Abstract

Fatigue is a disabling, multifaceted symptom that is highly prevalent and stubbornly persistent. Although fatigue is a frequent complaint among patients with fibromyalgia, it has not received the same attention as pain. Reasons for this include lack of standardized nomenclature to communicate about fatigue, lack of evidence-based guidelines for fatigue assessment, and a deficiency in effective treatment strategies. Fatigue does not occur in isolation; rather, it is present concurrently in varying severity with other fibromyalgia symptoms such as chronic widespread pain, unrefreshing sleep, anxiety, depression, cognitive difficulties, and so on. Survey-based and preliminary mechanistic studies indicate that multiple symptoms feed into fatigue and it may be associated with a variety of physiological mechanisms. Therefore, fatigue assessment in clinical and research settings must consider this multi-dimensionality. While no clinical trial to date has specifically targeted fatigue, randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses indicate that treatment modalities studied in the context of other fibromyalgia symptoms could also improve fatigue. The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Fibromyalgia Working Group and the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) have been instrumental in propelling the study of fatigue in fibromyalgia to the forefront. The ongoing efforts by PROMIS to develop a brief fibromyalgia-specific fatigue measure for use in clinical and research settings will help define fatigue, allow for better assessment, and advance our understanding of fatigue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Fatigue in fibromyalgia: common problem, multiple causes

Fibromyalgia is a chronic, multi-symptom complex with no effective treatment. It affects 2% of the United States population and significantly impacts both healthcare costs and utilization of healthcare resources [1, 2]. In addition to unrefreshing sleep, cognitive difficulties and affective symptoms, chronic widespread pain and fatigue are its cardinal symptoms [3, 4]. For patients with fibromyalgia and their treating clinicians, fatigue is a complicated, multifactorial, and vexing symptom that is highly prevalent (76%) and stubbornly persistent, as evidenced by longitudinal studies over 5 years [5–7].

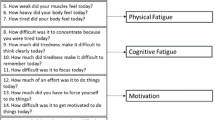

Despite its disabling effects, fatigue has not received the same research attention in fibromyalgia as has pain, for a variety of reasons. First, there is no established nomenclature with which to describe the multiple types and manifestations of fatigue. Patients with fibromyalgia may experience fatigue physically (lack of energy, physical exhaustion), emotionally (lack of motivation), cognitively (inability to think or concentrate), or via the symptom’s impact on virtually any aspect of living, such as the ability to work, meet family needs, or engage in social activities [8]. Patients may experience these different types of fatigue simultaneously, but clinicians rarely sort this through during the typical office visit, and the complaint is often chronicled simply as 'fatigue’. Second, clinical experience indicates that patients usually do not feel comfortable making an appointment for 'just’ fatigue. They need a medical condition or an acceptable symptom (as institutionally and culturally dictated), such as pain, despite the fact that fatigue is reported as a bothersome symptom in up to 80% of patients with chronic conditions and is a common complaint in both primary and specialty clinics [9–11]. Third, the lack of understanding of the mechanisms of fatigue contributes to poor assessment and treatment strategies, and may make providers wary of broaching the topic in a clinical encounter.

Fortunately, two recent initiatives, the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) [12–15] and the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) [16], are helping to move the study of fatigue in fibromyalgia forward. OMERACT organized focus groups and Delphi studies of both patients with fibromyalgia and physician experts that have resulted in important recommendations for assessment and treatment of fatigue. First among these was the ranking of fatigue, pain, sleep, quality of life, mood, and cognition as the most relevant symptoms in fibromyalgia, and second, the recommendation that fatigue be assessed in all clinical trials of fibromyalgia. PROMIS, an initiative of the National Institutes of Health, developed item response theory-based banks to assess symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and sleep, as well as quality of life measures. The goal of this initiative was to 1) create measures that are valid, reliable, and generalizable for clinical outcomes that are important to patients, 2) reliably assess patient response to interventions, and 3) inform treatment modifications. The PROMIS Fatigue Item Bank (PROMIS-FIB) contains 95 items that evaluate the spectrum of fatigue from mild subjective feelings of tiredness to an overwhelming, debilitating, and sustained sense of exhaustion that interferes with activities of daily living, family, and social roles [17]. The assessment categories are divided into the experience (frequency, duration, and intensity) and impact of fatigue on physical, mental, and social activities. Work is currently underway to assess the psychometric properties of the PROMIS-FIB and develop a brief fibromyalgia-specific measure for clinical and research purposes.

The objectives of this narrative review are to 1) provide a general overview of the current knowledge of fatigue in the context of fibromyalgia, 2) suggest a rationale for assessment of fatigue, and 3) describe non-pharmacological and pharmacological management modalities studied in the context of fibromyalgia that also improve fatigue. While this is not a systematic review, this critical narrative review may guide clinical decisions when faced with a fatigued patient with fibromyalgia.

Search strategy

The search was performed using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, and EBSCO CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature), covering 2000 through May 2013. The search strategy used controlled vocabulary (subject headings) and text words in the title and/or abstract - fibromyalgia, fatigue and synonyms related to fatigue (for example, weakness, tiredness, exhaustion, stiffness, depression). The results were limited to English, publication format (review, meeting abstract) and study designs (trials, cohort studies, systematic reviews), yielding a total of 644 unique publications.

Fatigue characteristics: qualitative research

Results of qualitative studies provide insights into the encumbrance that fatigue inflicts on patients with fibromyalgia and the concomitant problem of articulating to their doctors what is wrong. Patients with fibromyalgia describe fatigue as 'an inescapable or overwhelming feeling of profound physical tiredness’, 'weakness in the muscles’, 'an uncontrollable, unpredictable constant state of never being rested’, 'a ghastly sensation of being totally drained of every fiber of energy’, 'not proportional to effort exerted’, 'not relieved by rest’, 'having to do things more slowly’, and 'an invisible foe that creeps upon them unannounced and without warning’ [8, 18, 19]. Patients also report that fatigue is interwoven, influenced, and intensified by pain, and is sometimes more severe than pain [18]. Although fatigue is reported by both men and women with fibromyalgia, one study demonstrated that men had less fatigue compared to women and a second study reported that men tend to focus more on pain and women on fatigue [8, 20].

Fatigue correlates: insights into etiology

The key symptoms of fibromyalgia - pain, fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, dyscognition, and depressed mood - do not occur in isolation. Rather, they often present concurrently, in varying severity, and are intertwined with and influence each other (Figure 1). Indeed, studies demonstrate that chronic persistent pain (both from abnormal central sensitization and maintenance of nociceptive pain from peripheral pain generators), poor sleep quality (subjective report and objective measures), depressed mood, anxiety, or combinations of these are associated with fatigue [21–23] (Table 1). In addition to common fibromyalgia symptoms, clinical characteristics (for example, body mass index), health behaviors (for example, physical activity levels), and psychological variables (for example, negative affect, catastrophizing, affect regulation), also demonstrate strong associations with fatigue [22–27] (Table 1). In addition to cross-sectional associations, diurnal rhythmicity and lag relationships have also been demonstrated between fatigue and other fibromyalgia symptoms (particularly pain, stiffness, and affect), suggesting that one variable can influence or predict the others [28, 29]. Appreciating these associations is important in fatigue assessment because daily assessment of fatigue may uncover lag relationships with other symptoms, providing avenues for intervention. Collectively, these studies indicate that many symptoms feed into fatigue and the implication of this finding, for both clinical practice and research, is that fatigue assessment must consider this multi-dimensionality. This is not unlike pain in fibromyalgia, which is increasingly demonstrated to be multidimensional, with contributions from central pain, peripheral musculoskeletal pain generators, and neuropathic pain, among other pathways [30].

The association of objective tests assessing the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, and corticotropin releasing factor in the cerebrospinal fluid with fatigue have been negative or inconclusive [38, 45, 46]. However, preliminary studies indicate that histological characteristics of skeletal muscle, such as muscle fiber distribution and capillary density, may be correlated with post-exertional malaise [47]. More recently, genomic studies have sought to identify possible physiologic pathways to explain the symptoms experienced by patients with fibromyalgia. Gene expression studies suggest the significant role of the catechol-O-methyltransferase, cytokine, adrenergic, dopamine, glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors, iron channel receptors and serotonin transporter in developing and maintaining the symptom complex [48, 49]. However, most of the early studies were conducted using pre-selected gene single nucleotide polymorphisms, which may introduce selection bias in assuming the disease etiology of fibromyalgia. One recent study investigating whole genome expression in patients with fibromyalgia with fatigue found an upregulation of centromere protein K (CENPK) and heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha (cytosolic, class A member 1 (HSP90AA1)) genes in fibromyalgia subjects when compared with age-, gender-, and race-matched healthy controls [50]. These genes are associated with glucocorticoid receptor signaling and the protein ubiquitination pathway (GIN1, GRAMD1C, ZNF880, NFYB, CENPK, CA1, and TNS1) [51]. Impairment of the ubiquitination pathways has been demonstrated to be associated with neurodegenerative diseases (for example, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease) and depression [52]. Additionally, interferon signaling and interferon regulatory pathways (associated with spinal nociception) distinguished between the pain groups, and dendritic cell maturation (associated with mood) delineated between the catastrophizing groups [50]. Collectively, these studies suggest that multiple physiological mechanisms may be associated with the symptom of fatigue.

Fatigue assessment

In the absence of objective biomarkers, assessment of fatigue is guided solely by patient-reported symptoms. Presently, there are no algorithms with which to systematically assess and treat fatigue. As noted, assessment must consider fatigue’s multidimensional manifestations. In clinical practice, therefore, evaluation of fatigue must account for both the experience of fatigue, as well as its functional impact, and place these in the context of other symptoms and co-morbidities specific to the particular patient.

The assessment begins with a thorough history and physical examination (to identify reversible causes of fatigue), and a systematic symptom-centered assessment pertaining not only to fatigue but also to pain, sleep, autonomic symptoms, causes of unrefreshing sleep (for example, obstructive sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome), psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety, and inquiry into health behaviors, daily practices, such as physical activity, and dietary habits (Figure 2). Table 2 illustrates common fibromyalgia symptoms, sample assessment tools, conditions to consider and suggestions for objective tests to evaluate abnormal symptoms.

A sample systematic symptom-centered assessment of fatigue. POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; tbl 2, Table 2.

In the research setting, in the absence of an objective measure, fatigue in fibromyalgia can only be assessed with validated, self-report questionnaires. Although the OMERACT Fibromyalgia Working Group recommends the assessment of fatigue in all clinical trials of fibromyalgia, no measure specific to fibromyalgia fatigue has been developed to date [12]. Fatigue assessment in clinical trials has utilized single item measures (visual analog scale - fatigue), multidimensional fatigue measures (for example, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory and Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue), or single items from composite measures, such as the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire - Revised and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 [54, 55, 63–66] (Table 3). Notably, most of these questionnaires were created for the assessment of fatigue in other chronic disorders such as cancer and rheumatologic conditions and have yet to be validated for fibromyalgia, with the exception of the single-item fatigue visual analog scale [63].

Debate also remains concerning the aspects of fatigue that must be assessed and whether measurement of fatigue requires subsets of questions targeting its separate manifestations (for example, global, somatic, affective, cognitive, and behavioral). Ongoing work from PROMIS and other groups will bring clarity to these issues. Until then, when selecting a fatigue questionnaire, researchers must consider its purpose. If the questionnaire is to be used as a screening tool, a shorter, single-item measure may be appropriate, or if the need is to evaluate an intervention, a multidimensional scale may be more appropriate.

Fatigue management

Our current understanding of the pathophysiology of fatigue suggests that its management in patients with fibromyalgia is most successful if developed by a multidisciplinary team with the patient as an equal participant. The treatment program should be individualized, and likely will incorporate combinations of behavioral, pharmacological, and rehabilitative interventions. Management is not aimed at the etiology of fatigue; rather, the focus is on symptoms, contributing factors, and treatment of comorbidities. Clinical experience suggests that a step-wise approach integrating different modalities with periodic assessment is ideal. This approach should be continued until clinically meaningful symptom improvement is achieved.

Non-pharmacologic and behavioral modalities

Care should always begin with patient education on the nature of fatigue and fibromyalgia, setting pragmatic goals for symptom reduction, and improvement of function. Patient education can include strategies such as pacing, energy conservation, increasing lifestyle physical activity, getting regular exercise, rest-activity balance, balanced diet, lifestyle moderation, stress management, time management, and sleep hygiene. As previously mentioned, daily symptom logs can help identify activities that exacerbate fatigue and other fibromyalgia symptoms. They can also guide individualization of non-pharmacological modalities. A selected listing of pharmacological and non-pharmacological clinical trials conducted in fibromyalgia where fatigue was also assessed is given in Tables 4, 5 and 6. In all of these studies, fatigue was only assessed as a secondary outcome (pain was primary). Even so, clinically meaningful changes in fatigue were demonstrated in some of these efficacy studies. This indicates that treatment modalities studied in the context of fibromyalgia could also be utilized to improve fatigue.

Non-pharmacological symptom management modalities, such as graded aerobic exercise, have demonstrated beneficial effects on physical capacity and fibromyalgia symptoms, including fatigue [73, 74] (Table 4). Combining aerobic exercise with resistance and strength training may offer additional benefits [146, 147]. Cognitive behavioral-based therapies (particularly for comorbid depression, anxiety, and pain), meditative movement therapies (for example, tai chi, yoga, qigong) and education sessions led by occupational therapists to enable patients to identify individual lifestyle factors that exacerbate fatigue and develop appropriate fatigue management and energy conservation techniques have good efficacy data [51, 148–150]. As with medications that require an adequate dose and duration for clinical efficacy, non-pharmacological modalities will only be effective if they are adequately dosed over the period of time that is required for physical, cognitive, and psychological rehabilitation. In most cases this may require several months and a step-wise, graded approach. Patients should be educated upfront to optimize success and compliance with the management strategy. Complementary and alternative therapies, such as acupuncture and homeopathy, have not demonstrated benefit in clinical studies, although patients commonly utilize these modalities, citing clinical benefit [151]. Carefully designed future trials will shed light on their use.

Pharmacologic modalities

Trials of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics, and alpha-2 delta ligands that impact multiple fibromyalgia symptoms suggest that these medications could also improve the symptom of fatigue (Tables 5 and 6). The choice of medication depends on the patient’s comorbid symptoms and use of a single medication to address multiple symptoms may be beneficial to minimize side effects. For example, in a fatigued patient with fibromyalgia with comorbid depression, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or tricyclics that have a differential effect on mood may be the pharmacological agent of choice. On the other hand, an alpha-2-delta ligand or a tricyclic may be more appropriate for a patient with comorbid unrefreshing sleep. If insomnia and unrefreshing sleep are the most bothersome symptoms for the patient, then targeting this symptom domain alone may improve both sleep and fatigue. Central nervous system stimulants may be most appropriate for patients with fatigue and comorbid narcolepsy. Though this class of medications is widely adopted in clinical practices to help patients with function, there are not enough data to support this practice [52, 123, 152]. Despite the demonstrated efficacy of some of these pharmacological agents, the clinician should be mindful that not all patients with fibromyalgia can tolerate medications. Medication sensitivity and medication intolerance is a major patient concern. Judicious use of lower doses of medication with frequent assessment for efficacy and side effects may help some patients [153].

Botanicals and dietary supplements

Botanicals, such as ginseng, and dietary supplements, such as coenzyme Q10, s-adenosyl methionine and acetyl-l-carnitine, have been posited to relieve fatigue [120, 140, 144, 145] (Table 6). Although these agents are largely devoid of the side effect profile of pharmacologic agents, only preliminary efficacy data are available.

Conclusion

Fatigue is a complex symptom that is differentially experienced by individual patients with fibromyalgia depending on their genetic, biological, and psychosocial makeup, self-efficacy and emotional regulatory capacity, and presence of comorbidities. The profile of fatigue in fibromyalgia is similar to that in many chronic conditions, although the presence of fibromyalgia with other rheumatological conditions seems to intensify fatigue [154, 155]. A commonly observed theme in the literature is the co-occurrence of fatigue with other centrally mediated symptoms such as pain, unrefreshing sleep, affective symptoms, and the influence of psychosocial variables. This may imply that the same central mechanisms that drive pain, mood, and sleep also drive fatigue. Given that these symptoms (for example, pain, fatigue, sleep) occur concurrently, we tend to assume that they manifest at the same level. This may not be an accurate way to view fatigue. It may be that fatigue is a higher order construct, or meta-construct that is fed by other, more discrete symptoms. Only further inquiry will address these questions.

At the clinical level, given our current limitations, fatigue management is best facilitated by conducting a nuanced fatigue assessment in routine clinical encounters to include a thoughtful history and investigation for treatable causes of fatigue, and screening for fatigue and other common comorbid fibromyalgia symptoms such as pain, anxiety, depression, sleep, and stress. Fatigue assessment and management can also be enhanced by encouraging patients to keep symptom logs to gain insights into lag relationships among symptoms, educating patients about the nature of fatigue, and setting realistic goals for symptom management (that is, focus on decreasing the impact of symptoms and improve function rather than symptom alleviation alone).

From a research perspective, a disease-specific fatigue measure for fibromyalgia is needed to move the field forward. Additionally, studies to understand mechanisms (for example, biological, physiological, or psychological) and management of fatigue are also needed. As the study of fatigue in fibromyalgia advances, multidisciplinary collaborations that are patient-centered and facilitate patient engagement will guide treatment options to provide relief.

Note

This article is part of the series on New perspectives in fibromyalgia, edited by Daniel Clauw. Other articles in this series can be found at http://arthritis-research.com/series/fibromyalgia

Abbreviations

- CENPK:

-

Centromere protein K

- OMERACT:

-

Outcome Measures in Rheumatology

- PROMIS:

-

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- PROMIS-FIB:

-

PROMIS Fatigue Item Bank

References

Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L: The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38: 19-28. 10.1002/art.1780380104.

Chandran AB, Schaefer C, Ryan K, Baik R, McNett M, Zlateva G: The comparative economic burden of mild, moderate, and severe fibromyalgia: results from a retrospective chart review and cross-sectional survey of working-age US adults. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012, 18: 415-426.

Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, McCarberg BH: Improving the recognition and diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011, 86: 457-464. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0738.

Mease PJ, Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, Williams DA, Russell IJ, Humphrey L, Abetz L, Martin SA: Identifying the clinical domains of fibromyalgia: contributions from clinician and patient Delphi exercises. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59: 952-960. 10.1002/art.23826.

Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Wilson K: The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996, 23: 1407-1417.

Walitt B, Fitzcharles M-A, Hassett AL, Katz RS, Hauser W, Wolfe F: The longitudinal outcome of fibromyalgia: a study of 1555 patients. J Rheumatol. 2011, 38: 2238-2246. 10.3899/jrheum.110026.

Wolfe F, Anderson J, Harkness D, Bennett RM, Caro XJ, Goldenberg DL, Russell IJ, Yunus MB: Health status and disease severity in fibromyalgia: results of a six-center longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 1571-1579. 10.1002/art.1780400905.

Humphrey L, Arbuckle R, Mease P, Williams DA, Samsoe BD, Gilbert C: Fatigue in fibromyalgia: a conceptual model informed by patient interviews. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010, 11: 216-10.1186/1471-2474-11-216.

Connolly D, O'Toole L, Redmond P, Smith SM: Managing fatigue in patients with chronic conditions in primary care. Fam Pract. 2013, 30: 123-124. 10.1093/fampra/cmt005.

Sharpe M, Wilks D: Fatigue. BMJ. 2002, 325: 480-483. 10.1136/bmj.325.7362.480.

Nijrolder I, van der Windt DAWM, van der Horst HE: Prognosis of fatigue and functioning in primary care: a 1-year follow-up study. Ann Fam Med. 2008, 6: 519-527. 10.1370/afm.908.

Mease P, Arnold LM, Choy EH, Clauw DJ, Crofford LJ, Glass JM, Martin SA, Morea J, Simon L, Strand CV, Williams DA, OMERACT Fibromyalgia Working Group: Fibromyalgia syndrome module at OMERACT 9: domain construct. J Rheumatol. 2009, 36: 2318-2329. 10.3899/jrheum.090367.

Choy EH: Clinical domains of fibromyalgia syndrome: determination through the OMERACT process. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2010, 18: 380-386. 10.3109/10582452.2010.502623.

Choy EH, Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, Crofford LJ, Glass JM, Simon LS, Martin SA, Strand CV, Williams DA, Mease PJ: Content and criterion validity of the preliminary core dataset for clinical trials in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2009, 36: 2330-2334. 10.3899/jrheum.090368.

Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Christensen R, Crofford LJ, Gendreau RM, Martin SA, Simon LS, Strand V, Williams DA, Arnold LM, OMERACT Fibromyalgia Working Group: Toward development of a fibromyalgia responder index and disease activity score: OMERACT module update. J Rheumatol. 2011, 38: 1487-1495. 10.3899/jrheum.110277.

Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, Fries JF, Bruce B, Rose M, PROMIS Cooperative Group: The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007, 45: S3-S11.

Lai JS, Cella D, Choi S, Junghaenel DU, Christodoulou C, Gershon R, Stone A: How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: a PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011, 92: S20-S27. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.033.

Soderberg S, Lundman B, Norberg A: The meaning of fatigue and tiredness as narrated by women with fibromyalgia and healthy women. J Clin Nurs. 2002, 11: 247-255. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00606.x.

Sturge-Jacobs M: The experience of living with fibromyalgia: confronting an invisible disability. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2002, 16: 19-31. 10.1891/rtnp.16.1.19.52994.

Yunus MB, Inanici F, Aldag JC, Mangold RF: Fibromyalgia in men: comparison of clinical features with women. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27: 485-490.

Nicassio PM, Moxham EG, Schuman CE, Gevirtz RN: The contribution of pain, reported sleep quality, and depressive symptoms to fatigue in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2002, 100: 271-279. 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00300-7.

Nicassio PM, Schuman CC: The prediction of fatigue in fibromyalgia. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2005, 13: 15-25. 10.1300/J094v13n01_03.

Finan PH, Zautra AJ: Fibromyalgia and fatigue: central processing, widespread dysfunction. PM R. 2010, 2: 431-437. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.021.

Arranz L, Canela MA, Rafecas M: Relationship between body mass index, fat mass and lean mass with SF-36 quality of life scores in a group of fibromyalgia patients. Rheumatol Int. 2012, 32: 3605-3611. 10.1007/s00296-011-2250-y.

Guymer EK, Maruff P, Littlejohn GO: Clinical characteristics of 150 consecutive fibromyalgia patients attending an Australian public hospital clinic. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012, 15: 348-357. 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01767.x.

Finan PH, Zautra AJ, Davis MC: Daily affect relations in fibromyalgia patients reveal positive affective disturbance. Psychosom Med. 2009, 71: 474-482. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819e0a8b.

Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Reich JW: Vulnerability to stress among women in chronic pain from fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis. Ann Behav Med. 2001, 23: 215-226. 10.1207/S15324796ABM2303_9.

Bellamy N, Sothern RB, Campbell J: Aspects of diurnal rhythmicity in pain, stiffness, and fatigue in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2004, 31: 379-389.

Zautra AJ, Fasman R, Parish BP, Davis MC: Daily fatigue in women with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Pain. 2007, 128: 128-135. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.004.

Staud R: Peripheral pain mechanisms in chronic widespread pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011, 25: 155-164. 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.010.

Kurtze N, Svebak S: Fatigue and patterns of pain in fibromyalgia: correlations with anxiety, depression and co-morbidity in a female county sample. Br J Med Psychol. 2001, 74: 523-537. 10.1348/000711201161163.

Hughes L: Physical and psychological variables that influence pain in patients with fibromyalgia. Orthop Nurs. 2006, 25: 112-119. quiz 120–111

Wolfe F: Determinants of WOMAC function, pain and stiffness scores: evidence for the role of low back pain, symptom counts, fatigue and depression in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999, 38: 355-361. 10.1093/rheumatology/38.4.355.

Hamilton NA, Affleck G, Tennen H, Karlson C, Luxton D, Preacher KJ, Templin JL: Fibromyalgia: the role of sleep in affect and in negative event reactivity and recovery. Health Psychol. 2008, 27: 490-497.

Parrish BP, Zautra AJ, Davis MC: The role of positive and negative interpersonal events on daily fatigue in women with fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis. Health Psychol. 2008, 27: 694-702.

Okifuji A, Bradshaw DH, Donaldson GW, Turk DC: Sequential analyses of daily symptoms in women with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2011, 12: 84-93. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.05.003.

Landis CA, Frey CA, Lentz MJ, Rothermel J, Buchwald D, Shaver JLF: Self-reported sleep quality and fatigue correlates with actigraphy in midlife women with fibromyalgia. Nurs Res. 2003, 52: 140-147. 10.1097/00006199-200305000-00002.

Gur A, Cevik R, Sarac AJ, Colpan L, Em S: Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and cortisol in young women with primary fibromyalgia: the potential roles of depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in the occurrence of hypocortisolism. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63: 1504-1506. 10.1136/ard.2003.014969.

White KP, Nielson WR, Harth M, Ostbye T, Speechley M: Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain with or without fibromyalgia: psychological distress in a representative community adult sample. J Rheumatol. 2002, 29: 588-594.

Kurtze N, Gundersen KT, Svebak S: The role of anxiety and depression in fatigue and patterns of pain among subgroups of fibromyalgia patients. Br J Med Psychol. 1998, 71: 185-194. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1998.tb01379.x.

Suhr JA: Neuropsychological impairment in fibromyalgia: relation to depression, fatigue, and pain. J Psychosom Res. 2003, 55: 321-329. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00628-1.

Droegemueller CJ, Brauer DJ, van Buskirk DJ: Temperament and fatigue management in persons with chronic rheumatic disease. Clin Nurse Spec. 2008, 22: 19-27. 10.1097/01.NUR.0000304180.59439.48. quiz 28–29

Malin K, Littlejohn GO: Psychological control is a key modulator of fibromyalgia symptoms and comorbidities. J Pain Res. 2012, 5: 463-471.

Schaefer C, Chandran A, Hufstader M, Baik R, McNett M, Goldenberg D, Gerwin R, Zlateva G: The comparative burden of mild, moderate and severe fibromyalgia: results from a cross-sectional survey in the United States. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011, 9: 71-10.1186/1477-7525-9-71.

McLean SA, Williams DA, Harris RE, Kop WJ, Groner KH, Ambrose K, Lyden AK, Gracely RH, Crofford LJ, Geisser ME, Sen A, Biswas P, Clauw DJ: Momentary relationship between cortisol secretion and symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 3660-3669. 10.1002/art.21372.

McLean SA, Williams DA, Stein PK, Harris RE, Lyden AK, Whalen G, Park KM, Liberzon I, Sen A, Gracely RH, Baraniuk JN, Clauw DJ: Cerebrospinal fluid corticotropin-releasing factor concentration is associated with pain but not fatigue symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006, 31: 2776-2782. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301200.

Srikuea R, Symons TB, Long DE, Lee JD, Shang Y, Chomentowski PJ, Yu G, Crofford LJ, Peterson CA: Association of fibromyalgia with altered skeletal muscle characteristics which may contribute to postexertional fatigue in postmenopausal women. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65: 519-528. 10.1002/art.37763.

Light KC, White AT, Tadler S, Iacob E, Light AR: Genetics and gene expression involving stress and distress pathways in fibromyalgia with and without comorbid chronic fatigue syndrome. Pain Res Treat. 2012, 2012: 427869-

Swain MG: Fatigue in chronic disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2000, 99: 1-8. 10.1042/CS19990372.

Lukkahatai N, Majors B, Reddy S, Walitt B, Saligan LN: Gene expression profiles of fatigued fibromyalgia patients with different categories of pain and catastrophizing: a preliminary report. Nurs Outlook. 2013, 61: 216-224. 10.1016/j.outlook.2013.03.007. e2

O'Toole L, Connolly D, Smith S: Impact of an occupation-based self-management programme on chronic disease management. Aust Occup Ther J. 2013, 60: 30-38. 10.1111/1440-1630.12008.

Schwartz TL, Rayancha S, Rashid A, Chlebowksi S, Chilton M, Morell M: Modafinil treatment for fatigue associated with fibromyalgia. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007, 13: 52-10.1097/01.rhu.0000255801.32408.6e.

Cleeland CS, Ryan KM: Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994, 23: 129-138.

Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC: The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995, 39: 315-325. 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-O.

Ware JE: SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000, 25: 3130-3139. 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992, 30: 473-483. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lowe B: A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Int Med. 2006, 166: 1092-1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001, 16: 606-613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Smarr KL, Keefer AL: Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63: S454-S466. 10.1002/acr.20556.

Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale. Appl Psychol Measurement. 1977, 1: 385-401. 10.1177/014662167700100306.

Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W: COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated Composite Autonomic Symptom Score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012, 87: 1196-1201. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013.

Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, McDermott AM, Dukes E, Sadosky A, Petrie CD, Martin S: Measurement properties of the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale in patients with fibromyalgia. Sleep Med. 2009, 10: 766-770. 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.09.004.

Crawford BK, Piault EC, Lai C, Bennett RM: Assessing fibromyalgia-related fatigue: content validity and psychometric performance of the Fatigue Visual Analog Scale in adult patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011, 29: S34-S43.

Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF). [http://www.son.washington.edu/research/maf/default.asp]

Bennett RM, Friend R, Jones KD, Ward R, Han BK, Ross RL: The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009, 11: R120-10.1186/ar2783. A published erratum appears in Arthritis Res Ther 2009, 11:415

Hewlett S, Dures E, Almeida C: Measures of fatigue: Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional Questionnaire (BRAF MDQ), Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Numerical Rating Scales (BRAF NRS) for severity, effect, and coping, Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ), Checklist Individual Strength (CIS20R and CIS8R), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Functional Assessment Chronic Illness Therapy (Fatigue) (FACIT-F), Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF), Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), Pediatric Quality Of Life (PedsQL) Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Scale, Profile of Fatigue (ProF), Short Form 36 Vitality Subscale (SF-36 VT), and Visual Analog Scales (VAS). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63: S263-S286. 10.1002/acr.20579.

Cella M, Chalder T: Measuring fatigue in clinical and community settings. J Psychosom Res. 2010, 69: 17-22. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.007.

Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, Wallace EP: Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993, 37: 147-153. 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P.

Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Fennis JF, Galama JM, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G: Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1994, 38: 383-392. 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90099-X.

Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD: The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989, 46: 1121-1123. 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022.

Lera S, Gelman SM, Lopez MJ, Abenoza M, Zorrilla JG, Castro-Fornieles J, Salamero M: Multidisciplinary treatment of fibromyalgia: does cognitive behavior therapy increase the response to treatment?. J Psychosom Res. 2009, 67: 433-441. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.012.

Karper WB, Stasik SC: A successful, long-term exercise program for women with fibromyalgia syndrome and chronic fatigue and immune dysfunction syndrome. Clin Nurse Spec. 2003, 17: 243-248. 10.1097/00002800-200309000-00008.

Hauser W, Klose P, Langhorst J, Moradi B, Steinbach M, Schiltenwolf M, Busch A: Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010, 12: R79-10.1186/ar3002.

Busch AJ, Schachter CL, Overend TJ, Peloso PM, Barber KA: Exercise for fibromyalgia: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2008, 35: 1130-1144.

Valkeinen H, Alen M, Hakkinen A, Hannonen P, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Hakkinen K: Effects of concurrent strength and endurance training on physical fitness and symptoms in postmenopausal women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008, 89: 1660-1666. 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.022.

Bircan C, Karasel SA, Akgun B, El O, Alper S: Effects of muscle strengthening versus aerobic exercise program in fibromyalgia. Rheumatol Int. 2008, 28: 527-532. 10.1007/s00296-007-0484-5.

Hakkinen A, Hakkinen K, Hannonen P, Alen M: Strength training induced adaptations in neuromuscular function of premenopausal women with fibromyalgia: comparison with healthy women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001, 60: 21-26. 10.1136/ard.60.1.21.

van Wilgen CP, Bloten H, Oeseburg B: Results of a multidisciplinary program for patients with fibromyalgia implemented in the primary care. Disabil Rehabil. 2007, 29: 1207-1213. 10.1080/09638280600949860.

Havermark AM, Langius-Eklof A: Long-term follow up of a physical therapy programme for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006, 20: 315-322. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00410.x.

Cedraschi C, Desmeules J, Rapiti E, Baumgartner E, Cohen P, Finckh A, Allaz AF, Vischer TL: Fibromyalgia: a randomised, controlled trial of a treatment programme based on self management. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63: 290-296. 10.1136/ard.2002.004945.

Mannerkorpi K, Nyberg B, Ahlmen M, Ekdahl C: Pool exercise combined with an education program for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. A prospective, randomized study. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27: 2473-2481.

Luciano JV, Martínez N, Peñarrubia-María MT, Fernández-Vergel R, García-Campayo J, Verduras C, Blanco ME, Jiménez M, Ruiz JM, López del Hoyo Y, Serrano-Blanco A, FibroQoL Study Group: Effectiveness of a psychoeducational treatment program implemented in general practice for fibromyalgia patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2011, 27: 383-391. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31820b131c.

Carbonell-Baeza A, Aparicio VA, Chillon P, Femia P, Delgado-Fernandez M, Ruiz JR: Effectiveness of multidisciplinary therapy on symptomatology and quality of life in women with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011, 29: S97-S103.

Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K: The internet-based arthritis self-management program: a one-year randomized trial for patients with arthritis or fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59: 1009-1017. 10.1002/art.23817.

Hauser W, Bernardy K, Arnold B, Offenbacher M, Schiltenwolf M: Efficacy of multicomponent treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61: 216-224. 10.1002/art.24276.

Langhorst J, Klose P, Musial F, Irnich D, Hauser W: Efficacy of acupuncture in fibromyalgia syndrome - a systematic review with a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010, 49: 778-788. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep439.

Langhorst J, Klose P, Dobos GJ, Bernardy K, Hauser W: Efficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int. 2013, 33: 193-207. 10.1007/s00296-012-2360-1.

Arnold LM, Wang F, Ahl J, Gaynor PJ, Wohlreich MM: Improvement in multiple dimensions of fatigue in patients with fibromyalgia treated with duloxetine: secondary analysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011, 13: R86-10.1186/ar3359.

Chappell AS, Bradley LA, Wiltse C, Detke MJ, D'Souza DN, Spaeth M: A six-month double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of duloxetine for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Int J Gen Med. 2008, 1: 91-102.

Arnold LM, Lu Y, Crofford LJ, Wohlreich M, Detke MJ, Iyengar S, Goldstein DJ: A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major depressive disorder. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 2974-2984. 10.1002/art.20485.

Clauw DJ, Mease P, Palmer RH, Gendreau RM, Wang Y: Milnacipran for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults: a 15-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2008, 30: 1988-2004. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.11.009.

Branco JC, Zachrisson O, Perrot S, Mainguy Y: A European multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled monotherapy clinical trial of milnacipran in treatment of fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2010, 37: 851-859. 10.3899/jrheum.090884.

Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Gendreau RM, Rao SG, Kranzler J, Chen W, Palmer RH: The efficacy and safety of milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009, 36: 398-409. 10.3899/jrheum.080734. Published erratum appears in J Rheumatol 2009, 36:661

Gendreau RM, Thorn MD, Gendreau JF, Kranzler JD, Ribeiro S, Gracely RH, Williams DA, Mease PJ, McLean SA, Clauw DJ: Efficacy of milnacipran in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32: 1975-1985.

Arnold LM, Gendreau RM, Palmer RH, Gendreau JF, Wang Y: Efficacy and safety of milnacipran 100 mg/day in patients with fibromyalgia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 2745-2756. 10.1002/art.27559.

Vitton O, Gendreau M, Gendreau J, Kranzler J, Rao SG: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of milnacipran in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004, 19: S27-S35. 10.1002/hup.622.

Branco JC, Cherin P, Montagne A, Bouroubi A: Long-term therapeutic response to milnacipran treatment for fibromyalgia. A European 1-year extension study following a 3-month study. J Rheumatol. 2011, 38: 1403-1412. 10.3899/jrheum.101025.

Pauer L, Atkinson G, Murphy TK, Petersel D, Zeiher B: Long-term maintenance of response across multiple fibromyalgia symptom domains in a randomized withdrawal study of pregabalin. Clin J Pain. 2012, 28: 609-614. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31823dd315.

Mease PJ, Russell IJ, Arnold LM, Florian H, Young JP, Martin SA, Sharma U: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of pregabalin in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2008, 35: 502-514.

Crofford LJ, Rowbotham MC, Mease PJ, Russell IJ, Dworkin RH, Corbin AE, Young JP, LaMoreaux LK, Martin SA, Sharma U, Pregabalin 1008–105 Study Group: Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 1264-1273. 10.1002/art.20983.

Donmez A, Karagulle MZ, Tercan N, Dinler M, Issever H, Karagulle M, Turan M: SPA therapy in fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled clinic study. Rheumatol Int. 2005, 26: 168-172. 10.1007/s00296-005-0623-9.

Altan L, Bingol U, Aykac M, Koc Z, Yurtkuran M: Investigation of the effects of pool-based exercise on fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2004, 24: 272-277.

Buskila D, Abu-Shakra M, Neumann L, Odes L, Shneider E, Flusser D, Sukenik S: Balneotherapy for fibromyalgia at the Dead Sea. Rheumatol Int. 2001, 20: 105-108. 10.1007/s002960000085.

Huuhka MJ, Haanpaa ML, Leinonen EV: Electroconvulsive therapy in patients with depression and fibromyalgia. Eur J Pain. 2004, 8: 371-376. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.11.001.

Gur A, Karakoc M, Nas K, Cevik R, Sarac J, Demir E: Efficacy of low power laser therapy in fibromyalgia: a single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2002, 17: 57-61. 10.1007/s10103-002-8267-4.

Gur A, Karakoc M, Nas K, Cevik R, Sarac J, Ataoglu S: Effects of low power laser and low dose amitriptyline therapy on clinical symptoms and quality of life in fibromyalgia: a single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatol Int. 2002, 22: 188-193. 10.1007/s00296-002-0221-z.

Maddali Bongi S, Di Felice C, Del Rosso A, Landi G, Maresca M, Giambalvo Dal Ben G, Matucci-Cerinic M: Efficacy of the “body movement and perception” method in the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: an open pilot study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011, 29: S12-S18.

Hargrove JB, Bennett RM, Simons DG, Smith SJ, Nagpal S, Deering DE: A randomized placebo-controlled study of noninvasive cortical electrostimulation in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients. Pain Med. 2012, 13: 115-124. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01292.x.

Almeida TF, Roizenblatt S, Benedito-Silva AA, Tufik S: The effect of combined therapy (ultrasound and interferential current) on pain and sleep in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2003, 104: 665-672. 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00139-8.

Chen KW, Hassett AL, Hou F, Staller J, Lichtbroun AS: A pilot study of external qigong therapy for patients with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 2006, 12: 851-856. 10.1089/acm.2006.12.851.

Kayiran S, Dursun E, Dursun N, Ermutlu N, Karamursel S: Neurofeedback intervention in fibromyalgia syndrome; a randomized, controlled, rater blind clinical trial. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2010, 35: 293-302. 10.1007/s10484-010-9135-9.

Carbonario F, Matsutani LA, Yuan SL, Marques AP: Effectiveness of high-frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation at tender points as adjuvant therapy for patients with fibromyalgia. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013, 49: 197-204.

Mhalla A, Baudic S, Ciampi de Andrade D, Gautron M, Perrot S, Teixeira MJ, Attal N, Bouhassira D: Long-term maintenance of the analgesic effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2011, 152: 1478-1485. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.034.

Passard A, Attal N, Benadhira R, Brasseur L, Saba G, Sichere P, Perrot S, Januel D, Bouhassira D: Effects of unilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex on chronic widespread pain in fibromyalgia. Brain. 2007, 130: 2661-2670. 10.1093/brain/awm189.

Donaldson MS, Speight N, Loomis S: Fibromyalgia syndrome improved using a mostly raw vegetarian diet: an observational study. BMC Altern Med. 2001, 1: 7-10.1186/1472-6882-1-7.

Azad KA, Alam MN, Haq SA, Nahar S, Chowdhury MA, Ali SM, Ullah AK: Vegetarian diet in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2000, 26: 41-47.

Alentorn-Geli E, Padilla J, Moras G, Lazaro Haro C, Fernandez-Sola J: Six weeks of whole-body vibration exercise improves pain and fatigue in women with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 2008, 14: 975-981. 10.1089/acm.2008.0050.

Broderick JE, Junghaenel DU, Schwartz JE: Written emotional expression produces health benefits in fibromyalgia patients. Psychosom Med. 2005, 67: 326-334. 10.1097/01.psy.0000156933.04566.bd.

Carson JW, Carson KM, Jones KD, Bennett RM, Wright CL, Mist SD: A pilot randomized controlled trial of the Yoga of Awareness program in the management of fibromyalgia. Pain. 2010, 151: 530-539. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.020.

Braz AS, Morais LC, Paula AP, Diniz MF, Almeida RN: Effects of Panax ginseng extract in patients with fibromyalgia: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013, 35: 21-28. 10.1016/j.rbp.2013.01.004.

Nishishinya B, Urrutia G, Walitt B, Rodriguez A, Bonfill X, Alegre C, Darko G: Amitriptyline in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a systematic review of its efficacy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008, 47: 1741-1746. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken317.

Uceyler N, Hauser W, Sommer C: A systematic review on the effectiveness of treatment with antidepressants in fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59: 1279-1298. 10.1002/art.24000.

Schwartz TL, Siddiqui UA, Raza S, Morell M: Armodafinil for fibromyalgia fatigue. Ann Pharmacother. 2010, 44: 1347-1348. 10.1345/aph.1M736.

Tofferi JK, Jackson JL, O'Malley PG: Treatment of fibromyalgia with cyclobenzaprine: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 51: 9-13. 10.1002/art.20076.

Arnold LM, Hirsch I, Sanders P, Ellis A, Hughes B: Safety and efficacy of esreboxetine in patients with fibromyalgia: a fourteen-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64: 2387-2397. 10.1002/art.34390.

Arnold LM, Chatamra K, Hirsch I, Stoker M: Safety and efficacy of esreboxetine in patients with fibromyalgia: an 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2010, 32: 1618-1632. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.08.003.

Arnold LM, Hess EV, Hudson JI, Welge JA, Berno SE, Keck PE: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose study of fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2002, 112: 191-197. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)01089-0.

Scharf MB, Hauck M, Stover R, McDannold M, Berkowitz D: Effect of gamma-hydroxybutyrate on pain, fatigue, and the alpha sleep anomaly in patients with fibromyalgia. Preliminary report. J Rheumatol. 1998, 25: 1986-1990.

Russell IJ, Holman AJ, Swick TJ, Alvarez-Horine S, Wang YG, Guinta D: Sodium oxybate reduces pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance and improves functionality in fibromyalgia: results from a 14-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain. 2011, 152: 1007-1017. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.022.

Moldofsky H, Inhaber NH, Guinta DR, Alvarez-Horine SB: Effects of sodium oxybate on sleep physiology and sleep/wake-related symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Rheumatol. 2010, 37: 2156-2166. 10.3899/jrheum.091041.

Scharf MB, Baumann M, Berkowitz DV: The effects of sodium oxybate on clinical symptoms and sleep patterns in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30: 1070-1074.

Spitzer AR, Broadman M: Treatment of the narcoleptiform sleep disorder in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia with sodium oxybate. Pain Pract. 2010, 10: 54-59. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00334.x.

Samborski W, Lezanska-Szpera M, Rybakowski JK: Open trial of mirtazapine in patients with fibromyalgia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004, 37: 168-170. 10.1055/s-2004-827172.

Holman AJ, Myers RR: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, in patients with fibromyalgia receiving concomitant medications. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 2495-2505. 10.1002/art.21191.

Jones KD, Burckhardt CS, Deodhar AA, Perrin NA, Hanson GC, Bennett RM: A six-month randomized controlled trial of exercise and pyridostigmine in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 612-622. 10.1002/art.23203.

Hidalgo J, Rico-Villademoros F, Calandre EP: An open-label study of quetiapine in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 31: 71-77. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.06.023.

Sadreddini S, Molaeefard M, Noshad H, Ardalan M, Asadi A: Efficacy of Raloxifen in treatment of fibromyalgia in menopausal women. Eur J Intern Med. 2008, 19: 350-355. 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.10.006.

Stratz T, Farber L, Varga B, Baumgartner C, Haus U, Muller W: Fibromyalgia treatment with intravenous tropisetron administration. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2001, 27: 113-118.

Rossini M, Di Munno O, Valentini G, Bianchi G, Biasi G, Cacace E, Malesci D, La Montagna G, Viapiana O, Adami S: Double-blind, multicenter trial comparing acetyl l-carnitine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007, 25: 182-188.

Cordero MD, Alcocer-Gomez E, de Miguel M, Culic O, Carrion AM, Alvarez-Suarez JM, Bullon P, Battino M, Fernandez-Rodriguez A, Sanchez-Alcazar JA: Can coenzyme Q improve clinical and molecular parameters in fibromyalgia?. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013, 19: 1356-1361. 10.1089/ars.2013.5260.

Finckh A, Berner IC, Aubry-Rozier B, So AK: A randomized controlled trial of dehydroepiandrosterone in postmenopausal women with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32: 1336-1340.

Massey PB: Reduction of fibromyalgia symptoms through intravenous nutrient therapy: results of a pilot clinical trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007, 13: 32-34.

Citera G, Arias MA, Maldonado-Cocco JA, Lazaro MA, Rosemffet MG, Brusco LI, Scheines EJ, Cardinalli DP: The effect of melatonin in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Clin Rheum. 2000, 19: 9-13. 10.1007/s100670050003.

Volkmann H, Norregaard J, Jacobsen S, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, Knoke G, Nehrdich D: Double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study of intravenous S-adenosyl-L-methionine in patients with fibromyalgia. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997, 26: 206-211. 10.3109/03009749709065682.

Jacobsen S, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, Andersen RB: Oral S-adenosylmethionine in primary fibromyalgia. Double-blind clinical evaluation. Scand J Rheumatol. 1991, 20: 294-302. 10.3109/03009749109096803.

Geel SE, Robergs RA: The effect of graded resistance exercise on fibromyalgia symptoms and muscle bioenergetics: a pilot study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 47: 82-86. 10.1002/art1.10240.

Sanudo B, Galiano D, Carrasco L, Blagojevic M, de Hoyo M, Saxton J: Aerobic exercise versus combined exercise therapy in women with fibromyalgia syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010, 91: 1838-1843. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.09.006.

Kollner V, Hauser W, Klimczyk K, Kuhn-Becker H, Settan M, Weigl M, Bernardy K: Psychotherapy for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline. Schmerz. 2012, 26: 291-296. 10.1007/s00482-012-1179-8.

Nuesch E, Hauser W, Bernardy K, Barth J, Juni P: Comparative efficacy of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions in fibromyalgia syndrome: network meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013, 72: 955-962. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201249.

Lami MJ, Martinez MP, Sanchez AI: Systematic review of psychological treatment in fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013, 17: 345-

Langhorst J, Hauser W, Bernardy K, Lucius H, Settan M, Winkelmann A, Musial F: Complementary and alternative therapies for fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline. Schmerz. 2012, 26: 311-317. 10.1007/s00482-012-1178-9.

Frost J, Okun S, Vaughan T, Heywood J, Wicks P: Patient-reported outcomes as a source of evidence in off-label prescribing: analysis of data from PatientsLikeMe. J Med Internet Res. 2011, 13: e6-10.2196/jmir.1643.

Fitzcharles MA, Ste-Marie PA, Goldenberg DL, Pereira JX, Abbey S, Choinière M, Ko G, Moulin DE, Panopalis P, Proulx J, Shir Y, National Fibromyalgia Guideline Advisory Panel: Canadian Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia syndrome: Executive summary. Pain Res Manag. 2012, 2013: 119-126.

Priori R, Iannuccelli C, Alessandri C, Modesti M, Antonazzo B, Di Lollo AC, Valesini G, Di Franco M: Fatigue in Sjogren’s syndrome: relationship with fibromyalgia, clinical and biologic features. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010, 28: S82-S86.

Iannuccelli C, Spinelli FR, Guzzo MP, Priori R, Conti F, Ceccarelli F, Pietropaolo M, Olivieri M, Minniti A, Alessandri C, Gattamelata A, Valesini G, Di Franco M: Fatigue and widespread pain in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren’s syndrome: symptoms of the inflammatory disease or associated fibromyalgia?. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012, 30: 117-121.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the Center for Translational Science Activities (CTSA) at Mayo Clinic. This center is funded in part by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (RR024150). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of CTSA, NCRR, or NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vincent, A., Benzo, R.P., Whipple, M.O. et al. Beyond pain in fibromyalgia: insights into the symptom of fatigue. Arthritis Res Ther 15, 221 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4395

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4395