Abstract

Background

Empathy allows a physician to understand the patient’s situation and feelings and respond appropriately. Consequently, empathy gives rise to better diagnostics and clinical outcomes. This systematic review investigates the level of empathy among medical students across the number of educational years and how this level relates to gender, specialty preferences, and nationality.

Method

In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), the authors conducted a systematic search of studies published between February 2010 and March 2019 investigating the level of empathy among medical students. The databases PubMed, EMBASE, and PsycINFO were searched. Studies employing quantitative methodologies and published in English or Scandinavian language and examining medical students exclusively were included.

Results

Thirty studies were included of which 24 had a cross-sectional and 6 a longitudinal study design. In 14 studies, significantly lower levels of empathy were reported by increase in the number of educational years. The remaining 16 studies identified both higher, mixed and unchanged levels. In 18 out of 27 studies it was reported that females had higher empathy scores than males. Only three out of nine studies found an association between empathy scores and specialty preferences. Nine out of 30 studies reported a propensity towards lower mean empathy scores in non-Western compared to Western countries.

Conclusion

The results revealed equivocal findings concerning how the empathy level among medical students develops among medical students across numbers of educational years and how empathy levels are associated with gender, specialty preferences, and nationality. Future research might benefit from focusing on how students’ empathy is displayed in clinical settings, e.g. in clinical encounters with patients, peers and other health professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Empathy is usually categorised as either affective (emotional), cognitive or a combination of both. The essence of affective empathy is compassion and the ability to enter into other peoples’ feelings (Einfühlung). Cognitive empathy is described as “the ability to understand someone’s situation without making it one’s own” [1]. In the clinical setting and within the context of the patient-physician relationship, it is predominantly the cognitive empathy type that is valued and strived for. Mercer and Reynolds [2] define clinical empathy as the ability to a) understand the patient’s situation, perspective and feelings (and their attached meanings); b) to communicate that understanding and check its accuracy and c) to act on that understanding with the patient in a helpful (therapeutic) way. An empathic physician is able to sense the patient’s feelings while at the same time sustaining his or her professionalism [3]. Empathy has been shown to contribute substantially to building and maintaining a good patient-physician relationship [4]. Studies on empathy among general practitioners (physicians specialised in general practice) concluded that a general practitioner’s display of empathy creates a relationship built on trust, openness, and safety and that a general practitioner’s empathic attitude makes the patient feel supported and listened to [5, 6]. Consequently, patients are more likely to disclose accurate and important information about themselves resulting in better diagnostics and clinical outcomes [7,8,9]. Steinhausen et al. [8] found that patients who rated their physician as having “high physician empathy” using the Consultation-and-Relational-Empathy (CARE) measure had a 20-fold higher probability of a better self-reported medical treatment outcome compared to patients who rated their physician to have “low physician empathy.” Furthermore, studying patients with diabetes, Hojat et al. [9] found a strong correlation between an empathic physician (measured through the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE)) and lower values of lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) and glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c). Beyond clinical outcomes, empathic communication has been shown to enhance patient satisfaction, compliance and patient empowerment [10,11,12]. Additionally, regarding physician-related benefits of empathy, physicians who perceive themselves as being empathic experience empathy as a source of professional satisfaction and meaningfulness protecting against burn-out [5, 13, 14]. As an offshoot of the large body of research documenting the beneficial effects of physician empathy, empathy development among medical students has become a comprehensive research topic. Moreover, the association between levels of empathy among medical students and variables such as gender, nationality and/or specialty preferences has received an increased focus among researchers. Hojat et al. [15] found that medical students interested in primary care specialties had higher empathy scores than students showing interests in technology and procedure orientated specialties. Female and male physicians are furthermore shown to approach the patient-physician relationship differently [16]. For example, female physicians value psychosocial factors more than male physicians and engage to a larger extent in patient-centred and/or relationship-centred communication [17]. These varying cultural, social and psychological influences on empathy levels are also reflected in the fact that findings from studies conducted in different countries vary to a high degree [18, 19]. Several research studies using student self-report measures to measure empathy levels have documented that a significant decline in empathy occurs among medical students as their training progresses [20, 21]. Contrary to these finding, however, other studies have shown that empathy levels among medical students increase or that they are maintained [22,23,24]. Neumann et al. [25] published a systematic review on student empathy in 2011, concluding on the basis of 18 studies that empathy levels decline during medical education due to, mainly, an increase in student-patient contact and interaction. Colliver et al. [26] however, conducting a meta-analysis a year earlier, concluded that student empathy levels only decrease to a minimal degree if at all. Since then, more studies on the subject have been published that assumingly reflect all the new educational initiatives taking in relation to the medical curriculum that have empathy cultivation and preservation as a key goal, such as accompanying patients on medical visits making home visits, and reading medically related literature and poetry (narrative medicine) [27, 28]. Summarising the above, empathy is an important concept in health care and within educational research. However, as a consequence of many different definitions and understandings of empathy, and of different ways of measuring empathy, research in the area has also led to ambiguous results. There is therefore a need for an updated overview and review of the most recent research evidence regarding empathy among medical students.

The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Guidelines (PRISMA) [29] of the literature published between February 2010 and March 2019. We sought to answer the following questions:

- 1.

What are the empathy levels among medical students across the number of educational years?

- 2.

How do levels of empathy relate to gender, specialty preferences, and nationality?

Method

Search strategy

The review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines [29]. AJ and FA conducted a systematic search in March 2019 informed by the research questions. Three databases were searched: PubMed, EMBASE, and PsycINFO. The following search words were used: ‘empathy’ AND ‘medical student’ AND (‘decrease’ OR ‘increase’). Additionally, synonyms, the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Heading terms (MeSH) and subject headings were identified and applied (see Additional file 1). During the full-text screening, we also performed a manual search of reference sections to identify studies not found through the database searches.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were the following:

Studies published between February 2010 and March 2019

Quantitative studies

Studies in English or Scandinavian language

Study population restricted to medical students

Exclusion criteria were the following:

Qualitative studies

Intervention studies

Psychometric studies

Conference abstracts

Non-empirical texts

Selection of data

Titles and abstracts of the studies were screened. In the case of uncertainty, full texts were read. Disagreement between reviewers (AJ and FA) regarding inclusion of the studies was settled through discussion until concordance was reached. Afterwards, AJ and FA read the full texts of the eligible studies. Together, the authors summarised and analysed the methods, results, and discussion sections of the studies. Independently, we applied methodological quality assessment tools on the different studies according to study design. Crombie’s items [30] were applied to cross-sectional studies (n = 24) and consist of seven items rated as “yes” (1 point), “unclear” (0.5 points) and “no” (0 points), with a maximum of 7 points. The quality of the longitudinal studies (n = 6) was assessed by employing a structured 33-point checklist from Tooth et al. (see Additional file 2) [31]. Possible disagreements were discussed and settled and there was inter-rater reliability.

Results

Included studies

The search resulted in 1501 studies, of which 347 were duplicates (see Fig. 1). A total of 1154 studies were screened by title and abstract. Among these, 41 studies were selected for full-text reading since they fulfilled the inclusion criteria. During full-text reading, reference sections were also screened, which revealed another 12 eligible studies. A total of 53 studies were full-text screened. We excluded 23 of the 53 studies since they did not apply to our aim (n = 20) or were in a language other than English or Scandinavian (n = 3). Altogether 30 studies were included in the review.

Study characteristics

Study design and sample sizes

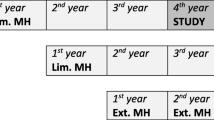

Of the 30 studies included in the review, 24 studies were cross-sectional and 6 studies longitudinal (see study characteristics and main findings in Table 1). Sample sizes of the cross-sectional studies varied from 129 [28] to 5521 [48] participants. In the longitudinal studies, sample size varied from 72 [52] to 1653 [55] participants.

Scales

All cross-sectional studies employed the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy student version (JSPE-S), except for four studies using the following scales: the Basic Empathy Scale [40], Measure of Patient-Centered Communication (MPCC) [28], Reading the Mind in the Eyes (RMET) and Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES) [37], and Empathic Skill Scale Form B and Conflict Tendency Scale [23].

All longitudinal studies used JSPE-S except for one that applied the Interpersonal Reactivity Index scale (IRI) [55]. One longitudinal study applied both an observational Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE) evaluation and JSPE-S [38]. Likewise, a cross-sectional study used the Measure of Patient-Centered Communication (MPCC), which is also an observational scale that measures empathy [28].

Country

The studies were conducted in 20 different countries.

The Western countries were Australia [24], Belgium [40], New Zealand [42, 52], Portugal [32], USA [28, 35, 38, 56], United Kingdom [42, 49, 55].

The non-Western countries were Brazil [43], China [44, 45], Colombia [41, 51], Dominican Republic [41], Ecuador [51], Ethiopia [37], India [36, 39], Iran [21, 46, 47, 50], Korea [48], Kuwait [53], Malaysia [54], Pakistan [33], Trinidad and Tobago [34] and Turkey [23].

Quality assessment and risk of bias in the included studies

The quality assessment tools were used to identify the risk of bias. All included studies employed self-reporting questionnaires. Consequently, reporting bias was present which may have influenced the results. Three studies used small sample sizes, including respectively 129 [28], 77 [32], and 122 [56] study participants Hence, the findings of those studies may not be representative of the student population measured and it might over- and/or underestimate the outcome measures.

Out of 30 studies, 24 were single-institution studies [21, 23, 24, 27, 28, 32, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40, 43,44,45,46, 49, 50, 52,53,54,55,56] making the results of these studies less generalisable and hereby affecting the studies’ external validity.

One obvious limitation of the cross-sectional studies design was their inability to report changes over time. On the contrary, longitudinal studies could describe changes over time. Only one study used a control group of non-medical students, increasing its quality since it enabled comparison.

All studies, except for one [37], employed validated scales to examine the level of empathy. One study [53] employed the English validated JPSE-S on students who did not have English as their native language.

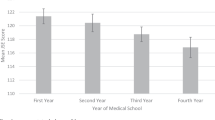

The levels of empathy across number of educational years

Significantly lower levels of empathy by increase in number of educational years were found in 14 out of 30 studies. Of these, 12 were cross-sectional studies [21, 33, 34, 39,40,41, 45,46,47,48, 50, 52, 54] and two were longitudinal [52, 56]. All except one [55] of the cross-sectional studies used JSPE-S. Four cross-sectional studies [23, 27, 28, 44] reported a higher level of empathy among medical students at a higher year of medical school. Five cross-sectional studies [24, 42, 43, 49, 51] and one longitudinal study [32] found no statistically significant difference in empathy scores across the different years of medical education. Hasan et al. [53] reported higher empathy scores with higher educational years up until the fourth year, where a decreasing trend was observed. A cross-sectional study [37] differentiated between emotional and cognitive empathy and found a higher cognitive empathy level in final year students compared to first-year students. On the contrary, a longitudinal study [55] found no change in cognitive empathy.

Chen et al. [38] conducted a longitudinal study, applying both self-administered empathy measures and observed empathy in an OSCE. It showed higher self-administered empathy scores among second-year students compared to third-year students and the opposite for the observed empathy scores. In another longitudinal study by Chen et al. [35] higher levels of empathy were found up to the third-year of education, followed by a persistent decline.

Smith et al. [56] conducted a longitudinal study applying both JSPE-S and the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE). The two scales revealed incongruent results: the QCAE score increased over time while JSPE-S measured a decrease over time.

Gender

Female students were reported to have higher empathy scores compared to male students in 16 cross-sectional and 2 longitudinal studies [21, 24, 27, 34,35,36,37, 39, 40, 42,43,44, 47,48,49,50, 53, 56]. One longitudinal study by Quince et al. [55] found a lower level of emotional empathy among men compared to women who did not show any change. No gender differences were found in relation to cognitive empathy and no differences between genders were detected in seven cross-sectional [23, 28, 33, 41, 45, 46, 54]. Three studies did not investigate the differences in empathy across genders [32, 38, 51].

Specialty preferences

Nine cross-sectional studies investigated a possible relation between empathy scores and specialty preferences of the students [27, 28, 33, 34, 39, 43, 45, 46, 53]. Three studies detected higher levels of empathy among students who preferred a “people-orientated” specialty [28, 43, 45]. No association between specialty preferences and empathy scores was found in the remaining six studies. None of the longitudinal studies examined specialty preferences.

Western and non-Western countries

Out of the thirty studies, nine cross-sectional studies that all applied JSPE-S, from India [36, 39], Kuwait [53], China [44, 45], Korea [48], Iran [46, 50] and Pakistan [33], reported lower mean empathy scores compared to Western countries.

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review aimed to investigate the level of empathy among medical students across the educational years and how the measured empathy levels relate to gender, specialty preferences, and nationality. In reviewing studies from 20 different countries, variations were found in the level of empathy among medical students across the number of educational years. Nearly half of the included studies [21, 33, 34, 39,40,41, 45,46,47,48, 50, 52, 54, 56], of which only two [52, 56] were longitudinal, reported lower empathy scores with higher educational years. The remaining 17 studies [23, 24, 27, 28, 32, 35,36,37,38, 42,43,44, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56] identified both higher, mixed or unchanged levels of empathy throughout the medical education.

Most studies [21, 24, 27, 34,35,36,37, 39, 40, 42,43,44, 47,48,49,50, 53, 55, 56] found a tendency towards higher levels of empathy among female students as compared to male students. Out of nine cross-sectional studies, only three [28, 43, 45] reported an association between empathy and specialty preferences. Furthermore, studies from non-Western countries reported a lower level of mean empathy scores as compared to Western countries. These findings thus differed from the previous review by Neumann et al. [25] which concluded that empathy decreases by an increase in the educational years particularly among those preferring “non-people-orientated” specialities. While different results might be explained by differences in study populations, study design (longitudinal vs cross-section), the instrument used, local culture, etc., this review tells us that we cannot make the often quoted statement that “empathy declines with level of training”.

Possible explanations for lower and higher levels of empathy

In the literature, several explanations for a decline in empathy have been discussed without demonstrating a clear causal relationship. Some scholars point to the phenomenon of burnout among medical students and refer to the association found in the literature between high burnout level among medical students and low empathy score [65,66,67]. Related, stress among medical students [68,69,70] has also been shown to correlate negatively with empathy [69]. Another explanation put forward in the literature for empathy decline is increased patient contact during clinical training [34, 35, 38, 45, 46, 50, 52]. Chen et al. [38] explained the development towards lower levels of empathy during clinical training as a result of an acculturation process in which superiors and mentors try to protect their students against psychological distress by cultivating a climate of cynicism, emotional distance and detachment among medical students in their contact with patients and at the same time try to safeguard “professionalism” in the clinical setting. Moreover, Li et al. [45] stated that clinical training might encompass intense patient-physician relationships, long working hours and sleep deprivation, leading to lower levels of empathy after clinical training. Furthermore, in the literature, the so-called “hidden curriculum,” lack of role models, fear and anxiety in the meeting with the patients, and increased workload are also pointed out as possible reasons for a decline in empathy [46, 71, 72]. Another explanation mentioned in the literature is that the medical curriculum focuses more on diagnosis and treatment than humanistic values [73]. Shapiro et al. [71] also stated that the biomedical discourse has diverted the students’ focus from empathy leading him/her to adopt a mechanistic view on illness that might reduce the patients to a disease or an object.

Discussing the increases in empathy levels that were documented in some of the reviewed studies, Magalhaes et al. [27] pointed out that the medical curriculum has an increased focus on the development of empathy as the educational years progress and that students have increasingly reached an acknowledgment of the importance of empathy in the patient-physician relationship. This point of view was put forward as a possible explanation for the documented increases in empathy. Furthermore, training and competence acquirement through clinical training of communication skills have also been proposed as an explanation for the tendency towards higher levels of empathy in senior year medical students [27, 28]. In relation to these explanations it should also be kept in mind that the medical curriculum varies across countries and medical schools.

Gender differences

In the literature, varying explanations for gender differences are suggested. Bertakis et al. [16] found that females are more receptive to emotional signals than males. Furthermore, they are said to show more interest in the patient’s family and social life, thereby being able to achieve a better understanding of the patient and reach a more empathic relation. Shashikumar et al. [39] stated that females through evolutionary gender differences are more caring and loving.

Nationalities

Nine studies in our systematic review reported a propensity towards lower empathy scores in non-Western compared to Western countries. All of these studies applied the JSPE-S. Shariat et al. [47] stated that awareness of the cultural differences should be kept in mind when applying the JSPE-S in cultures that differ from the USA, where the JSPE-S was developed. A Japanese psychometric study of the JSPE pointed out that Japanese patients preferred their physician to be calm and unemotional, emphasising that cultural differences could indeed explain the differences in empathy scores between countries and cultures [74].

Specialty preferences

A possible association between levels of empathy and specialty preferences was investigated in nine of the included studies [27, 28, 33, 34, 39, 43, 45, 46, 53]. Only three studies [28, 43, 45] reported an association between higher level of empathy among people preferring “people-orientated” specialities. Engaging in an empathic understanding of the patients’ feelings and life circumstances is important in all medical specialities since showing an empathic attitude towards the patient has been shown to lead to positive effects on patients’ health outcome [8, 9]. It can be argued, however, that a focus on empathy is relevant mostly within people-orientated specialities since physicians who work in these specialities are both in need of help regarding empathy preservation (helping patients) and administration (helping themselves so as to decrease the risk of stress and burn-out) [3].

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the present systematic review is that the literature search was conducted in three databases. Furthermore, the screening of literature and selection of studies was performed by two reviewers. Moreover, we consider the implementation of a quality assessment of all included studies as a strength. This review has several limitations. Since our search words included words that presume a change e.g. “decrease” and “increase,” our search may be too narrow, and there is a risk that relevant studies have been overlooked. Additionally, possible relevant studies in languages other than English and Scandinavian were not included. Another limitation is that only quantitative studies were included. This excluded qualitative aspects that could have contributed to a more varied and profound understanding of the quantitative findings.

Future research

Most of the included studies applied the self-administered JSPE-S and therefore did not explore the display of empathy that takes place between the patient and the medical student. Sulzer et al. [75] stated that the JSPE-S scale focuses on thoughts and not actions. Furthermore, research has shown that self-reported empathy has only a vague association with the patient-physician relationship in the clinical setting [75]. To improve the knowledge of empathy among medical students, research that includes both cognition, action, and feelings is recommended [75]. Incorporation of non-medical students as control groups is also required in order to gain more insight into whether medical students’ levels of empathy differ compared to other university students. Furthermore, future investigators should employ a variety of research designs to investigate the important role of empathy in medical education, such as mixed methods research, observational research, and qualitative research. These studies could focus - not on self-reporting – but rather on patient perceptions of empathic student/physician behaviour. Qualitative research conducted with students could also contribute to new perspectives and insights about student-perceived factors influencing the development of empathy and its expression in clinical care. Lastly, a meta-analysis is desirable since it enables the calculation of statistical significance and heterogeneity.

Conclusions

This systematic review including thirty studies, revealed varied and inconsistent findings on the levels of empathy among medical students. Statistically lower empathy scores by an increase in educational years were found in 14 studies. The remaining studies reported higher [4] and unchanged [6] scores in empathy. In most studies, females were reported to have higher levels of empathy than males. Study participants from non-Western countries reported a tendency towards lower mean empathy scores as compared to those from Western countries. Only a few studies reported a correlation between “people-oriented” specialty preferences and empathy scores. Future research should focus on examining relational empathy in student-patient interaction using observational scales and qualitative methodologies.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- BEES:

-

Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale

- CARE:

-

Consultation-and-Relational-Empathy

- IRI:

-

Interpersonal Reactivity Index scale

- JSPE:

-

Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy

- JSPE-S:

-

Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy student version

- LDL:

-

Lipoprotein cholesterol

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Heading terms

- MPCC:

-

Measure of Patient-Centered Communication

- OSCE:

-

Objective Structured Clinical Examinations

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- QCAE:

-

Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy

- RMET:

-

Reading the Mind in the Eyes

References

MacKay R, Hughes JR, Carver EJ. Empathy in the helping relationship. New York: Springer; 1990.

Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(Suppl):S9–12.

Hojat M. Empathy in health professions education and patient care. Swizterland: Springer; 2007.

Sadati AK, Tabei SZ, Lankarani KB. A qualitative study on the importance and value of doctor-patient relationship in Iran: physicians’ views. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(10):1895–901.

Derksen F, Bensing J, Kuiper S, van Meerendonk M, Lagro-Janssen A. Empathy: what does it mean for GPs? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2015;32(1):94–100.

Derksen F, Olde Hartman TC, van Dijk A, Plouvier A, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Consequences of the presence and absence of empathy during consultations in primary care: a focus group study with patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(5):987–93.

Squier RW. A model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner-patient relationships. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(3):325–39.

Steinhausen S, Ommen O, Thum S, Lefering R, Koehler T, Neugebauer E, et al. Physician empathy and subjective evaluation of medical treatment outcome in trauma surgery patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(1):53–60.

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359–64.

Renzi C, Abeni D, Picardi A, Agostini E, Melchi CF, Pasquini P, et al. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145(4):617–23.

Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237–51.

Mercer SW, Watt GC, Reilly D. Empathy is important for enablement. BMJ. 2001;322(7290):865.

Larson EB, Yao X. Clinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 2005;293(9):1100–6.

Thirioux B, Birault F, Jaafari N. Empathy is a protective factor of burnout in physicians: new neuro-phenomenological hypotheses regarding empathy and sympathy in care relationship. Front Psychol. 2016;7:763.

Hojat M, Zuckerman M, Gonnella JS, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Vergare MJ, et al. Empathy in medical students as related to specialty interest, personality, and perception of mother and father. Personal Individ Differ. 2005;39:1205–15.

Bertakis KD, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Azari R, Robbins JA. The influence of gender on physician practice style. Med Care. 1995;33(4):407–16.

Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: a critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:497–519.

Shanafelt TD, West C, Zhao X, Novotny P, Kolars J, Habermann T, et al. Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced empathy among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):559–64.

Ferreira-Valente A, Monteiro JS, Barbosa RM, Salgueira A, Costa P, Costa MJ. Clarifying changes in student empathy throughout medical school: a scoping review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;22(5):1293–313.

Chen D, Lew R, Hershman W, Orlander J. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(10):1434–8.

Khademalhosseini M, Khademalhosseini Z, Mahmoodian F. Comparison of empathy score among medical students in both basic and clinical levels. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2014;2(2):88–91.

Todres M, Tsimtsiou Z, Stephenson A, Jones R. The emotional intelligence of medical students: an exploratory cross-sectional study. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):e42–8.

Atay IM, Sari M, Demirhan M, Aktepe E. Comparison of empathy skills and conflict tendency in preclinical and clinical phase Turkish medical students: a cross-sectional study. Dusunen Adam. 2014;27(4):308–15.

Hegazi I, Wilson I. Maintaining empathy in medical school: it is possible. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):1002–8.

Neumann M, Edelhauser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):996–1009.

Colliver JA, Conlee MJ, Verhulst SJ, Dorsey JK. Reports of the decline of empathy during medical education are greatly exaggerated: a reexamination of the research. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):588–93.

Magalhaes E, Salgueira AP - Costa P, Costa MJ. Empathy in senior year and first year medical students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 2011;11(52):1472–6920.

Teng VC, Nguyen C, Hall KT, Rydel T, Sattler A, Schillinger E, et al. Rethinking empathy decline: results from an OSCE. Clin Teach. 2017;14(6):441–5.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8(1):2–10.

Tooth L, Ware R, Bain C, Purdie DM, Dobson A. Quality of reporting of observational longitudinal research. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(3):280–8.

Costa P, Magalhaes E, Costa MJ. A latent growth model suggests that empathy of medical students does not decline over time. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013;18(3):509–22.

Tariq N, Rasheed T, Tavakol M. A quantitative study of empathy in Pakistani medical students: a multicentered approach. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8(4):294–9.

Youssef FF, Nunes P, Sa B, Williams S. An exploration of changes in cognitive and emotional empathy among medical students in the Caribbean. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:185–92.

Chen DC, Kirshenbaum DS, Yan J, Kirshenbaum E, Aseltine RH. Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):305–11.

Chatterjee A, Ravikumar R, Singh S, Chauhan PS, Goel M. Clinical empathy in medical students in India measured using the Jefferson scale of empathy-student version. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2017;14:33.

Dehning S, Girma E, Gasperi S, Meyer S, Tesfaye M, Siebeck M. Comparative cross-sectional study of empathy among first year and final year medical students in Jimma University, Ethiopia: steady state of the heart and opening of the eyes. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:34.

Chen DC, Pahilan ME, Orlander JD. Comparing a self-administered measure of empathy with observed behavior among medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):200–2.

Shashikumar R, Chaudhary R, Ryali VS, Bhat PS, Srivastava K, Prakash J, et al. Cross sectional assessment of empathy among undergraduates from a medical college. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70(2):179–85.

Triffaux JM, Tisseron S, Nasello JA. Decline of empathy among medical students: dehumanization or useful coping process? Encephale. 2019;45(1):3–8.

Diaz Narvaez VP, Alonso Palacio LM, Caro SE, Silva MG, Castillo JA, Bilbao JL, et al. Empathic orientation among medical students from three universities in Barranquilla, Colombia and one university in the Dominican Republic. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2014;112(1):41–9.

Quince TA, Kinnersley P, Hales J, da Silva A, Moriarty H, Thiemann P, et al. Empathy among undergraduate medical students: a multi-centre cross-sectional comparison of students beginning and approaching the end of their course. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(92):016–0603.

Santos MA, Grosseman S, Morelli TC, Giuliano IC, Erdmann TR. Empathy differences by gender and specialty preference in medical students: a study in Brazil. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:149–53.

Wen D, Ma X, Li H, Liu Z, Xian B, Liu Y. Empathy in Chinese medical students: psychometric characteristics and differences by gender and year of medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(130):1472–6920.

Li D, Xu H, Kang M, Ma SA-OA-OX. Empathy in Chinese eight-year medical program students: differences by school year, educational stage, and future career preference. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):018–1348.

Benabbas R. Empathy in Iranian medical students: a comparison by age, gender, academic performance and specialty preferences. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2016;30:439.

Shariat SV, Habibi M. Empathy in Iranian medical students: measurement model of the Jefferson scale of empathy. Med Teach. 2013;35(1):3.

Park KH, Roh H, Suh DH, Hojat M. Empathy in Korean medical students: findings from a nationwide survey. Med Teach. 2015;37(10):943–8.

Tavakol S, Dennick R, Tavakol M. Empathy in UK medical students: differences by gender, medical year and specialty interest. Educ Prim Care. 2011;22(5):297–303.

Rezayat AA, Shahini N, Asl HT, Jarahi L, Behdani F, Shojaei SRH, et al. Empathy score among medical students in Mashhad, Iran: study of the Jefferson scale of physician empathy. Electron Physician. 2018;10(7):7101–6.

Calzadilla-Nunez A, Diaz-Narvaez VP, Davila-Ponton Y, Aguilera-Munoz J, Fortich-Mesa N, Aparicio-Marenco D, et al. Erosion of empathy during medical training by gender. A cross-sectional study. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115(6):556–61.

Lim BT, Moriarty H - Huthwaite M, Gray L, Pullon S, Gallagher P. How well do medical students rate and communicate clinical empathy? Med Teach. 2013;35(2):3.

Hasan S, Al-Sharqawi N, Dashti F, AbdulAziz M, Abdullah A, Shukkur M, Bouhaimed M, et al. Level of empathy among medical students in Kuwait University, Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22(4):385–9.

Williams B, Sadasivan S, Kadirvelu A. Malaysian medical students’ self-reported empathy: a cross-sectional comparative study. Med J Malaysia. 2015;70(2):76–80.

Quince TA, Parker RA, Wood DF, Benson JA. Stability of empathy among undergraduate medical students: a longitudinal study at one UK medical school. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(90):1472–6920.

KEA-Ohoo S, Norman GJ, Decety J. The complexity of empathy during medical school training: evidence for positive changes. Med Educ. 2017;51(11):1146–59.

Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Rattner S, Erdmann JB, Gonnella JS, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ. 2004;38(9):934–41.

Magalhaes E, Salgueira A, Gonzalez A-J, Costa JJ, Costa MJ, Costa P, et al. Psychometric properties of a short personality inventory in Portuguese context. [references]. Psicologia: Reflexao e Critica Vol 2014;27(4):642–57.

Hojat M, Mangione S, Kane GC, Gonnella JS. Relationships between scores of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE) and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Med Teach. 2005;27(7):625–8.

Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44(1):113–26.

Aluja A, Rossier J, Garcia LF, Angleitner A, Kuhlman M, Zuckerman M. A cross-cultural shortened form of the ZKPQ (ZKPQ-50-cc) adapted to English, French, German, and Spanish languages. [references]. Personal Individ Differ. 2006;41(4):619–28.

Cohen S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. Spacapan, Shirlynn [Ed]. 1988.

Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1516–28.

Reniers RL, Corcoran R, Drake R, Shryane NM, Vollm BA. The QCAE: a questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy. J Pers Assess. 2011;93(1):84–95.

Brazeau CM, Schroeder R, Rovi S, Boyd L. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med. 2010;85(10 Suppl):S33–6.

Thomas MR, Dyrbye LN, Huntington JL, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, et al. How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? A multicenter study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):177–83.

Holmes CL, Miller H, Regehr G. (Almost) forgetting to care: an unanticipated source of empathy loss in clerkship. Med Educ. 2017;51(7):732–9.

Ludwig AB, Burton W, Weingarten J, Milan F, Myers DC, Kligler B. Depression and stress amongst undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:141.

Park KH, Kim DH, Kim SK, Yi YH, Jeong JH, Chae J, et al. The relationships between empathy, stress and social support among medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:103–8.

Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Durning SJ, Moutier C, Thomas MR, Massie FS Jr, et al. Patterns of distress in US medical students. Med Teach. 2011;33(10):834–9.

Shapiro J. Walking a mile in their patients’ shoes: empathy and othering in medical students’ education. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008;3:10.

Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1182–91.

Morse DS, Edwardsen EA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(17):1853–8.

Kataoka HU, Koide N, Ochi K, Hojat M, Gonnella JS. Measurement of empathy among Japanese medical students: psychometrics and score differences by gender and level of medical education. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1192–7.

Sulzer SH, Feinstein NW, Wendland CL. Assessing empathy development in medical education: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2016;50(3):300–10.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AJ and FA participated in the design of the study, developed the search strategy, extracted the data and drafted the manuscript. CMA and EAH participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors (AJ, FA, JS, EAH, CMA) declare that they have read and approved the final manuscript. AJ and FA: graduate medical students. JS, CMA and EAH: senior researchers.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search protocol. Overview of the search strategy employed in the following databases PubMed, Embase and PsycINFO.

Additional file 2.

Methodological quality assessment of the included studies. Above each table the type of quality assessment tool is indicated. In the first table (with overview of the longitudinal studies) the criterions appear in the left column and for each included study there is answered “yes” or “no” to these criterions. In the second table (with overview of the cross-sectional studies) the studies appear in the left column and the criteria items in the first row of the table. The quality assessment tool here is indicated with 0, 0.5 or 1 point per item. The total score is indicated in the right column.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, F.A., Johansen, AS.B., Søndergaard, J. et al. Revisiting the trajectory of medical students’ empathy, and impact of gender, specialty preferences and nationality: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ 20, 52 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-1964-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-1964-5