Abstract

Grasslands sequester and store large amounts of soil carbon, which is primarily controlled by herbivory and precipitation. However, few studies have examined the combined effects of these two factors and quantified how they control carbon cycling in temperate grasslands. The objective of this study was to quantify how grazing intensity affects the magnitudes and patterns of net CO2 exchange in the mixed-grass prairie, the largest native grassland ecosystem in North America. The study was conducted during two contrasting precipitation years (dry vs. wet summer), which allowed investigation of the interaction between precipitation and grazing intensity on the magnitudes and patterns of net CO2 exchange. Our three grazing regimes have been in place for 20 years and consist of light and heavy grazing and ungrazed exclosures. Ecosystem CO2 exchange rates were strongly influenced by changes in summer precipitation. Decreasing summer precipitation reduced ecosystem respiration (RE) by 45%, gross ecosystem production (GEP) by 75%, and net ecosystem exchange (NEE) by 70%. The lightly grazed pastures had the greatest rates of RE, GEP, and NEE during the wet summer; however, NEE did not differ between grazing treatments in the dry summer. These results indicate that grazing intensity and precipitation interact to influence carbon cycling on mixed-grass prairie ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Understanding the factors controlling the exchange of CO2 between the biosphere and the atmosphere and the sequestration of carbon (C) by landscapes has become a central concern for science, policy, and management (Follett et al. 2000; Kaiser 2000; Schulze et al. 2000; Sims et al. 2008; Morgan et al. 2010; Polley et al. 2010). These concerns have emerged because changes in climate, due to anthropogenic increases in atmospheric CO2 concentrations, is altering the fluxes of trace gases and the sequestration of C by terrestrial ecosystems (Amthor et al. 1998; Wofsy and Harriss 2002). Grasslands represent more than 40% of the global landscape, accrue and store large amounts of soil C, and are influenced by precipitation and grazing intensity (Sala et al. 1988; Amthor et al. 1998; Flanagan et al. 2002; Fay et al. 2008). Consequently, it is vital that we develop a better understanding of the patterns and magnitudes of CO2 exchange between grasslands and the atmosphere and how those exchanges may be influenced by grazing regimes and precipitation. In particular, more carbon cycling knowledge is needed for the mixed-grass prairie, especially in the USA, because it is the largest grassland ecosystem in the Great Plains, encompassing 38% of the grassland area in North America (Lauenroth 1979; Ganjegunte et al. 2005; Ingram et al. 2008).

Net CO2 exchange and C sequestration is the net effect of C fixation by plants, heterotrophic and autotrophic respiration, and soil C storage. All of these processes are potentially sensitive to land use such as grazing intensity (Schuman et al. 1999; LeCain et al. 2000; Welker et al. 2004a; Ingram et al. 2008), abiotic factors such as precipitation or temperature (Briggs and Knapp 1995; Chimner and Welker 2005; Bradford et al. 2006; Chimner et al. 2010; Polley et al. 2010), and soil nitrogen (N) processes (Schulze et al. 2000). However, our understanding of how these factors directly and indirectly affect the magnitudes and patterns of CO2 exchange on rangelands is still rudimentary (Kelly et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2002; Hunt et al. 2004) and requires quantification if we are to develop realistic and effective C management options on rangelands (Allen-Diaz 1996; Kaiser 2000; Wofsy and Harriss 2002; Ingram et al. 2008).

Herbivory and precipitation are two of the most important factors that affect the structure and function of grasslands (Knapp et al. 2002; Bradford et al. 2006). Grasslands in the USA were historically grazed by native ungulates (bison), but have been primarily grazed by domestic livestock (mostly cattle) during the past 50 to 150 years (Hart et al. 1988). Livestock densities, however, have not been uniform and thus different intensities of animal use have been imposed on grasslands. Grazing intensity affects a suite of ecological and biogeochemical processes and properties, such as plant community composition (Derner and Hart 2007), soil physical properties (Ganjegunte et al. 2005; Piñeiro et al. 2010), soil C and N contents (Schuman et al. 1999; Welker et al. 2004a; Ingram et al. 2008; Piñeiro et al. 2010), and magnitudes of CO2 exchange (LeCain et al. 2000; Welker et al. 2004a). However, the interaction between various grazing intensities under different precipitation regimes is not fully understood (Svejcar et al. 2008).

Grassland precipitation amounts, patterns, and forms vary from year to year (Fay et al. 2000; Fay et al. 2002; Knapp et al. 2001; Flanagan et al. 2002; Morecroft et al. 2004; Heisler-White et al. 2008; Tagir et al. 2010). Differences in precipitation amounts and patterns between years are especially important because rainfall and associated soil water properties are important controls on C exchange (Flanagan et al. 2002; Harper et al. 2005), and because they determine whether terrestrial ecosystems are annual C sources or sinks to the atmosphere (Schimel et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2010). However, grazing intensity, which alters plant community composition, production, and soil properties, can modify how precipitation influences the magnitude and pattern of grassland C cycling (Schuman et al. 1999; Ingram et al. 2008). The main objective of this project was to quantify how grazing intensity affects the magnitudes and patterns of net CO2 exchange and its constituents (gross ecosystem production and ecosystem respiration) in a mixed-grass prairie. However, the study was conducted during two contrasting precipitation years (dry vs. wet summer), which allows us to investigate the interaction between precipitation and grazing intensity on the magnitudes and patterns of net CO2 exchange. This study was conducted as part of an interdisciplinary project that addressed multiple facets of C cycling in the mixed-grass prairie (Ganjegunte et al. 2005; Ingram et al. 2008).

Methods

Study areas

Our study was conducted at the USDA-ARS High Plains Grasslands Research Station (HPGRS), west of Cheyenne, Wyoming, located at the southern end of the mixed-grass prairie of North America (41°N, 104°W) (Schuman et al. 1999; LeCain et al. 2000). The elevation at the HPGRS averages 1,930 m with a mean annual precipitation of 380 mm and an average of 127 frost-free days. The average summer temperature is 18°C and the average winter temperature is -2.5°C. The major cool-season (C3) grasses on the site are western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii (Rydb) A. Love) and needle-and-thread grass (Hesperostipa comata (Trin. & Rupr.) Barkworth ssp. comata). The dominant warm-season (C4) grass is blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis (H.B.K.)). The soils are mixed, mesic, Aridic Argiustolls, with the soil series being an Ascalon sandy loam (Schuman et al. 1999). Our studies were limited to the Ascalon soil type, which is representative of more than 50% of the soils in the mixed-grass prairie.

Three grazing treatments have been in place at the site since 1982 and consist of a light stocking rate (21.6 steer-days ha-1), heavy stocking rate (62.7 steer-days ha-1) and no grazing (Schuman et al. 1999; LeCain et al. 2000). The heavy and light grazing treatments consisted of continuous season-long (early June to mid-October) grazing by livestock. The light grazing and heavy grazing treatments each occurred in two replicate pastures that are about 50 ha each with gently rolling terrain. Each lightly grazed pasture has a representative ungrazed exclosure (0.5 ha). Before the initiation of grazing treatments, the site had not been grazed by livestock for 40 years.

Carbon dioxide exchange measurements

Carbon dioxide exchange patterns were quantified by taking measurements during the growing (snow free) seasons from May 2002 to December of 2003. CO2 exchange rates were determined with an infrared gas analyzer (Licor, LI-6200, Lincoln, NE, USA) connected to a clear chamber (50 × 50 × 40 cm) with several small fans continuously mixing air in the chamber during measurements (Vourlitis et al. 1993; Chimner et al. 2010), which was placed over pre-selected plots at the time of each measurement. All chamber measurements (5 plots per pasture/exclosure for a total of 30 plots) were conducted in the three grazing treatments on the same days to minimize differences between days. Soil temperatures at 5 cm were also measured with a standard soil thermometer at the beginning of each measurement. Diel measurements were conducted throughout the day (it took about 2 h to complete one round of gas sampling), starting at predawn and ending at nightfall, roughly every 4 to 6 h. Sampling occurred about every 1 to 4 weeks during the snow-free season. Flux rates were calculated by measuring the change in CO2 concentrations within the chamber (Vourlitis et al. 1993). After placement of the chamber, no measurements were taken until a steady mixing occurred and CO2 concentration in the chamber started increasing or decreasing at a constant rate (typically 20 to 30 s). After steady mixing occurred, measurement of net ecosystem exchange (NEE) commenced and lasted for about 1 to 2 min. The rapid measurements minimized temperature and water vapor increases in the chamber (Vourlitis et al. 1993). The chamber was briefly opened to ambient air (20 to 30 s) after the NEE measurement and then replaced and covered with an opaque cloth to prevent photosynthesis, allowed to mix, and measurements of ecosystem respiration (RE) commenced (Chimner et al. 2010). Gross ecosystem production (GEP) was then subsequently calculated by subtracting the RE rates from the NEE rates. Since we measured ecosystem flux over 24-h periods, we were able to calculate a daily value by lineally interpolating between the time periods.

Plant biomass and physiological ecology

Total plant biomass was harvested on 3 July 2003 from five plots (20 × 50 cm) from each pasture and pooled by treatment. All vegetation in each quadrat was harvested to the soil surface and separated into grass and forb components. Green leaves were separated from dead leaves and stems, all vegetation was oven-dried at 60°C for 48 h, and total biomass was measured to the nearest 0.1 g.

Leaf Area Index (LAI) was measured on 3 July 2003 with a SunScan Canopy Analysis System (Dynamax, Houston, TX, USA) that measures the direct and diffuse components of light simultaneously above and within the canopy to calculate LAI. Twenty random measurements were taken during the late morning/early afternoon in each replicated treatment for a total of 120 measurements. There were no clouds in the sky and no significant differences in incident light between samples. Treatments were pooled for analysis.

Statistical analysis

A repeated-measures, split-plot analysis of variance was conducted using PROC MIXED to test for experimental differences in ecosystem CO2 exchange rates (SAS Institute, Inc. 2009). Replicate chamber measurements were averaged by plot for each year of analysis. Analysis was conducted by year, using pasture × grazing intensity interactions as the random effects, grazing intensity, pasture, year and all possible interactions were treated as fixed effects, and date as a repeated measure. We used compound symmetry structure for repeated-measures analysis as determined by looking at the fit statistics and the Kenward and Roger's correction for degrees of freedom (Littell et al. 2006). An analysis of variance was also conducted for LAI and plant biomass using PROC MIXED (SAS Institute, Inc. 2009). Differences between all treatments were conducted using Tukey's post hoc test with differences at P < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Canopy characteristics

The ungrazed treatment had significantly greater LAI compared to the heavily grazed treatment, but no significant differences were observed in live or dead forbs, litter, or miscellaneous biomass among treatments (Table 1). There was, however, greater mass of live and dead grass in the ungrazed plots compared to the heavily grazed plots. The heavily grazed plots had significantly (P < 0.05) greater lichen biomass compared to the ungrazed plots. Total plant mass did not differ between grazing treatments during 2003.

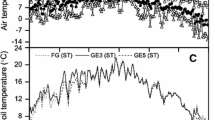

Soil temperatures were also slightly modified by grazing intensity (Figure 1). Soil temperature differences were most pronounced in the daytime hours with heavy grazing, light grazing, and the ungrazed pastures averaging 23.6°C, 22.4°C, 21.1°C over the 2 years, respectively.

Ecosystem carbon cycling

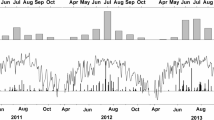

Grazing intensity, pasture, and year were significant factors in the ANOVA for ecosystem C cycling (Table 2). The most significant factor affecting NEE, GEP, and RE was year (Table 2). Total precipitation amounts varied between 2002 and 2003 with a total of 243 and 322 mm, respectively (Figure 2). Total precipitation in 2002 was the ninth lowest in 71 years of record, while 2003 was close to average. The driest part of 2002 was in the spring and early summer (Figure 3). Total precipitation for April, May, and June combined was the fifth driest (69 mm), while the same period in 2003 was above average (152 mm). Although early 2002 was very dry, average precipitation in July, August, and September was near average. Conversely, early 2003 was very wet, but July and August were below average.

The large differences in summer precipitation greatly influenced NEE, GEP, and RE (Figure 4). Daily values of NEE were below zero for the entire summer of 2002. The dry conditions in 2002 also suppressed both GEP and RE. Maximum GEP values were just above 1 g C m-2 day-1 during early 2002 and decreased as the summer progressed and soils further dried out. RE also tracked soil moisture as the highest rates occurred in May and declined during the rest of the summer, with a subsequent increase in September.

Rates of NEE in 2003 varied greatly from both 2002 and from early to late summer 2003 (Figure 4). NEE values peaked at 2.5 g C m-2 day-1 during mid-June, in 2003 and then declined to -3 g C m-2 day-1 during early August. GEP peaked in mid-June (6 g C m-2 day-1) in 2003 and then declined steadily throughout the remainder of the summer to near zero. However, GEP increased in the fall of 2003 up to 2 g C m-2 day-1. RE was most negative in mid-June 2003, reaching values to -6 g C m-2 day-1. RE also declined through the summer except for a high reading on July 30, which occurred immediately after a precipitation event.

Diel patterns of NEE changed between and within years due to precipitation (Figure 5). On 30 May in 2002 and 2003, NEE was positive by early morning and remained positive throughout the daylight period. On 24 June 2002 NEE was positive only during the early morning measurement with negative values of NEE during the rest of the day. NEE was positive most of the day on 24 June 2003. On 15 July, 2002, extremely dry conditions resulted in negative NEE the entire day with the most negative values during mid-day. Although conditions in 2003 were not as dry as 2002, NEE was only positive during the early morning period and was negative the rest of the day. Diel patterns of GEP and RE are not shown, but generally mirrored NEE patterns.

Across the 2 years of measurements, grazing intensity significantly influenced NEE (P = 0.03) and RE (P = 0.02), but not GEP (P = 0.18; Table 2). The grazing intensity × pasture and grazing intensity × year interactions were also significant for NEE, RE, and GEP. The pasture treatment was also significant for NEE and GEP. The two ungrazed enclosures had significantly different NEE (P < 0.01) and GEP (P = 0.03) rates (data not shown). The two lightly grazed pastures also had significantly different NEE (P < 0.01) and GEP (P < 0.01) rates. However, there were no significant differences between the two heavily grazed pastures.

Average carbon fluxes underscored the large interannual differences in our study (Figure 6). Average NEE was negative (losing carbon) for all three grazing treatments in 2002, but was positive in 2003. This was due in a large part to increases in GEP during 2003. In 2003, the lightly grazed treatment was significantly greater than both the ungrazed and heavy grazing treatments for RE and GEP, while NEE was significantly greater compared to the ungrazed treatments.

Discussion

Timing and amount of precipitation had a strong influence on ecosystem carbon fluxes. Decreasing summer precipitation reduced RE by 45%, GEP by 75%, and NEE by 70%. This reduction in 2002 was primarily due to a very dry spring and early summer that inhibited plant growth. There were no summer air temperature differences between the 2 years as they both averaged 10.5°C in 2002 and 2003.

This result is not unexpected as water is a major limiting factor in grasslands (e.g., Knapp et. al 2001; Epstein et al. 2002; Köchy and Wilson 2004; Henry et al. 2006; Polley et al. 2010). Precipitation influences NEE by controlling rates of both GEP and RE (Flanagan et al. 2002; Harper et al. 2005; Bachman et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2010). Dry conditions reduce plant production by forcing plants to regulate their stomata, reducing photosynthetic uptake (Grant and Flanagan 2007) and thus GEP, as we observed in 2002 Bachman et al. (2009) also showed reductions in GEP with soil drying (intraseasonal) during an adjoining experiment on the HPGRS. However, it is not clear whether their elevated CO2 conditions ameliorated this reduction in GEP because the elevated CO2 treatment was combined with frequent watering, thus the sole effect of elevated CO2 on GEP was not measured or reported. Lowered microbial decomposition of organic matter has also been found to reduce RE in dry conditions (Milchunas et al. 1994; Knapp et al. 2001; Harper et al. 2005; Zhou et al. 2008). Under more favorable soil water conditions where GEP increases, a concomitant increase in RE occurs likely due to greater plant and soil respiration associated with greater root exudation and C substrate availability to microbes (Holland et al. 1996).

Carbon cycling in grasslands has been found to respond not only to total precipitation (Lauenroth and Sala 1992; Milchunas et al. 1994; Bradford et al. 2006), but also to the frequency and timing of precipitation (Fay et al. 2000; Flanagan et al. 2002; Knapp et al. 2002; Nippert et al. 2006; Bachman et al. 2009; Chimner et al. 2010; Wiles et al. 2011). For instance, Flanagan et al. (2002) found that mixed-grass prairie rapidly became a net C sink with higher rates of GEP when the spring was wet, compared to normal or dry precipitation years. Similar to the findings in this study, plant production and NEE have been found to be controlled by spring precipitation rates across Northern Great Plains (Zhang et al. 2011; Wiles et al. 2011). Greater spring precipitation was found to increase plant production more than RE, increasing carbon storage. When precipitation is reduced or there are greater intervals between precipitation events, GEP is reduced more than RE and carbon is lost (Zhang et al. 2010). Late summer dry periods, such as seen in 2003, seem to be less important for carbon storage than early season dry periods. However, not all species or grassland ecosystems respond the same to changes in precipitation (Morecroft et al. 2004; Köchy and Wilson 2004; Nippert and Knapp 2007). Recently, Polley et al. (2010) have termed these responses as being functional changes in NEE as they represent a shift in the cascading mechanisms of C cycling-precipitation regimes altering canopy conditions (leaf area, biomass) which in turn controls ecosystem scale C fixation and or C efflux. These functional differences may or may not be accompanied by differences in ecosystem C cycling associated with changes in leaf N, and thus inherent photosynthetic capacity per unit leaf area (Flanagan et al. 2002).

Grazing treatments exhibited only minor differences in overall ecosystem carbon flux rates compared to precipitation effects during our study period. This agrees with other studies that have found that water availability is more important than grazing intensity in grassland carbon cycling (e.g., Risch and Frank 2006). However, we did find interactive effects of grazing intensity × pastures and years on ecosystem carbon fluxes. During the dry summer of 2002, the ungrazed grasslands had greater RE compared to the heavily grazed treatment. However, in the wetter summer of 2003, the lightly grazed pastures had greater RE, GEP, and NEE rates. Our results are similar to those of LeCain et al. (2000) who found that the lightly grazed areas tended to have greater CO2 exchange rates in wetter than drier years . Milchunas et al. (1994) found that during dry years, net primary production decreased more in heavily grazed compared to lightly grazed grasslands, but in wet years, lightly grazed grasslands had higher rates of net primary production than heavily grazed pastures.

One of the key aspects of studying ecosystem responses to either environmental changes (i.e., warming or changes in precipitation) or differences in land use (i.e., grazing regimes) is whether there are initial, transitory, and/or regime shifts to new stable states (Briske et al. 2006). We propose that the lightly grazed system has begun to reach a C cycling equilibrium as the soil C pools have not changed significantly since the soil C pool analysis of these pastures in 1993 (Schuman et al. 1999; Ingram et al. 2008). To the contrary, the ungrazed and the heavily grazed systems continue to show soil C loss (Ingram et al. 2008). These differences in soil C sequestration trajectories are similar to those reported by Welker et al. (2004a) whereby grazing regimes in an alpine grassland of Wyoming are dictating soil C sequestration though intraannual variation in weather may dictate oscillations in the magnitudes of GEP, RE, and NEE.

Interestingly, we found a strong pasture effect in the lightly grazed treatments, including the ungrazed exclosures, which are located within the lightly grazed pastures. We did not find a difference between the heavily grazed pastures. This suggests that our two heavily grazed pastures were more similar than our lightly grazed pastures due possibly to higher stocking densities and more uniform vegetation removal or to original soil properties, initial vegetation composition or slope and aspect which can affect inherent soil water properties.

One of the greatest challenges in grassland carbon biogeochemical studies is linking shorter-term C exchange measurements with integrative C measurements such as soil C pools and traits (Welker et al. 2004b; 2005). Because soil C processes integrate across interannual variation in weather and reflect the net effect of decadal processes of C gain by plants, C loss by respiration, and C transformations in the soil into labile and recalcitrant forms. For instance, Ingram et al. (2008) found that in these same experimental plots that lightly grazed pastures had 13.8 Mg ha-1, heavily grazed pastures had 10.9 Mg ha-1 and the ungrazed treatment had 10.8 Mg ha-1 SOC. The higher rates of GPP in the lightly grazed treatments in conjunction with the higher rates of NEE if maintained year after year, regardless of precipitation regimes would lead to these higher soil carbon pools. The larger soil C pools were also associated with higher total soil N with 1.22 Mg ha-1, 0.94 Mg ha-1, and 0.94 Mg ha-1 N under lightly grazed, heavily grazed and ungrazed treatments, respectively.

Conclusions

Our study found that ecosystem CO2 exchange rates were strongly influenced by changes in summer precipitation. Decreasing summer precipitation reduced RE by 45%, GEP by 75%, and NEE by 70%. The lightly grazed pastures had the greatest rates of RE, GEP, and NEE during the normal precipitation year; however, NEE did not differ between grazing treatments in the dry year. These results indicate that grazing intensity and precipitation interact to influence carbon cycling on mixed-grass prairie ecosystems.

References

Allen-Diaz B: Rangelands in a changing climate: Impacts, adaptations and mitigation. In Climate change 1995. Impacts, adaptations and mitigation of climate change: Scientific-technical analyses. Edited by: Watson RT, Zinyowera MC, Moss RH, Dokken DJ. England: Cambridge Press; 1996:131–158.

Amthor JS, Members of the Ecosystems Working Group: Terrestrial ecosystem responses to global change: A research strategy. ORNL Technical Memorandum 1998/27, 37. Oak Ridge, Tennessee: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; 1998.

Bachman S, Heisler-White JL, Pendall E, Williams DG, Morgan JA, Newcomb J: Elevated carbon dioxide alters impacts of precipitation pulses on ecosystem photosynthesis and respiration in a semi-arid grassland. Oecologia 2009, 162: 791–802.

Bradford JB, Lauenroth WK, Burke IC, Paruelo JM: The influence of climate, soils, weather, and land use on primary production and biomass seasonality in the US Great Plains. Ecosystems 2006, 9: 934–950. 10.1007/s10021-004-0164-1

Briggs JM, Knapp AK: Interannual variability in primary production in tallgrass prairie: Climate, soil moisture, topographic position, and fire as determinants of aboveground biomass. American Journal of Botany 1995, 82: 1024–1030. 10.2307/2446232

Briske DD, Fuhlendorf SD, Smeins FE: A unified framework for assessment and application of ecological thresholds. Rangeland Ecology and Management 2006, 59: 225–236. 10.2111/05-115R.1

Chimner RA, Welker JM: Ecosystem respiration responses to changes in climate in the mixedgrass prairie. Biogeochemistry 2005, 73: 257–270. 10.1007/s10533-004-1989-6

Chimner RA, Welker JM, Morgan J, LeCain D, Reeder J: Experimental manipulations of winter snow and summer rain influence ecosystem carbon cycling in a mixed-grass prairie, Wyoming, USA. Ecohydrology 2010.

Derner JD, Hart RD: Grazing induced modifications to peak standing crop in northern mixed-grass prairie. Rangeland Ecology and Management 2007, 60: 270–276. 10.2111/1551-5028(2007)60[270:GMTPSC]2.0.CO;2

Epstein HE, Burke IC, Lauenroth WK: Regional patterns of decomposition and primary production rates in the U.S. Great Plains Ecology 2002, 83: 320–327.

Fay PA, Carlisle JD, Knapp AK, Blair JM, Collins SL: Altering rainfall timing and quantity in a mesic grassland ecosystem: Design and performance of rainfall manipulation shelters. Ecosystems 2000, 3: 308–319. 10.1007/s100210000028

Fay PA, Kaufman DM, Nippert JB, Carlisle JD, Harper CW: Changes in grassland ecosystem function due to extreme rainfall events: Implications for responses to climate change. Global Change Biology 2008, 14: 1600–1608. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01605.x

Fay PA, Knapp AK, Blair JM, Carlisle JD, Danner BT, McCarron JK: Rainfall timing, soil moisture dynamics, and plant responses in a mesic tallgrass prairie ecosystem. In Changing precipitation regimes and terrestrial ecosystems: A North American perspective. Edited by: Weltzin JF, McPherson GR. Tucson, USA: University of Arizona Press; 2002:147–165.

Flanagan L, Weaver LA, Carlson PJ: Seasonal and interannual variation in carbon dioxide exchange and carbon balance in a northern temperate grassland. Global Change Biology 2002, 8: 599–615. 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2002.00491.x

Follett RF, Kimble JM, Lal R: The potential of U.S. grazing lands to sequester carbon. In The potential of U.S. grazing lands to sequester carbon and mitigate the greenhouse effect. Edited by: Follett RF, Kimble JM, Lal R. Boca Raton, USA: Lewis Publishers; 2000:401–430.

Ganjegunte GK, Vance GF, Preston CM, Schuman GE, Ingram LJ, Stahl PD, Welker JM: Soil organic carbon composition in a northern mixed-grass prairie: Effects of grazing. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2005, 69: 1746–1756. 10.2136/sssaj2005.0020

Grant RF, Flanagan LB: Modeling stomatal and nonstomatal effects on CO 2 fixation in a semiarid grassland. Journal of Geophysical Research 2007, 112: G03011.

Harper CW, Blair JM, Fay PA, Knapp AK, Carlisle JD: Increased rainfall variability and reduced rainfall amount decreases soil CO 2 flux in a grassland ecosystem. Global Change Biology 2005, 11: 322–334. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.00899.x

Hart RH, Samuel MJ, Test PS, Smith MA: Cattle, vegetation, and economic responses to grazing systems and grazing pressure. Journal of Range Management 1988, 41: 282–286. 10.2307/3899379

Heisler-White JL, Knapp AK, Kelly EF: Large precipitation events increase aboveground net primary productivity in semi-arid grasslands. Oecologia 2008, 158: 129–140. 10.1007/s00442-008-1116-9

Henry HAL, Chiariello NR, Vitousek PM, Mooney HA, Field CB: Interactive effects of fire, elevated carbon dioxide, nitrogen deposition, and precipitation on a California annual grassland. Ecosystems 2006, 9: 1066–1075. 10.1007/s10021-005-0077-7

Holland JN, Weixin C, Crossley DAJ: Herbivore-induced changes in plant carbon allocation: Assessment of below-ground C fluxes using carbon-14. Oecologia 1996, 107: 87–94. 10.1007/BF00582238

Hunt ER, Kelly RD, Smith WK, Fahnestock JT, Welker JM, Reiners WA: Carbon sequestration in two rangeland ecosystems from remote sensing and net ecosystem exchange. Environmental Management 2004,33(supplement):S432-S441.

Ingram LJ, Stahl PD, Schuman GE, Buyer JS, Vance GF, Ganjegunte GK, Welker JM, Derner JD: Grazing and Drought Affects on Carbon, Nitrogen and Microbial Communities in a Mixed Grass Prairie. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2008, 72: 939–948. 10.2136/sssaj2007.0038

Kaiser J: Soaking up carbon in forests and fields. Science 2000, 290: 922. 10.1126/science.290.5493.922

Kelly RD, Hunt ER, Reiners WA, Smith WK, Welker JM: Relationships between daytime carbon dioxide uptake and absorbed photosynthetically active radiation for three different mountain/plains ecosystems. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres 2002, 107: 19.1–19.8.

Knapp AK, Briggs JM, Koelliker JK: Frequency and extent of water limitation to primary production in a mesic temperate grassland. Ecosystems 2001, 4: 19–28. 10.1007/s100210000057

Knapp AK, Fay PA, Blair JM, Collins SL, Smith MD, Carlisle JD, Harper CW, Danner BT, Lett MS, Mccarron JK: Rainfall variability, carbon cycling, and plant species diversity in a mesic grassland. Science 2002, 298: 2202–2205. 10.1126/science.1076347

Köchy M, Wilson SD: Semiarid grassland responses to short-term variation in water availability. Plant Ecology 2004, 174: 197–203.

Lauenroth WK: Grassland primary production: North American grasslands in perspective. In Perspectives in grassland ecology. Edited by: French NR. New York: Springer; 1979:3–24.

Lauenroth WK, Sala OE: Long-term forage production of North American shortgrass steppe. Ecological Applications 1992, 2: 397–403. 10.2307/1941874

LeCain DR, Morgan JA, Schuman GE, Reeder JD, Hart RH: Carbon exchange rates in grazed and ungrazed pastures of Wyoming. Journal of Range Management 2000, 53: 199–206. 10.2307/4003283

Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O: SAS for mixed models. Second edition. North Carolina, USA: SAS Institute Inc; 2006.

Milchunas DG, Forwood JR, Lauenroth WK: Productivity of long-term grazing treatments in response to seasonal precipitation. Journal of Range Management 1994, 47: 133–139. 10.2307/4002821

Morecroft MD, Masters GJ, Brown VK, Clarke IP, Taylor ME, Whitehouse AT: Changing precipitation patterns alter plant community dynamics and succession in an arable grassland. Functional Ecology 2004, 18: 648–655. 10.1111/j.0269-8463.2004.00896.x

Morgan JA, Follett RF, Hartwell Allen L Jr, Del Grosso S, Derner JD, Dijkstra F, Franzluebbers A, Fry R, Paustian K, Schoeneberger MM: Carbon sequestration in agricultural lands of the US. 2010. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2010.

Nippert JB, Knapp AK, Briggs JA: Intra-annual rainfall variability and grassland productivity: Can the past predict the future? Plant Ecology 2006, 184: 65–74. 10.1007/s11258-005-9052-9

Nippert JB, Knapp AK: Soil water partitioning as a mechanism for species coexistence in tallgrass prairie. Oikos 2007, 116: 1017–1029. 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15630.x

Piñeiro G, Paruelo JM, Oesterheld M, Jobbágy EG: Pathways of Grazing Effects on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen. Rangeland Ecology and Management 2010,63(1):109–119. 10.2111/08-255.1

Polley HW, Emmerich W, Bradford JA, Sims PL, Johnson DA, Saliendra NZ, Svejcar T, Angell R, Frank AB, Phillips RL, Snyder KA, Morgan JA: Physiological and environmental regulation of interannual variability in CO 2 exchange on rangelands in the western United States. Global Change Biology 2010, 16: 990–1002. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01966.x

Risch AC, Frank DA: Carbon dioxide fluxes in a spatially and temporally heterogeneous temperate grassland. Oecologia 2006, 147: 291–302. 10.1007/s00442-005-0261-7

Sala OE, Parton WJ, Joyce LA, Lauenroth WK: Primary production of the central grassland region of the United States. Ecology 1988, 69: 40–45. 10.2307/1943158

SAS Institute Inc: JMP-IN ver. 9.2. Statistical analysis software. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina; 2009.

Schimel D, Melillo J, Tian H, McGuire AD, Kicklighter D, Kittel T, Rosenbloom N, Running S, Thorton P, Ojima D, Parton W, Kelly R, Sykes M, Neilson R, Rizzo B: Contribution of increasing CO 2 and climate to carbon storage by ecosystems of the United States. Science 2000, 287: 2004–2006. 10.1126/science.287.5460.2004

Schulze E, Wirth C, Heimann M: Managing forests after Kyoto. Science 2000, 289: 2058–2059. 10.1126/science.289.5487.2058

Schuman GE, Reeder JD, Manley JT, Hart RH, Manley WA: Impact of grazing management on the carbon and nitrogen balance of a mixed-grass rangeland. Ecological Applications 1999, 9: 65–71. 10.1890/1051-0761(1999)009[0065:IOGMOT]2.0.CO;2

Sims DA, Rahman AF, Cordova VD, El-Masri BZ, Baldocchi DD, Bolstad PV, Flanagan LB, Goldstein AH, Hollinger DY, Misson L, Monson RK, Oechel WC, Schmid HP, Wofsy SC, Xu L: A new model of gross primary productivity for North American ecosystems based solely on enhanced vegetation index and land surface temperature from MODIS. Remote Sensing of the Environment 2008, 112: 1633–1646. 10.1016/j.rse.2007.08.004

Smith WK, Kelly RD, Welker JM, Fahnestock JT, Reiners WA, Hunt ER: Leaf-to-aircraft measurements of net CO 2 exchange in a sagebrush steppe ecosystem. Journal of Geophysical Research - Atmospheres 2002,108(D3):9.1–9.9.

Svejcar T, Angell R, Bradford JA, Dugas W, Emmerich W, Frank AB, Gilmanov T, Haferkamp M, Johnson DA, Mayeux H, Mielnick P, Morgan J, Saliendra NZ, Schuman GE, Sims PL, Snyder K: Carbon fluxes on North American rangelands. Rangeland Ecology and Management 2008, 61: 465–474. 10.2111/07-108.1

Tagir G, Gilmanov L, Aires Z, et al.: Productivity, Respiration, and Light-Response Parameters of World Grassland and Agroecosystems Derived From Flux-Tower Measurements. Rangeland Ecology and Management 2010, 63: 16–39. 10.2111/REM-D-09-00072.1

Vourlitis GL, Oechel WC, Hastings SJ, Jenkins MA: A system for measuring in situ CO 2 and CH 4 flux in unmanaged ecosystems: An arctic example. Functional Ecology 1993, 7: 369–379. 10.2307/2390217

Welker JM, Fahnestock JT, Povirk K, Bilbrough C, Piper R: Carbon and nitrogen dynamics in a long-term grazed alpine grassland. Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research 2004, 36: 10–19.

Welker JM, Fahnestock JT, Henry G, O'dea K, Chimner RA: CO 2 exchange in the Canadian High Arctic: Response to long-term warming. Global Change Biology 2004, 10: 1981–1995. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00857.x

Welker JM, Fahnestock JT, Sullivan P, Chimner RA: Leaf mineral nutrition of arctic plants in response to long-term warming and deeper snow in N. Alaska Oikos 2005, 109: 167–177.

Wiles LJ, Dunn G, Printz J, Patton B, Nyren A: Spring precipitation as a predictor for peak standing crop of mixed-grass prairie. Rangeland Ecology and Management 2011, 64: 215–222. 10.2111/REM-D-09-00024.1

Wofsy SC, Harriss RC: The North American Carbon Program (NACP). Report of the NACP Committee of the U.S. Interagency Carbon Cycle Science Program. Washington, DC: US Global Change Research Program; 2002:75.

Zhang L, Wylie BK, Lei J, Gilmanov TG, Tieszen LL: Climate-Driven Interannual Variability in Net Ecosystem Exchange in the Northern Great Plains Grasslands. Rangeland Ecology and Management 2010, 63: 40–50. 10.2111/08-232.1

Zhou X, Weng E, Luo Y: Modeling patterns of nonlinearity in ecosystem responses to temperature, CO 2 , and precipitation changes. Ecological Applications 2008, 18: 453–466. 10.1890/07-0626.1

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lisa Walsh and Derek Esposito for help with fieldwork and ARS personnel for logistical help. This manuscript was also improved by the editing of anonymous reviewers. A National Research Initiative-USDA # 2001-35107-11327 award to JMW supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JW designed the project and helped draft the manuscript. RC participated in its design and coordination of the project, performed the statistical analysis, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Chimner, R.A., Welker, J.M. Influence of grazing and precipitation on ecosystem carbon cycling in a mixed-grass prairie. Pastoralism 1, 20 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-7136-1-20

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-7136-1-20