Abstract

Background

Despite the growing utility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) for cardiac morphology and function, sex and age-specific normal reference values derived from large, multi-ethnic data sets are lacking. Furthermore, most available studies use a simplified tracing methodology. Using a large cohort of participants without history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or risk factors from the Canadian Alliance for Healthy Heart and Minds, we sought to establish a robust set of reference values for ventricular and atrial parameters using an anatomically correct contouring method, and to determine the influence of age and sex on ventricular parameters.

Methods and results

Participants (n = 3206, 65% females; age 55.2 ± 8.4 years for females and 55.1 ± 8.8 years for men) underwent CMR using standard methods for quantitative measurements of cardiac parameters. Normal ventricular and atrial reference values are provided: (1) for males and females, (2) stratified by four age categories, and (3) for different races/ethnicities. Values are reported as absolute, indexed to body surface area, or height. Ventricular volumes and mass were significantly larger for males than females (p < 0.001). Ventricular ejection fraction was significantly diminished in males as compared to females (p < 0.001). Indexed left ventricular (LV) end-systolic, end-diastolic volumes, mass and right ventricular (RV) parameters significantly decreased as age increased for both sexes (p < 0.001). For females, but not men, mean LV and RVEF significantly increased with age (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Using anatomically correct contouring methodology, we provide accurate sex and age-specific normal reference values for CMR parameters derived from the largest, multi-ethnic population free of CVD to date.

Clinical trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02220582. Registered 20 August 2014—Retrospectively registered, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02220582.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last several years, cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging has been established as a reproducible reference standard for the quantification of chamber volumes, function, and mass in the evaluation of various cardiac diseases [1]. Despite growing awareness of sex/gender and age-related differences in diagnostic approaches [2], CMR-based reference values for ventricular and atrial parameters, specific to sex and age groups are lacking, with conflicting data derived from small or heterogeneous populations [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Furthermore, previously available reference values were limited by sample cohorts with established cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, discrete ethnic populations [10, 12,13,14], or by a contouring methodology that excluded trabecular tissue and papillary muscle from left ventricular (LV) mass, thus was not anatomically accurate [15].

A large prospective, multi-center cohort through the Canadian Alliance for Healthy Heart and Minds (CAHHM) provides a unique opportunity to investigate normal ranges of physiologic parameters, as well as the association with socio-environmental and contextual factors, CVD risk, subclinical disease, and other related chronic disease outcomes [16]. In addition to extensive clinical assessments consisting of health questionnaires, physical measurements, and blood sample collection, CAHHM participants also underwent a comprehensive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, heart, carotid artery, and abdomen [16]. A total of 8,580 participants were recruited with the opportunity to better understand the data of those who completed CMR imaging.

Given the widespread use and the incremental prognostic value of CMR, the objectives of this study were to establish a robust set of reference values for ventricular/atrial volumetric and functional parameters, and to understand the relationship with age and sex in participants without a history of established CVD or CVD risk factors.

Methods

Study population

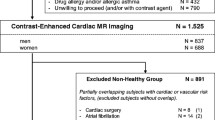

The CAHHM is a prospective study of participants recruited through existing research cohorts, with each separate inclusion and exclusion criteria, as previously described [16]. Research ethics approval was granted by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board, with consent obtained at each collaborating site as per site-specific regulations prior to participation in the study. Selection criteria specific to CAHHM included males and females, between the ages of 35 and 75 years, who were willing to undergo an MRI scan and all other required study procedures. A parallel Alliance-First Nations cohort was also undertaken in partnership with eight First Nations communities, however, the data was not included in this sub-study. Balanced representation of participants across different age strata 35–44, 44–54, 55–64, and 65–74 years with approximately 50% or more recruitment of females was also ensured [16]. Additional file 1: Figure S1 shows the flowchart (for participant selection and recruitment). For the purposes of this analysis, participants with CVD defined as a clinical history of angina or myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure and/or other cardiac disease, prior coronary artery bypass grafting, or percutaneous coronary intervention were excluded. Participants with hypertension defined as a resting elevated blood pressure > 140/80 mmHg, diabetes, obesity (body mass index (BMI) > 30), smoking, or dyslipidemia were also excluded. Finally, participants were ineligible for recruitment if they had contraindications to CMR, including claustrophobia, pregnancy, non-compatible pacemaker/defibrillator devices, and intraocular/intracranial metallic materials. This study complied with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist.

CMR protocol

CMR images were acquired at collaborating sites with the participants in supine position using conventional CMR systems (1.5 T or 3 T) and a cardiac (preferred) or chest phased-array surface coil with ≥ 8 receiver elements. Following appropriate magnetic shimming, standard localization was performed with a single-breath hold, retrospective electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated balanced steady state free precession (bSSFP) sequence. When available, bSSFP frequency scouting was performed to minimize susceptibility artifacts in the myocardium. Cine images were acquired for LV and right ventricular (RV) volumetric and functional parameters in both the long axis (2 slices) and contiguous short axis (SAx) views (12–14 slices). Field of view was 360 mm, voxel size ranged from 0.9 to 1.2 mm, while slice thickness was 8 mm, with a 2 mm gap.

Image analysis

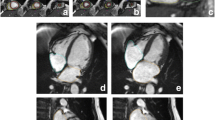

CMR images were analysed offline by blinded readers at a core lab (Montreal Heart Institute, Montreal Canada) using certified software (cvi42, version 4, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., Calgary, Alberta, Canada). The cine SAx stack was used to perform quantitative LV/RV functional and volumetric evaluations. Epicardial and endocardial contours were traced manually or semi-automatically using the built-in “threshold tool” with attention to anatomy and potential image artefacts (Fig. 1). Anatomical accuracy was verified by carefully tracing contours for LV mass at end-systole, including papillary muscles and trabecular tissue into LV mass. There are several reasons for using the systolic phase for quantifying LV mass, as discussed in detail by Riffel et al. [15] Firstly, the overall length of the line defining the endocardial border is shorter and thus, a shorter length susceptible to errors. Secondly, the systolic phase typically has fewer slices than the diastolic phase, thus less contours to draw and less chances for errors. Finally, during systole, the inter-trabecular recesses are closed and therefore, there is lower probability for partial volume errors (Fig. 2). For additional reference, LV mass in end-diastole was also measured and reported in the supplementary materials.

For LV volume calculations, the entire outflow track was included into the end-diastolic and end-systolic phases. Consistent with the LV evaluation, RV volume contours were segmented, excluding the trabeculae and papillary muscles from the blood pool. Expert consensus from the research committee deemed RV mass measurements were not reliable to be used routinely in the clinical setting. Therefore, RV mass was not measured nor reported, so as to avoid confusion or misguidance.

Left atrial (LA) volume was derived from the long axis 2-chamber and 4-chamber views, according to the Biplane method [17]. Maximum LA volume was measured at end-systole, immediately before mitral valve opening and minimum LA volume was measured at end-diastole, immediately before mitral valve closure [17]. Image quality was qualitatively assessed by expert observers as either good, acceptable, or poor with consideration of anatomical structures or artefacts related to breathing, inadequate ECG triggering (blurring), flow, chemical shift (T2* susceptibility), or ghosting (T1 effects). Only participants with good or acceptable image quality were included in the final data analysis.

Inter-observer and intra-observer quality assurance

Based on derived sample size calculations for intraclass correlation (ICC) [18], roughly 27 subjects (assuming there are 2 raters, 50 measurements in total) and 17 subjects (assuming there are 4 raters; 100 measurements in total) were estimated to detect ICC = 0.86 with 80% power. Therefore, the evaluation of intra- and inter-observer reliability was performed using 25 randomly selected CMR studies on four variables: end-diastolic volume (EDV), end-systolic volume (ESV), stroke volume (SV), and ejection fraction (EF) for both the LV and RV. CMR images with altered protocols, phantoms scans for quality control purposes, files sent more than once by the users, images sent with incorrect registry information, images not analyzable due to poor quality, and missing or incomplete CMR exams were excluded from this analysis. For the intra-observer reliability, the CMR studies were read twice by the assigned observers. A minimum delay of 4 weeks between the first and second readings was used to minimize observer bias. For inter-observer reliability, two readers were included in the analyses. The level of experience among the two observers ranged from expert (more than 15 + years of experience in CMR contouring and analysis) to 5 years of CMR contouring experience. The readers underwent standardized protocol training using practice cases to ensure contours were drawn accurately and consistently prior to analyzing participant data. As each reader made repeated measurements, methods described in Shrout and Fleiss [19] were not applicable. Hence, ICC were calculated to assess the inter- and intra-observer variability, as described in Eilasziw et al. [20] and visually depicted using Bland–Altman plots.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for males and females were calculated for the risk factors and baseline characteristics and presented as mean (SD) or proportions (%). For continuous normal and non-normal variables, Two-sample T-test or Mann-Whitney U tests were used respectively to compare mean between females and men. Similarly, a Chi-square test was applied to compare the proportions. Means of CMR measurements between males and females were compared with two sample tests using a Satterthwaite approximation for the degrees of freedom. Normal reference ranges are defined as the 95% prediction interval, which is calculated by [12]

For measured CMR variables (volume, mass) and derived variables (ejection fractions), reference ranges were calculated after excluding the outliers and presented in all the reference tables. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) and all figures were created using R (version 3.5.3. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 8580 participants consented for the study with CMR data available for 8258 subjects. Due to history of CVD (10%) or missing LV parameters/poor image quality (5%), 1223 subjects were excluded (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Of the remaining 7035 participants, 3812 (54%) with history of CVD risk factors were excluded from the final analysis. Therefore, a total of 3,206 participants with CMR examinations were included in the analysis (2080 females, 65%). The mean age for males was 55.1 ± 8.8 and 55.2 ± 8.4 for females (p = 0.57). Details of the baseline demographics for the participants with CVD or CVD risk factors, by sex and age groups are shown in Table 1.

Overall, females had a lower BMI than males (p < 0.001), but a higher percentage of body fat (p < 0.001). Additionally, a small proportion in males (17%) and females (22%) reported a positive family history of CVD. Most subjects were white Caucasian (77% females, 77% men, p = 0.20). Approximately 17% were of Chinese ethnicity and approximately 4% were of South Asian ethnicity.

Influence of sex on CMR-derived volumetric parameters

Table 2 shows sex-specific means ± SD for LV, RV and LA parameters indexed to body surface area (BSA) with derived normal reference ranges for all participants. The corresponding absolute values, and values indexed to height are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Additional file 2: Tables S1a–S1b). Absolute values, and values indexed to height or BSA for the different race/ethnicities are also reported for white Caucasians (Additional file 2: Table S4a–S4c), Chinese (Additional file 2: Table S5a–S5c), and South Asians populations (Additional file 2: Table S6a–S6c).

Overall, ventricular volumes and mass were greater in males than in females. The indexed mean LVSV (46 ml/m2 ± 8), LVEDV (74 ml/m2 ± 13), LVESV (28 ml/m2 ± 7), and LV mass (61 g/m2 ± 10) for males were significantly larger than the indexed LVSV (42 ml/m2 ± 7), LVEDV (65 ml/m2 ± 11), LVESV (23 ml/m2 ± 6), and LV mass (48 g/m2 ± 8) for females, respectively (all p < 0.001). Similarly, indexed RVSV (45 ml/m2 ± 8), RVEDV (86 ml/m2 ± 16) and RVESV (41 ml/m2 ± 11) for males were larger than indexed RVSV (42 ml/m2 ± 7), RVEDV (72 ml/m2 ± 13) and RVESV (31 ml/m2 ± 8) for females (all p < 0.001). However, LVEF (62% ± 6) and RVEF (53% ± 6) for males were significantly less than LVEF (64% ± 6) and RVEF (58% ± 6), (p < 0.001) for females.

Age-STRATIFIED CMR-derived volumetric parameters

Age-stratified indexed reference ranges are shown for males and females in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Corresponding absolute values (Additional file 2: Tables 2a and 2b) and values indexed to height (Additional file 2: Tables 3a and 3b) can be found in Supplementary Materials for males and females, respectively. Age groups were stratified into 4 clinically relevant categories by decade of age (35 ≤ to < 45 years, 45 ≤ to < 55 years, 55 ≤ to < 65 years, and 65 ≤ to < 75 years), with the greatest representation from the middle-aged population from 45 to 64 years (71% of males and 74% of females).

Overall, indexed LVESV and LVEDV decreased as age increased (Additional file 1: Figure S2A and S2B) for both males and females (p < 0.001). Indexed LV mass also decreased with advancing age for males (p < 0.001) and females (p < 0.001) (not shown). The same was seen with indexed RV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes for males and females (not shown, p < 0.001). For men, there was no significant difference between LVEF across the different age strata (Additional file 1: Fig. 2C, p = 0.1985), but RVEF did increase with advancing age (not shown, p = 0.009). For females, there were significant differences seen in the LVEF and RVEF, whereby the mean EF values increased with advancing age (Fig. 2C, p < 0.001).

Intra- and inter-observer Reliability

A summary of the inter and intra-observer reliability are listed in Table 5. Moderate to excellent intra- and inter-observer variability were demonstrated for all measured parameters. Representative examples of Bland–Altman plots for LV stroke volume are shown in Additional file 1: Figures S3 and S4.

Discussion

Among participants without known CVD or CV risk factors included in this large multi-ethnic population-based sample of 3206 adults aged 35–75 years, we provide accurate age- and sex-specific CMR-derived reference values for biventricular volumes, function, and mass and LA volume. Parameters normalized to BSA and height, as well as absolute values were reported, as volumetric parameters and mass are correlated with body habitus [5, 21]. BSA, which accounts for both height and weight, is the adjustment standard recommended by other societies, including those for echocardiography. [22] Clinical-decision making based solely on absolute values, while convenient, allow for potential under- or overestimation of chamber volumes and mass, undermining the utility of CMR.

Strength and novelty of the study cohort

Multiple areas highlight the strength and novelty of the CAHHM CMR cohort, including the large recruitment of participants from a multi-ethnic population, absence of confounding pathological cardiovascular conditions, good representation of females, and finally, adherence to high imaging standards for quality assurance (Table 6). Previous studies have sought to provide CMR-based reference values for the clinical assessment of ventricular and atrial parameters. However, our sample population is the largest known to date, with prior sample sizes ranging from 60 participants [9] to the most recent publication by Petersen et al. that included 800 subjects for analysis [12] (Table 6). A large sample population ensures more accurate mean reference values, identification of outliers, and overall smaller margins of errors. This is particularly important in conditions such as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction that require highly accurate evaluation of ventricular function and volume to properly guide medical therapy, as research now demonstrate increased mortality when LVEF exceeds 65% [23, 24].

Despite growing momentum for the increasing utility of CMR in clinical routine, there is lack of agreement on specific standards for quantitative parameters. The latest Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) 2018 expert consensus document for imaging endpoints recognize that there is moderate variability in normal ranges depending on the population studied and method of quantification [1]. The recommended resource, however, for normal values as per the SCMR is from a review by Kawel-Boehm et al. that summarized the findings of three publications using the bSSFP CMR sequence of very small sample sizes and heterogeneous ethnic population by Alfakih et al. 2003 (n = 60), Hudsmith et al. (n = 108), and Maceira et al. (n = 120) (Table 6). [11] Thus, as expected with small sample sizes, there were differences between findings by Kawel-Boehm et al. and our own. For instance, the ventricular reference values for indexed LVEDV and LV mass reported by Kawel-Boehm et al. were different by nearly 10 ml/m2 when compared to the sex-specific values from our study, which incorporated data from over 3000 individuals. Furthermore, Kawel-Boehm et al. provide adult parameters for age stratified by younger or older than 60 years of age and not specific reference values by age decade, limiting the robust clinical application.

With strict adherence to the research protocols outlined by the CAHHM committee, substantial efforts were made to ensure the study population was indeed free of underlying CVD or risk factors, excluding over 64% of consented participants. The sample population also included participants from different race/ethnicities including white Caucasians, South Asians, and Chinese descent, allowing for increased generalizability and broad application of the reference values. Researchers have previously reported variability in LV volumes and mass across the different races/ethnicities and as such, we provide normal references values for the separate groups in the supplemental materials [25]. We also report smaller indexed LV volumes and mass in the Chinese population compared to subjects from European descent (white Caucasians) [14, 26], and note similar volumes and mass in the South Asians compared to the white Caucasians.

When comparing our results to the previous reference values reported by Petersen et al. using the United Kingdom (UK) Biobank cohort, notable differences in the indexed mean LV and RV parameters were seen. For example, normal indexed LVEDV for females in our study was 65 ml/m2 ± 11 (range 45 to 86 ml/m2), which is different when compared to the normal indexed LVEDV by Petersen et al. for overall females of 74 ml/m2 ± 12 (range 54 to 94 ml/m2). We suspect the discrepancy may be due to the different contouring approach, which is an important contribution of our normative data to the current literature. In contrast to some previous studies, our contouring method of including the papillary muscles and trabecular structures as myocardial mass (and not as blood) is anatomically and functionally correct [15], and recommended by the recently updated recommendations of the SCMR [27]. The exclusion of papillary muscles from LV mass has been shown to lead to an underestimation of LV hypertrophy [28]. Opponents may argue that this contouring approach suffers from partial volume effects, averaging trabeculations with the blood pool, thus leading to overestimation of LV mass and underestimation of LV volume. However, the problem of partial volume may actually lead to errors in both directions, i.e. under- and overestimation [29]. Using the simplified method of drawing the contour to define the arbitrary “cutoff” line may be subjected to additional observer variability and errors (Fig. 3). We emphasize that several previous studies have also used the anatomically correct contouring [9, 13, 30], with ex vivo validations showing very good agreement [31, 32] and researchers demonstrated that this method provides more reliable values [15]. Yet, many centers and even large cohort studies, such as the UK Biobank [33] use a simplified method that cuts off papillary and trabecular tissue, explaining the larger volumes observed in the UK Biobank cohort. Recommendations concede that such a simplification is inaccurate, but “allow” for this simplification for practicality reasons [34]. Our study is the largest cohort to utilize the anatomically and functionally correct contouring method to date, demonstrating its feasibility for clinical and research settings.

Anatomically correct contouring method for left ventricular (LV) mass. Papillary muscles and trabecular structures are included as myocardium (and not as blood) (right panel). Using the simplified method (left) of drawing the contour to define the arbitrary “cutoff” line (yellow arrows) may be subjected to additional observer variability and errors

Dependence of values on sex and age on LV and RV volumes, function, and mass

It has long been known that sex has significant independent influence on normal values for biventricular volumes and mass [35]. Similarly, our study found that LV and RV volumes were significantly smaller in females compared to men, and that LV mass was also larger in males than females [35]. Age also has a significant influence on ventricular volumes, whereby LV and RV volumes are known to decrease with advancing age, with significant differences between each age strata [12, 21]. The influence of age on indexed LV mass to BSA, however, has not been well understood. Among the studies that specifically included age-specific reference ranges or age-associated statistical analyses—using similar CMR protocols with a cine bSSFP approach—the UK Biobank observed, upon normalization to BSA, LV mass did not change significantly with age in either sex [12]. Le Ven et al. in their study of 434 white Caucasian adults without CVD or risk factors, reported that, while age had an independent influence on most ventricular measurements, it was not significantly associated with LV mass [13]. In our study, the influence of age was significant on indexed LV mass in both sexes, likely due to the inclusion of papillary muscles, which reduces accuracy compared to autopsy, but results in higher precision, smaller observer variability, and allows for more robust clinical application [1].

We found values of LVEF and RVEF were significantly higher for females due to higher stroke volumes, which is consistent with previous large CMR studies, including the Dallas Heart Study and trials using computed tomography [2, 12, 36]. LVEF and RVEF increases with age in both sexes, with a more pronounced relationship seen in females than men. However, consistent with previous findings, the normal reference ranges across the different age strata remained similar [12].

Study limitations

Firstly, while the overall composition of the study population included participants from different ethnicities, the majority were of white Caucasian background, which may limit the overall generalizability of the measurements. However, measurements were indexed to BSA to help reduce the confounding effects of ethnicity. Secondly, based on considerations for feasibility, cost, and research limitations, observer variability was performed in 25 cases (representing ~ 10% of the study population) for only RV and LV parameters, measurements which frequently show inconsistencies in the clinical environment. Our study demonstrated overall good quality assurance and based on sample size calculations, the addition of more cases or readers would not contribute further meaningful findings. Lastly, owing to logistical issues, normative values for RA data was not provided in this paper. An alternative paper will be released to separately address accurate measurements of RA and RV parameters. The primary focus for this paper, however, was to provide a robust set of normal reference values for ventricular parameters using the anatomically correct contouring method. Therefore, the results of this study still adds significant value to existing normative references.

Conclusion

Recognizing the significant influence of sex and age on volumetric parameters is particularly important in the clinical evaluation of several cardiovascular conditions. Using anatomically correct contouring methodology, this large, multi-ethnic cohort from the Canadian Alliance for Healthy Heart and Minds offers a robust set of CMR-derived sex and age-specific reference values that can be used to distinguish cardiac impairment in clinical and research settings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BSA:

-

Body surface area

- bSSFP:

-

Balanced steady state free precession

- CAHHM:

-

Conadian Alliance for Healthy Heart and Minds

- CMR:

-

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- EDV:

-

End-diastolic volume

- EF:

-

Ejection fraction

- ESV:

-

End-systolic volume

- LA:

-

Left atrium/left atrial

- LV:

-

Left ventricle/left ventricular

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RV:

-

Right ventricle/right ventricular

- SAx:

-

Short axis

- SCMR:

-

Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance

- SV:

-

Stroke volume

References

Puntmann VO, Valbuena S, Hinojar R, et al. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) expert consensus for CMR imaging endpoints in clinical research: part I. Analytical validation and clinical qualification. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2018;20(1):67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-018-0484-5.

Gebhard C, Buechel RR, Stahli BE, et al. Impact of age and sex on left ventricular function determined by coronary computed tomographic angiography: results from the prospective multicentre CONFIRM study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;18(9):990–1000. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jew142.

Yeon SB, Salton CJ, Gona P, et al. Impact of age, sex, and indexation method on MR left ventricular reference values in the Framingham Heart Study offspring cohort. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41(4):1038–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.24649.

Cain PA, Ahl R, Hedstrom E, et al. Age and gender specific normal values of left ventricular mass, volume and function for gradient echo magnetic resonance imaging: a cross sectional study. BMC Med Imaging. 2009;9:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2342-9-2.

Salton CJ, Chuang ML, O’Donnell CJ, et al. Gender differences and normal left ventricular anatomy in an adult population free of hypertension. A cardiovascular magnetic resonance study of the Framingham Heart Study Offspring cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(6):1055–60.

Lorenz CH, Walker ES, Morgan VL, Klein SS, Graham TP Jr. Normal human right and left ventricular mass, systolic function, and gender differences by cine magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 1999;1(1):7–21.

Marcus JT, DeWaal LK, Gotte MJ, van der Geest RJ, Heethaar RM, Van Rossum AC. MRI-derived left ventricular function parameters and mass in healthy young adults: relation with gender and body size. Int J Card Imaging. 1999;15(5):411–9.

Sandstede J, Lipke C, Beer M, et al. Age- and gender-specific differences in left and right ventricular cardiac function and mass determined by cine magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol. 2000;10(3):438–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003300050072.

Alfakih K, Plein S, Thiele H, Jones T, Ridgway JP, Sivananthan MU. Normal human left and right ventricular dimensions for MRI as assessed by turbo gradient echo and steady-state free precession imaging sequences. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17(3):323–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.10262.

Chang SA, Choe YH, Jang SY, Kim SM, Lee SC, Oh JK. Assessment of left and right ventricular parameters in healthy Korean volunteers using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: change in ventricular volume and function based on age, gender and body surface area. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28(Suppl 2):141–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-012-0150-1.

Kawel-Boehm N, Maceira A, Valsangiacomo-Buechel ER, et al. Normal values for cardiovascular magnetic resonance in adults and children. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-015-0111-7.

Petersen SE, Aung N, Sanghvi MM, et al. Reference ranges for cardiac structure and function using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) in Caucasians from the UK Biobank population cohort. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-017-0327-9.

Le Ven F, Bibeau K, De Larochelliere E, et al. Cardiac morphology and function reference values derived from a large subset of healthy young Caucasian adults by magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(9):981–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jev217.

Le TT, Tan RS, De Deyn M, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance reference ranges for the heart and aorta in Chinese at 3T. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-016-0236-3.

Riffel JH, Schmucker K, Andre F, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance of cardiac morphology and function: impact of different strategies of contour drawing and indexing. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019;108(4):411–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-018-1371-7.

Anand SS, Tu JV, Awadalla P, et al. Rationale, design, and methods for Canadian alliance for healthy hearts and minds cohort study (CAHHM) - a Pan Canadian cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:650. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3310-8.

Zareian M, Ciuffo L, Habibi M, et al. Left atrial structure and functional quantitation using cardiovascular magnetic resonance and multimodality tissue tracking: validation and reproducibility assessment. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-015-0152-y.

Bonett DG. Sample size requirements for estimating intraclass correlations with desired precision. Stat Med. 2002;21(9):1331–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1108.

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420–8. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420.

Eliasziw M, Young SL, Woodbury MG, Fryday-Field K. Statistical methodology for the concurrent assessment of interrater and intrarater reliability: using goniometric measurements as an example. Physica Ther. 1994;74(8):777–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/74.8.777.

Maceira AM, Prasad SK, Khan M, Pennell DJ. Normalized left ventricular systolic and diastolic function by steady state free precession cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8(3):417–26.

Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(1):1-39.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003.

Ng ACT, Bax JJ. Hyperdynamic left ventricular function and the prognostic implications for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz706.

Wehner GJ, Jing L, Haggerty CM, et al. Routinely reported ejection fraction and mortality in clinical practice: where does the nadir of risk lie? Eur Heart J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz550.

Natori S, Lai S, Finn JP, et al. Cardiovascular function in multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: normal values by age, sex, and ethnicity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(6 Suppl 2):S357–65. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.04.1868.

Lei X, Liu H, Han Y, et al. Reference values of cardiac ventricular structure and function by steady-state free-procession MRI at 3.0T in healthy adult chinese volunteers. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45(6):1684–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25520.

Schulz-Menger J, Bluemke DA, Bremerich J, et al. Standardized image interpretation and post-processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance - 2020 update : Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR): Board of Trustees Task Force on Standardized Post-Processing. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2020;22(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-020-00610-6.

Kozor R, Callaghan F, Tchan M, Hamilton-Craig C, Figtree GA, Grieve SM. A disproportionate contribution of papillary muscles and trabeculations to total left ventricular mass makes choice of cardiovascular magnetic resonance analysis technique critical in Fabry disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-015-0114-4.

Higgins CB, Roos Ad. MRI and CT of the cardiovascular system. 3rd ed. ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013:chap Chapter 6: Quantification in Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography.

Hudsmith LE, Petersen SE, Francis JM, Robson MD, Neubauer S. Normal human left and right ventricular and left atrial dimensions using steady state free precession magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2005;7(5):775–82.

Childs H, Ma L, Ma M, et al. Comparison of long and short axis quantification of left ventricular volume parameters by cardiovascular magnetic resonance, with ex-vivo validation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429x-13-40.

Farber NJ, Reddy ST, Doyle M, et al. Ex vivo cardiovascular magnetic resonance measurements of right and left ventricular mass compared with direct mass measurement in excised hearts after transplantation: a first human SSFP comparison. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-014-0074-0.

Petersen SE, Matthews PM, Bamberg F, et al. Imaging in population science: cardiovascular magnetic resonance in 100,000 participants of UK Biobank - rationale, challenges and approaches. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429x-15-46.

Schulz-Menger J, Bluemke DA, Bremerich J, et al. Standardized image interpretation and post processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance: Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) board of trustees task force on standardized post processing. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429x-15-35.

de Simone G, Devereux RB, Daniels SR, Meyer RA. Gender differences in left ventricular growth. Hypertension. 1995;26(6 Pt 1):979–83. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.26.6.979.

Chung AK, Das SR, Leonard D, et al. Women have higher left ventricular ejection fractions than men independent of differences in left ventricular volume: the Dallas Heart Study. Circulation. 2006;113(12):1597–604. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.105.574400.

Acknowledgements

Steering Committee: S. Anand (Chair)*, M.G. Friedrich (Co-Chair), J. Tu (Co-Chair), P Awadalla (OHS), T. Dummer (BCGP), J. Vena (ATP), P. Broet (CaG), J. Hicks (APATH), J-C. Tardif (MHI Biobank), K. Teo (PURE-Central), B-M. Knoppers (ELSI). Project Office Staff at Population Health Research Institute (PHRI): D. Desai, S. Nandakumar (Ex), M. Thomas (Ex), S. Zafar. Statistics/Biometrics Programmers Team at PHRI: K. Schulze, L. Dyal, A. Casanova, S. Bangdiwala, C. Ramasundarahettige, K. Ramakrishnana, Q. Ibrahim. Central Operations Leads: D. Desai (PHRI), H. Truchon (Montreal Heart Institute), N. Tusevljak (Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences). Cohort Operations Research Personnel: K McDonald (OHS), N. Noisel (CaG), J. Chu (BCGP), J. Hicks (APATH), H. Whelan (ATP), S. Rangarajan (PURE), D. Busseuil (MHI Biobank). Site Investigators and Staff: (112) J. Leipsic, S. Lear, V. de Jong; (306) M. Noseworthy, K. Teo, E. Ramezani, N. Konyer; (402) P. Poirier, A-S. Bourlaud, E. Larose, K. Bibeau; (512) J. Leipsic, S. Lear, V. de Jong; (609) E. Smith, R. Frayne, A. Charlton, R Sekhon; (703) A. Moody, V. Thayalasuthan; (704) A. Kripalani, G Leung; (706) M. Noseworthy, S. Anand, R. de Souza, N. Konyer, S. Zafar; (707) G. Paraga, L. Reid; (714) A. Dick, F. Ahmad; (799) D. Kelton, H. Shah; (801) F. Marcotte, H. Poiffaut; (802) M. Friedrich, J. Lebel; (817) E. Larose, K. Bibeau; (913) R. Miller, L. Parker, D. Thompson, J. Hicks; (1001) J-C. Tardif, H. Poiffaut; (1103) J. Tu, K. Chan, A. Moody, V. Thayalasuthan; MRI Working Group and Core Lab Investigators/Staff: Chair: M.G. Friedrich; Brain Core Lab: E. Smith, C. McCreary, S. E. Black, C. Scott, S. Batool, F. Gao; Carotid Core Lab: A. Moody, V. Thayalasuthan; Abdomen: E. Larose, K. Bibeau, Cardiac: F. Marcotte, F. Henriques, T. Teixeira. Contextual Working Group: R. de Souza, S. Anand, G. Booth, J. Brook, D. Corsi, L. Gauvin, S. Lear, F. Razak, S.V. Subramanian, J. Tu. CAHHM Founding Advisory Group: Jean Rouleau, Pierre Boyle, Caroline Wong, Eldon Smith. CAHHM Scientific Review Board: Bob Reid, Ian Janssen, Amy Subar, Rhian Touyz

Funding

CAHHM was funded by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSF-Canada), and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Financial contributions were also received from the Population Health Research Institute and CIHR Foundation Grant no. FDN-143255 to S.S.A.; FDN-143313 to J.V.T.; and FDN 154317 to E.E.S. In-kind contributions from A.R.M. and S.E.B. from Sunnybrook Hospital, Toronto for CMR reading costs, and Bayer AG for provision of IV contrast. The Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow Project is funded by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, BC Cancer Foundation, Genome Quebec, Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and Alberta Health and the Alberta Cancer Prevention Legacy Fund, Alberta Cancer Foundation. The PURE Study was funded by multiple sources. The Montreal Heart Institute Biobank is funded by Mr André Desmarais and Mrs France Chrétien-Desmarais and the Montreal Heart Institute Foundation. S.S.A. was supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Ethnicity and Cardiovascular Disease and Heart and Stroke Foundation Chair in Population Health. P.A. was supported by a Ministry of Research and Innovation of Ontario Investigator Award. S.E.B. was supported by the Hurvitz Brain Sciences Research Program, Sunnybrook Research Institute, and the Department of Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto. E.L. was supported by the Laval University Chair of Research & Innovation in Cardiovascular Imaging and the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé. J.-C.T. holds the Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in translational and personalized medicine and the Université de Montréal Pfizer endowed research chair in atherosclerosis. Some of the data used in this research were made available by the Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow Project along with BC Generations Project, Alberta’s tomorrow Project, Ontario Health Study, CARTaGENE, and the Atlantic PATH. Data were harmonized by Maelstrom and access policies and procedures were developed by the Centre of Genomics and Policy in collaboration with the Cohorts.

CG is supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF, # PP00P3_163892 and # PP00P3_190074), the Olga Mayenfisch Foundation, Switzerland, the OPO Foundation, Switzerland, the Novartis Foundation, Switzerland, the Swissheart Foundation, the Helmut Horten Foundation, Switzerland, the University Hospital Zurich (USZ) Foundation, the Iten-Kohaut Foundation, Switzerland, and the EMDO Foundation, Switzerland. Dr. Anand holds the Heart and Stroke Foundation Michael G DeGrooote Chair in Population Health and a Canada Research Chair in Ethnic Diversity and Cardiovascular Disease.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JL and CG contributed to all aspects of the manuscript. DD contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and revising of the manuscript. CR and KS contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript revision. PA and PB contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, and manuscript revision. FM, TD, JH, and EL contributed to the design, data acquisition and interpretation, and manuscript revision. AM, ES, JCT, KT, JV, DL, SA, and MF contributed to the design, data acquisition, and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research ethics approval was granted by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board, with consent obtained at each collaborating site as per site-specific regulations prior to participation in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The University Hospital Zurich (CG) holds a research contract with GE Healthcare. Matthias G. Friedrich is board member, shareholder, and consultant of Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Flow chartfor patient selection. RI, magnetic resonance imaging; LVEF, leftventricular ejection fraction; LV mass, left ventricular mass; CVD,cardiovascular disease; PURE, prospective urban and rural epidemiologicalstudy; CPTP, the Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow Project; BC Generations,British Columbia; OHS, Ontario Health Study; Atlantic PATH, AtlanticPartnership for Tomorrow's Health; MHI, Montreal Heart Institute. Figure S2. Age-specific trends for males and females for A) LV end-systolic volumesindexed to BSA (ml/m2); B) LV end-diastolic volumes indexed to BSA(ml/m2); and C) LVEF (%). Linear regression was applied to model the data,which are presented as mean (blue lines) and 95% confidence intervals (redlines). Figure S3. Representativeexamples of Bland Altman plots for inter-observer variability of absolute leftand right ventricular stroke volumes (ml). Figure S4. Representativeexamples of Bland Altman plots for intra-observer variability of absolute leftand right ventricular stroke volumes (ml).

Additional file 2: Table S1a.

Biventricular and left atrial absolute reference valuesfor healthy males (n=1126) and females (2080). Values reported as mean±SDwith 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S1b. Biventricular and left atrialreference values indexed to height for healthy males (n=1126)and females (2080). Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidenceintervals and normal ranges. Table S2a. Biventricular and left atrialabsolute reference values for males 35 to 75 years, stratifiedby 10–year age categories. Values reported as mean±SDwith normal ranges. Table S2b. Biventricular and left atrial reference values indexedto height for males 35 to 75 years, stratified by 10–year agecategories. Values reported as mean±SD with normal ranges. Table S3a. Biventricular and left atrial absolute referencevalues for females 35 to 75 years, stratified by 10–yearage categories. Values reported as mean±SDwith normal ranges. Table S3b. Biventricular and left atrial reference values indexedto height for females 35 to 75 years, stratified by 10–yearage categories. Values reported as mean±SDwith normal ranges. Table S4a. Biventricular and atrial absolute reference values for healthy males (n=861) and females (1604) for white Caucasiansonly. Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S4b. Biventricular and left atrial reference values index toheight for healthy males (n=861) and females (1604) for white Caucasiansonly. Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S4c. Biventricular and atrial reference values indexed to BSAfor healthy males (n=861) and females (1604) for white Caucasiansonly. Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S5a. Biventricular and left atrial absolute reference valuesfor healthy males (n=191) and females (356) for Chinese only.Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S5b. Biventricular and left atrial reference values indexed toheight for healthy males (n=193) and females (356) for Chinese only.Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S5c Biventricular and left atrial reference values indexed toBSA for healthy males (n=193) and females (356) for Chinese only.Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S6a. Biventricular and left atrial absolute reference valuesfor healthy males (n=53) and females (70) for South Asians only.Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S6b. Biventricular and atrial reference values indexed to heightfor healthy males (n=53) and females (70) for South Asians only.Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges. Table S6c. Biventricular and atrial reference values indexed to BSAfor healthy males (n=53) and females (70) for South Asians only.Values reported as mean±SD with 95% confidence intervals and normal ranges.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Luu, J.M., Gebhard, C., Ramasundarahettige, C. et al. Normal sex and age-specific parameters in a multi-ethnic population: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance study of the Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds cohort. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 24, 2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-021-00819-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-021-00819-z