Abstract

Background

Institutional delivery is the cornerstone reducing maternal mortality. Community-based behavioral change interventions are increasing institutional delivery in developing countries. Yet, there is a dearth of information on the effect of attending pregnant women’s conferences in improving institutional delivery in Ethiopian. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess the effect of attending pregnant women’s conference on institutional delivery, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Community-based comparative cross-sectional study was conducted in 2017 among 871 women who gave birth within the last 12 months (435: pregnant women’s conference attendants and 436: pregnant women’s conference non-attendants). Participants were selected by using a multistage-simple random sampling technique and a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. Both descriptive and logistic regression analyses were performed using SPSS V.23. A P-value less than or equal to 0.05 at 95% confidence interval was set to test statistical significance.

Results

Institutional delivery among women who attended pregnant women’s conferences was 54.3%, higher compared with 39.9% of women who didn’t attend the conference. Likewise, the level of well-preparedness for birth was higher among women who attended the conference (38.9%) compared with their counterparts (25.7%). Being knowledgeable on childbirth (AOR = 1.7, 95%CI: 1.2, 2.8) and postpartum danger signs (AOR = 14.0, 95%CI: 4.6, 40.0), and discussed with partners/families about the place of birth (AOR = 7.7, 95%CI: 3.6, 16.4) were more likely to institutional delivery among women who attended pregnant women’s conference. Whereas, among women who didn’t attend the pregnant women’s conference, being knowledgeable about pregnancy danger signs (AOR = 3.6, 95%CI: 1.6, 8.1) were more likely to institutional delivery. In addition, the nearest health facility within 1 h of walking and well-preparedness for birth and its complication were found positively associated with institutional delivery in both groups.

Conclusion

Institutional delivery was low in both groups compared to the national plan, but was higher among women who attended the conference. Similarly, women’s knowledge of obstetric danger signs and preparation for birth and its complication was higher among women who attended the conference. Therefore, encouraging women to attend the pregnant women’s conference and discuss with their families about the place of delivery should be strengthened.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, maternal mortality had reduced by 44% in the time between 1990 and 2015. More than 35 women died worldwide every hour due to the complications of pregnancy and childbirth in 2015, of which, Sub-Saharan Africa alone accounts for almost two-thirds (66%) of global maternal death [1, 2]. In Ethiopia maternal death is the highest in the world which accounts, 412 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2016 [3]. Sustainable development goal has planned to reduce the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 216 to 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 [4].

Institutional delivery is the cornerstone reducing maternal Mortality. However, institutional delivery use is low [3, 4]. Behavioral changing community-based intervention is globally endorsed to reduce delays for care by increasing obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness knowledge [5, 6]. Developing countries have recently worked in behavior change and community mobilization interventions to increase institutional delivery [7,8,9].

The government of Ethiopia has strived to improve institutional delivery by introducing innovative practices like community participation, the adaptation of cultural practices at health facility level such as preparation of “maternal waiting home” at the health facility, making the service free of charge and provision of the ambulance for transportation of pregnant women during labor and delivery. Health developmental army and health extension workers having great changes in the utilization of maternal and childcare [10,11,12,13]. In addition to this, Ethiopian minister of health launched community-based intervention so-called “pregnant women’s conference” (PWC) to enhance obstetric danger sign awareness and institutional skilled maternal health service utilization. PWC is aimed to increase institutional delivery, by reducing delay in deciding to seek care and in the process of seeking care through enhancing the knowledge of obstetric danger signs and encourage proactive preparation toward childbirth and against the occurrence of any complication ahead of time among pregnant women. Every pregnant woman expected to attend at least three times during each pregnancy. It is given by Nurse/Midwives monthly at their kebele level/the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia/ and coordinated by health extension workers. There are studies in Ethiopia about institutional delivery but evidence on the effect of PWC on institutional delivery is scant. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess the effect of attending a pregnant women’s conference on institutional delivery by comparing women who attended the conference and women who didn’t attend the conference during their last pregnancy in rural Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study area and period

The study was conducted in rural Libo Kemkem District Northwest Ethiopia from February 15 to March 26, 2017. Libo Kemkem District is found 645 km away from Addis Ababa’s capital city of Ethiopia. The district has 29 rural Kebeles & 5 urban Kebeles with a total population, 261, 170 in 2016/17 according to the population projection made from the 2007 Ethiopian population and housing census, of which, the rural population accounts 223,378 people [14].

Study design

Community-based comparative cross-sectional study design was conducted among women who gave birth within the last 12 months.

Sample size

The minimum sample size for each group was calculated using the formula of two-sample comparisons of proportion by using Epi-Info V.7 StatCalc, cohort or cross-sectional, based on the following assumptions: confidence level 95%, power 80, and the proportion of institutional delivery among intervention and controlled group from the Burkina Faso study was 56 and 36% respectively, as there is no similar study conducted in the country to be used as a base to determine the sample size [15]. Adding of 5% non-response rate and multiplied by 2 (design effect because to be used multistage sampling method), the final minimum sample size calculated for each group was 450.

Study population and sampling technique

In this study, a multistage-simple random sampling technique was employed to recruit 450 women who gave birth in the last 12 months for each group. Of the total rural Kebeles found in the district, seven Kebeles were selected using a simple random sampling method. Then the study participants grouped into PWC attendants and PWC non-attendants by reviewing their family matrix book found from each kebele’s health post based on pregnant women’s conference attending history. Women who didn’t attend the PWC during their last pregnancy considered as the PWC non-attendants and women who attended the PWC during their last pregnancy considered as the PWC attendants. The calculated sample size was, then, proportionally allocated to each Kebele’s and group’s based on the number delivery in the last 12 months. Next, a simple random sampling technique was applied to select the study participants for each group.

Data collection

A pre-tested structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. The tool was prepared in English and translated to the local language, Amharic. Three female diploma midwives and one bachelor degree holder nurse were deployed as data collectors and supervisors respectively after receiving a one-day intensive training.

Operational definition

Well-prepared

A mother was considered as “well-prepared” if she made at least three from the four key types of birth preparedness and complication readiness practice during her last pregnancy (identified the skilled provider, saved money, planned health facility for delivery and identified the mode of transportation) before the onset of labor.

Knowledgeable on danger signs during pregnancy

A mother was considered as knowledgeable on danger signs during pregnancy if she spontaneously mentioned two or more of the three key danger signs these may occur during pregnancy (severe vaginal bleeding, swollen hands/face, and blurred vision).

Knowledgeable on danger signs during birth

A mother was considered as knowledgeable on danger signs during birth if she spontaneously mentioned two or more of the four key danger signs these may occur during childbirth (severe vaginal bleeding, prolonged labor (> 12 h), convulsion and placenta retained).

Knowledgeable on danger sign during postpartum

A mother was considered as knowledgeable on danger signs during postpartum if she spontaneously mentioned two or more of the three key danger signs these may occur during the postpartum period (severe vaginal bleeding, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, and high fever).

Data analysis

The collected data were entered into Epi Info V.7 and exported to SPSS Version 23 for analysis. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were done. In the analytical study, the first bivariable logistic regression analysis used to identify the independent effect of each on institutional delivery for each group. Variables having P-value ≤0.20 in the bivariable analysis were remained in the multivariable analysis to control the effect of confounders. Before doing independent logistic regression analysis among women who attended the PWC and didn’t attend the PWC independently, a significant difference between two independent groups was done since the study was comparative. Chi-square testing was done to see if there was any significant on prevalence of institutional delivery among mothers who attended and didn’t attend the PWC and a statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups (x2 = 17.98, df = 1, p = < 0.001), indicating that the factors associated with institutional delivery could be different among women attended and didn’t attend the PWC. Therefore, the analysis was conducted separately. Odds ratios (AOR) with their 95% CI were calculated to measure the strength of association, and P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

Four hundred and fifty questionnaires were each distributed to both PWC attendant and PWC non-attendant respondents. However, 435 and 436 questionnaires were analyzed, yielding a response rate of 96.7 and 96.9%, respectively, women attended the PWC and didn’t attend the PWC. The mean age of women attended and didn’t attend the PWC was almost similar (30.9 ± 5.5 years VS 31.6 ± 5.1 years respectively). Almost all (93.1%) women were orthodox religion followers and the rest, 6.9% were Muslim religion followers. More than half (56.8%) of women who attended the PWC were living within 1 h of walking from the nearest health facility, whereas, 55% of women didn’t attend the PWC were living far away 1 h of walking. In both groups, the majority of women’s age group was 25-34 years (attended PMC: 75.8%, didn’t attend PMC: 60.9%) (Table 1).

Obstetric characteristics of respondents

The majority of women, 92.2% of women who attended the PWC and 78.0% of women who didn’t attend the PWC were had at least one ANC visit during their last pregnancy. About 1.4 and 3.4% of women who attended and didn’t attend the PWC had a history of stillbirth respectively (Table 2).

Awareness of obstetric danger signs

Almost all, 99.8% of women who attended the PWC and 95.4% of women who didn’t attend the PWC knew at least one key danger sign that may occur during pregnancy, childbirth or postpartum periods. Above three-fifth (61.8%) and two-fifth (40.4%) of women who attended and didn’t attend the PWC were mentioned sever vaginal bleeding as a danger sign during pregnancy, respectively (Table 3).

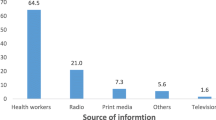

Knowledge of obstetric danger signs

The proportion of women with adequate knowledge about danger signs that may occur during pregnancy was 40.7 and 24.1% for both women who attended the PWC and didn’t attend PWC, respectively (Fig. 1).

Birth and its complication readiness practice during their last pregnancy

Almost three-fourth (73.3%) of women who attended the PWC and half (54.4%) of women who didn’t attend the PWC, reported that they were planned health facility for delivery before the onset of labor (Fig. 2).

Well-preparedness

Of the total, 38.9% of women who attended the PWC (95%CI: 33.8-43.7), and 25.7% of women who didn’t attend the PWC (95% CI: 22.2-29.4) were “well-prepared” for birth and its complication during their last pregnancy before the onset of labor (Fig. 3).

The planned place for delivery and reasons

Almost one-fourth (26.7%) of women who attended the PWC and a half (45.6%) of women didn’t attend the PWC were planned to give birth at a home. Women feel more comfortable giving birth at home and need close attention from their families or relatives were frequently mentioned reasons why they planned to give birth at home in both groups (Table 4).

Institutional delivery

The proportion of institutional delivery was 54.3% (p = 54.3, 95%CI: 49.9, 59.1) and 39.9% (p = 39.9, 95%CI: 35.3, 44.7%) among women who attended and didn’t attend the PWC, respectively. About 22.3% of women who attended the PWC and 13.5% of women who didn’t attend the PWC were had at least two PNC follow up during current delivery (Table 5).

Factors associated with institutional delivery

On bi-variable, knowledge of danger signs in pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period, traveling time to reach the nearest health facility, well prepared for birth and its complication, and discussion with partners/families about the place of birth were significantly associated with institutional delivery in both groups. On multivariable analysis, among women who attended the PWC, knowledge of danger signs that may occur during childbirth and the postpartum period, traveling time to reach the nearest health facility, well prepared for birth and its complication, and discussion with partners/families about the place of birth were significantly associated with institutional delivery. Whereas, among women who didn’t attend the PWC, knowledge of danger signs that may occur during pregnancy, traveling time to reach the nearest health facility and well prepared for birth and its complication were significantly associated with institutional delivery.

Among women who attended the PWC those who were knowledgeable on childbirth danger signs had 1.7 times higher odds of institutional delivery compared to women who were not knowledgeable on childbirth danger signs (AOR = 1.7, 95%CI: 1.2, 2.8). Whereas, the Odds of institutional delivery among women didn’t attend PWC those who had knowledge of pregnancy danger signs were 3.6 times higher compared with their counterparts (AOR = 3.6, 95%CI: 1.6, 8.1) (Table 6).

Discussion

According to this study, the proportion of institutional delivery among women who attended the PWC was 54.3%, higher compared with 39.9% among women who didn’t attend the PWC. Similarly, higher institutional delivery among women who involved in the community-based interventions was reported in the studies done in Burkina Faso (56% VS 36%), Eritrea (46.8% VS 51.2) and Guatemala (54.7% VS 31.2%) [15,16,17]. The reason might be, women who involved in the intervention expected that they were better informed about obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness, that enables women were better placed to make reasonable decisions [18]. Community-based behavioral changing interventions believed that increase institutional delivery, however, in the study done Kenya (28% VS 37%), Bangladesh (10.5% VS 12.5%), and India (22.5% VS 21.8%) institutional delivery among intervention groups similar or lower compared with not encompass in the interventions [19,20,21]. The reason might be a poor monitoring system of the interventions, and different socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

The level of institutional delivery in both groups lower compared to studies done in Arba Minch (73.2%), Debre-Berhan (80.2%), and Ghana (63.3%) [22,23,24]. However, it was higher compared with the studies done in Dangla District (18.3%), and Banja District (15.7%) [25, 26]. The reason might be due to differences in socio-economic, and demographic characteristics of participants. Women who are educated, single, urban residents, and higher socioeconomic status are able to make wise decisions about their own health than their counterparts [18, 27,28,29,30,31].

This finding revealed that the awareness of obstetric danger signs in pregnancy, labor, and postpartum was higher among women who attended the PWC compared to those women who didn’t attend the PWC. This finding was in line with the studies done in Eritrea, and Bangladesh [16, 20]. On the other hand, acquiring of obstetric danger signs knowledge was not always consistency with related interventions. The studies conducted in Nepal and Bangladesh showed that obstetric danger signs knowledge of women who involved in the intervention were similar or lower compared to women those not participating in the interventions [32, 33]. The level of well-preparedness for birth and its complication practice was also significantly higher among women who attended the PWC, accounting 38.9% compared with 27.5% among women who didn’t attend the PWC. Similarly, in the studies done in Burkina Faso, Eretria, Nepal, and Tanzania the higher level of well-preparedness for birth and its complication was made among women who participated in the interventions [8, 16, 34, 35]. The reason might be women who involved in the intervention were better informed about birth preparedness and its complications.

The odds of institutional delivery among PWC attendant women who had knowledge of childbirth and postpartum danger signs were higher compared to their counterparts. On the other hand, among PWC non-attendant women who had knowledge of pregnancy danger signs were more likely to institutional delivery compared to their counterparts. Similarly, obstetric danger signs knowledge was positively associated with institutional delivery in the previous study done in Ethiopia, Pakistan, and Tanzania [18, 36, 37]. The possible explanation might be having knowledge of obstetric danger signs may influence women’s perceptions about their susceptibility to and seriousness of the complications. This might motivate women to give birth at health facilities [31].

In both groups, women who well-prepared for birth and its complication were more likely to institutional delivery. The reason might be women who were well prepared for birth and its complication might be knowledgeable about obstetric complications that may occur before, during and after birth; positively influence to give birth at a health facility.

Traveling time from the nearest health facility was significantly associated with institutional delivery in both women who attended and didn’t attend the PWC. In both groups, women who lived within 1 h of walking from the nearest health facility were more likely to institutional delivery compared to their counterparts. This finding was in line with other previous studies [18, 27, 28, 31]. The reason might be a lack of means of transportation to health facilities. Secondly, fear of financial cost for transport might be negatively influenced to decide institutional delivery.

The odds of institutional delivery among PWC attendant women who had a discussion with partners/families about the place of birth were higher compared with women who didn’t discuss. This may enable women to have autonomy in the choice of birthplace jointly. Women with the highest level of autonomy most likely to seek institutional delivery [36, 38,39,40]. In addition, this might create a better opportunity for families to involve in arranging transport, save money, and help mothers to choice a place of delivery.

Conclusion

The proportion of institutional delivery was low in both groups compared to the national plan. However, it was higher among women who attended the conference. Similarly, women’s knowledge of obstetric danger signs and preparation for birth and its complication were higher among women who attended the conference compared with women who didn’t attend the conference. Pregnant women’s conference attendant women who had knowledge of childbirth and postpartum, and discussed with their partners/families about the place of delivery were more likely to institutional delivery. On the other hand, pregnant women’s conference non-attendant women who had knowledge about pregnancy danger signs were more likely to institutional delivery. In both groups, women who lived with one-hour of walking from the nearest health facility and well prepared for birth and its complication were more likely to institutional delivery. Therefore, strengthening women to attend pregnant women’s conference may improve institutional delivery by increasing women’s obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness knowledge. Furthermore, encouraging women to discuss with their families about the place of delivery should be strengthened. In addition, the government of Ethiopia better to strengthen the accessibility of health facilities for women.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to generate and or analyzed the current study are available from the corresponding author upon the request.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- PWC:

-

Pregnant women’s conference

References

Alkema L, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–74.

Bongaarts J, WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations. Population division trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. Popul Dev Rev. 2016;42(4):726–6.

Demographic IE. Health survey 2016: key indicators report. Addis Ababa and Rockville: CSA and ICF; 2016.

Assefa Y, et al. Successes and challenges of the millennium development goals in Ethiopia: lessons for the sustainable development goals. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(2):e000318.

Mbalinda SN, et al. Does knowledge of danger signs of pregnancy predict birth preparedness? A critique of the evidence from women admitted to pregnancy complications. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12(1):60.

Nawal D, Goli S. Birth preparedness and its effect on the place of delivery and post-natal check-ups in Nepal. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e60957.

Skinner J, Rathavy T. Design and evaluation of a community participatory, birth preparedness project in Cambodia. Midwifery. 2009;25(6):738–43.

Moran AC, et al. Birth-preparedness for maternal health: findings from Koupéla district, Burkina Faso. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24(4):489.

Mushi D, Mpembeni R, Jahn A. Effectiveness of community-based safe motherhood promoters in improving the utilization of obstetric care. The case of the Mtwara Rural District in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2010;10(1):14.

Medhanyie A, et al. The role of health extension workers in improving the utilization of maternal health services in rural areas in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):352.

Banteyerga H. Ethiopia’s health extension program: improving health through community involvement. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13(3):46–9.

FMoH. Health and Health-Related Indicators. Addis Ababa; 2011. http://www.moh.gov.et.

FMoH. HSDP IV. Annual Performance Report (2012/2013). Addis Ababa; 2013. http://www.moh.gov.et.

LiboKemkem District Health Office. Annual Report 2016/17. Amhara Region, Northwest, Ethiopia; 2017.

Brazier E, et al. Improving poor women's access to maternity care: findings from a primary care intervention in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(5):682–90.

Turan JM, Tesfagiorghis M, Polan ML. Evaluation of a community intervention for the promotion of safe motherhood in Eritrea. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2011;56(1):8–17.

Becker F, Yglesias C. Measuring the effects of behavior change and service deliver interventions in Guatemala with population-based survey. Maryland, USA: JHPIEGO; 2004. p. 20–9.

Mpembeni RN, et al. Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in Southern Tanzania: implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7(1):29.

Family Care International. Care –seeking during pregnancy, delivery and the postpartum period: A Study in Homabay and Migori Districts., Kenya: FCI; 2003. Available at SSRN 992253.

Hossain J, Ross S. The effect of addressing the demand for as well as a supply of emergency obstetric care in Dinajpur, Bangladesh. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006;92(3):320–8.

Baqui A, et al. Impact of an integrated nutrition and health program on neonatal mortality in rural northern India. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:796–804A.

Saaka M, Aviisah MA. Promoting skilled institutional deliveries: factors to consider in a free maternal health services policy environment. Med Res Chronicles. 2015;2(3):286–302.

Kelebore WG, Asefa A, Tunje A, Shibiru S, Hassen S, Getahun D, Mamo M. Assessment of factors affecting institutional delivery service utilization among mother who gave birth in last two years, Arbaminch town, Gamo Gofa zone, Snnpr, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2016;4(6):458.

Limenih A, Deyesa N, Berhane A. Assessing the magnitude of institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers in Debre Berhan, Ethiopia. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2016;3:254. https://doi.org/10.4172/2376-127X.1000254.

Demilew YM, Gebregergs GB, Negusie AA. Factors associated with institutional delivery in Dangila district, North West Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16(1):10–7.

Wolelie A, Aychiluhm M, Awoke W. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors in Banja District, Awie zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Open J Epidemiol. 2014;4(01):30.

Yanagisawa S, Oum S, Wakai S. Determinants of skilled birth attendance in rural Cambodia. Tropical Med Int Health. 2006;11(2):238–51.

Stekelenburg J, et al. Waiting too long: low use of maternal health services in Kalabo, Zambia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9(3):390–8.

Nwakoby BN. Use of obstetric services in rural Nigeria. J R Soc Health. 1994;114(3):132–6.

Osubor K, Fatusi AO, Chiwuzie J. Maternal health-seeking behavior and associated factors in a rural Nigerian community. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(2):159.

Alemi Kebede KH, Teklehaymanot AN. Factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization in Ethiopia. Int J Women’s Health. 2016;8:463.

Sood S, et al. Measuring the effects of behavior change interventions in Nepal with population-based survey results: JHPIEGO; 2004. http://www.jhpiego.org/.

Darmstadt GL, et al. Evaluation of a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a package of community-based maternal and newborn interventions in Mirzapur, Bangladesh. PloS One. 2010;5(3):e9696.

McPherson RA, et al. Are birth-preparedness programs effective? Results from a field trial in Siraha district, Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24(4):479.

August F, et al. Effectiveness of the Home Based Life Saving Skills training by community health workers on knowledge of danger signs, birth preparedness, complication readiness and facility delivery, among women in Rural Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):129.

Tura G, G/Mariam A. Safe delivery service utilization in Metekel zone, northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2008;18(1).

Agha S, Carton TW. Determinants of institutional delivery in rural Jhang, Pakistan. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):31.

Fikre AA, Demissie M. Prevalence of institutional delivery and associated factors in Dodota Woreda (district), Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2012;9(1):33.

Hagos S, et al. Utilization of institutional delivery service at Wukro and Butajera districts in Northern and South Central Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):178.

Asefa A, et al. Mismatch between antenatal care attendance and institutional delivery in South Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e024783.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude for the South Gondar Zone Health Office, Libo Kemkem, District Health Offices, study participants, data collectors, supervisor, Health extension workers, and Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Science for their contribution to do this work.

Funding

Nil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: MBA. Performed the study and analysis: MBA and GWD. Wrote the paper MBA and GWD. Manuscript preparation: MBA and GWD. Finally, both authors read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Both authors are a lecturer at the department of reproductive health and population studies, School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Bahir Dar University’s ethical review committee. Permission letter was taken from Amhara Regional Health Bureau, South Gondar Zonal and Libo Kemkem Health Offices. Written consent was obtained from each study subject and the purpose of the study explained to participants before the interviewed. Confidentiality was maintained by omitting their personal identifications such as names that were not recorded.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Asresie, M.B., Dagnew, G.W. Effect of attending pregnant women’s conference on institutional delivery, Northwest Ethiopia: comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 353 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2537-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2537-7