Abstract

Background

Age increases the risk of emergency department [ED] visits. Health related quality of life (HRQoL) is often estimated as an outcome of ED visits, but it can be a risk factor of ED visits. This study aims to assess the association of HRQoL with time to first ED visit and/or frequent ED use in older adults during four-year period and if this association differs in 66–80 and 80+ age groups.

Methods

Data from the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care-Blekinge of wave 2007–2009 was used in combination with electronic health records on ED visits. The analytical sample included 673 participants of age 66 years and older with information on HRQoL. Cox proportional hazard model was used to assess the association between HRQoL and time to first ED visit. Logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the association of HRQoL with frequent ED use.

Results

During the study period, 55.3% of older adults visited the ED and 28.8% had a frequent ED use. Poor physical HRQoL was independently associated with first ED visit both in total sample (p < 0.001) and in 66–80 (p < 0.001) and 80+ (p = 0.038) age groups. Poor mental HRQoL had no significant association with first ED visit and frequent ED use.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that poor physical HRQoL is associated with time to first ED visit in older adults. Therefore, physical HRQoL should be considered while planning interventions on the reduction of ED utilisation in older adults. Explanatory factors of frequent ED use may differ in age groups. Further studies are needed to identify associated factors of frequent ED visits in 80+ group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aging is a process that increases risk of functional decline and multiple health problems. In old age, fluctuations in health status from one day to another can lead to acute needs of health care. The emergency department (ED) is often an inappropriate setting for the older people with complex health problems, because of its stressful environment, long length of stay, and poor continuity of care. In Sweden, people of age 65 or more make up approximately 35% of all ED visits [1]. Frequent ED use contributes to overcrowding and longer length of stay at ED [2]. According to the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare [3], age is an important factor for longer length of stay at ED. This points towards the importance of determining age-specific contributing factors of ED visits in order to prevent avoidable acute visits. Subjective perceptions of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) can be a predictive of acute health care utilisation.

Quality of Life (QoL) is a dynamic and multidimensional concept referring to the general wellbeing of individuals. Previous research has demonstrated that health is a dominant domain of QoL according to the older people’s own definitions [4, 5], can be operationalised as the subjective perception of physical and mental health estimated from self-perceived mobility, pain, energy level, sadness, and social participation [4, 6]. A recent study on Swedish older people (65–84 years) has shown that there are stable trends in reporting poor self-rated health and severe problems in different domains of HRQoL over 8 years [7]. In clinical research, HRQoL is often measured as an outcome of a disease, intervention [8] or health care visit [9]. Poradzisz and Florczak, [8] argue that HRQoL could influence adherence to medication, healthy life style and self-management. Therefore, instead of seeing HRQoL only as a designated outcome, future research should consider HRQoL as an input. This study will focus on whether HRQoL is associated with time to first ED visit and/or frequent ED use.

Previous studies have shown that self-rated health and HRQoL are important predictors of ED visit [10,11,12] and frequent ED use [2]. However, these studies have focused on people with specific health problems, have sampled from a broad age range [10, 11], or have included outpatients of geriatric centre or people from particular settings, such as older people living in their own homes [12]. Focusing on specific settings or health problems may only help to reduce ED visits for particular group and using samples that have a broad age range may mask the influence of age specific characteristics such as living circumstances, high risk of multi-morbidity or poor HRQoL [7]. Therefore, to reduce ED visits it is essential to determine age specific risk factors of ED and consider frequent utilization of ED [2]. However, there is a lack of studies on HRQoL and ED visits based on populations including both people living in their own homes and in institutions of older adults and analysing separate age groups. Moreover, previous research has shown that sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, education, housing, health care use [13], health and functional status [12, 13] and living alone [14] can explain ED visits in older people. Therefore, it is important to consider these explanatory variables while exploring the association between HRQoL and ED visits.

The aim of this study was to investigate if HRQoL is associated with time to first ED visit and/or frequent ED use in older adults during a 4 year-period. A second aim was to examine whether this association differs between the 66–80 and 80+ age groups.

Methods

Study design, population and procedure

This study has a prospective cohort design. It is based on the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care (SNAC), which is an ongoing longitudinal multicentre cohort study on adults of age 60 years and more, with its first data collection wave in 2001–2003. Data was collected via self-administrated questionnaires. In SNAC, participants are followed up every sixth years for < 80 and every third year for 80+. The following age cohorts are included 60, 66, 72, 78, 81, 84, 87, 90, 93, and 96 years. For further details of SNAC, see [15].

In this study, data from one out of four sites of SNAC, that is, SNAC-B (Blekinge), is used. SNAC-B covers a community of Sweden with approximately 62,300 inhabitants. In SNAC-B, national population register was used to invite the subjects for participation in study. For age cohorts 60, 66, 72 and 78, people were selected randomly, while the entire population was invited to participate in the study for age cohorts 81, 84, 87, 90, 93 and 96 years. In the SNAC-B of wave 2007–2009, 978 subjects of age ≥ 66 years were invited to participate in the study. The subjects of age cohort 60 years were not included in this wave as it was the first follow up after 6 years of those who participated in the wave 2001–2003 of SNAC-B. Of 978 invited participants, 841 (85.9%) agreed to participate in the study, 63 refused to participate, 46 received the invitation but died before data collection, and other reasons of non-participation were poor health (n = 12), moved to another region of Sweden (n = 10) or not being reachable (n = 6).

In the present study, data from the SNAC-B of wave 2007–2009 was used as baseline. The inclusion criteria used in this study were that the participants should be 66 years of older and have provided information on HRQoL, which gave an analytical sample of 673 participants of age ≥ 66 years including individuals living in their own homes and institutionalised housing. Electronic health care record was used to obtain information on ED visits during 4 years from baseline. No difference was observed for ED visits for who did or did not provide information on HRQoL. However, individuals with missing information on HRQoL were older, more dependent in their activities of daily living (ADL) and their instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and they more likely to live in institutions, live alone and have diseases/illnesses.

Data was collected in accordance to the Helsinki declaration, and both verbal and written informed consent was obtained. The SNAC-B in combination with electronic health record has been awarded ethical approval by the ethics committee of Lund University (LU 128–00, LU 604–00).

Materials

In this study, time to first ED visit and frequent ED use served as dependent variables in the analyses. Information on ED visits was obtained from electronic health record held by the Blekinge County Hospital of Sweden, and was dichotomised as having/not having at least one ED visit during 4 years. In previous research, a varying number of visits (≥4 - ≥6) over different time periods have been used to define frequent ED use [2, 16, 17]. In this study, frequent ED use was defined as having four or more ED visits during a 4 year-period.

HRQoL was measured at baseline via Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12), collected through the questionnaire. SF-12 is a validated instrument [6] and is widely used in older adults. It consists of two dimensions: physical and mental. Physical HRQoL includes subjective perception of general health, difficulty in performing moderate activities, climbing of several flights of stairs, bodily pain, and accomplishing less due to physical health, while mental HRQOL includes not being careful in daily activities, accomplishing less due to mental health, social interaction, energy level, sadness, calmness, and peacefulness [6]. Sullivan’s algorithm was used to compute the SF-12 score [18]. The score of each dimension of SF-12 ranges from 0 (poor) to 100 (good) HRQoL. There is no gold standard definition of poor HRQoL. Lowest quartile of HRQoL score was used to define the poor HRQoL [19].

Information on other independent variables was collected through the questionnaire. Dichotomous variables were used for gender (male/female), housing (living in their own home/institutionalised housing), living arrangement (living alone/together with somebody), and education (primary school education/higher education). A continuous variable was constructed for number of diseases/illnesses (cardiovascular, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, depression, dementia, fracture, osteoporosis, thyroid, tuberculosis, Parkinson’s disease, asthma, trauma, inflammation, epilepsy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bipolar, cataract, sleep apnea, and snoring). Score “1” was given for each disease, ranging from 0 (no disease) to score 20. Katz index was used to measure the activities of daily living (ADL; bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence and feeding) [20], and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL; cleaning, transportation, shopping and cooking) [21]. The score “1” was given for each dependency with score range 0–6 for ADL and 0–4 for IADL. Functional dependence was defined as ADL ≥1 and IADL ≥1, respectively.

Statistical analysis

As broad age ranges may mask the influence of changes in the demographic characteristics and health status of study population with age, the study sample was stratified into two age groups: 66–80 years and 80+ years. To make comparison between age groups Chi-squared test was used for binary data and t-test for interval data. Due to the significant differences in the characteristics of two age groups (see Table 1) further analysis were conducted both for the whole group and separately for each age group. To estimate the association of HRQoL with ED visits, dichotomous variables were constructed for physical and mental HRQoL. The score in the lowest quartile was defined as poor HRQoL. The cut-offs ≤33.2 and ≤ 50.1were used to define poor physical and mental HRQoL, respectively. Time to event data was computed from the date of baseline data collection to the date of first ED visit during 4 year-period. Time from baseline to mortality and/or end of follow-up (31 December 2011) was used as censored.

Cox-proportional hazard model [22] was used to test the association of physical and mental HRQoL with time to first ED visit. To avoid association by chance, physical and mental HRQoL variables were entered with all independent variables simultaneously at the first step of Cox proportional model and backward Likelihood Ratio (LR) method was used. The LR accounts for likelihood of a variable to satisfactorily explain outcome variable [23]. Default setting of probability for stepwise entry, that is, 0.05 entry and 0.10 for removal was used. The results are presented as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Logistic regression was used to test the association of physical and mental HRQoL with frequent ≥4 ED visits. In the logistic regression models, all variables were entered simultaneously and backward LR method was used. The results are presented as odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI.

In order to analyse the stability (internal validation) of final models in the Cox and Logistic regression bootstrap approach with 1000 bootstrap samples (default settings) was performed [24]. In the bootstrap, simple sampling method with bias-corrected and accelerated confidence interval type were used. To test significance, p < 0.05 was used. SPSS version 24 for Windows was used to conduct the analysis.

Results

Descriptive analyses

At baseline, the mean age of the participants was 76.8 years and 43.4% of them were men. The mean scores of physical and mental HRQoL were significantly lower in the 80+ age group compared to the 66–80 age group, and the percentages of participants with poor physical and mental HRQoL were higher in the 80+ group than 66–80 group (p < .001) (Table 1). In addition, compared to the 66–80 age group, individuals in the 80+ group were more likely to live in institutionalised housing (p < 0.001), live alone (p < 0.001), have primary school education (p = 0.001), and be dependent in ADL and IADL (p < .001). However, the mean number of diseases/illnesses was higher in the 66–80 group than 80+ group (p = .048). During the 4 year-period, 55.3% of the total sample had at least one ED visit and 28.8% had frequent ED visits. The percentage of individuals having an ED visit was higher in the 80+ group than 66–80 years group (p < .001). No significant difference between the age groups were observed regarding frequent ED use.

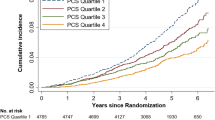

The median follow-up period was 2.77 years (range 0.01 to 4.42 years). Compared to the 66–80 age group, people aged 80+ were more likely to have one or more ED visits during the study period (Fig. 1).

Multivariate analyses of time to first ED visit

Poor physical HRQoL showed 68% (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.29–2.20) increased hazard of time to first ED visit compared to good physical HRQoL, in the total study population (Table 2, final model). Association between poor physical HRQoL and time to first ED was also significant in 66–80 (HR 1.97, 95% CI 1.34–2.88) and 80+ (HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.02–2.10) age group. However, no significant association between poor mental HRQoL and time to first ED visit was observed.

Moreover, age above 80 was significantly associated with time to first ED visit (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.34–2.25) in the total study sample. For the 66–80 age group, people with diseases/illnesses (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02–1.29) exhibited increased likelihoods of time to first ED visit, but not in the 80+ age group.

Multivariate analyses of frequent ED use

In the total study population, poor mental HRQoL was significantly associated (OR 1.88, 95% CI 1.07–3.32) with frequent ED use compared to good mental HRQoL (Table 3, final model). However, this association no longer remained significant after the robustness analysis done by bootstrap approach. For frequent ED use, physical HRQoL was not significant. In the 66–80 age group, people living in institutionalised housing (OR 11.69, 95% CI 1.04–131.62), having primary education only (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.10–4.88), and being dependent in ADL (OR 3.68, 95% CI 1.01–13.29) were more likely to have frequent ED use.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine whether HRQoL is associated with time to first ED visit and/or frequent ED use in older people and if this association differs between the 66–80 and 80+ age groups. Fifty five percent of the total sample had at least one ED visit during 4 year-period and twenty eight percent had frequent ED use. Poor physical HRQoL was significantly associated with the time to first ED visit both in the total sample and in both age groups. For frequent ED use, associations with poor physical and mental HRQoL were not significant. Other significant factors of time to first ED visit were age above 80 in total sample and number of diseases/illnesses in 66–80 age group. Institutionalised housing, primary education, and ADL dependence were significantly associated with frequent ED use in 66–80 age group, however not in 80+ group.

Age may not have a direct correlation with time to first ED visit, but the risk of health problems associated with aging increase the risk of an ED visit. In this study, the characteristics of the 80+ age group can explain the association between the 80+ age category and time to first ED visit. Risk factors such as poor perceived health and aging may have some similarities with number of diseases, ADL and IADL dependence [25]. In our study, this may have masked the effect of other variables, such as IADL. Therefore, different models were tried by excluding HRQoL, ADL and IADL (not shown here). Exclusion of HRQoL improved the effect of IADL and number of diseases/illnesses while exclusion of ADL and IADL did not effect on the significance of HRQoL.

The association between poor physical HRQoL and time to first ED visit both in the total sample and age groups are in line with the findings of previous research [10, 12]. A mixed method study [4] showed that physical health was the most important domain of QoL for older people and that this might be due to the fact that poor physical health impacts on mobility, which ultimately leads to dependence. The measurement of physical HRQoL is broader and includes not only subjective assessments of health but also the impact of subjective health on individual’s mobility and independence. This may explain the association between physical HRQoL and time to first ED visit in present study. Findings suggest that improvement in physical HRQoL can contribute to decrease the ED utilization in older people. Previous research suggests that preservation of mobility and/or functional ability and health promotion counselling can positively contribute to self-perceived health [9, 25].

In the present study, perhaps surprisingly the number of diseases/illnesses showed increased likelihood for ED visits in 66–80 but not in the 80+ group. This can be explained by the characteristics of the study sample, that is, that the 80+ group had a lower mean number of diseases/illnesses than the 66–80 group and by “selective mortality”. Participants with more health problems may have not reached to the age of 80+ or did not participate in the study because of their health status [15].

Poor mental HRQoL was not significant for the time to first ED visit and/or for frequent ED use. Lack of studies on the association of mental HRQoL and ED visits limit the comparison and explanation of this finding in relation to previous research. However, this finding contradicts a Norwegian study on hospital admissions in nursing home residents [26]. One explanation could be the different outcomes, that is, that hospital admissions that can be either planned or unplanned while ED visits are always unplanned. Another explanation to the contradictory results could be that the study population in the Norwegian study was limited to nursing home residents [26].

Institutionalised housing, primary school education and dependence in ADL were significant risk factors of frequent ED use in 66–80 age group. However, variables included in this study did not explain frequent ED use in 80+ group. Age is often considered as a control variable in the studies on ED visits [2, 12]. This limits the ability to compare with previous research and find explanations to why some variables were important for below 80 age group but not in 80+. Thus, future studies are warranted to explore the risk factors of frequent ED use in 80+ group.

Strengths and limitations of the study

There are few potential limitations that should be considered while interpreting findings of this study. HRQoL is a subjective health measure that is dynamic in nature, but it is only measured at one time point in this study. Moreover, aging is not a state but a process associated with health problems, and the severity of these health conditions can vary over time, particularly in the 80+ age group. This might have influenced the findings of this study. A limitation of this study is that self-reported information on independent variables such as diseases/illnesses might be influenced by recall bias. Moreover, this study was based on a regional sample of older adults and, considering organisational differences across regions (and countries), results may not be generalised to the whole population. In addition, participants who provided information on HRQoL were younger, healthier with fewer diseases/illnesses (mean ≈ 1.4), better functional ability, and more likely to live in their own home together with relatives than those who did not respond to the HRQoL item. However, no difference was observed for ED visits between those who did or did not provide information on HRQoL. In this study, population with cognitive impairment was underrepresented. Current and previous health care use could explain current ED use [13], but this was not considered in this study due to unavailability of information.

A strength of this study is that it is based on a population based sample rather than a clinical sample, and that it includes older adults living in their own home and in institutionalised housing. Another strength is that information on ED visits was obtained from hospital records, that is, recall bias did not influence the outcome variables of this study. A prospective study design with a long follow-up period and separate analyses for different age groups are other strengths of this study.

Conclusion

In this study, 55.3% of older adults visited the ED and 28.8% had a frequent ED use during 4 year-period. This study identified different explanatory variables of ED visits specific to each age group. This highlights the importance of age stratified analyses. However, some similarities were also observed, for example poor physical HRQoL increased the likelihood of first ED visit in both age groups.

Poor physical HRQoL was associated with increased hazard of time to first ED visit independent of diseases/illnesses, both in total sample and in age groups. Findings suggest that improvement of physical HRQoL in adults of age ≥ 66 years has the potential to reduce the first ED visit. Health promotion counselling in other settings than EDs, such as geriatric centres or primary health care, could help to identify and address risk factors behind poor HRQoL. Ultimately, this could contribute in the decline of acute care utilization. Risk factors of frequent ED use in 80+ group are still unclear, and future studies on this age group is needed.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activity of Daily Living

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- ED:

-

Emergency Department

- HR:

-

Hazards Ratio

- HRQoL:

-

Health Related Quality of Life

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activity of Daily Living

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SF:

-

Short Form

- SNAC-B:

-

The Swedish National Study on Aging and Care-Blekinge

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Science

References

Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU). Omhändertagande av äldre som inkommer akut till sjukhus – med fokus på sköra äldre. En systematisk litteraturöversikt [Care of the older people that comes in emergency at hospital: a focus on frail older people. A systematic literature overview.] 2013. https://www.sbu.se/contentassets/5f0e7213e73b4369acd4874fd3dcbf89/akutvard_aldre.pdf. Accessed 22 March 2017.

Hunt KA, Weber EJ, Showstack JA, Colby DC, Callaham ML. Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(1):1–8.

National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden. Väntetider och patientflöden på akutmottagningar [Waiting time and patient’s flood at emergency] Rapport februari 2017. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/20493/2017-2-16.pdf Accessed 22 Mar 2017.

Milte CM, Walker R, Luszcz MA, Lancsar E, Kaambwa B, Ratcliffe J. How important is health status in defining quality of life for older people? An exploratory study of the views of older south Australians. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12(1):73–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-013-0068-3.

Walker A. Ageing and quality of life in Europe. In: Dannefer D, Phillipson C, editors. The SAGE handbook of social gerontology. London: SAGE; 2010. p. 573–86.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Modig K, Virtanen S, Ahlbom A, Agahi N. Stable or improved health status in the population 65 years and older in Stockholm, Sweden-an 8-year follow-up of self-reported health items. Scand J Public Health. 2016;44:480–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816636248.

Poradzisz M, Florczak KL. Quality of life: input or outcome? Nurs Sci Q. 2013;26(2):116–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318413477149.

Andersson LB, Marcusson J, Wressle E. Health-related quality of life and activities of daily living in 85-years-olds in Sweden. Health Soc Care Commun. 2014;22(4):368–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12088.

Chamberlin AM, Manemann SM, Dunlay SM, Spertus JA, Moser DK, Berardi C, et al. Self-rated health predicts health care utilization in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014; 3(3). doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.114.000931.

Blanco-Aparicio M, Vazquez I, Pita-Fernandez S, Pertega-Diaz S, Verea-Hornando H. Utility of brief questionnaires of health-related quality of life (Airways Questionnaire 20 and Clinical COPD Questionnaire) to predict exacerbations in patients with asthma and COPD. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013; 11(85). doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-85.

Fan L, Shah MN, Veazie PJ, Friedman B. Factors associated with emergency department use among the rural elderly. J Rural Health. 2011;27(1):39–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00313.x.

Krieg C, Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Dufour I. Individual predictors of frequent emergency department use: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:594. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1852-1.

Hastings SN, George LK, Fillenbaum GG, Park RS, Burchett BM, Schmader KE. Do lack of social support lead to more ED visits for older adults? Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(4):454–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2007.07.005.

Lagergren M, Fratiglioni L, Hallberg IR, Berglund J, Elmståhl S, Hagberg B, Holst G, Rennemark M, Sjölund BM, Thorslund M, Wiberg I, Winblad B, Wimo A. A longitudinal study integrating population care and social services data. The Swedish National Study on aging and care (SNAC). Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16(2):158–68.

Wajnberg A, Hwang U, Torres L, Yang S. Characteristics of frequent geriatric users of an urban emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(2):376–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.056.

Milbrett P, Halm M. Characteristics and predictors of frequent utilization of emergency services. J Emerg Nurs. 2009;35(3):191–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2008.04.032.

Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Taft C. SF-36 Health questionnaire. Swedish Manual and interpretation guide [In Swedish]. 2 ed. Gothenburg: Health Care Research Unit, Medical Faculty, Gothenburg University; 2002.

Naseer M, Fagerström C. Prevalence and association of undernutrition with quality of life among Swedish people aged 60 years and above: results of SNAC-B study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19(10):970–9.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged, the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9.

Åsberg KH, Sonn U. The cumulative structure of personal and instrumental ADL: a study of elderly people in a health district. Scand J Rehab Med. 1989;21(4):171–7.

Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Royal Stat Soc. 1972;34(2):187–220.

Machin D, Cheung YB, Parmar M. Survival analysis: a practical approach. England, UK: Wiley; 2006.

Altman DG, Andersen PK. Bootstrap investigation of the stability of a cox regression model. Stat Med. 1989;8:771–83.

Bryant LL, Beck A, Fairclough DL. Factors that contribute to positive perceived health in older population. J Aging Health. 2000;12(2):169–92.

Drageset J, Eide GE, Ranhoff AH. Better health-related quality of life (mental component summary), having a higher level of education, and being less than 75 years of age are predictors of hospital admission among cognitively intact nursing home residents: a 5-year follow-up study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:275–82.

Acknowledgements

The Swedish National Study on Aging and Care, SNAC (www.snac.org), was financially supported by the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Sweden, and the participating county councils, municipalities and university departments. The study was also supported by Dalarna County Council, Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, Dalarna University, and Blekinge Center of Competence, Blekinge County Council. This study was accomplished within the context of the Swedish National Graduate School for Competitive Science on Ageing and Health (SWEAH) funded by the Swedish Research Council.

Funding

The study was supported by Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (grant no. 2015–00440),

Availability of data and materials

The dataset are not publicly available as it is obtained from another project, The Swedish National Study on Aging and Care. Data can be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request with permission of third party.

Author’s contributions

All authors contributed in the development of study design, interpretation of analysis, drafting and finalising the manuscript. CF computed scores of SF-12 instrument. MN conducted data analysis. MN, LD and CF contributed in the interpretation of results. MN drafted manuscript and LD and CF checked the manuscript. LD also contributed in the language check. MN finalised the manuscript with inputs from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is conducted in accordance to the Helsinki declaration. Both verbal and written informed consent was obtained. The SNAC-B in combination with electronic health care record has been awarded ethical approval by the ethics committee of Lund University (LU 128–00, LU 604–00).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing of interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Naseer, M., Dahlberg, L. & Fagerström, C. Health related quality of life and emergency department visits in adults of age ≥ 66 years: a prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 16, 144 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0967-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0967-y