Abstract

Background

Syndecan-1 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan acting as a co-receptor for cytokines and growth factors mediating developmental, immunological and angiogenic processes. In human, the uteroplacental localization of Syndecan-1 and its reduced expression in pregnancy-associated pathologies, such as the intrauterine growth restriction, suggests an influence of Syndecan-1 in embryo-maternal interactions. The aim of the present study was to identify the effect of a reduced expression of Syndecan-1 on the reproductive phenotype of mice and their progenies.

Methods

Reproductive characteristics have been investigated using animals with reduced Syndecan-1 and their wildtype controls after normal mating and after vice versa embryo transfers. Female mice were used to measure the estrus cycle length and the weight gain during pregnancy, as well as for histological examination of ovaries. Male mice were examined for the concentration, motility, viability and morphology of spermatozoa. Organs like heart, lung, liver, kidney, spleen, brain and ovaries or testes and epididymis of 6-month-old animals were isolated and weighed. Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed students t-test with P < .05 and P < .02, chi square test (P < .05) and Fisher’s Exact Test (P < .05). A linear and a non-linear mixed-effects model were generated to analyze the weight gain of pregnant females and of the progenies.

Results

Focusing on the pregnancy outcome, the Syndecan-1 reduced females gave birth to larger litters. However, regarding the survival of the offspring, a higher percentage of pups with less Syndecan-1 died during the first postnatal days. Even though the ovaries and the testes of Syndecan-1 reduced mice showed no histological differences and the ovaries showed a similar number of primary and secondary follicles and corpora lutea, the spermatozoa of Syndecan-1 reduced males showed more tail and midpiece deficiencies. Concerning the postnatal and juvenile development the pups with reduced Syndecan-1 expression remained lighter and smaller regardless whether carried by mothers with reduced Syndecan-1 or wildtype foster mothers. With respect to anatomical differences kidneys of both genders as well as testes and epididymis of male mice with reduced syndecan-1 expression weighed less compared to controls.

Conclusions

These data reveal that the effects of Syndecan-1 reduction are rather genotype- than parental-dependent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans (PGs) are ubiquitous frequent glycoproteins with one or more HS chain/s that can bind cytokines and growth factors and hence generate gradients influencing developmental, immunological and angiogenic processes [1]. Syndecans (SDCs) belong to the well-studied family of HSPGs which consists of 4 genes (Sdc1 to 4) [1]. So far, Sdc1−/− knock-out (KO) mouse models revealed the participation of SDC1 in cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis [2, 3], as well as in angiogenesis [4].

The present study focuses on the reproductive phenotype of heterozygous Sdc1+/− mice, as studies from our group previously showed the involvement of SDC1 at the embryo-maternal interface in vitro regulating the secretion of chemokines and angiogenic factors during decidualization, implantation and implantation-associated apoptosis in human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells [5,6,7]. SDC1 has been shown to be expressed in the human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle [8] and could be associated with numerous human pregnancy pathologies based upon an insufficient implantation process. The reduced placental expression of SDC1 could be correlated with intrauterine growth restriction [9], preeclampsia [10], and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome [11], whereas elevated placental SDC1 expression reduced the risk for preterm birth [12].

Even though the Sdc1 mouse model is widely used in animal research, the reproductive phenotype has not been investigated, yet. In general, the characteristics of the remarkably short reproductive period and parturition interval render the mouse a valuable tool for studying the reproductive phenotype [13]. Mice have a short window for embryo implantation [14, 15], that lasts less than 24 h, a time frame that reduces the chances of a successful implantation in case of targeted mating. Therefore, many studies tried to establish an identification system for the estrous cycle phases [16] until Stockard and Papanicolaou developed a histological examination focusing on vaginal cells [17] including epithelial cells, cornified cells and leukocytes [18, 19].

The aim of the present study was to examine the reproductive phenotype of the Sdc1+/− mouse, since for practical and ethical reasons the in vivo examination in human is not possible during an ongoing pregnancy. We focused on heterozygous Sdc1+/− mice with a reduced concentration of SDC1 instead of Sdc1−/− mice because a downregulation may reflect a possible dysregulation in human more closely rather than a complete absence of SDC1, which can be expected to be a rare event. Concentrating on reproductive characteristics, the ovaries, testes and germline cells were examined followed by pregnancy characteristics after normal mating and after vice versa embryo transfers. Consecutively the offspring with respect to viability and weight gain from birth to adolescence have been studied because a potential slow postnatal growth due to a possibly reduced lactation was of interest, as it has been described in the literature, that animals with a complete knock out of SDC1 present an impaired mammary ductal development [3]. Therefore, the individual reproductive characteristics of the Sdc1+/− mouse compared to WT mouse were investigated to reveal if the origin of the SDC1 effect is of embryonic, maternal and/or paternal source.

Methods

Animals

Planning and conduction of the experimental procedures as well as maintenance of the animals was carried out in accordance to the German Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory animals after they were approved by the State Office for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection (LANUV, State of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany). Mice were maintained at 20–24 °C on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with food (ssniff Spezialdiäten GmbH, Soest, Germany) and water ad libitum. Sdc1 KO (Sdc1−/−) mice were originally generated on a C57BL/6J background, C57BL/6J.129Sv-Sdc1tm12MB [20] by completely backcrossing for 10 generations.

Quantification of SDC1 expression

Tail biopsies were genotyped according to the FELASA guidelines [21]. For the quantitative measurement of SDC1 the mouse SDC1 ELISA Kit (biorbyt, San Francisco, California, USA) was applied. Tail biopsies from 15 Sdc1−/−, 17 Sdc1+/− and 50 WT mice were homogenized and lysed in tissue lysis buffer (0.5% (v/v) octylphenoxypolyethoxyethanol, 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany) and 100 μl of the homogenate was used to perform the ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Furthermore, 1 μl of the homogenate was used for whole protein quantification via BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) to normalize the amount of SDC1.

Detection of estrous cycle and breeding characteristics

Vaginal smears from 8-weeks-old females of both Sdc1+/− (n = 29) and WT (n = 34) groups were extracted daily for 12 days at the same time [22] and observed under the microscope (Carl Zeiss Fixed Stage Standard Microscope, 10x Objective, Oberkochen, Germany). The proportion of nucleated epithelial cells, cornified squamous epithelial cells and leukocytes was counted [22].

The duration of pregnancy and the weight gain during pregnancy were constantly studied with a particular number of females: 6 Sdc1+/− females and 4 controls in single matings and 5 Sdc1+/− and 5 WT females which were mated individually and continuously for a period of 4 months. The weight (Dipse digital scale TP500, Oldenburg, Germany) of the pregnant Sdc1+/− and control females was monitored the day before mating, indicated as the day before the presence of a vaginal plug (day 0), as well as on day 4, 8, 12, 16, 18 after mating and then every day until birth.

Organ isolation

The progeny of both groups was weighed directly after birth, then every 3 days until the 60th day and subsequently once in 10 days until day 200. The following organs of 200-days-old male and female Sdc1+/− and WT mice have been weighed: heart, lung, liver, kidney, spleen and brain (Mettler Toledo AE50, Dorsten, Germany). For the selective examination of implantation sites, uteri from 8-week-old females (Sdc1+/− and WT, each 30 animals) at embryonic day 6 of pregnancy were extracted. Additionally, ovaries were isolated and fixed in formalin for further histological hematoxylin and eosin examination [23]. Three investigators assessed the number and morphology of the primary and secondary/tertiary follicles. Both testes and epididymis of 6-month-old males were assessed for sperm analysis (Sdc1+/−/WT males: n = 28/24). The caput and corpus epididymis were weighed together, the cauda alone. Paired organs were weighed separately and the mean value was calculated. Additional animals were used for the weighing of adults organs apart from the ones that were weighed up to day 200 so those in totals a minimum of 49 animals were examined.

From the vice versa embryo transfers (see below) the organs of 8 Sdc1+/− males, 6 Sdc1+/− females, 3 WT males and 5 WT females were also isolated and weighed (Mettler Toledo AE50, Dorsten, Germany).

Organ to body weight ratios were calculated and were considered more useful because of the body weight differences [24,25,26].

Embryo transfer

Female mice were intraperitoneally superovulated using 5 IU PMSG (Intergonan® 240 IE/ml, MSD Tiergesundheit, Unterschleißheim, Germany) and 5 IU hCG (Predalon® 5000 IE, Essex Pharma GmbH, Waltrop, Germany) 48 h later, followed by mating [27]. On day 1.5 after HCG administration, egg donors were sacrificed, their oviducts extracted and the embryos at the 2-cell stage flushed using M2 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany). An average number of 12 2-cell embryos were transferred in the oviduct of pseudopregnant recipient foster mothers [27] of the opposite mouse line (Sdc1+/− embryos into 4 WT and WT embryos into 3 Sdc1+/− recipients). Pups from these vice versa embryo transfers were monitored as mentioned above until day 200 (Sdc1+/− males: n = 8, Sdc1+/− females: n = 6; WT males: n = 3, WT females: n = 5).

Male reproductive characteristics

Adult non-breeder males (Sdc1+/−: n = 28; WT: n = 24) were euthanized, the anogenital distances measured [28], and the cauda, corpus, caput epididymis and testes isolated and weighed. The testes and the caput-corpus epididymis were fixed in Bouin’s solution (RAL Diagnostics, Martillac, France) for immunohistochemical analysis [23], whereas the cauda epididymis were placed into 2 ml hypertonic saline buffer [29] in a 35 mm culture dish. The epididymis were minced and the sperm were allowed to swim out of the tissue by incubating the dish in a 37 °C incubator (MCO-5 AC, Sanyo, Eschborn, Germany). After 30 min the suspension was centrifuged (Universal 320R centrifuge, Hettich, Vlotho, Germany) for 5 min at 0.1 rcf (relative centrifugal force) and the precipitate used for further analysis. Two independent investigators assessed the histology of the testes and the sperm concentration, viability and morphology by microscopical examination. The number of motile and immotile sperm cells was counted twice using a disposable Makler counting chamber (CV 1010–102, Cell Vision, Heerhugowaard, The Netherlands) under a light microscope (Carl Zeiss Fixed Stage Standard Microscope, 10x Carl Zeiss Objective, Oberkochen, Germany).

Regarding sperm viability, the number of viable and nonviable spermatozoa was counted after staining in 0.5% eosin solution twice in a Neubauer counting chamber (Fast Read 102®, Biosigma S.r.l., Cona, Italy) under a light microscope (Carl Zeiss Fixed Stage Standard Microscope, 40x Carl Zeiss Objective). Sperm morphology was determined after staining using the SpermacStain® kit (FertiPro N.V., Beernem, Belgium) according to manufacturer’s instructions and the literature [30]. The percentage of normal, head-, acrosome- and tail-defective spermatozoa in a total of 100 cells was calculated twice for the air-dried smears under a Carl Zeiss Fixed Stage Standard Microscope by two independent investigators (Neofluar 100x Carl Zeiss Oil Objective).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed student’s t-test (P < 0.05) for the number of implantation sites, born and dead pups, litter sizes, organ weights and anogenital distances. The two-tailed t-test with Bonferroni adjustment (P < 0.02) was applied to compare the SDC1 amount in Sdc1−/−, Sdc1+/− and WT animals, the weight of the mice at day 0, 33 and 60 of their development, chi square test (P < 0.05) for sperm analysis and Fisher’s Exact Test (P < 0.05) for the mouse cycle data. Results are depicted as mean ± S.E.M. A linear mixed-effects model was generated to analyze the weight gain of pregnant females (R statistical package, Version 3.3.2.). Included predictors were observation days, mouse line (Sdc1+/−, WT) and the interaction between time and mouse line (P < 0.05). The correlation coefficient Spearman’s Rho (ρ) was employed for weight gain depending on litter size. Concerning the weight measurements of the progeny from day 0 to 200 a nonlinear mixed-effects model (weighing curves, R statistical package, Version 3.2.4, lme4 packet for linear mixed-effects models, Lattice packet for the graphics) [31] with the form y = α − β ∗ γx was applied. The fixed effects are the group effects (Sdc1+/−, WT, mother/foster) for each parameter α, ß and γ of the nonlinear curve. Random effect components were defined as the deviations of individual parameters with respect to the average of the corresponding group. The y-value represents mouse weight at a certain time point x-value in the development of the mouse. α indicates the maximum possible weight, ß the difference between the maximum and starting weight. γ is growth rate specific for each animal or group. Thus, the growth development of the Sdc1+/− and WT mice is calculated from the maximum weight α and the growth rate ßγx according to the formula given. The level of significance for each variable is given at each table in the results part and the combination of the 3 variables gives the overall level of significance (P < 0.05).

Results

Proof of the SDC1 reduction

Quantitative measurement of SDC1 revealed that Sdc1+/− mice had 60% less amount of protein in comparison to the WT mice (Fig. 1, P < 0.01). This difference was independent from gender and age.

Mouse cycle

Physiologically, the estrous stages are: pro- (P), estrus (E), met- (M) and diestrus (D). The first cycle for each female started with the actual cycle day of sampling and was completed with M or D after an E.

Sexual mature females of the Sdc1+/− and WT group had an average number of 1.79 ± 0.11 and 1.91 ± 0.09 cycles respectively. Eight Sdc1+/− and 6 WT females underwent only 1 cycle, 18 Sdc1+/− and 24 WT females showed 2 cycles and 2 Sdc1+/− and 3 WT had 3 cycles. In Table 1 an overview of the sequential arrangement of each stage per cycle is depicted (1–6 days). For the Sdc1+/− and WT group, the average cycle duration was 5.02 ± 0.19 and 4.59 ± 0.15 days respectively 48% of the Sdc1+/− and 40% of the WT mice underwent a 4-day cycle, 16% of Sdc1+/− and 37% of WT a 5-day (P < 0.05) and finally, 24% of Sdc1+/− and 3% of WT females had a cycle of 6 days (P < 0.05). A representative cycle of a Sdc1+/− and a WT female is depicted in Fig. 2.

Concerning the observed irregular cycles (6 for the Sdc1+/− and 5 for the WT group), 3 Sdc1+/− females showed 3 cycles in absence of E, 2 cycles without P and only 1 that showed no M. On the contrary, for the WT females there was only 1 female with no E stage and all other 4 showed unterminated E cycles with no M and/or D stage after only 1 or more days of E.

Characteristics of the female reproductive phenotype and the progeny

30 females of each group showed a vaginal plug after mating and 53% of the Sdc1+/− and 47% of the WT females showed implantation sites on embryonic day 6 with an average number of 8.00 ± 0.45 for the Sdc1+/− and 7.29 ± 0.53 for WT. The histological examination of the ovaries revealed no significant differences for the number of either primary, secondary or tertiary follicles or corpora lutea (data not shown).

The duration of pregnancy for the Sdc1+/− and the WT females in the breeding setting was for the Sdc1+/− 20.68 ± 0.47 and WT 20.89 ± 0.56 days with a range of 18 to 26 days. The statistically different mean initial weight (day 0) of Sdc1+/− and WT females was 24.37 ± 0.83 g vs. 26.95 ± 0.98 g respectively (P < 0.05). During the course of pregnancy the Sdc1+/− females gained 15.05 ± 0.53 g on average and gave birth to 7.36 ± 0.40 pups. The minimum weight gain was 9.65 g with a litter size of 5 and the maximum was 21.10 g with 10 pups born. The WT females gained 16.37 ± 0.88 g on average during pregnancy and gave birth to 6.37 ± 0.58 pups. The minimum weight gain was 8.70 g (3 pups) and the maximum 23.35 g (10 pups).

Regarding the course of pregnancy the WT females were heavier than the Sdc1+/− females with a comparable weight gain per day (Fig. 3).

In case of consecutive litters, a moderate Spearman’s Rho correlation coefficiency (ρ = 0.53) between the litter size and the weight gain was found for the Sdc1+/− group and a very strong association for the controls (ρ = 0.81).

Focusing on the development of the progenies, a total of 193 Sdc1+/− pups (25 litters) and 151 WT pups (23 litters) were born (Fig. 4a). 107 Sdc1+/− (55%) and 101 WT (67%) mice survived and were monitored for 200 days. Statistically significant more Sdc1+/− newborns died compared to WT (45% vs. 33%). The majority of pups died during the first 3 days after birth (Fig. 4b). However, the death pace between the two groups was almost the same (Fig. 4b). Reaching weaning age, 57% Sdc1+/− males and 43% Sdc1+/− females as well as 45% WT males and 55% WT females were separated.

Observation of pregnancy outcome after mating. a Total number (25 SDC-reduced litters, 193 born pups, 23 WT litters: 151 born pups) of juveniles before and after gender determination and weaning (statistical significance between the numbers of dead juveniles of the two groups is indicated with an asterisk (P < 0.05; two-tailed t-test)). b Subdivision according to the day of death. The curves above the columns describe the sinusoidal death pace from day one to 6 and later. c Mean litter size before and after gender determination excluding the dead pups

On the day of birth, the Sdc1+/− pups were significantly lighter (1.24 ± 0.01 g) than the WT pups (1.33 ± 0.01 g) (P < 0.001). From the day of gender determination (day 21) up to adolescence (day 200) the Sdc1+/− male and female mice were 7 and 9% lighter than the WT controls respectively Single important time points during development have been selected: sexual maturity on day 33 (Sdc1+/− males 17.10 ± 0.19 g and Sdc1+/− females 14.58 ± 0.15 g, WT males 18.34 ± 0.38 g and WT females 15.52 ± 0.26 g) and breeding maturity on day 60 (Sdc1+/− males 23.97 ± 0.15 g and Sdc1+/− females 18.68 ± 0.21 g, WT males 26.00 ± 0.30 g and WT females 20.31 ± 0.23 g). At both time points, the weight difference was significantly different (P < 0.005). The weight gain of the mice during their development and the growth curves between the Sdc1+/− and the WT control group are shown in Fig. 5a with the associated parameters (Fig. 5b). The obtained weight data displayed by the curves were also significantly different for the whole monitoring period. No significant differences in the shape and the course of the weight curves were observed. The weight of the WT mice was found in accordance with commercial breeders [32].

Weight curves of Sdc1+/− and WT pups using a nonlinear mixed-effects model. a Weight is separated by gender and by mouse type as indicated with different colors observed until day 200. b Model for comparison of the Sdc1+/− vs WT mice. The alpha (α), beta (ß) and gamma (γ) effects of the y = α − β ∗ γx equation for the nonlinear mixed-effects model are given with the confidence intervals and the statistical significances (**P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01)

Organ weight

Organs from at least 49 Sdc1+/− and WT mice were isolated and weighed on day 200. The body weight of both Sdc1+/− and WT males and females was significantly different (P < 0.005) (Sdc1+/−/WT males: 29.61 ± 0.25 g/31.61 ± 0.37 g; Sdc1+/−/WT females: 24.10 ± 0.27 g/25.37 ± 0.26 g). The relative values of organ weight per body weight (Fig. 6) displayed lighter kidneys and heavier hearts and lungs in the Sdc1+/− females and lighter kidneys, testes and epididymis in Sdc1+/− males.

Vice versa experiment

From the vice versa embryo transfer of Sdc1+/− and WT embryos a total of 19 Sdc1+/− and 12 WT pups resulted, from which 26% Sdc1+/−and 33% WT died within the first days. Reaching weaning age, 57% Sdc1+/− males and 43% Sdc1+/− females as well as 38% WT males and 63% WT females were separated from their mothers.

The average duration of pregnancy for Sdc1+/− foster mothers was 22.5 days (20–24 days) and for WT females 20 days (19–22 days). The Sdc1+/− foster mothers gained 11.85 ± 2.34 g on average with an average number of 6 pups born. The WT foster mothers gained 13.35 ± 1.94 g on average and gave birth to an average number of 5 pups. The minimum weight gain was 9.6 g, when 6 pups were born and the maximum 17.65 g (7 pups born).

On the day of birth, the Sdc1+/− pups were lighter (1.38 ± 0.04 g) than the WT pups (1.47 ± 0.05 g). In the course of growth the Sdc1+/− male and female mice were 16 and 14% lighter than the WT mice respectively. On the 2 important time points, day 33 and 60, the weight differences were significantly different (day 33: Sdc1+/− males 17.28 ± 1.06 g and Sdc1+/− females 15.36 ± 0.53 g, WT males 22.68 ± 0.29 g and WT females 17.73 ± 0.50 g, day 60: Sdc1+/− males 24.12 ± 0.31 g, Sdc1+/− females 19.44 ± 0.36 g, WT males 28.47 ± 1.19 g and WT females 22.54 ± 0.38 g, P < 0.02).

The weight gain of the vice versa mice during their development and the growth curves are displayed in Fig. 7a with significant differences (Fig. 7b). In contrast to the females, it was not possible to generate a model for the weight data of the male group, because only a few male pups were born.

Weight curves of the Sdc1+/− and WT pups after vice versa embryo transfer. a The weight is separated by gender and by mouse type as indicated with different colors calculated with a nonlinear mixed-effects model. b Comparison of the Sdc1+/− vs WT mice carried by a WT or a Sdc1+/− mother respectively. The alpha (α), beta (ß) and gamma (γ) effects of the y = α − β ∗ γx equation for the nonlinear mixed-effects model are given with the confidence intervals and the statistical significances (**P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01)

At the age of 6 month the organs from the vice versa animals were isolated and weighed. Sdc1+/− male and female mice carried by a WT mother were significantly lighter than the WT animals that were carried by a Sdc1+/− mother (Sdc1+/−/WT males: 29.33 ± 0.36 g/34.13 ± 1.22 g; Sdc1+/−/WT females: 23.18 ± 0.24 g/26.98 ± 0.39 g) (P < 0.005). Sdc1+/− females had significant lighter kidneys and significant heavier uteri (Fig. 8).

Organ per body weight after vice versa embryo transfers. Data are shown for female (a) and male (b) Sdc1+/− and WT mice. Organs were isolated from all vice versa progenies (Sdc1+/− males: n = 8, Sdc1+/− females: n = 6; WT males: n = 3, WT females: n = 5). Significant organ weight differences are indicated with an asterisk (P < 0.05; two-tailed t-test)

Male reproductive characteristics

The anogenital distance showed no difference (19 vs. 20 mm). The relative weight of Sdc1+/− vs. WT testis and caput-corpus per body weight was significantly different (P < 0.001), whereas the cauda showed no difference (Fig. 6). Histological examination of the testes also did not reveal any differences (data not shown). The sperm concentration of motile and non-motile spermatozoa did not differ, however a higher percentage of motile spermatozoa existed in the Sdc1+/− males. The percentage of vital and dead sperm also did not differ (Table 2).

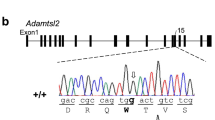

Concerning the morphology, the spermatozoa of the Sdc1+/− males demonstrated a higher number of abnormalities compared to WT. The Sdc1+/− spermatozoa had more midpiece and tail abnormalities, whereas the WT spermatozoa showed more head-acrosome deficiencies (Fig. 9a, b).

Comparison of the sperm abnormalities observed between Sdc1+/− and WT males. a Spermatozoa with head-acrosome-, midpiece- and tail-deficiencies were observed opposed to the normal ones. Spermatozoa with more than one defect were not assigned to one of these categories (Sdc1+/−/WT males: n = 28/24; all mice sexually matured: 6–12 months; technical repeats: n = 2; number of spermatozoa counted: n = 100; P < 0.05; chi square test). b-e Representative photos of the observed abnormalities (bar = 8 μm, normal spermatozoon (b), spermatozoon with head (c), acrosome (d) or tail (e) defect)

Discussion

The importance of the SDC1 protein and its involvement in human pregnancy associated pathologies in human elucidates the necessity of using a suitable animal model. The individual analysis of the different maternal and paternal reproductive characteristics was performed in Sdc1+/− mice to enlighten the reproductive phenotype taking into account that a complete loss of SDC1 seems to be unlikely in human.

Selected findings are discussed further in the following paragraphs:

Mouse cycle

An easy-to-interpret marker in mouse breeding is the vaginal estrous cycle, which can be predicted through changes in the morphology and content of vaginal cells [33]. The objective of the estrous cycle monitoring was to determine the influence of the reduced expression of SDC1 on cycle frequency and length, as studies on selected lines examined for fecundity revealed a correlation between cyclicity and reproductive performance [34].

The estrous cycle for Sdc1+/− and WT mice lasted 5 days on average, which is in accordance with data from the literature [35] and the Mouse Genome Informatics Jackson Laboratory Database [36]. Interestingly, the WT females went through more complete regular cycles compared to Sdc1+/−. Correspondingly, a significant higher percentage of the Sdc1+/− females showed a 6 day long estrous cycle. Among the Sdc1+/− females, a significantly prolonged P stage was observed suggesting a delayed ovulation or a longer maturation of the ovarian follicles. During the E stage, the females are more receptive to males and copulation is more likely to happen. Although Sdc1+/− females showed less E stages, no impact on the pregnancy rate occurred.

Characteristics of the female reproductive phenotype and progeny

A former study on the role of the heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor showed that the HSPG may be beneficial for blastocyst endometrial interaction in mice [37]. The average duration of a pregnancy for both Sdc1+/− and WT females was in accordance to the Jackson Laboratory database (18 to 22 days).

Concerning litter sizes and therefore an indirect indicator for breeding quality, the sizes were in accordance to the MGI international database resource [38], but a significantly higher number of Sdc1+/− pups died postnatally within the first 7 days. A litter loss of 32% for C57BL/6 mice described in the literature is in accordance to our data for the WT animals [39]. Mammal pups depend on their mother for nutrition and the absence of lactation could lead to death [40]. Although the mammary glands of the Sdc1−/− females are hypomorphic [3], our vice versa experiment showed, that still 26% of the Sdc1+/− pups died when carried and nursed by a WT foster mother which rather hints to a genotype-association rather than a lactation problem. The lower number of postnatally dead pups from the vice versa setting led to the hypothesis that there might be an additive maternal effect though. Hence it is of great interest that former studies on Sdc1−/− mice revealed that these mice show symptoms of abnormal cold stress at normal housing temperatures and have an impaired intradermal adipocyte function [41]. These findings and the already proven importance of the brown adipocyte tissue for the survival of newborn pups [42] might rather explain the increased death rate of the Sdc1+/− pups.

In our study, the Sdc1+/− mice were systematically smaller, either when carried by a Sdc1+/− or a WT foster mother. In contrast to the females, it was not possible to generate a model for the weight data of the male group, because only a few male pups were born. It is worth mentioning here that both Sdc1+/− and WT mice showed a similar course of weight gain during the 200 days which is congruent to the literature for the WT mice [43].

Organ weight

The relative values of organ to body weight were calculated to erase a possible bias concerning the lighter body weight of the Sdc1+/−. The relative kidney weight of Sdc1+/− mice as well as Sdc1+/− females resulting from vice versa transfers was significantly lower than in the WT animals. Reduced SDC1 expression could influence epithelial-mesenchymal interaction being important for kidney morphogenesis [44] with a possible widespread impact on the kidney physiology since the kidney has been found to be a source considerably rich in SDC1 [45]. Possible alterations in the HS structure, as in the case of the 2-O-sulfotransferase-deficient embryos, may influence the binding of growth factors and morphogens that are important for kidney development [46]. Previous studies have shown an impaired renal function associated with a reduced tubular repair [47] possibly similar to SDC1’s role in dermal wound healing [20].

The mouse testes weight is directly correlated to male fertility, i.e., spermatogenic ability [48]. SDC1 could be associated to rat sertoli cell development [49] and maturation being a target and co-receptor of bFGF [50] suggesting a potential role for SDCs in spermatogenesis. The size and weight of the testes of WT males were in accordance to other mouse strains [51]. Intriguingly, the Sdc1+/− relative testis weight was significantly lower although the anogenital distance as a marker for male masculinization programming window during embryogenesis [52] showed no difference. The reproductive outcome observed by implantation sites and litter sizes of the Sdc1+/− mice was not impaired.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the reduced expression of SDC1 impairs the reproductive phenotype resulting in more postnatally dead pups and a genotype-related reduced body weight including some organs throughout the lifespan of the mice. Further studies need to elucidate the origin of the observations and therefore gaining more insight into the role of SDC1 in the hormonal axis, signaling pathways and cellular effects.

Abbreviations

- D:

-

Diestrus

- E:

-

Estrous

- EGF:

-

Epidermal growth factor

- HCG:

-

human chorionic gonadotrophin

- HELLP:

-

Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count

- HS:

-

Heparan sulfate

- KO:

-

Knock-out

- M:

-

Metestrus

- P:

-

Proestrus

- PG:

-

Proteoglycan

- PMSG:

-

Pregnant mare’s serum gonadotrophin

- Sdc1:

-

Syndecan-1

- WT:

-

Wild type

References

Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, et al. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–77.

Alexander CM, Reichsman F, Hinkes MT, Lincecum J, Becker KA, Cumberledge S, et al. Syndecan-1 is required for Wnt-1-induced mammary tumorigenesis in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):329–32.

Liu BY, Kim YC, Leatherberry V, Cowin P, Alexander CM. Mammary gland development requires syndecan-1 to create a beta-catenin/TCF-responsive mammary epithelial subpopulation. Oncogene. 2003;22(58):9243–53.

Teng YH, Aquino RS, Park PW. Molecular functions of syndecan-1 in disease. Matrix Biol. 2012;31(1):3–16.

Baston-Buest DM, Altergot-Ahmad O, Pour SJ, Krussel JS, Markert UR, Fehm TN, et al. Syndecan-1 acts as an important regulator of CXCL1 expression and cellular interaction of human endometrial stromal and trophoblast cells. Mediat Inflamm. 2017;2017:8379256.

Baston-Bust DM, Gotte M, Janni W, Krussel JS, Hess AP. Syndecan-1 knock-down in decidualized human endometrial stromal cells leads to significant changes in cytokine and angiogenic factor expression patterns. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:133.

Boeddeker SJ, Hess AP. The role of apoptosis in human embryo implantation. J Reprod Immunol. 2015;108:114–22.

Germeyer A, Klinkert MS, Huppertz AG, Clausmeyer S, Popovici RM, Strowitzki T, et al. Expression of syndecans, cell-cell interaction regulating heparan sulfate proteoglycans, within the human endometrium and their regulation throughout the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(3):657–63.

Chui A, Zainuddin N, Rajaraman G, Murthi P, Brennecke SP, Ignjatovic V, et al. Placental syndecan expression is altered in human idiopathic fetal growth restriction. Am J Path. 2012;180(2):693–702.

Heyer-Chauhan N, Ovbude IJ, Hills AA, Sullivan MH, Hills FA. Placental syndecan-1 and sulphated glycosaminoglycans are decreased in preeclampsia. J Perinat Med. 2014;42(3):329–38.

Norwitz ER. Defective implantation and placentation: laying the blueprint for pregnancy complications. Reprod BioMed Online 2007;14 Spec No 1:101–9.

Schmedt A, Gotte M, Heinig J, Kiesel L, Klockenbusch W, Steinhard J. Evaluation of placental syndecan-1 expression in early pregnancy as a predictive fetal factor for pregnancy outcome. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(2):131–7.

Croy BA, Yamada AT, DeMayo FJ, Adamson SL. The guide to investigation of mouse pregnancy. 1st ed: Academic Press; 2014.

Paria BC, Das SK, Andrews GK, Dey SK. Expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene is regulated in mouse blastocysts during delayed implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(1):55–9.

Psychoyos A. Uterine receptivity for nidation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;476:36–42.

Long JA, Evans HM. The oestrous cycle in the rat and its associated phenomena. Oakland: University of California Press; 1922.

Allen E. The oestrous cycle in the mouse. Am J Anat. 1922;30(3):297–371.

Marcondes FK, Bianchi FJ, Tanno AP. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz J Biol. 2002;62(4A):609–14.

Redina OE, Amstislavsky S, Maksimovsky LF. Induction of superovulation in DD mice at different stages of the oestrous cycle. J Reprod Fert. 1994;102(2):263–7.

Stepp MA, Gibson HE, Gala PH, Iglesia DD, Pajoohesh-Ganji A, Pal-Ghosh S, et al. Defects in keratinocyte activation during wound healing in the syndecan-1-deficient mouse. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 23):4517–31.

Bonaparte D, Cinelli P, Douni E, Herault Y, Maas M, Pakarinen P, et al. FELASA guidelines for the refinement of methods for genotyping genetically-modified rodents: a report of the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations Working Group. Lab Anim. 2013;47(3):134–45.

McLean AC, Valenzuela N, Fai S, Bennett SA. Performing vaginal lavage, crystal violet staining, and vaginal cytological evaluation for mouse estrous cycle staging identification. J Vis Exp : JoVE. 2012;67:e4389.

Fischer AH, Jacobson KA, Rose J, Zeller R. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. CSH Protoc. 2008;2008:pdb prot4986.

Huang X, Fu Y, Charbeneau RA, Saunders TL, Taylor DK, Hankenson KD, et al. Pleiotropic phenotype of a genomic knock-in of an RGS-insensitive G184S Gnai2 allele. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(18):6870–9.

Michael B, Yano B, Sellers RS, Perry R, Morton D, Roome N, et al. Evaluation of organ weights for rodent and non-rodent toxicity studies: a review of regulatory guidelines and a survey of current practices. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(5):742–50.

Nirogi R, Goyal VK, Jana S, Pandey SK, Gothi A. What suits best for organ weight analysis: review of relationship between organ weight and body/brain weight for rodent toxicity studies. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5(4):1525–32.

Schenkel J. Transgene Tiere. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2007. ISBN-13 9783540282686.

Graham S, Gandelman R. The expression of ano-genital distance data in the mouse. Physiol Behav. 1986;36(1):103–4.

Wennemuth G, Carlson AE, Harper AJ, Babcock DF. Bicarbonate actions on flagellar and Ca2+ −channel responses: initial events in sperm activation. Development. 2003;130(7):1317–26.

Bruner-Tran KL, Ding T, Yeoman KB, Archibong A, Arosh JA, Osteen KG. Developmental exposure of mice to dioxin promotes transgenerational testicular inflammation and an increased risk of preterm birth in unexposed mating partners. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105084.

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, Team RC. nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R software 2016; R package version 3.1–128.

The Jackson Laboratory. https://www.jax.org/jax-mice-and-services/strain-data-sheet-pages/body-weight-chart-000664. Accessed 15 Nov 2017.

Caligioni CS. Assessing reproductive status/stages in mice. Current protocols in neuroscience / editorial board, Jacqueline N Crawley [et al]. 2009;Appendix 4:Appendix 4I.

Barkley MS, Bradford GE. Estrous cycle dynamics in different strains of mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1981;167(1):70–7.

Parkes A. The length of the oestrous cycle in the unmated normal mouse: records of one thousand cycles. J Exp Biol. 1928;5(4):371–7.

Mouse Genome Informatics http://www.informatics.jax.org/. Accessed 20 Oct 2017.

Paria BC, Elenius K, Klagsbrun M, Dey SK. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor interacts with mouse blastocysts independently of ErbB1: a possible role for heparan sulfate proteoglycans and ErbB4 in blastocyst implantation. Development. 1999;126(9):1997–2005.

Mouse Genome Informatics. http://www.informatics.jax.org/external/festing/mouse/docs/C57BL.shtml. Accessed 15 Nov 2017.

Weber EM, Algers B, Wurbel H, Hultgren J, Olsson IA. Influence of strain and parity on the risk of litter loss in laboratory mice. Reprod Domest Anim. 2013;48(2):292–6.

König B, Markl H. Maternal care in house mice. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1987;20(1):1–9.

Kasza I, Suh Y, Wollny D, Clark RJ, Roopra A, Colman RJ, et al. Syndecan-1 is required to maintain intradermal fat and prevent cold stress. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(8):e1004514.

Silverman WA, Fertig JW, Berger AP. The influence of the thermal environment upon the survival of newly born premature infants. Pediatrics. 1958;22(5):876–86.

Paigen B, Svenson KL, Von Smith R, Marion MA, Stearns T, Peters LL, et al. Physiological effects of housing density on C57BL/6J mice over a 9-month period. J Anim Sci. 2012;90(13):5182–92.

Vainio S, Lehtonen E, Jalkanen M, Bernfield M, Saxen L. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions regulate the stage-specific expression of a cell surface proteoglycan, syndecan, in the developing kidney. Dev Biol. 1989;134(2):382–91.

Ledin J, Staatz W, Li JP, Gotte M, Selleck S, Kjellen L, et al. Heparan sulfate structure in mice with genetically modified heparan sulfate production. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(41):42732–41.

Bullock SL, Fletcher JM, Beddington RS, Wilson VA. Renal agenesis in mice homozygous for a gene trap mutation in the gene encoding heparan sulfate 2-sulfotransferase. Genes Dev. 1998;12(12):1894–906.

Celie JW, Katta KK, Adepu S, Melenhorst WB, Reijmers RM, Slot EM, et al. Tubular epithelial syndecan-1 maintains renal function in murine ischemia/reperfusion and human transplantation. Kidney Int. 2012;81(7):651–61.

Chubb C. Genes regulating testis size. Biol Reprod. 1992;47(1):29–36.

Brucato S, Bocquet J, Villers C. Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans: target and partners of the basic fibroblast growth factor in rat Sertoli cells. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269(2):502–11.

Levallet G, Bonnamy PJ, Levallet J. Alteration of cell membrane proteoglycans impairs FSH receptor/Gs coupling and ERK activation through PP2A-dependent mechanisms in immature rat Sertoli cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(6):3466–75.

Chubb C. Genetically defined mouse models of male infertility. J Androl. 1989;10(2):77–88.

Macleod DJ, Sharpe RM, Welsh M, Fisken M, Scott HM, Hutchison GR, et al. Androgen action in the masculinization programming window and development of male reproductive organs. Int J Androl. 2010;33(2):279–87.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Coordination Center for Clinical Trials of the University hospital Düsseldorf (A. Rottmann) for the calculation of the nonlinear mixed-effects models and the department of applied statistics of the Heinrich-Heine-University of Düsseldorf for the linear mixed-effects models (K. Fischer and T. Tietz) as well as Prof. Ruth Grümmer, Prof. Alexandra Gellhaus (University Hospital Essen), Sonja Green (Heinrich-Heine-University of Düsseldorf), Dr. Olga Altergot-Ahmad and Dr. Jana Liebenthron (University Hospital Düsseldorf) for technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) to AP Bielfeld (HE 3544/2–2 and 2–3).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CG carried out most of the experiments, data analysis and manuscript preparation and was involved in study design. APB conceived and designed the study and was involved in data analysis and manuscript preparation. SJP helped with the ELISA for the quantification of SDC1. JSK helped with editing of the paper and statistical analysis. MG provided us with some breeding pairs of Sdc1−/− mice and shared his expertise in the field of Syndecan-1. WPMB helped with animal weighing, organ isolation and organ weighing and was involved in data analysis, and manuscript preparation. DMBB conceived and designed the study, helped with animal weighing, organ isolation and organ weighing and was involved in data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Planning and conduction of the experimental procedures as well as maintenance of the animals was carried out in accordance to the German Legislation for the Care and Use of Laboratory animals and the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments. Experiments were approved by the State Office for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection (LANUV, State of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) (87–51.04.2010.A061, 84–02.04.2011.A317).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest regarding the publication of this paper or financial interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gougoula, C., Bielfeld, A.P., Pour, S.J. et al. Physiological and anatomical aspects of the reproduction of mice with reduced Syndecan-1 expression. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 17, 28 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-019-0470-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-019-0470-2