Abstract

Background

Non-parasitic splenic cysts are associated with elevated serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19–9 levels. We report a case in which a 23-year-old female exhibited a large ruptured splenic cyst and an elevated serum CA19–9 level.

Case presentation

The patient, who experienced postprandial abdominal pain and vomiting, was transferred to our hospital and was found to have a large splenic cyst during an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan. On physical examination, her vital signs were stable, and she demonstrated rebound tenderness in the epigastric region. An abdominal CT scan revealed abdominal fluid and a low-density region (12 × 12 × 8 cm) with enhanced margins in the spleen. The patient’s serum levels of CA19–9 and CA125 were elevated to 17,580 U/mL and 909 U/mL, respectively. A cytological examination of the ascitic fluid resulted in it being categorized as class II. Finally, we made a diagnosis of a ruptured splenic epidermoid cyst and performed laparoscopic splenic fenestration. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged on postoperative day 5. The cystic lesion was histopathologically diagnosed as a true cyst, and the epithelial cells were positive for CA19–9. Follow-up laboratory tests performed at 4 postoperative months showed normal CA19–9 (24.6 U/L) and CA125 (26.8 U/L) levels. No recurrence of the splenic cyst was detected during the 6 months after surgery.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic fenestration of a ruptured splenic cyst was performed to preserve the spleen, after the results of abdominal fluid cytology and MRI were negative for malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Non-parasitic splenic cysts can be asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms, e.g., pain in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen or increasing abdominal girth [1, 2]. Occasionally, splenic cysts cause complications, such as infections, rupturing, or bleeding. Recent studies have reported that non-parasitic splenic cysts are associated with elevated serum and intracystic levels of carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19–9), CA125, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) [3]. A few cases of malignant cystic splenic tumors that presented as splenic cysts have been reported [4, 5]. It is difficult to distinguish between large benign splenic cysts and malignant lesions in cases involving elevated serum and abdominal fluid levels of CA19–9. Here, we report a case in which a young female presented with a large ruptured splenic cyst together with elevated serum CA19–9 and CA125 levels.

Case presentation

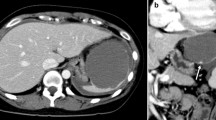

A previously healthy 23-year-old female complained of the sudden onset of abdominal pain and vomiting after eating supper and drinking alcohol. She presented to her local hospital’s emergency department. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a collapsed cystic lesion and abdominal fluid. A ruptured splenic cyst was suspected, and so the patient was referred to our hospital. On arrival, the patient complained of upper abdominal pain. She stated that she had not suffered any diarrhea, hematemesis, or trauma, nor had she recently come into contact with any sick individuals or gone travelling. She was not taking any regular medication and had no relevant family medical history. She had a slightly elevated temperature (37.3 °C), but the rest of her vital signs were normal. An abdominal examination revealed rebound tenderness in the epigastric region. The initial laboratory tests demonstrated an elevated white blood cell count (18.4 × 103 /L) (predominantly due to increased numbers of neutrophils) and increased serum amylase levels (162 U/L), together with normal hemoglobin and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. A coagulation screen produced normal results. However, the following tumor marker level measurements were obtained: CA19–9: 17580 U/L (normal: < 37 U/mL), CA125: 909.8 U/L (normal: < 35 U/mL), CEA: 2.5 ng/mL (normal: 5.3 ng/mL), and interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R): 389 U/L (normal: < 530 U/L). An ascitic tap was obtained, which revealed the following results: lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): 904 U/L, serum total protein (TP): 5.0 g/dL, CA19–9: 490000 U/L, CA125: 24560 U/L, and CEA: 60.6 ng/mL (Table 1). Abdominal fluid cytology revealed no evidence of malignancy. An abdominal CT scan showed a collapsed cystic lesion, measuring 12 × 12 × 8 cm, in the spleen and abdominal fluid in Morison’s pouch and around the liver and spleen. Moreover, an 8-mm cyst and a small collapsed cystic lesion were found posterior to the large cystic splenic lesion. No masses were found in the liver, pancreas, kidneys, or gastrointestinal tract. There was no evidence of contrast medium extravasation (Fig. 1). Based on these results, we excluded a ruptured spleen and made a diagnosis of a ruptured splenic cyst. The differential diagnoses for ruptured epidermoid cysts include splenic pseudocyst, lymphangioma, primary mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, splenic lymphoma, and metastatic tumors. Cystic Echinococcosis were denied because she had denied any history of traveling abroad. There was no evidence of massive hemorrhaging, and an additional contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was obtained on the following day. It showed a cystic lesion, which exhibited slightly hyperintense signals on the T1- and diffusion-weighted sequences and hyperintense signals on the T2-weighted sequence. No solid components or mural cysts were found in the cyst (Fig. 2).

An abdominal CT scan showed a collapsed cystic lesion, measuring 12 cm × 12 cm × 8 cm, in the spleen and abdominal fluid in Morison’s pouch and around the liver and spleen (a). Moreover, an 8-mm cyst and a small collapsed cystic lesion were found posterior to the large cystic lesion on a contrast-enhanced CT scan (b). There was no evidence of contrast medium extravasation (c)

After one week, we removed the splenic cyst via laparoscopic fenestration. Exploration of the surgical field revealed abdominal fluid. The cyst was located at the upper pole of the spleen. We dissected the part of the greater omentum that had adhered to the cyst wall, drained the cyst cavity, and fenestrated the splenic cyst wall using an ultrasonic scalpel, before cauterizing the interior of the cyst wall (Fig. 3). The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course and was discharged on postoperative day 5.

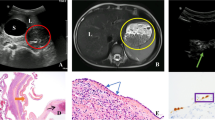

A pathological examination revealed an epidermoid cyst. The cyst wall consisted of fibrous tissue and was lined by a single layer or several layers of squamous epithelium. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the epithelial cells were positive for CA19–9 and CEA (Fig. 4). The patient’s serum levels of CA19–9 and CA125 were 1024 U/mL and 199 U/mL, respectively, at 2 weeks after surgery and had returned to normal at 4 postoperative months (Table 2). A follow-up abdominal CT scan performed at 6 postoperative months did not show any recurrence. The patient was healthy at 15 postoperative months.

Pathological diagnosis of the resected specimen (Hematoxylin and eosin stain and immunohistochemistry of CA19–9 and CEA). The cyst wall consisted of fibrous tissue and was lined by a single layer or several layers of squamous epithelium (a). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the epithelial cells were positive for CA19–9 (b) and CEA (c) (4A, 4B and 4C: × 400)

Discussion and conclusion

The preoperative diagnosis was a ruptured non-parasitic splenic cyst. Cystic Echinococcosis were ruled out by her social history. In Japan, cystic Echinococcosis is very rare disorders, except for imported cases [6] and hydatid serological testing may be indicated in patients who have been to an endemic area of Echinococcosis. Major problem is to differentiate epidermoid cysts from malignant lesions in cases involving elevated serum levels of tumor markers. The sensitivity of abdominal fluid cytology for malignant ascites is about 60 to 70% with 90 to 100% specificity and 11.7% (26/222) of negative cytology cases have a malignant tumor [7].

To the best of our knowledge, 51 cases of splenic cysts involving high levels of tumor markers have been reported, not including accessory spleens [1, 3, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] (Table 3). Of 50 cases, 76% were female (38 cases). The mean age was 28 years old (range: 9–62). No parasitic splenic cysts cases involving elevated tumor markers were found. Including our case, only 4 cases of ruptured splenic cysts have been reported [15, 24, 28]. All of these cases involved abdominal pain. One case involved traumatic rupture [24]. Only one of the patients with ruptured splenic cysts developed peritonitis, which required emergency laparotomy, and purulent ascites was detected, but the route by which splenic cysts become infected is unknown [28]. Among the 51 cases, the mean size of the ruptured cysts was 12.6 cm, while that of the unruptured cysts was 12.7 cm (range: 3–25). The cases involving ruptured cysts demonstrated higher serum CA19–9 levels than those involving unruptured cysts (21,199 U/L vs. 2907 U/L, respectively). However, there was no correlation between cyst size and the serum CA19–9 level (r = − 0.057). The postoperative serum levels of tumor markers were not mentioned in 4 cases, whereas they decreased after treatment in 47 cases. The tumor marker levels of 38 of the 47 cases subsequently normalized. These findings suggest that measuring the serum CA19–9 level is useful for evaluating the effects of treatments for splenic epidermoid cysts. Four patients experienced recurrence after the following treatments: surgery (2 cases) [27, 37], percutaneous drainage alone (one case) [11], and percutaneous drainage and sclerotherapy (one case) [9]. The serum CA19–9 levels before and after recurrence were not mentioned in 4 cases, so it is unclear whether measuring the serum CA19–9 level is useful for evaluating recurrence.

The mechanism responsible for the elevated tumor marker levels seen in such cases remains unclear. The intracystic and serum CA19–9 levels were high in most cases, but the CEA levels were markedly elevated in the cystic fluid whereas normal in the serum in some cases [27, 28, 32]. The inner epithelial cells of splenic cysts were immunohistochemically positive for CA19–9 in most cases and CEA in some cases [15, 18], so they can produce tumor markers and over time these markers become concentrated in the cysts, which are closed cavities. Tumor markers are secreted into the bloodstream via an unknown mechanism. If a cyst ruptures, the serum levels of tumor markers increase because the cystic fluid containing the markers is absorbed through the peritoneum.

Large, symptomatic, or complex cysts are indicated for treatment. Large cysts are susceptible to rupture and can cause other complications. According to some previous reports, cysts measuring ≥5 cm in diameter are indicated for surgical intervention, but there is a lack of evidence for this 5-cm cut-off point, and cyst size is generally not used as a cause for intervention [42].

The treatments for ruptured splenic cysts include percutaneous drainage, splenectomy, partial splenectomy, marsupialization, and fenestration. Percutaneous aspiration therapy alone is associated with low success and high recurrence rates [11]. Percutaneous aspiration combined with the injection of sclerosing substances (e.g., tetracycline, minocycline, or ethanol) is used to prevent recurrence. Percutaneous ethanol ablation is associated with high success rates, but the associated recurrence rates vary [39, 43]. Surgical intervention is recommended in symptomatic or complicated cases [44]. Splenectomy can prevent recurrence, but carries a risk of postoperative infection and thrombocytosis. Epidermoid cysts predominantly occur in young females. Thus, spleen-preserving surgery (such as laparoscopic fenestration, marsupialization, or dome resection) has been suggested, especially for cysts located at the poles of the spleen. The resection of the cyst wall and the cauterization of the rest of the cyst wall are recommended to avoid recurrence [11]. Splenectomy was performed in all 3 of the previously reported cases of ruptured cysts with elevated serum CA19–9 levels. In the present case, laparoscopic fenestration of the splenic cyst, rather than laparoscopic splenectomy, was selected because the results of cytology and MRI are negative for malignancy.

Abbreviations

- CA:

-

carbohydrate antigen

- CEA:

-

carcinoembryonic antigen

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- IL-2R:

-

interleukin-2 receptor

- LDH:

-

lactate dehydrogenase

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- TP:

-

total protein

References

Trompetas V, Panagopoulos E, Priovolou-Papaevangelou M, Ramantanis G. Giant benign true cyst of the spleen with high serum level of CA 19-9. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14(1):85–88. PubMed PMID: 11782581.

Ingle SB, Hinge Ingle CR, Patrike S. Epithelial cysts of the spleen: a minireview. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20(38):13899–13903. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13899. PubMed PMID: 25320525; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4194571.

Walz MK, Metz KA, Sastry M, Eigler FW, Leder LD. Benign mesothelial splenic cyst may cause high serum concentration of CA 19-9. Eur J Surg 1994;160(6–7):389–391. PubMed PMID: 7948360.

Elit L, Aylward B. Splenic cyst carcinoma presenting in pregnancy. Am J Hematol 1989;32(1):57–60. PubMed PMID: 2667342.

Ballestri S, Lonardo A, Romagnoli D, Losi L, Loria P. Primary lymphoma of the spleen mimicking simple benign cysts: contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and other imaging findings. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2015;42(2):251–255. Epub 2014/10/04. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-014-0579-z. PubMed PMID: 26576581.

Nakamura K, Ito A, Yara S, Haranaga S, Hibiya K, Hirayasu T, et al. A case of pulmonary and hepatic cystic echinococcosis of CE1 stage in a healthy Japanese female that was suspected to have been acquired during her stay in the United Kingdom. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011;85(3):456–459. doi: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0112. PubMed PMID: 21896804; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3163866.

Motherby H, Nadjari B, Friegel P, Kohaus J, Ramp U, Böcking A. Diagnostic accuracy of effusion cytology. Diagn Cytopathol 1999;20(6):350–357. PubMed PMID: 10352907.

Terada T, Yasoshima M, Yoshimitsu Y, Nakanuma Y. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 producing giant epithelial cyst of the spleen in a young woman. J Clin Gastroenterol 1994;18(1):57–61. PubMed PMID: 8113588.

Yoshikane H, Suzuki T, Yoshioka N, Ogawa Y, Hayashi Y, Hamajima E, et al. Giant splenic cyst with high serum concentration of CA 19-9. Failure of treatment with percutaneous transcatheter drainage and injection of tetracycline. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;31(5):524–526. PubMed PMID: 8734353.

Higaki K, Jimi A, Watanabe J, Kusaba A, Kojiro M. Epidermoid cyst of the spleen with CA19-9 or carcinoembryonic antigen productions: report of three cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22(6):704–708. PubMed PMID: 9630177.

Sardi A, Ojeda HF, King D. Laparoscopic resection of a benign true cyst of the spleen with the harmonic scalpel producing high levels of CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen. Am Surg 1998;64(12):1149–1154. PubMed PMID: 9843333.

Ishibashi R, Sakai T, Yamashita Y, Maekawa T, Hideshima T, Shirakusa T. Benign epithelial cyst of the spleen with a high production of carbohydrate antigen 19-9. Int Surg 1999;84(2):151–154. PubMed PMID: 10408287.

Sakamoto Y, Yunotani S, Edakuni G, Mori M, Iyama A, Miyazaki K. Laparoscopic splenectomy for a giant splenic epidermoid cyst: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29(12):1268–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02482221. PubMed PMID: 10639710.

van Lacum MW, Hessels RA, Kremer GD, Jaspers CA. A splenic cyst and a high serum CA 19-9: a case report. Eur J Intern Med 2000;11(2):104–107. PubMed PMID: 10745156.

Matsubayashi H, Kuraoka K, Kobayashi Y, Yokota T, Iiri Y, Shichijo K, et al. Ruptured epidermoid cyst and haematoma of spleen: a diagnostic clue of high levels of serum carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and Sialyl Lewis x. Dig Liver Dis 2001;33(7):595–599. PubMed PMID: 11816551.

Soudack M, Ben-Nun A, Toledano C. Elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9 in patients with true (epithelial) splenic cysts--rare or undiscovered? Can J Gastroenterol 2001;15(2):125–126. PubMed PMID: 11240382.

Ito Y, Shimizu E, Miyamoto T, Taniguchi T, Nakajima K, Hara T, et al. Epidermoid cysts of the spleen occurring in sisters. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47(3):619–623. PubMed PMID: 11911352.

Lieto E, Castellano P, Ferraraccio F, Orditura M, De Vita F, Romano C, et al. Normal interleukin-10 serum level opposed to high serum levels of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and cancer antigens 125 and 50 in a case of true splenic cyst. Arch Med Res. 2003;34(2):145–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0188-4409(02)00468-X. PubMed PMID: 12700012.

Madia C, Lumachi F, Veroux M, Fiamingo P, Gringeri E, Brolese A, et al. Giant splenic epithelial cyst with elevated serum markers CEA and CA 19-9 levels: an incidental association? Anticancer Res 2003;23(1B):773–776. PubMed PMID: 12680182.

Yagi S, Isaji S, Iida T, Mizuno S, Tabata M, Yamagiwa K, et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy for a huge splenic cyst without preoperative drainage: report of a case. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2003;13(6):397–400. PubMed PMID: 14712105.

Hashimoto T, Sugino T, Fukuda T, Hoshi N, Ogura G, Watanabe K, et al. Multiple epithelial cysts of the spleen and on the splenic capsule, and high serum levels of CA19-9, CA125 and soluble IL-2 receptor. Pathol Int. 2004;54(5):349–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01630.x. PubMed PMID: 15086840.

Arda IS, Tüzün M, Hicsönmez A. Epidermoid cyst of the spleen with elevated levels of CA125 and carcino-embryonic antigen. Eur J Pediatr 2005;164(2):108. Epub 2004/12/03. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-003-1236-5. PubMed PMID: 15580359.

Chiarugi M, Galatioto C, Battini A, Panicucci S, Lippolis P, Seccia M. Giant epidermoid cyst of the spleen with carbohydrate and cancer antigen production managed laparoscopically. Ann Ital Chir 2006;77(5):443–446. PubMed PMID: 17345995.

Kubo M, Yamane M, Miyatani K, Udaka T, Mizuta M, Shirakawa K. Familial epidermoid cysts of the spleen: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2006;36(9):853–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-006-3244-3. PubMed PMID: 16937296.

Paksoy M, Karabicak I, Kusaslan R, Demiryas S, Ayan F, Ertem M. Laparoscopic splenic total cystectomy in a patient with elevated CA 19-9. JSLS. 2006;10(4):507–510. PubMed PMID: 17575768; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3015757.

Yigitbasi R, Karabicak I, Aydogan F, Erturk S, Bican O, Aydin O, et al. Benign splenic epithelial cyst accompanied by elevated ca 19-9 level: a case report. Mt Sinai J Med 2006;73(6):871–873. PubMed PMID: 17117313.

Chihaya K, Hayashi T, Mishima T, Isomoto I, Mochizuki K, Hamada T, et al. Laparoscopic marsupialization surgery for large epidermoid cyst of spleen in a child. Acta Med Nagasaki. 2007;52:63–6.

Inokuma T, Minami S, Suga K, Kusano Y, Chiba K, Furukawa M. Spontaneously Ruptured Giant Splenic Cyst with Elevated Serum Levels of CA 19–9, CA 125 and Carcinoembryonic Antigen. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4(2):191–197. Epub 2010/06/11. https://doi.org/10.1159/000315559. PubMed PMID: 20805943; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2929414.

Papadopoulos IN, Davatzikos A, Kasabalis G, Manti C, Konstantoudakis G. Primary epithelial splenic cyst with micro-rupture and raised carbohydrate antigen CA 19–9: a paradigm of management. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010. Epub 2010/11/02. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.06.2010.3125. PubMed PMID: 22791783; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3029511.

Brauner E, Person B, Ben-Ishay O, Kluger Y. Huge splenic cyst with high level of CA 19-9: the rule or the exception? Isr Med Assoc J 2012;14(11):710–1. PubMed PMID: 23240382.

Graziani G, Cucchiari D, Podestà MA, Quagliuolo V, Montanelli A. Abdominal pain and increased CA19-9. Clin Chem 2013;59(11):1678–1679. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2013.203885. PubMed PMID: 24167189.

Hoshino A, Nakamura Y, Suzuki H, Mizutani S, Chihara N, Matsunobu T, et al. Giant epidermoid cyst of the spleen with elevated CA 19-9 production managed laparoscopically: report of a case. J Nippon Med Sch 2013;80(6):470–474. PubMed PMID: 24419721.

Vo QD, Monnard E, Hoogewoud HM. Epidermoid cyst of the spleen. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. Epub 2013/05/09. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-009707. PubMed PMID: 23667225; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3670013.

Yoh T, Wada S, Kobayashi A, Nakamura Y, Kato T, Nakayama H, et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy for a large multilocular splenic cyst with elevated CA19–9: Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(3):319–321. Epub 2013/01/17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.01.003. PubMed PMID: 23399517; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3604669.

Takagi K, Takayama T, Moriguchi M, Hasegawa H, Niide O, Kanamori N, et al. Gastrointestinal: case of accidentally discovered splenic epidermoid cyst with serum CA19-9 elevation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29(2):231. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12495. PubMed PMID: 24460837.

Matsumoto S, Mori T, Miyoshi J, Imoto Y, Shinomiya H, Wada S, et al. Huge splenic epidermoid cyst with elevation of serum CA19-9 level. J Med Investig 2015;62(1–2):89–92. https://doi.org/10.2152/jmi.62.89. PubMed PMID: 25817291.

Cianci P, Tartaglia N, Altamura A, Fersini A, Vovola F, Sanguedolce F, et al. A recurrent epidermoid cyst of the spleen: report of a case and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:98. Epub 2016/04/01. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0857-x. PubMed PMID: 27036391; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4818458.

Matsui T, Matsubayashi H, Sugiura T, Sasaki K, Ito H, Hotta K, et al. A Splenic Epithelial Cyst: Increased Size, Exacerbation of Symptoms, and Elevated Levels of Serum Carcinogenic Antigen 19–9 after 6-year Follow-up. Intern Med. 2016;55(18):2629–2634. Epub 2016/09/15. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6970. PubMed PMID: 27629958.

Yang X, Yu J, Liang P, Yu X, Cheng Z, Han Z, et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous ethanol ablation for primary non-parasitic splenic cysts in 15 patients. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41(3):538–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-015-0584-8. PubMed PMID: 27039325.

Maeda E, Okano K, Suto H, Asano E, Oshima M, Kishino T, et al. Hybrid approach to laparoscopic decapsulation combined with splenic artery balloon occlusion in a patient with carbohydrate antigen 19-9 producing splenic cysts. Asian J Endosc Surg 2017;10(4):459–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/ases.12376. PubMed PMID: 29076276.

Buda N, Wszołek A, Śledziński M, Żawrocki A, Sworczak K. Epidermoid splenic cyst with elevated serum level of CA19–9. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33(5):1032–1033. Epub 2017/10/19. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2017.028. PubMed PMID: 29050465; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6129637.

Kenney CD, Hoeger YE, Yetasook AK, Linn JG, Denham EW, Carbray J, et al. Management of non-parasitic splenic cysts: does size really matter? J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(9):1658–1663. Epub 2014/05/29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2545-x. PubMed PMID: 24871081.

Akhan O, Dagoglu-Kartal MG, Ciftci T, Ozer C, Erbahceci A, Akinci D. Percutaneous treatment of non-parasitic splenic cysts: long-term results for single- versus multiple-session treatment. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017;40(9):1421–1430. Epub 2017/05/01. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-017-1650-0. PubMed PMID: 28462445.

Rotas M, Ossowski R, Lutchman G, Levgur M. Pregnancy complicated with a giant splenic cyst: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007;275(4):301–305. Epub 2006/08/26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-006-0229-9. PubMed PMID: 16937120.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yoshiki Kajiwara, Eiji Shinto, Satsuki Mochizuki, Shuichi Hiraki, Yoshihisa Yaguchi, Hironori Tsujimoto, and Kazuo Hase for helpful advice regarding data collecting and assists in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no financial support.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YI collected the data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. TE and MF performed the operation and collected the data. KK, HN, MH and MN contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data. AK, TN and SA were involved in preoperative and postoperative evaluation of the patient. HU and JY made a preoperative diagnosis and reviewed the final manuscript. AM and HS performed the pathological diagnosis and interpreted the data. All of the authors contributed to drafting and critically revising the paper and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case report and the accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Imoto, Y., Einama, T., Fukumura, M. et al. Laparoscopic fenestration for a large ruptured splenic cyst combined with an elevated serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 level: a case report. BMC Surg 19, 58 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0517-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0517-5