Abstract

Background

In Korea, where gastric cancer is highly prevalent, biennial endoscopy is recommended among individuals over 40. Even under regular screening, some are still diagnosed at advanced stages. We aimed to identify characteristics of interval gastric neoplasms (IGNs) with rapid progression.

Results

Newly-diagnosed gastric neoplasms detected in screening endoscopy between January 2004 and May 2016 were reviewed. Among them, those who had previous endoscopy within 2 years were enrolled. Endoscopic findings, family history of gastric cancer, smoking, and H. pylori status were analysed. Totally, 297 IGN cases were enrolled. Among them, 246 were endoscopically treatable IGN (ET-IGN) and 51 were endoscopically untreatable IGNs (EUT-IGN) by the expanded criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Among EUT-IGNs, 78% were undifferentiated cancers (40/51) and 33% showed submucosal invasion (13/40). They were median 2.0 cm in size and more commonly located in the proximal stomach than ET-IGNs (70.6% vs. 41.9%, p < 0.001). EUT-IGN was independently related with age < 60 (OR, 2.09; 95%CI, 1.03–4.26, p = 0.042), H. pylori (OR, 2.81; 95%CI, 1.20–6.63, p = 0.018), and absent/mild gastric atrophy (OR, 2.67; 95%CI, 1.25–5.72, p = 0.011). Overall and disease-specific survival were not significantly different between the two groups, however EUT-IGN tended to have short disease-specific survival (overall survival, p = 0.143; disease-specific survival, p = 0.083).

Conclusions

Uniform screening endoscopy with two-year interval seems not enough for rapid-growing gastric neoplasms, such as undifferentiated cancers. They tended to develop in adults younger than 60 with H. pylori infection without severe gastric atrophy. More meticulous screening, especially for proximal lesions is warranted for adults younger than 60 with H. pylori infection before development of gastric atrophy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although its incidence and mortality are continuously decreasing, gastric cancer is still the 5th most common cancer and the 3rd leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Annually, more than a million new gastric cancer cases arise and more than 780,000 gastric cancer-related deaths occur over the world [1]. Especially in East Asia, gastric cancer is one of the greatest concerns due to the extremely high incidence [2,3,4]. In Korea, although the incidence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, which is one of the greatest risk factors for gastric cancer, has been gradually decreased, showing 66.9% in 1998, 59.6% in 2005, 54.4% in 2011, and 43.9% in 2016 [5], gastric cancer is still the most common cancer and its age-standardised rate reached up to 33.3 in 2017 statistics [6]. The National Cancer Screening Program in Korea, which covers biennial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for those over 40 years old, has been in place since 2004 [7, 8]. Since then, the five-year survival rate of gastric cancer in Korea has considerably increased, which although is still an unsatisfactory rate at less than 80% [9]. This can be attributed in part to insufficient endoscopic screening rate of only about 60% [10]. However, even despite regular screening, some are still diagnosed with advanced diseases.

Interval cancer is defined as cancer detected between regular screenings, which can be a great setback to the cancer screening. The concept of “interval cancer” is well established in colorectal cancer, as a quality indicator of screening [11]. However, little has been investigated about interval gastric cancer. This terminology of “interval gastric cancer” is occasionally used only in Far East where nationwide endoscopic screening for gastric cancer is established [12]. Interval cancer can be missed lesion or true new lesion. Qualified endoscopy may reduce missing rate, however, new lesions with rapid progression are inevitable. Also, whether the two-year interval of gastric cancer screening is optimal is still on debate. Several studies have reported better outcome of endoscopic screening with less than 2 years of interval [13,14,15]. In current study, we defined “interval gastric neoplasm (IGN)” as gastric neoplasm including dysplasia and cancer detected within 2 years after negative screening. We assumed that better understanding on IGN will enable better tailored-screening for gastric cancer. This study aimed to identify characteristics of IGN detected during regular screening and risk factors for rapid progression.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients who were newly diagnosed with gastric neoplasms, including dysplasia and cancer, during screening endoscopy at a single health-checkup center between January 2004 and May 2016. Among them, those who underwent previous endoscopy within 2 years were enrolled. Endoscopy was performed with Fujinon VP-XL 402/4400 until 2009 and Olympus CV-260SL/290 thereafter. In order to identify potential risk factors for rapid progression, we reviewed the following data: endoscopic findings, family history of gastric cancer within 1st degree relatives, smoking history (never vs. former/current), and H. pylori infection status. Those with either anti-H. pylori IgG antibody sero-positivity, positive result in rapid urease test, or histologic findings of H. pylori in Giemsa staining were considered to have H. pylori infection. Anti-H. pylori antibody was tested with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (H. pylori-EIA-Well, Radim, Rome, Italy) until March 2013 and with chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Immulite 2000 CMIA, Siemens, UK) since April 2013. Anti-H. pylori IgG levels higher than 30 U/mL by EIA and 1.10 IU/mL by CIMA were regarded positive. We also reviewed the previous endoscopic images to check if any abnormality had been found at the same location where the neoplasm developed. The Institutional Review Board of our center, which complies with the declaration of Helsinki, approved this study (IRB No. H-1504-045-663). Patient consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Definitions

In this study, endoscopically treatable-IGN (ET-IGN) was defined as adenoma or gastric cancer detected within 2 years after negative screening endoscopy, which is within the expanded criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), except for undifferentiated histology [16]. This includes low- to high-grade dysplasia regardless of size of the lesion or well- to moderately-differentiated adenocarcinoma. As for adenocarcinoma, following three size criteria were included: mucosal cancer without ulceration regardless of size, mucosal cancer < 3 cm with ulceration, or submucosal cancer < 3 cm with SM1 invasion.

Endoscopically untreatable-IGN (EUT-IGN) was defined as gastric cancer detected within 2 years after negative screening endoscopy, which is over the expanded criteria for ESD, including undifferentiated histology regardless of size.

Severity of gastric atrophy was defined using the Kimura-Takemoto classification designed for the categorisation of endoscopic atrophic gastritis [17] by three expert endoscopists (JHL, JHS, SJC) under mutual discussion. Intestinal metaplasia was defined as gross endoscopic finding with ash-colored mucosal nodularity.

Biopsy specimens were examined and reported according to the WHO criteria [18]. As for gastric cancer, well-to-moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma was classified as differentiated type, while poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma (poorly cohesive carcinoma), or mucinous carcinoma was classified as undifferentiated type.

Statistical analysis

For categorical variables, Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was applied, while Student t-test was used to compare continuous variables. Multivariable analysis was performed by using logistic regression analysis with potential risk factors found in univariable analyses with clinical relevance. Survival analysis was performed with log-rank test and Cox proportional hazard model. All the analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 23.0 for Windows (SPSS, Seoul, Korea). All tests were two-sided and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

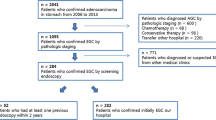

Overall, 625 patients who were newly diagnosed with gastric neoplasms were reviewed (Fig. 1). Among them, 300 patients who underwent previous upper gastrointestinal endoscopy within 24 months were included. One patient who had previous gastrectomy for peptic ulcer and two patients with unclear final pathology were excluded, and the remaining 297 individuals were finally enrolled. Among the total 297 lesions in 297 individuals, 149 were diagnosed with low-grade dysplasia, 22 with high-grade dysplasia, 124 with early gastric cancer (EGC), and 2 with advanced gastric cancer (AGC). Altogether, 246 cases were ET-IGNs and 51 cases were EUT-IGNs. There has been no one with synchronous lesions in this study.

Overall mean age was 59.4 and the EUT-IGN group was younger than the ET-IGN group (55.0 ± 8.5 vs 60.3 ± 9.0, p < 0.001, Table 1). Between the two groups, the EUT-IGN group had less proportion of males (58.8% vs 79.7%, p = 0.001) and smaller body mass index (BMI) at diagnosis than the ET-IGN group. Past history of cancer other than gastric cancer was not significantly different between the two groups. Overall family history of gastric cancer was found in 22.6% and it was not different between the two groups. Overall H. pylori infection rate was 71.6% and which was higher in EUT-IGN group, although without statistical significance (82.4% vs. 69.4%, p = 0.062). Smoking rate was significantly higher in the ET-IGN group (69.5% vs 49.0%, p = 0.005). The H. pylori infection rate among IGNs were higher than that among the general Korean population (59.6% in 2005; 54.4% in 2011; 43.9% in 2016) [5]. However, despite the decreasing general trend of H. pylori infection rate, the rate among IGN rather somewhat increased although without statistical significance (69.6% in 2004–2008; 68.2% in 2009–2013; 78.3% in 2014–2016; p = 0.231). Among the total 297 patients, about 10% (n = 31) had abnormal lesion at the same location in the previous endoscopy, however, the biopsies all revealed negative result for neoplasm, only with the finding of active gastritis. However, the rate of previous abnormal lesion at the same location was not different between the two groups (13.7 and 9.8% in the EUT-IGN and the ET-IGN groups, respectively, p = 0.399). Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia were significantly more common in the ET-IGN group than in the EUT-IGN group. Also, moderate to severe atrophic gastritis was more frequent in the ET-IGN group (81.7% vs 49.1%, p = 0.002).

Pathological characteristics of interval neoplasms

Table 2 shows the pathological characteristics of 297 IGNs. Overall median size was less than 1.0 cm, while the median size of EUT-IGNs was as large as 2.0 cm. Ulceration was ten times more commonly found in the EUT-IGN group than in the ET-IGN group (31.4% vs 3.3%, p < 0.001). Undifferentiated histology accounted for 80% of the EUT-IGNs, and submucosal invasion was detected in about one-third of the EUT-IGNs (13/40, 32.5%). ET-IGNs were most commonly found in the lower third of the stomach and then in the middle and upper third, whereas EUT-IGNs were commonly found in the order of the upper, middle, and lower third.

In this study, there were two cases of AGC (Table 3). Both were female nonsmokers with undifferentiated histology and both lesions were located in the upper third of the stomach. One had a 15.5 cm-sized lesion, with linitis plastica. In retrospective review, similar fold thickening was found at the same location of the previous endoscopic images, which was found to be overlooked at that time after a negative result using forceps-biopsy. The other case was detected with only 1.5 cm-sized ulcero-fungating lesion with non-specific findings from the previous endoscopy. Diffuse peritoneal seeding was found at the time of staging workup and this patient died after 14.8 months later.

Multivariable analysis for risk of EUT-IGN

We performed multivariable analysis to evaluate the risk for EUT-IGN with potentially associated variables which showed p values < 0.10 in the univariable analyses (Fig. 2). In this analysis, age < 60 [odds ratio (OR), 2.09; 95% CI, 1.03–4.26; p = 0.042], H. pylori infection (OR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.20–6.63; p = 0.018), and absent/mild atrophy (OR, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.25–5.71; p = 0.011) showed independent association with EUT-IGN under adjustment. Meanwhile, female sex (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 0.56–4.33; p = 0.397), BMI (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.84–1.05; p = 0.272), and smoking (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.25–1.72; p = 0.398) were not independently related with EUT-IGN.

Survival analysis of the IGNs

During the median follow-up duration of 58.4 months (interquartile range, 30.3–94.5), eight cases of death occurred in the ET-IGN group and four in the EUT-IGN group. Among them, two in each group were gastric cancer-related deaths. The detailed profiles of the two gastric cancer-related deaths developed among ET-IGN group are described in Table 4. Overall survival showed a tendency of lower survival in the EUT-IGN group than ET-IGN group, however, this failed to show statistical significance (p = 0.143, Fig. 3a). Under Cox proportional hazard model, EUT-IGN showed HR of 2.34 with 95% CI between 0.72 and 7.94, compared with ET-IGN. Meanwhile, gastric cancer-specific survival also showed a tendency of lower rate in EUT-IGN than in ET-IGN, with relatively near significance (p = 0.083, Fig. 3b). Under Cox proportional hazard model, EUT-IGN showed HR of 4.804 with 95% CI between 0.68 and 34.14.

Subgroup analysis among interval gastric cancers (IGCs)

We also performed subgroup analysis among IGCs excluding gastric dysplasia. Among them, endoscopically untreatable–IGCs (EUT-IGCs) were younger with larger composition of females, and less likely smokers (Supplementary Table 1). Also EUT-IGCs were less likely to have moderate-to-severe atrophy or intestinal metaplasia compared with endoscopically treatable-IGCs (ET-IGCs). Obviously, EUT-IGCs were more likely to have ulcers and larger lesions with submucosal invasion.

In multivariable analysis, age (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89–0.99; p = 0.01), female gender (OR, 4.00; 95% CI, 1.43–11.14; p = 0.01), and absent/mild atrophy (OR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.08–8.07; p = 0.03) were shown to be independently associated with EUT-IGC. Although without statistical significance, those with abnormalities found at the same location in the previous exam were shown to have high tendency to develop EUT-IGC (OR, 4.29; 95% CI, 0.86–21.26; p = 0.08).

In terms of survival, EUT-IGCs were more likely to have poorer overall survival and gastric cancer-specific survival, although without statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 1A and 1B).

Subgroup analysis among IGNs detected since 2010

As the scope used in the screening has been improved over time, the endoscopic images taken before 2010 were of poor quality with low resolution compared with those taken thereafter with new Olympus scope. Therefore, we performed subgroup analysis among IGNs detected since 2010. Since 2010, 204 IGNs were detected including 170 ET-IGN and 34 EUT-IGN. Their baseline and pathologic characteristics were not much different from those of overall subjects (Supplementary Table 2). In multivariable analysis, age < 60 (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.90–0.99; p = 0.02), H. pylori infection (OR, 3.92; 95% CI, 1.23–12.46; p = 0.02), and absent/mild atrophy (OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 1.25–8.72; p = 0.02) were revealed as independent risk factors for EUT-IGN, just like in the overall subjects.

Discussion

Overall, among the 297 patients with IGNs diagnosed by screening endoscopy, 17% had EUT-IGN and most of them were undifferentiated adenocarcinoma. After multivariable analysis, age < 60, H. pylori infection, and absent/mild atrophic gastritis were shown to be associated with EUT-IGN among health screening population. Also, patients with EUT-IGN showed a tendency of lower gastric cancer-specific survival compared with those with ET-IGN.

In this study, IGN was defined as gastric dysplasia or cancer diagnosed between biennial endoscopic screenings. As the concept of interval cancer is not widely used for gastric cancer, there have been little references regarding this. Several previous studies dealt with interval gastric cancer [19, 20], however our study is somewhat different from those studies. Usually, the concept interval cancer is used for quality indicator of screening. This means that it is highly probable that interval cancer is a missed lesion in the previous screening. However, interval cancer might be a newly developed lesion after a negative screening, as well. Unlike previous studies, we focused on the latter possibility, as we all reviewed previous endoscopic images and confirmed no abnormal findings. Also, considering the highly improved 5-year survival rate of gastric cancer, we need to more focus on the quality of life rather than mortality now-a-days. Whether to treat with surgery or endoscopic resection is one of the great component deciding the quality of life. Therefore, we also included dysplasia to further investigate the adequacy of 2 year interval and risk for rapid progression which disables endoscopic resection. In this concept the new definition of “IGN” was made.

It is well known that gastric cancer prognosis highly depends on the stage at diagnosis [21]. Also, it is widely accepted that EGC which is defined as gastric cancer confined to mucosa has very low rate of lymph node invasion [22] and is related with excellent 5-year survival rate compared with AGC [23]. Therefore gastric cancer is often divided into EGC and AGC considering its different treatment modality and prognosis. Also, gastric dysplasia has been widely accepted as precancerous lesion, since Correa et al. hypothesised the gastric carcinogenesis cascade which includes the serial progression of chronic inflammation into atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, gastric dysplasia, and finally gastric adenocarcinoma [24]. Therefore, we further divided IGN into ET-IGN and EUT-IGN according to the expanded criteria for ESD. Since ESD was first introduced in the 1990s, it has largely replaced the role of radical gastrectomy for EGC without lymph node metastasis. These days, ESD is established as one of the standard treatment modalities for early gastric neoplasm because it enables en bloc resection with less invasiveness than conventional surgery [25,26,27]. The quality of life in gastric cancer patients largely depends on whether endoscopic treatment is possible or not. With the prevalence of endoscopic screening, the proportion of early-stage diagnosis of gastric neoplasm increases, and thus the role of endoscopic treatment such as ESD is continuously growing as well. With the development of diagnostic and therapeutic technology, the EGC diagnosis rate nowadays reaches up to 80% in countries with high incidence rates of gastric cancer like Korea and Japan [14, 28]. Thus we further sub-classified gastric neoplasms according to the criteria for ESD to better reflect the prognosis and quality of life in patients with IGNs.

In this study, the clinicopathological characteristics of IGNs were not different from those of general gastric cancers in terms of mean age, male predominance, and the rate of H. pylori infection [1]. Meanwhile, patients with EUT-IGNs showed a significant difference; they were younger, with relatively higher proportion of female, with lower smoking rate. They had lower grade of atrophic gastritis and less likely to have intestinal metaplasia, despite higher rate of H. pylori infection and which are similar with the characteristics seen in diffuse type gastric cancer. Diffuse type gastric cancer is also related with younger age, rapid progression [29], and higher rate of H. pylori infection [30]. On the other hand, intestinal type GC is known to be more associated with multi-step carcinogenic cascade of chronic inflammation which comprises atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia [24, 31, 32]. In our study, among the EUT-IGNs, 80% were undifferentiated gastric cancers with Lauren diffuse type. As for the tumor location, EUT-IGNs showed tendency to be located at the upper or middle third of the stomach, while ET-IGNs were most commonly found at the lower third. This was also in line with the results of previous research which compared diffuse and intestinal type EGCs [30]. The relationship between H. pylori infection and the upper third gastric cancer has been controversial. However, a previous meta-analysis on this issue has shown that the relationship between cardia cancer and H. pylori infection is highly positive in Eastern countries where gastric cancer incidence is high, while it tends to be neutral or even negative in Western countries with low gastric cancer prevalence [33]. This phenomenon might be attributed to the co-existence of two distinct types of cancers, one similar to H. pylori-related gastric cancer and the other similar to acid/bile-related esophageal cancer, which are prevalent in Eastern and Western countries, respectively. Since the upper part of the stomach is usually observed less thoroughly than the antrum, there might have been missed lesions during the previous endoscopic examination. However, on the review of the previous endoscopic images, any abnormalities at the same location were all confirmed to be free of neoplastic change. Only one case with diffuse fold thickening in the previous exam, which showed negative result from the forcep biopsy was finally diagnosed as AGC with linitis plastica by using CT scan after the next screening endoscopy. This case gives a lesson that conscious evaluation is needed for cases suspicious for Bormann type IV AGCs. The two cases of interval AGCs in this study both survived less than 2 years since the diagnosis. The other one than the case of Bormann type IV gastric cancer was diagnosed with relatively small lesion, however revealed peritoneal seeding and was unable to undergo curative treatment. These cases show that regular biennial endoscopy cannot be the perfect screening for gastric cancer in a high prevalence area and customised screening or effective way of prevention is needed for high risk individuals.

In multivariable analysis, age < 60, H. pylori infection and absent/mild atrophic gastritis were demonstrated to be independent risk factors for EUT-IGN. Also, young age, female gender, and absent/mild atrophic gastritis were shown to be related with EUT-IGC in subgroup analysis among IGCs. Such factors are all known risk factors for the diffuse type gastric cancers [29, 30]. This means that endoscopic screening with two-year interval may not be enough for rapidly growing types of gastric cancers including those with undifferentiated histology. In current study, we did not count undifferentiated gastric cancers as the expanded criteria for ESD. Some researchers consider undifferentiated gastric cancers < 2 cm as a possible candidate for ESD [22, 23], however there are still controversy on this issue due to the possibility of lymph node metastasis [34, 35]. In this study, undifferentiated cancers were all included in the EUT-IGN group regardless of size. Two-thirds of undifferentiated cancers were larger than 2 cm, showing the rapid progression of undifferentiated cancers. Recent studies have reported that the long-term outcome of ESD was not different from that of surgery among undifferentiated gastric cancers < 2 cm [36, 37]. Taking this into account, under the assumption that undifferentiated cancers < 2 cm can be established as candidate for ESD, more intensive screening endoscopy less than two-year interval would be helpful for a high-risk group of undifferentiated gastric cancer. There have been several studies suggesting endoscopic screening with less than 2 years of interval [13,14,15]. We suppose our current result is in line with these studies in that it showed insufficiency of uniform biennial screening for early detection of gastric neoplasms.

Another solution for prevention of IGN, which is more likely to be acceptable in clinical practice would be extensive H. pylori eradication in adults, especially those younger than 60 years old. In our results, EUT-GN showed a tendency of lower disease-specific survival and included AGC cases. In general, gastric cancers in young ages are more likely to be aggressive and diagnosed at advanced stages. Therefore, H. pylori eradication for young adults regardless of the existence or severity of gastric atrophy might be helpful to reduce mortality from gastric cancer in a certain sub-population.

In this study, the median interval since last endoscopy was 12 months. This means that most of the enrolled subjects underwent endoscopy annually, showing that interval cancer can occur despite annual endoscopy. This is the reason why we designed this study. Some people develop gastric cancer very rapidly and even some skip the premalignant steps such as atrophy/intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia. Therefore, we performed subgroup analysis among only cancers excluding dysplasia, and where we found that IGC shows similar characteristics with IGN.

There are several limitations in this study. First, we did not compare the characteristics of EUT-IGN with healthy control, which made it unable to evaluate the general risk factors for EUT-IGN. However, healthy control is not considered indispensable since the risk factors for overall gastric cancer is already well-known. Second, we did not investigate gastrointestinal symptoms of the participants. The reason why these participants underwent screening within 2 years was not achieved. However, even though the recommended gastric cancer screening interval is 2 years by the National Cancer Screening Program in Korea, opportunistic screening is frequently performed with a shorter interval due to either the screenee’s preference or previously defined risk factors. Third, as our study included subjects over more than a decade of time, there were technical improvement in the endoscopic device. However, we could not adjust this factor.

Conclusions

Considering that one out of six IGNs were EUT-IGNs, current uniform screening with biennial endoscopy seems not enough to improve the prognosis of rapid growing neoplasms such as undifferentiated cancers. Also such rapid growing neoplasms tended to show relatively low disease specific survival. Therefore more meticulous and high-quality screening endoscopy which include close observation especially at proximal area with enough time should be applied for adults, especially those younger than 60 years old with H. pylori infection before the development of severe gastric atrophy.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IGN:

-

Interval gastric neoplasm

- H. pylori :

-

Helicobacter pylori

- ET-IGN:

-

Endoscopically treatable-IGN

- ESD:

-

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

- EUT-IGN:

-

Endoscopically untreatable-IGN

- EGC:

-

Early gastric cancer

- AGC:

-

Advanced gastric cancer

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- IGC:

-

Interval gastric cancer

- EUT-IGC:

-

Endoscopically untreatable-IGC

- ET-IGC:

-

Endoscopically treatable-IGC

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018:GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424.

Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Lee DH, Lee KH. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2017. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:306–12.

Yamamoto S. Stomach cancer incidence in the world. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:471.

Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S. The incidence and mortality of major cancers in China, 2012. Chin J Cancer. 2016;35:73.

Lim SH, Kim N, Kwon JW, Kim SE, Baik GH, Lee JY, et al. Trends in the seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and its putative eradication rate over 18 years in Korea: a cross-sectional nationwide multicenter study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204762.

Cancer type occurrence status. National Cancer Information Center website. Updated December 30, 2019. https://www.cancer.go.kr/lay1/S1T639C641/contents.do. Accessed 10 Apr 10 2020.

National cancer control programs in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22 Suppl:S3–4.

Park HA, Nam SY, Lee SK, Kim SG, Shim KN, Park SM, et al. The Korean guideline for gastric cancer screening. J Korean Med Assoc. 2015;58:373–84.

Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2016. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:417–30.

Suh M, Choi KS, Park B, Lee YY, Jun JK, Lee DH, et al. Trends in Cancer screening rates among Korean men and women: results of the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey, 2004-2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48:1–10.

Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795–803.

Kim B-W. Lessons from interval gastric cancer: read between the lines. Gut Liver. 2015;9:133–4.

Chung SJ, Park MJ, Kang SJ, Kang HY, Chung GE, Kim SG, et al. Effect of annual endoscopic screening on clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment modality of gastric cancer in a high-incidence region of Korea. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2376–84.

Nam SY, Choi IJ, Park KW, Kim CG, Lee JY, Kook MC, et al. Effect of repeated endoscopic screening on the incidence and treatment of gastric cancer in health screenees. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:855–60.

Yoon H, Kim N, Lee HS, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, et al. Effect of endoscopic screening at 1-year intervals on the clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment of gastric cancer in South Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:928–34.

Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4490–8.

Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;1:87–97.

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182–8.

Raftopoulos SC, Segarajasingam DS, Burke V, Ee HC, Yusoff IF. A cohort study of missed and new cancers after esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1292–7.

Park MS, Yoon JY, Chung HS, Lee H, Park JC, Shin SK, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of interval gastric Cancer in Korea. Gut Liver. 2015;9:166–73.

Park SR, Kim MJ, Ryu KW, Lee JH, Lee JS, Nam BH, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative clinical staging assessed by computed tomography in resectable gastric cancer patients: a viewpoint in the era of preoperative treatment. Ann Surg. 2010;251:428–35.

Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–25.

Hamashima C, Shabana M, Okada K, Okamoto M, Osaki Y. Mortality reduction form gastric cancer by endoscopic and radiographic screening. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:1744–9.

Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process-fist American Cancer Society award lecture on Cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6723–40.

Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: technical feasibility, operation time and complications from a large consecutive series. Dig Endosc. 2005;17:54–8.

Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331–6.

Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim SJ, Cho JY, Cho WY, et al. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD study group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1228–35.

Hosokawa O, Miyanaga T, Kaizaki Y, Hattori M, Dohden K, Ohta K, et al. Decreased death from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening: association with a population-based cancer registry. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1112–5.

Kunz PL, Gubens M, Fisher GA, Ford JM, Lichtensztajn DY, Clarke CA. Long-term survivors of gastric cancer: a California population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3507–15.

Lee JY, Gong EJ, Chung EJ, Park HW, Bae SE, Kim EH, et al. The characteristics and prognosis of diffuse-type early gastric Cancer diagnosed during health check-ups. Gut Liver. 2017;11:807–12.

Whiting JL, Sigurdsson A, Rowlands DC, Hallissey MT, Fielding JW. The long term results of endoscopic surveillance of premalignant gastric lesions. Gut. 2002;50:378–81.

de Vries AC. Can Grieken NC, Looman CW, Casparie MK, de Vries E, Meijer G, et al. gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:945–52.

Cavaleiro-Pinto PB, Lunet N, Barros H. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cardia cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:375–87.

Hirasawa T, Gotoda T, Miyata S, Kato Y, Shimoda T, Taniguchi H, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:148–52.

Oh SY, Lee KG, Suh YS, Kim MA, Kong SH, Lee HJ, et al. Lymph node metastasis in mucosal gastric cancer. Reappraisal of expanded indication of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Ann Surg. 2017;265:137–42.

Lim JH, Kim J, Kim SG, Chung HS. Long-term clinical outcomes of endoscopic vs. surgical resection for early gastric cancer with undifferentiated histology. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:3589–99.

Lee S, Choi KD, Han M, Na HK, Ahn JY, Jung KW, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery in early gastric cancer meeting expanded indication including undifferentiated-type tumors: a criteria-based analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:490–9.

Acknowledgements

The statistical review of this study was performed by Gu-Cheol Jung, the biomedical statistician of Healthcare Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital Healthcare System Gangnam Center. This study was presented at the UEG Week 2019 Oral Presentations (OP369), which you can find in following website:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/2050640619854670.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by JHL, JHS, and SJC. Data collection and analysis were performed by JHL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JHL. Critical revision was performed by GEC and JSK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1996 and later versions. The Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital, which complies with the declaration of Helsinki, approved this study (IRB No. H-1504-045-663). Formal consent was not obtained because of the retrospective nature or this study, and which was approved by the Institutional Review Board. No personal identification information is included in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1 Fig. S1

Kaplan-Meier curves comparing ET-IGC and EUT-IGC: (a) Overall survival; (b) Gastric cancer-specific survival. ET-IGC, endoscopically treatable-gastric cancer; EUT-IGC, endoscopically untreatable-gastric cancer.

Additional file 2 Table S1

. Baseline and pathologic characteristics of interval gastric cancer. Table S2. Baseline and pathologic characteristics of interval gastric neoplasms detected since 2010.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, J.H., Song, J.H., Chung, S.J. et al. Characteristics of interval gastric neoplasms detected within two years after negative screening endoscopy among Koreans. BMC Cancer 21, 218 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07929-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07929-y