 0.04-0.5 Hz, respectively.

Biomarkers in blood

In a droplet (20 μl) of blood, we determined glycated hemoglobin levels, white blood cell (WBC) count and differential profile: lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils and neutrophils with a multiplatform analyzer (Chempaq XBC, Denmark). Plasma CRP, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein and triglycerides were analyzed at the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Copenhagen University Hospital.

Both AA and BH4 are highly susceptible to oxidation and well validated methods for immediate handling and preservation of blood samples and for analyses were applied [49,50]. For determination of plasma AA and DHA 4 ml of venous blood was drawn into EDTA tubes and immediately placed on ice to avoid further oxidation. Plasma was within one min separated by centrifugation (16000g, 3 min, 4°C) and 400 μl was added to a MPA solution (10% meta-phosphoric acid w/v, 2 mM Na2EDTA). After centrifugation of this (16000g, 1 min, 4°C) the supernatant was stored at −80°C until analysis for AA and DHA by HPLC with electrochemical detection as described previously [51].

For determination of plasma BH2 and BH4, blood was drawn into K3-EDTA tubes containing 100 μl of a freshly made solution of dithioerythritol prepared by dissolving 40 mg in 1000 μl milli-Q water. After gentle turning the plasma was separated within one min by centrifugation (3000g, 3 min, 4°C) and stored at −80°C until analysis. BH2, BH4 and biopterin were determined by HPLC as previously described [49].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/IC software (version 13.0). Linear mixed effect models (xtmixed) were used to evaluate the effect of PM exposure on log-transformed outcomes for a normal distribution of the residuals. All outcomes in terms of measurements after exposure to non-filtered or filtered street air were adjusted for baseline level (before entering the exposure chamber) in order to account for day-to-day variation within an individual. For NTG-I no baseline value was available. Adjustment for BMI, age and gender were included to account for missing values for a few subjects. The percentage change in outcomes related to statistically significant effects of PM exposure was calculated with 95% confidence intervals from exponential transformation of the regression coefficients. Statistical significance was taken at P < 0.05. The sample size was based on the intra-individual variation in RHI found among elderly where an 8% change was found after filtration of the home indoor air for 48 h without using baseline adjustment [32]. A similar effect size would require 37 participants with type I and II error levels of 5% and 10%, respectively. A total of 60 participants were recruited in order to have sufficient power for adjustment for baseline values measured in the morning before exposure.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Ascorbic acid

- BH2 :

-

Dihydrobiopterin

- BH4 :

-

Tetrahydrobiopterin

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DHA:

-

Dehydroascobate

- DMA-APM:

-

Differential mobility - aerosol particle mass analyzer

- eNOS:

-

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- HF:

-

High frequency

- HRV:

-

Heart rate variability

- LF:

-

Low frequency

- NTG:

-

Nitroglycerin

- NGT-I:

-

Nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation index

- NO:

-

nitric oxide

- PM:

-

Particulate matter

- RHI:

-

Reactive hyperemia index

- SDNN :

-

Standard deviation of NN intervals

References

Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope III CA, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331–78.

Ruckerl R, Schneider A, Breitner S, Cyrys J, Peters A. Health effects of particulate air pollution: a review of epidemiological evidence. Inhal Toxicol. 2011;23:555–92.

Langrish JP, Unosson J, Bosson J, Barath S, Muala A, Blackwell S, et al. Altered nitric oxide bioavailability contributes to diesel exhaust inhalation-induced cardiovascular dysfunction in man. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004309.

Moller P, Mikkelsen L, Vesterdal LK, Folkmann JK, Forchhammer L, Roursgaard M, et al. Hazard identification of particulate matter on vasomotor dysfunction and progression of atherosclerosis. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2011;41:339–68.

Kietadisorn R, Juni RP, Moens AL. Tackling endothelial dysfunction by modulating NOS uncoupling: new insights into its pathogenesis and therapeutic possibilities. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E481–95.

Chen Q, Kim EE, Elio K, Zambrano C, Krass S, Teng JC, et al. The role of tetrahydrobiopterin and dihydrobiopterin in ischemia/reperfusion injury when given at reperfusion. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2010;2010:963914.

Knuckles TL, Lund AK, Lucas SN, Campen MJ. Diesel exhaust exposure enhances venoconstriction via uncoupling of eNOS. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:346–51.

Miller MR, Borthwick SJ, Shaw CA, McLean SG, McClure D, Mills NL, et al. Direct impairment of vascular function by diesel exhaust particulate through reduced bioavailability of endothelium-derived nitric oxide induced by superoxide free radicals. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:611–6.

Lykkesfeldt J. Measurement of ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid in biological samples. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2002. Chapter 7: Unit 7.6. 1-15.

Mortensen A, Lykkesfeldt J. Does vitamin C enhance nitric oxide bioavailability in a tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent manner? In vitro, in vivo and clinical studies. Nitric Oxide. 2014;36:51–7.

Lykkesfeldt J, Michels AJ, Frei B. Vitamin C. Adv Nutr. 2014;5:16–8.

Anonymous. Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:354–81.

Pieters N, Plusquin M, Cox B, Kicinski M, Vangronsveld J, Nawrot TS. An epidemiological appraisal of the association between heart rate variability and particulate air pollution: a meta-analysis. Heart. 2012;98:1127–35.

Nyhan M, McNabola A, Misstear B. Comparison of particulate matter dose and acute heart rate variability response in cyclists, pedestrians, bus and train passengers. Sci Total Environ. 2014;468–469:821–31.

Mills NL, Finlayson AE, Gonzalez MC, Tornqvist H, Barath S, Vink E, et al. Diesel exhaust inhalation does not affect heart rhythm or heart rate variability. Heart. 2011;97:544–50.

Devlin RB, Ghio AJ, Kehrl H, Sanders G, Cascio W. Elderly humans exposed to concentrated air pollution particles have decreased heart rate variability. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;40:76s–80s.

Gold DR, Mittleman MA. New insights into pollution and the cardiovascular system: 2010 to 2012. Circulation. 2013;127:1903–13.

Rissler J, Nordin EZ, Eriksson AC, Nilsson PT, Frosch M, Sporre MK, et al. Effective density and mixing state of aerosol particles in a near-traffic urban environment. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:6300–8.

DeCarlo PF, Kimmel JR, Trimborn A, Northway MJ, Jayne JT, Aiken AC, et al. Field-deployable, high-resolution, time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2006;78:8281–9.

Langrish JP, Li X, Wang S, Lee MM, Barnes GD, Miller MR, et al. Reducing personal exposure to particulate air pollution improves cardiovascular health in patients with coronary heart disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:367–72.

Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Robinson SD, Gonzalez M, Darnley K, Macnee W, et al. Diesel exhaust inhalation causes vascular dysfunction and impaired endogenous fibrinolysis. Circulation. 2005;112:3930–6.

Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Gonzalez MC, Vink E, Robinson SD, Soderberg S, et al. Ischemic and thrombotic effects of dilute diesel-exhaust inhalation in men with coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1075–82.

Karottki DG, Beko G, Clausen G, Madsen AM, Andersen ZJ, Massling A, et al. Cardiovascular and lung function in relation to outdoor and indoor exposure to fine and ultrafine particulate matter in middle-aged subjects. Environ Int. 2014;73C:372–81.

Knuckles TL, Buntz JG, Paffett M, Channell M, Harmon M, Cherng T, et al. Formation of vascular S-nitrosothiols and plasma nitrates/nitrites following inhalation of diesel emissions. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2011;74:828–37.

Higashi Y, Sasaki S, Nakagawa K, Fukuda Y, Matsuura H, Oshima T, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin enhances forearm vascular response to acetylcholine in both normotensive and hypertensive individuals. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:326–32.

Nurkiewicz TR, Porter DW, Hubbs AF, Stone S, Moseley AM, Cumpston JL, et al. Pulmonary particulate matter and systemic microvascular dysfunction. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2011;364:3–48.

Mudway IS, Stenfors N, Duggan ST, Roxborough H, Zielinski H, Marklund SL, et al. An in vitro and in vivo investigation of the effects of diesel exhaust on human airway lining fluid antioxidants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423:200–12.

Frikke-Schmidt H, Roursgaard M, Lykkesfeldt J, Loft S, Nojgaard JK, Moller P. Effect of vitamin C and iron chelation on diesel exhaust particle and carbon black induced oxidative damage and cell adhesion molecule expression in human endothelial cells. Toxicol Lett. 2011;203:181–9.

Allen J, Trenga CA, Peretz A, Sullivan JH, Carlsten CC, Kaufman JD. Effect of diesel exhaust inhalation on antioxidant and oxidative stress responses in adults with metabolic syndrome. Inhal Toxicol. 2009;21:1061–7.

Moller P, Loft S. Oxidative damage to DNA and lipids as biomarkers of exposure to air pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1126–36.

Avogbe PH, Ayi-Fanou L, Autrup H, Loft S, Fayomi B, Sanni A, et al. Ultrafine particulate matter and high-level benzene urban air pollution in relation to oxidative DNA damage. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:613–20.

Brauner EV, Moller P, Barregard L, Dragsted LO, Glasius M, Wahlin P, et al. Exposure to ambient concentrations of particulate air pollution does not influence vascular function or inflammatory pathways in young healthy individuals. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2008;5:13.

Vinzents PS, Moller P, Sorensen M, Knudsen LE, Hertel O, Jensen FP, et al. Personal exposure to ultrafine particles and oxidative DNA damage. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1485–90.

Tsuji H, Venditti Jr FJ, Manders ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, Feldman CL, et al. Reduced heart rate variability and mortality risk in an elderly cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;90:878–83.

Unosson J, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T, Muala A, Boman C, Nystrom R, et al. Exposure to wood smoke increases arterial stiffness and decreases heart rate variability in humans. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:20.

Gong H, Linn WS, Terrell SL, Anderson KR, Clark KW, Sioutas C, et al. Exposures of elderly volunteers with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to concentrated ambient fine particulate pollution. Inhal Toxicol. 2004;16:731–44.

Vora R, Zareba W, Utell MJ, Pietropaoli AP, Chalupa D, Little EL, et al. Inhalation of ultrafine carbon particles alters heart rate and heart rate variability in people with type 2 diabetes. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11:31.

Zareba W, Couderc JP, Oberdorster G, Chalupa D, Cox C, Huang LS, et al. ECG parameters and exposure to carbon ultrafine particles in young healthy subjects. Inhal Toxicol. 2009;21:223–33.

Hagerman I, Isaxon C, Gudmundsson A, Wierzbicka A, Dierschke K, Berglund M, et al. Effects on heart rate variability by artificially generated indoor nano-sized particles in a chamber study. Atmos Environ. 2014;88:165–71.

Urch B, Silverman F, Corey P, Brook JR, Lukic KZ, Rajagopalan S, et al. Acute blood pressure responses in healthy adults during controlled air pollution exposures. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1052–5.

Xu Y, Barregard L, Nielsen J, Gudmundsson A, Wierzbicka A, Axmon A, et al. Effects of diesel exposure on lung function and inflammation biomarkers from airway and peripheral blood of healthy volunteers in a chamber study. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:60.

Ghio AJ, Kim C, Devlin RB. Concentrated ambient air particles induce mild pulmonary inflammation in healthy human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:981–8.

Li Y, Rittenhouse-Olson K, Scheider WL, Mu L. Effect of particulate matter air pollution on C-reactive protein: a review of epidemiologic studies. Rev Environ Health. 2012;27:133–49.

Andersen ZJ, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Ketzel M, Jensen SS, Hvidberg M, Loft S, et al. Diabetes incidence and long-term exposure to air pollution: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:92–8.

Kliucininkas L, Martuzevicius D, Krugly E, Prasauskas T, Kauneliene V, Molnar P, et al. Indoor and outdoor concentrations of fine particles, particle-bound PAHs and volatile organic compounds in Kaunas, Lithuania. J Environ Monit. 2011;13:182–91.

Ehara K, Hagwood C, Coakley KJ. Novel method to classify aerosol particles according to their mass-to-charge ratio - Aerosol particle mass analyser. J Aerosol Sci. 1996;27:217–34.

Forchhammer L, Moller P, Riddervold IS, Bonlokke J, Massling A, Sigsgaard T, et al. Controlled human wood smoke exposure: oxidative stress, inflammation and microvascular function. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2012;9:7.

Karottki DG, Spilak M, Frederiksen M, Gunnarsen L, Brauner EV, Kolarik B, et al. An indoor air filtration study in homes of elderly: cardiovascular and respiratory effects of exposure to particulate matter. Environ Health. 2013;12:116.

Mortensen A, Hasselholt S, Tveden-Nyborg P, Lykkesfeldt J. Guinea pig ascorbate status predicts tetrahydrobiopterin plasma concentration and oxidation ratio in vivo. Nutr Res. 2013;33:859–67.

Lykkesfeldt J. Ascorbate and dehydroascorbic acid as biomarkers of oxidative stress: validity of clinical data depends on vacutainer system used. Nutr Res. 2012;32:66–9.

Lykkesfeldt J. Ascorbate and dehydroascorbic acid as reliable biomarkers of oxidative stress: analytical reproducibility and long-term stability of plasma samples subjected to acidic deproteinization. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2513–6.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jørgen H. Skotte, who wrote the algorithm for and calculated HRV. Bo Strandberg and Lisa Svedbom are thanked for analyses of PM2.5 filters. The detailed aerosol characterization was provided by Staffan Sjogren, Axel C. Eriksson, Aneta Wierzbicka, Mia Frosch, Patrik T. Nilsson, Joakim H. Pagels, Jakob Löndahl, Erik Z. Nordin, Erik Swietlicki and Birgitta Svenningsson from the Aerosol Group at Lund University. Annie B. Kristensen, Joan Frandsen, Belinda Bringtoft, Lisbeth Sand Carlsen and Julie Hansen are thanked for excellent technical assistance. The study was supported by the Danish Heart Foundation grant no A3525. JL is supported by the LifePharm Centre for In Vivo Pharmacology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JGH, SL and PM contributed the concept and design of the study. JGH was responsible for ethical committee approval, recruitment of subjects, coordination and conduction of the study and acquisition of health-related data. JR and GS were responsible for characterisation of the exposure. JL was responsible for analysis of AA, DHA, BH2 and BH4. JK was responsible for analysis of HRV data. JGH, PM and SL analysed and interpreted the health-related data. JGH drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised by SL and PM. All authors have read, corrected, and approved the manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Measurement of vasomotor function. Measurement of Heart rate variability (HRV). Table S1. Blood pressure and metabolic biomarkers in subjects before and after 5-h exposure in a chamber with or without filtration of inlet air from an urban street. Table S2. Characteristics of the study participants as number or median (5;95% percentiles).

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hemmingsen, J.G., Rissler, J., Lykkesfeldt, J. et al. Controlled exposure to particulate matter from urban street air is associated with decreased vasodilation and heart rate variability in overweight and older adults. Part Fibre Toxicol 12, 6 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-015-0081-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-015-0081-9