Abstract

Background

Since several malaria parasite species are usually present in a particular area, co-infections with more than one species of Plasmodium are more likely to occur in humans infected in these areas. In many mixed infections, parasite densities of the cryptic species may be low and often not recognized in clinical practice.

Case presentation

Two children (3 and 6 years old) adopted recently from Central African Republic were admitted to hospital because of intermittent fever. Thin blood smears stained with Giemsa showed Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium malariae co-infection for both children at admission. They were both treated with atovaquone-proguanil combination for 3 days. At day 7, both thin blood smears examination remained negative but at day 28, thin blood smear was positive for P. malariae trophozoites and for Plasmodium ovale for the girl and her brother, respectively. Samples collected at day 1 and day 28 were submitted to real-time PCR showing the presence of the three parasite species (P. falciparum, P malariae and P. ovale) in admission blood samples from the two children and only P. ovale at day 28.

Conclusions

Twenty-eight days follow-up after treatment led to detection of a third parasite species in the blood of these two patients suggesting covert co-infection and a delayed appearance of one cryptic species following treatment. Concurrently infecting malaria species could be mutually suppressive, with P. falciparum tending to dominate other species. These observations provide more evidence that recommendations for treatment of imported malaria should take into account the risk of concurrent or cryptic infection with Plasmodium species. Clinicians and biologists should be aware of the underestimated frequency of mixed infections with cryptic species and of the importance of patient follow-up at day 28. Future guidelines should shed more light on the treatment of mixed infection and on the interest of using artemisinin-based combinations for falciparum and non-falciparum species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mixed-species malaria infections have received sporadic attention [1], and the trend toward malaria control in some endemic areas should reduce the occurrence of concurrent infection with more than one species of Plasmodium. However, diagnostic of these mixed-infections is rare in clinical practice, and probably underestimated by microscopy. Expert microscopists are uncommon in clinical laboratory, and distinguishing the species from young trophozoite forms of Plasmodium parasites is sometimes difficult [2]. The life-threatening P. falciparum is obviously taking most of the attention considering the potential consequences of a wrong diagnosis, and other species are sometimes scanned with less intensity. In case of mixed infection, the concurrent species is mostly below the threshold of microscopy. For example, the ratio of Plasmodium malariae/P. falciparum was described as extremely low in a study conducted in Ivory Coast and the protective effect of lengthy subclinical P. malariae infections was suspected [3]. Moreover, the liver stage of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale, which are responsible for relapses, are not detectable [1]. The delayed appearance of a cryptic species after successful treatment of the first diagnosed species has been reported in area endemic for P. falciparum and P. vivax malaria [4].

It has been known from decades that antagonism between species may lead to a rapid decrease of circulating parasites, such as P. malariae when inoculated with P. vivax in an attempt to treat neurosyphilis [5].

Triple species infection are known, but remain rare in the literature. Two parallel cases of triple infections (P. falciparum and P. malariae, followed by P. ovale delayed infection) in two adopted children from Central African Republic are presented here to document the risk of late reappearance and the need for clinical and parasitological follow-up. These cases focused more light on the risk of treating each malaria species by drugs with different efficacy.

Case report

Two children (3 and 6 years old) were admitted to hospital because of intermittent fever and suspected malaria. They have been adopted recently and came back from Central African Republic a week previously.

The 6-year-old boy presented with a temperature of 37.9 °C, a systolic murmur in mitral focus, and a hepatosplenomegaly. The haemoglobin level was 6.7 g/dL, the mean corpuscular volume was 65 fL, and the platelet count was 216 G/L. Biochemical tests showed a normal liver function, increased serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (291 U/L, reference range 135–250 U/L) and C-reactive protein (73, reference value <5). A coagulation test result for the prothrombin time–international normalized ratio was slightly prolonged (14.7 s with a ratio at 67%, reference range 12.5 s with a ratio at 75–100%). An ultrasonographic abdominal examination showed hepatomegaly (107 mm thickness along the mammary line, reference value for this age 90 mm), and splenomegaly (115 mm, reference range 70–96 mm), and lack of deep lymph nodes. An ultrasonographic heart examination reported no abnormalities.

The 3-year-old girl, presented with a temperature of 37 °C, bilateral crackles predominant right, and a hepatosplenomegaly. The haemoglobin level was 6.3 g/dL, the mean corpuscular volume was 71.6 fL, and the platelet count was 138 g/L. Biochemical tests showed a normal liver function, increased serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (379 U/L) and C-reactive protein (48 mg/mL). A coagulation test result for the prothrombin time–international normalized ratio was slightly normal. Ultrasonographic abdominal examination reported a splenomegaly (100 mm, and lack of deep lymph nodes.

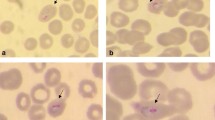

Thin blood smears stained with Giemsa showed P. falciparum and P. malariae co-infection for both children (P. falciparum 1.3% + P. malariae 0.14% and P. falciparum 0.03% + P. malariae 0.15% for girl and boy, respectively). A rapid diagnostic test (Palutop4 +, AllDiag, Strasbourg, France) showed three positive bands for the control, Plasmodium spp. (pLDH), and P. falciparum (pHRPII) markers.

Both children received 1 adult co-formulated tablet of Malarone, containing 250 mg atovaquone and 100 mg proguanil hydrochloride, per day for 3 days. The tablets were administered during the meal without addition of fat. The boy weighed 19 kg, the girl weighed 14.5 kg and the administered weight-based dose of atovaquone/proguanil was 10/5 and 17/7 mg/kg/day for the boy and girl respectively. They did not vomit and no other adverse events were noted during treatment. Both children received iron syrup supplementation and paracetamol.

Almost complete parasitaemia clearance was obtained at day 3 (P. falciparum <0.01% + P. malariae <0.01% and P. falciparum 0% + P. malariae 0.02%, for girl and boy respectively). These figures are not uncommon because atovaquone-proguanil is known to act relatively slowly. Apyrexia was obtained at day 2 and patients were discharged on day 5 and did not return until scheduled appointments for control of parasitaemia on day 7.

At day 7, both thin blood smears examination remained negative, while few picnotic parasites were detected on thick blood smears. Surprisingly, at day 28, thin blood smear from the girl was positive and revealed <0.01% P. malariae trophozoites while P. ovale (<0.01%) was detected from her brother’s blood. To confirm the species identification, the samples collected at day 1 and day 28 were submitted to real-time PCR as previously described [6]. Molecular diagnosis demonstrated the presence of the three parasite species (P. falciparum, P. malariae and P. ovale) in D0 samples from both children, and only P. ovale at day 28.

Both children were still apyretic and didn’t show any symptoms of infection. Considering the suspected parasitological failure of the atovaquone-proguanil treatment against P. ovale, patients were given a total dose of 25 mg/kg of chloroquine over 3 days. Both children were not glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient, but primaquine was not used to prevent relapses. Clinical and parasitological follow-up was performed and total parasite clearance was assessed by thin and thick blood smears at day 42, showing the absence of recurrence. Both children had non-haemolytic (normal haptoglobin), microcytic anaemia at admission to hospital and were found to have iron deficiency, which was successfully treated after 3 months of iron supplementation. Echocardiography examinations revealed that boy had an inorganic heart murmur. Gastrointestinal helminths were not found after 3 stool examinations for ova and parasites. Cysts of Entamoeba coli and Chilomastix mesnili were found in the boy’s stools, who was treated with secnidazole. Patients were then lost to follow-up.

Conclusion

Six different malaria species are known to infect humans: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale wallikeri, P. ovale curtisi and P. knowlesi [7]. Routine microscopical examination of thick and/or thin blood smears stained with Giemsa allows discrimination of four of these species, since P. ovale wallikeri is not distinguishable from P. ovale curtisi, and P. knowlesi is impossible to distinguish from P. malariae. Most of the rapid diagnostic tests available on the market showed lower performance for P. vivax (70.7% panel detection score) than for P. falciparum (85% panel detection score) in the round 6 of WHO [8]. Plasmodium ovale and P. malariae RDTs have not been evaluated so far. Molecular tests are the only methods allowing species identification with a good accuracy.

Mixed, or concurrent infections, are frequently reported in epidemiological studies conducted in endemic areas and probably underdiagnosed at an individual level. It is known that several Anopheles species, are able to carry more than one species, including the four main species for Anopheles gambiae [9]. There is no definitive evidence of a clinical or parasitological impact of mixed infections in humans. Plasmodium vivax is supposed to reduce the severity of P. falciparum infection; P. falciparum reduces the availability of red blood cells for P. vivax infection, and a theory of species-transcendenting density-dependant (STDD) regulation of multiple malaria infection has been proposed [10, 11].

There is no evidence that drugs used to treat the dominant specie may be ineffective against the cryptic species. Since ACTs are mainly recommended to treat falciparum malaria, and chloroquine to treat non-falciparum malaria, under-diagnosis of mixed infection may lead to inappropriate treatment of patients. In countries with chloroquine-resistant P. vivax, ACT is the treatment policy for non-falciparum infections. ACT is also recommended treatment of mixed infections [12]. In the two cases presented here, P. falciparum and P. malariae co-infection was successfully treated with atovaquone-proguanil, while asymptomatic P. ovale was detected at day 28. Unfortunately, it was not possible to know if the recurrence of P. ovale was due to drug resistance or relapse of liver stages, and cytochrome b gene mutation was not investigated due to low amount of samples. A plausible cause of this late therapeutic failure is the relatively insufficient dosage due to increased oral clearance of atovaquone in pediatric patients. However, failure to atovaquone-proguanil prophylaxis has been reported in travelers presenting P. ovale infection [13].

These observations provide more evidence that recommendations for treatment of imported malaria may take into account the risk of concurrent or cryptic infection with Plasmodium species presenting different sensitivity to drugs. Considering that information on drug resistance of non-falciparum species is scarce, clinician and biologists should take particular attention to patient follow-up at day 28.

Abbreviations

- fL:

-

fento-liter

- STDD:

-

species-transcendenting density-dependant

References

Mayxay M, Pukrittayakamee S, Newton PN, White NJ. Mixed-species malaria infections in humans. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:233–40.

Snounou G. Cross-species regulation of Plasmodium parasitaemia cross-examined. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:262–5 (discussion 266–267).

Black J, Hommel M, Snounou G, Pinder M. Mixed infections with Plasmodium falciparum and P. malariae and fever in malaria. Lancet. 1994;343:1095.

Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Chittamas S, Bunnag D, Harinasuta T. High rate of Plasmodium vivax relapse following treatment of falciparum malaria in Thailand. Lancet. 1987;2:1052–5.

Mayne B, Young M. Antogonism between species of malaria parasites in induced mixed infections. Public Health Rep. 1938;53:1289–91.

de Monbrison F, Angei C, Staal A, Kaiser K, Picot S. Simultaneous identification of the four human Plasmodium species and quantification of Plasmodium DNA load in human blood by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:387–90.

Sutherland CJ, Tanomsing N, Nolder D, Oguike M, Jennison C, Pukrittayakamee S, et al. Two nonrecombining sympatric forms of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium ovale occur globally. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1544–50.

WHO: Malaria rapid diagnostic test performance. Results of WHO product testing of malaria RDTs: round 6 (2014–2015). Geneva: World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204118/1/9789241510035_eng.pdf?ua=1.

Fontenille D, Lepers JP, Coluzzi M, Campbell GH, Rakotoarivony I, Coulanges P. Malaria transmission and vector biology on Sainte Marie Island. Madag J Med Entomol. 1992;29:197–202.

Bruce MC, Donnelly CA, Alpers MP, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW, Walliker D, et al. Cross-species interactions between malaria parasites in humans. Science. 2000;287:845–8.

Zimmerman PA, Mehlotra RK, Kasehagen LJ, Kazura JW. Why do we need to know more about mixed Plasmodium species infections in humans? Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:440–7.

WHO: Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241549127/en/.

Nolder D, Oguike MC, Maxwell-Scott H, Niyazi HA, Smith V, Chiodini PL, et al. An observational study of malaria in British travellers: Plasmodium ovale wallikeri and Plasmodium ovale curtisi differ significantly in the duration of latency. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002711.

Authors’ contributions

CB and GG were in charge of the cases. SP supervised the molecular analysis and was involved in literature search to draft the manuscript. All authors helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Guillaume Bonnot (CNRS UMR 5246, Lyon, France) for molecular tests.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Approval to use this case for educational purposes was obtained from the Rouen University Hospital.

Funding

Funds came from the Rouen University Hospital and the UMR 5246 CNRS Lyon, France.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bichara, C., Flahaut, P., Costa, D. et al. Cryptic Plasmodium ovale concurrent with mixed Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium malariae infection in two children from Central African Republic. Malar J 16, 339 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1979-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1979-5