Abstract

Background

The majority of patients with chondrosarcoma of bone have an excellent overall survival after local therapy. However, in case of unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease the outcome is poor and limited treatment options exist. Therefore we conducted a survey of clinical phase I or II trials and retrospective studies that described systemic therapy for chondrosarcoma patients.

Materials and methods

Using PubMed, clinicaltrials.gov, the Cochrane controlled trial register and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) abstracts a literature survey was conducted. From the identified items, data were collected by a systematic analysis. We limited our search to semi-recent studies published between 2000 and 2013 to include modern drugs, imaging techniques and disease evaluations.

Results

A total of 31 studies were found which met the criteria: 9 phase I trials, 11 phase II and 8 retrospective studies. In these studies 855 chondrosarcoma patients were reported. The tested drugs were mostly non-cytotoxic, either alone or in combination with another non-cytotoxic agent or chemotherapy. Currently two phase I trials, one phase IB/II trial and three phase II trials are enrolling chondrosarcoma patients.

Conclusion

Because chondrosarcoma of bone is an orphan disease it is difficult to conduct clinical trials. The meagre outcome data for locally advanced or metastatic patients indicate that new treatment options are needed. For the phase I trials it is difficult to draw conclusions because of the low numbers of chondrosarcoma patients enrolled, and at different dose levels. Some phase II trials show promising results which support further research. Retrospective studies are encouraged as they could add to the limited data available. Efforts to increase the number of studies for this orphan disease are urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chondrosarcoma (CS) is the second most common primary bone sarcoma in humans, but with an estimated incidence of 0.2 in 100.000 patients per year it is still a very rare disease[1]. CS mostly affects adults between the age of 20 and 60[2]. CS belong to a very diverse group of tumors having in common the production of cartilaginous matrix. Almost 90% of the CS are of the conventional subtype, but there are also the more rare subtypes with their own distinct histological and clinical features including clear cell, mesenchymal and dedifferentiated CS[3]. The prognosis for patients with CS is very diverse with a very good prognosis for atypical cartilaginous tumour/CS grade I which are slow growing and do not metastasize and a poor prognosis for grade III CS which have a high risk, up to 70%, for local recurrence and metastasis[4, 5]. Currently the most commonly used treatment option for atypical cartilaginous tumour/CS grade I is curettage with local adjuvants which is usually enough to cure the patient. However, for grade II and grade III CS en bloc resection is required. If a patient has unresectable or metastasized disease the current treatment options are very limited. CS has always been considered to be chemotherapy and radiotherapy resistant and it was assumed that patients would not benefit from non-surgical treatment. However, new preclinical work and retrospective studies show that there may be a place for non-cytotoxic, chemo- and radiotherapy in the treatment of CS[6, 7]. In the last decades more knowledge has become available about the molecular background of the different CS subtypes (for review see[8–10]). Investigators have been trying to find new systemic treatment options for these patients through phase I and II clinical trials (no phase III studies were ever conducted). Because CS is such a rare disease, and high grade metastatic or unresectable disease is even more uncommon, the number of patients in these trials is however low and thereby it is difficult to give a clear answer to the question whether a new drug improves outcome or not. Here we report an overview of a survey we conducted on published and presented phase I and II clinical trials and retrospective studies on systemic therapy enrolling CS patients, published from 2000 until 2013. We also include the studies that are enrolling patients at this moment.

Material and methods

Search strategy

To collect phase I and II and retrospective studies which included CS patients we used the search machines PubMed, clinicaltrials.gov, the Cochrane controlled trial register and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) abstracts. For the search criteria we used the terms [chondrosarcoma] AND [phase I OR phase II OR retrospective] AND [clinical trial]. To check for missed articles we widened the search to [sarcoma] AND [phase I OR phase II] AND [clinical trial] and compared the results. When multiple reports from the same trial were published we only used the article with the longest follow up time. Publications were used if they 1) described results from an early phase clinical trial in which CS patients were included, either prospective or retrospective, 2) were written in English. The latest search was performed in December 2013. Studies on extraskeletal myxoid CS were excluded.

Data were collected from trials published between 2000 and 2013 to include modern drugs, imaging techniques and disease evaluations. Data extraction was done by one of the authors (A.v.M) and a systemic analysis was applied that is normally used for meta-analysis[11]. From all reports author name, year of publication, number of patients, intervention and outcome data were noted.

Results

From 2000 until 2013 a total of 31 phase I, II or retrospective clinical trials were reported that enrolled 1 or more CS patients: 11 phase I, 11 phase II and 8 retrospective studies. Figure 1 shows a flow-chart indicating the search method for clinical trials included in this analysis. Figure 2 shows a timetable with the number and type of clinical trials that met our criteria and their time of publication showing an increasing number of publications from 2004 onwards. The data from the trials that were included in this study are shown in Table 1 for the phase I trials, Table 2 for phase II trials and Table 3 for the results of the retrospective studies. In the clinical trials that were identified a total of 1927 patients were included of which 855 are patients with CS. Histological subtypes included were conventional, dedifferentiated and mesenchymal. The actual number of patients with CS may be higher because in some of the phase I trials only the CS patients who had an objective response or stable disease were reported but more may have been enrolled. The drugs that were being tested were mostly non-cytotoxic in the phase I trials, either alone or in combination with another non-cytotoxic agent or conventional chemotherapy in the phase II trials. For the retrospective studies all treatments were conventional chemotherapy based. In the phase I trials of the 13 included CS patients there were no complete response (CR), 2 (15%) partial response (PR) and 7 (54%) stable disease (SD). For the phase II trials 156 CS patients were enrolled with 2 (1.3%) CR, 2 (1.3%) PR and 21 (13.4%) SD. The results on the clinicaltrials.gov website for current trials are shown in Table 4. Two phase I trials, one phase IB/II trial and three phase II trials were found. There are no phase III trials that are currently or were ever recruiting CS patients.

Discussion

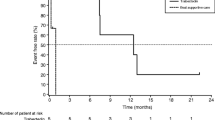

CS is a primary bone cancer that in most patients can be cured by local treatment alone. When tumors are unresectable, either because of locally advanced or metastatic disease, systemic treatment options are very limited due to the current view that non-surgical treatment options have no benefit. Currently for advanced CS patients the outcome is poor with an overall survival of less than two years[5, 40, 41].

The general insensitivity to chemotherapy in CS may be due to activation of anti-apoptotic and pro-survival pathways and therefore future treatment of advanced CS patients could benefit from targeted agents that specifically interfere with these pathways, rendering the tumours more sensitive to the conventional chemotherapeutic agents[8, 9, 40]. For instance, the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL are highly expressed in all CS subtypes and the BH-3 mimetic ABT-737 renders CS cell lines sensitive to the conventional chemotherapeutic agents doxorubicin and cisplatin[10, 40]. Survivin, a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein family, is expressed in CS samples and RNA interference targeted on survivin results in cell cycle arrest and increased apoptotic rates in CS cell lines[42]. However, despite promising results in vitro, some novel approaches never make it to a clinical trial. An example of this is the combination treatment of the Bcl-2 inhibitor ABT-737 and doxorubicin. Drug companies were not interested to supply drug for a clinical trial so it remains unclear if this combination is beneficial to patient outcome.

Two recent retrospective studies as well as animal studies suggested that a subgroup of the patients may benefit from non-cytotoxic agents, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or a combination[6, 7, 41]. In systemic treatment, being either a doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy regimen or non-cytotoxic drugs as imatinib and sirolimus, significantly improved survival compared to no treatment in central CS patients with unresectable disease was shown[41]. For patients with only locally advanced disease radiotherapy may be a good therapeutic option with a significant survival benefit compared to no treatment. Patients with mesenchymal or dedifferentiated CS may also benefit from systemic treatment[6], and further clinical studies are warranted looking at specific CS subtypes.

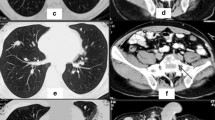

Recently also new treatment options were tested in clinical trials such as the hedgehog (Hh) inhibitor IPI-926. Hedgehog signaling was previously shown to be important in CS genesis[43–45]. CS xenograft models were treated with IPI-926 and showed a downregulation of the Hh pathway in the tumors and a significant growth inhibition in both newly planted as well as established CS tumours with a mean of 43%[30]. Because of the strong preclinical results a randomized phase II trial studying the effect of IPI-926 compared to placebo in metastatic or locally advanced CS patients was conducted (NCT01310816). The study showed that IPI-926 is well tolerated but there was no difference in PFS or OS compared to placebo. However a small subset of patients had minor reductions in tumour size. Another Hh inhibitor that was tested in a phase II trial including advanced CS patients was GDC-0449, also called vismodegib (NCT01267955). This study did not meet its primary endpoint, but the results suggested activity of the drug in a subset of patients with progressive grade 1 or 2 conventional CS[46]. Despite the fact that in both studies only a small subset showed benefit, it is important to do these trials even if the results do not seem promising for the whole patient group. By studying the tumor tissue of the small subset of responders, we may learn to better understand the mode of action. Moreover, this will enable the identification of biomarkers to predict which patients do respond to the treatment to improve patient selection in future trials.

According to the clinicaltrials.gov website currently 6 clinical phase I or II trials are enrolling CS patients, in all of these trials non-cytotoxic agents are being tested either alone or in combination. These treatments are based on preclinical work that has been conducted over the last years and which shows promising results. An example of this is the mTOR pathway. Dysregulation of mTOR signaling can be found in many tumor types, however in clinical trials inhibitors of mTOR so far show only modest results, which may be due to activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. In CS, both mTOR and AKT were shown to be activated[28, 42]. Dual inhibition using BEZ235 dramatically decreased growth of CS cell lines and xenografts[28]. The euroSARC consortium, http://www.eurosarc.eu, is starting a phase II study in unresectable conventional, dedifferentiated and mesenchymal CS with the combination of sirolimus and cyclofosfamide. An exploratory analysis of the mTOR pathway is foreseen in this study with pharmacokinetic assays on tumour biopsies taken before and after treatment (http://www.eurosarc.eu).

We conducted a search for all clinical phase I or II trials and retrospective studies that included CS patients. Because we intended to include modern imaging and study designs the survey was limited to the period from 2000 until 2013. The list of the phase I trials that met our search criteria is probably not completely reflecting the actual number of CS patients enrolled in phase I clinical trials, which is caused by the search strategy by which trials that included CS patients without mentioning them in the abstracts are very difficult to find. Some of the phase I trials could be found by using the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register or the clinicaltrials.gov database, although not all trials are registered in these databases. In the phase I trials, with an average of 34 recruited patients, only a small number of CS patients were enrolled at various dose levels which make it difficult to conclude on the effect of these new treatment options specifically for CS patients. For the phase II trials sarcoma patients were enrolled in different strata. Some strata included CS patients while the studies by Grignani and Italiano were restricted to CS patients only[46, 47].

For the retrospective studies it was difficult to make definite conclusions on the effect of systemic therapy because many different chemotherapy treatment regimens were used in patients with different stages of disease and different CS subtypes. As the biological behavior of the subtypes differs much with therefore expected different outcomes it is hard to conclude from studies where the specific subtype is not reported. The study by Cesari[48] is very interesting because it shows that mesenchymal CS patients who had a complete surgical remission may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy with a 10 year disease free survival that improves from 10% without chemotherapy to 76% with chemotherapy. This is in line with previous studies and the current opinion is that mesenchymal CS is a chemotherapy sensitive tumor and that patients therefore benefit from chemotherapy treatment[25, 29]. For the other CS subtypes it has generally been thought that they are insensitive to conventional chemotherapy, although for dedifferentiated CS activity was shown in individual cases and it is still undefined if chemotherapy treatment is effective[3, 12, 49]. A retrospective study with 337 dedifferentiated CS patients shows that the prognosis remains dismal, however an improvement of survival, not significant, in patients receiving chemotherapy who are under 60 years of age and had limb salvage treatment was found[13]. Also for conventional CS more evidence is currently found that systemic treatment does improve survival[41].

In conclusion, CS is a difficult patient population to study in clinical trials. It is a very rare disease and most patients can be cured by surgery alone, which makes the group of patients that might need adjuvant or palliative treatment even smaller. This is also one of the reasons why it is very difficult to receive funding for these studies. However, from the current poor prognosis of non-resectable locally advanced or metastatic CS patients it is very clear that there is an unmet medical need and new treatment options are warranted. To improve the number of new treatment options for these patients it is essential to collaborate and share data on research so that future clinical trials have a sound biological rationale and can be conducted with as few patients as possible in a short timeframe.

References

Damron TA, Ward WG, Stewart A: Osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing's sarcoma: National Cancer Data Base Report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007, 459: 40-47.

Gelderblom H, Hogendoorn PC, Dijkstra SD, van Rijswijk CS, Krol AD, Taminiau AH, Bovee JV: The clinical approach towards chondrosarcoma. Oncologist. 2008, 13: 320-329.

Angelini A, Guerra G, Mavrogenis AF, Pala E, Picci P, Ruggieri P: Clinical outcome of central conventional chondrosarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2012, 106: 929-937.

Evans HL, Ayala AG, Romsdahl MM: Prognostic factors in chondrosarcoma of bone: a clinicopathologic analysis with emphasis on histologic grading. Cancer. 1977, 40: 818-831.

Italiano A, Mir O, Cioffi A, Palmerini E, Piperno-Neumann S, Perrin C, Chaigneau L, Penel N, Duffaud F, Kurtz JE, Collard O, Bertucci F, Bompas E, Le Cesne A, Maki RG, Ray Coquard I, Blay JY: Advanced chondrosarcomas: role of chemotherapy and survival. Ann Oncol. 2013, 24: 2916-2922.

Perez J, Decouvelaere AV, Pointecouteau T, Pissaloux D, Michot JP, Besse A, Blay JY, Dutor A: Inhibition of chondrosarcoma growth by mTOR inhibitor in an in vivo syngeneic rat model. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e32458-

Bovee JV, Hogendoorn PC, Wunder JS, Alman BA: Cartilage tumours and bone development: molecular pathology and possible therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010, 10: 481-488.

van Oosterwijk JG, Anninga JK, Gelderblom H, Cleton-Jansen AM, Bovee JV: Update on targets and novel treatment options for high-grade osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013, 27: 1021-1048.

van Oosterwijk JG, Meijer D, van Ruler MA, van den Akker BE, Oosting J, Krenacs T, Picci P, Flanagan AM, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Leithner A, Athanasou N, Daugaard S, Hogendoorn PC, Bovee JV: Screening for potential targets for therapy in mesenchymal, clear cell, and dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma reveals Bcl-2 family members and TGFbeta as potential targets. Am J Pathol. 2013, 182: 1347-1356.

Hamada C: The role of meta-analysis in cancer clinical trials. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009, 14: 90-94.

van Oosterwijk JG, Herpers B, Meijer D, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Cleton-Jansen AM, Gelderblom H, van de Water B, Bovee JV: Restoration of chemosensitivity for doxorubicin and cisplatin in chondrosarcoma in vitro: BCL-2 family members cause chemoresistance. Ann Oncol. 2012, 23: 1617-1626.

Serrone L, Zeuli M, Papaldo P, Nardoni C, Pacetti U, Cognetti F: Ifosfamide and epirubicin combination in untreated sarcomas: two treatment schedules. Onkologie. 2001, 24: 465-468.

Schwartz GK, Weitzman A, O'Reilly E, Brail L, de Alwis DP, Cleverly A, Barile-Thiem B, Vinciguerra V, Budman DR: Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of LY293111, an orally bioavailable LTB4 receptor antagonist, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 5365-5373.

Levine AM, Tulpule A, Quinn DI, Gorospe G, Smith DL, Hornor L, Boswell WD, Espina BM, Groshen SG, Masood R, Gill PS: Phase I study of antisense oligonucleotide against vascular endothelial growth factor: decrease in plasma vascular endothelial growth factor with potential clinical efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24: 1712-1719.

Lockhart AC, Bukowski R, Rothenberg ML, Wang KK, Cooper W, Grover J, Appleman L, Mayer PR, Shapiro M, Zhu AX: Phase I trial of oral MAC-321 in subjects with advanced malignant solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007, 60: 203-209.

Chawla SP, Chua VS, Fernandez L, Quon D, Saralou A, Blackwelder WC, Hall FL, Gordon EM: Phase I/II and phase II studies of targeted gene delivery in vivo: intravenous Rexin-G for chemotherapy-resistant sarcoma and osteosarcoma. Mol Ther. 2009, 17: 1651-1657.

Camidge DR, Herbst RS, Gordon MS, Eckhardt SG, Kurzrock R, Durbin B, Ing J, Tohnya TM, Sager J, Ashkenazi A, Bray G, Mendelson D: A phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of the death receptor 5 agonistic antibody PRO95780 in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2010, 16: 1256-1263.

Herbst RS, Eckhardt SG, Kurzrock R, Ebbinghaus S, O'Dwyer PJ, Gordon MS, Novotny W, Goldwasser MA, Tohnya TM, Lum BL, Ashkenazi A, Jubb AM, Mendelson DS: Phase I dose-escalation study of recombinant human Apo2L/TRAIL, a dual proapoptotic receptor agonist, in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 2839-2846.

Olmos D, Postel-Vinay S, Molife LR, Okuno SH, Schuetze SM, Paccagnella ML, Batzel GN, Yin D, Pritchard-Jones K, Judson I, Worden FP, Gualberto A, Scurr M, de Bono JS, Haluska P: Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary activity of the anti-IGF-1R antibody figitumumab (CP-751, 871) in patients with sarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma: a phase 1 expansion cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11: 129-135.

Quek R, Wang Q, Morgan JA, Shapiro GI, Butrynski JE, Ramaiya N, Huftalen T, Jederlinic N, Manola J, Wagner AJ, Demetri GD, George S: Combination mTOR and IGF-1R inhibition: phase I trial of everolimus and figitumumab in patients with advanced sarcomas and other solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17: 871-879.

Stroppa E, Bertuzzi A, Di CG, Mussi C, Lutman RF, Barbato A, Santoro A: Phase I study of non-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in combination with ifosfamide in adult patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcomas. Invest New Drugs. 2010, 28: 834-838.

Pacey S, Wilson RH, Walton M, Eatock MM, Hardcastle A, Zetterlund A, Arkenau HT, Moreno-Farre J, Banerji U, Roels B, Peachey H, Aherne W, de Bono JS, Raynaud F, Workman P, Judson I: A phase I study of the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor alvespimycin (17-DMAG) given intravenously to patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17: 1561-1570.

Merimsky O, Meller I, Flusser G, Kollender Y, Issakov J, Weil-Ben-Arush M, Fenig E, Neuman G, Sapir D, Ariad S, Inbar M: Gemcitabine in soft tissue or bone sarcoma resistant to standard chemotherapy: a phase II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000, 45: 177-181.

Skubitz KM: Phase II trial of pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) in sarcoma. Cancer Invest. 2003, 21: 167-176.

Nooij MA, Whelan J, Bramwell VH, Taminiau AT, Cannon S, Hogendoorn PC, Pringle J, Uscinska BM, Weeden S, Kirkpatrick A, Glabbeke M, Craft AW: Doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in high-grade spindle cell sarcomas of the bone, other than osteosarcoma or malignant fibrous histiocytoma: a European Osteosarcoma Intergroup Study. Eur J Cancer. 2005, 41: 225-230.

Maki RG, D'Adamo DR, Keohan ML, Saulle M, Schuetze SM, Undevia SD, Livingston MB, Cooney MM, Hensley ML, Mita MM, Takimoto CH, Kraft AS, Elias AD, Brockstein B, Blachère NE, Edgar MA, Schwartz LH, Qin LX, Antonescu CR, Schwartz GK: Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 3133-3140.

Pacey S, Ratain MJ, Flaherty KT, Kaye SB, Cupit L, Rowinsky EK, Xia C, O'Dwyer PJ, Judson IR: Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in a subset of patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma from a Phase II randomized discontinuation trial. Invest New Drugs. 2011, 29: 481-488.

Grignani G, Palmerini E, Stacchiotti S, Boglione A, Ferraresi V, Frustaci S, Comandone A, Casali PG, Ferrari S, Aglietta M: A phase 2 trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with recurrent nonresectable chondrosarcomas expressing platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha or -beta: An Italian Sarcoma Group study. Cancer. 2011, 117: 826-831.

Fox E, Patel S, Wathen JK, Schuetze S, Chawla S, Harmon D, Reinke D, Chugh R, Benjamin RS, Helman LJ: Phase II study of sequential gemcitabine followed by docetaxel for recurrent Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, or unresectable or locally recurrent chondrosarcoma: results of Sarcoma Alliance for Research Through Collaboration Study 003. Oncologist. 2012, 17: 321-

Italiano A, Le CA, Bellera C, Piperno-Neumann S, Duffaud F, Penel N, Cassier P, Domont J, Takebe N, Kind M, Coindre JM, Blay JY, Bui B: GDC-0449 in patients with advanced chondrosarcomas: a French Sarcoma Group/US and French National Cancer Institute Single-Arm Phase II Collaborative Study. Ann Oncol. 2013, 24: 2922-2926.

Schuetze SM, Zhao L, Chugh R, Thomas DG, Lucas DR, Metko G, Zalupski MM, Baker LH: Results of a phase II study of sirolimus and cyclophosphamide in patients with advanced sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012, 48: 1347-1353.

Ha HT, Griffith KA, Zalupski MM, Schuetze SM, Thomas DG, Lucas DR, Baker LH, Chugh R: Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with metastatic or locally advanced soft tissue or bone sarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013, 36: 77-82.

Schwartz GK, Tap WD, Qin LX, Livingston MB, Undevia SD, Chmielowski B, Agulnik M, Schuetze SM, Reed DR, Okuno SH, Ludwig JA, Keedy V, Rietschel P, Kraft AS, Adkins D, Van Tine BA, Brockstein B, Yim V, Bitas C, Abdullah A, Antonescu CR, Condy M, Dickson MA, Vasudeva SD, Ho AL, Doyle LA, Chen HX, Maki RG: Cixutumumab and temsirolimus for patients with bone and soft-tissue sarcoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14: 371-382.

Mitchell AD, Ayoub K, Mangham DC, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Tillman RM: Experience in the treatment of dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000, 82: 55-61.

Dickey ID, Rose PS, Fuchs B, Wold LE, Okuno SH, Sim FH, Scully SP: Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma: the role of chemotherapy with updated outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004, 86-A: 2412-2418.

Staals EL, Bacchini P, Bertoni F: Dedifferentiated central chondrosarcoma. Cancer. 2006, 106: 2682-2691.

Grimer RJ, Gosheger G, Taminiau A, Biau D, Matejovsky Z, Kollender Y, San-Julian M, Gherlinzoni F, Ferrari C: Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma: prognostic factors and outcome from a European group. Eur J Cancer. 2007, 43: 2060-2065.

Dantonello TM, Int-Veen C, Leuschner I, Schuck A, Furtwaengler R, Claviez A, Schneider DT, Klingebiel T, Bielack SS, Koscielniak E: Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of soft tissues and bone in children, adolescents, and young adults: experiences of the CWS and COSS study groups. Cancer. 2008, 112: 2424-2431.

Bernstein-Molho R, Kollender Y, Issakov J, Bickels J, Dadia S, Flusser G, Meller I, Sagi-Eisenberg R, Merimsky O: Clinical activity of mTOR inhibition in combination with cyclophosphamide in the treatment of recurrent unresectable chondrosarcomas. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012, 70: 855-860.

van Maldegem AM, Gelderblom H, Palmerini E, Dijkstra SD, Gambarotti M, Ruggieri P, Nout RA, van de Sande MA, Ferarri C, Ferrari S, Bovee JV, Picci P: Outcome of advanced, unresectable conventional central chondrosarcoma. Cancer. 2014, doi:10.1002/cncr.28845. [Epub ahead of print],

Tiet TD, Hopyan S, Nadesan P, Gokgoz N, Poon R, Lin AC, Yan T, Andrulis IL, Alman BA, Wunder JS: Constitutive hedgehog signaling in chondrosarcoma up-regulates tumor cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2006, 168: 321-330.

Zhang YX, van Oosterwijk JG, Sicinska E, Moss S, Remillard SP, van Wezel T, Buhnemann C, Hassan AB, Demitri GD, Bovee JV, Wagner AJ: Functional profiling of receptor tyrosine kinases and downstream signaling in human chondrosarcomas identifies pathways for rational targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013, 19: 3796-3807.

Bovee JV, van den Broek LJ, Cleton-Jansen AM, Hogendoorn PC: Up-regulation of PTHrP and Bcl-2 expression characterizes the progression of osteochondroma towards peripheral chondrosarcoma and is a late event in central chondrosarcoma. Lab Invest. 2000, 80: 1925-1934.

Ng JM, Curran T: The Hedgehog's tale: developing strategies for targeting cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011, 11: 493-501.

Campbell VT, Nadesan P, Ali SA, Wang CY, Whetstone H, Poon R, Wei Q, Keilty J, Proctor J, Wang LW, Apte SS, McGovern K, Alman BA, Wunder JS: Hedgehog Pathway Inhibition in Chondrosarcoma Using the Smoothened Inhibitor IPI-926 Directly Inhibits Sarcoma Cell Growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014, 13: 1259-

Schrage YM, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, de Miranda NF, van Oosterwijk J, Taminiau AH, van Wezel T, Hogendoorn PC, Bovee JV: Kinome profiling of chondrosarcoma reveals SRC-pathway activity and dasatinib as option for treatment. Cancer Res. 2009, 69: 6216-6222.

Cesari M, Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Mercuri M, Palmerini E, Ferrari S: Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. An analysis of patients treated at a single institution. Tumori. 2007, 93: 423-427.

Huvos AG, Rosen G, Dabska M, Marcove RC: Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. A clinicopathologic analysis of 35 patients with emphasis on treatment. Cancer. 1983, 51: 1230-1237.

Yokota K, Sakamoto A, Matsumoto Y, Matsuda S, Harimaya K, Oda Y, Iwamoto Y: Clinical outcome for patients with dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma: a report of 9 cases at a single institute. J Orthop Surg Res. 2012, 7: 38-

Acknowledgement

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 278742 (Eurosarc).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HG conceived the study. AVM collected data. AVM and HG wrote the paper and JB made comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

van Maldegem, A.M., Bovée, J.V. & Gelderblom, H. Comprehensive analysis of published studies involving systemic treatment for chondrosarcoma of bone between 2000 and 2013. Clin Sarcoma Res 4, 11 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-3329-4-11

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-3329-4-11