Abstract

Background

This study examined associations between perceived neighborhood illicit drug selling, peer illicit drug disapproval and illicit drug use among a large nationally representative sample of U.S. high school seniors.

Methods

Data come from Monitoring the Future (2007–2011), an annual cross-sectional survey of U.S. high school seniors. Students reported neighborhood illicit drug selling, friend drug disapproval towards marijuana and cocaine use, and past 12-month and past 30-day illicit drug use (N = 10,050). Multinomial logistic regression models were fit to explain use of 1) just marijuana, 2) one illicit drug other than marijuana, and 3) more than one illicit drug other than marijuana, compared to “no use”.

Results

Report of neighborhood illicit drug selling was associated with lower friend disapproval of marijuana and cocaine; e.g., those who reported seeing neighborhood sales “almost every day” were less likely to report their friends strongly disapproved of marijuana (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.29, 0.49) compared to those who reported never seeing neighborhood drug selling and reported no disapproval. Perception of neighborhood illicit drug selling was also associated with past-year drug use and past-month drug use; e.g., those who reported seeing neighborhood sales “almost every day” were more likely to report 30-day use of more than one illicit drug (AOR = 11.11, 95% CI: 7.47, 16.52) compared to those who reported never seeing neighborhood drug selling and reported no 30-day use of illicit drugs.

Conclusions

Perceived neighborhood drug selling was associated with lower peer disapproval and more illicit drug use among a population-based nationally representative sample of U.S. high school seniors. Policy interventions to reduce “open” (visible) neighborhood drug selling (e.g., problem-oriented policing and modifications to the physical environment such as installing and monitoring surveillance cameras) may reduce illicit drug use and peer disapproval of illicit drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

National estimates show that approximately 45.5% of U.S. high school seniors report using marijuana one or more times during their life, over a third (36.4%) report using in the past 12 months, and almost one-quarter (22.7%) report using marijuana one or more times during the past 30 days[1]. Use of other illicit drugs is less prevalent. For example, 4.5% of U.S. high school seniors report ever using cocaine one or more times during their life, 2.6% report using in the past 12 months, and 1.1% report using cocaine one or more times during the past 30 days[1]. Drug use in adolescence (especially late adolescence) is associated with increased risk for drug use disorders as well as other health and social problems such as school failure and sexually transmitted infections including HIV[2–4].

For decades, drug use research has focused largely on individual (e.g., gender), family (e.g., family support) and peer (e.g., peer groups) factors in explaining illicit drug use; however, unexplained variance exists[5]. A relatively under-explored aspect of risk factors for illicit drug use is one’s neighborhood. Social epidemiology research shows that neighborhood environments can play a significant role in drug use[5, 6]. For example, previous studies have examined associations between neighborhood socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., neighborhood poverty) and illicit drug use[7–14]. In addition, prior research shows that exposure to neighborhood violence and crime is associated with illicit drug use[15–17]. Using and analyzing aggregate measures of neighborhood social disorder (including neighborhood drug selling as a component), some other studies have found a relationship between neighborhood social disorder and illicit drug use behaviors[16, 18–20]. A recent study by Epstein and colleagues (2014) showed that neighborhood-level drug activity and social disorder were associated with heroin and cocaine craving among drug misusers[21].

The use of aggregate measures of neighborhood disorder is described in the sociology and public health literature including studies from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN)[22–26]. Multidimensional measures of social disorder are based on Raudenbush’s ecometric theory, i.e., the reliability of a scale improves as you observe multiple indicators, as opposed to single indicators[27]. In addition, the indicators are often clustered with each other and tend to co-occur. PHDCN measures of social disorder (based on ecometrics) are applied to indicators obtained from systematic social observation. However, when measuring a single individual’s evaluation of neighborhood characteristics (as opposed to using systematic social observation) it is may not be necessary to apply aggregate measures of neighborhood characteristics (e.g. neighborhood disorder)[28]. In addition to neighborhood drug selling, aggregate measures of neighborhood social disorder often include the following other components: individuals drinking alcohol in public, individuals using or being addicted to drugs, unemployed individuals hanging out in the streets, and prostitutes on the street[22, 29].

While informative, the previous research on the role of neighborhood factors and illicit drug use has typically not explicitly and specifically examined neighborhood illicit drug selling, a potentially important factor in illicit drug use on its own. Neighborhood illicit drug selling is a distinctive indicator of neighborhood social disorder that may be amenable to policy. We recognize that composite measures (e.g., of neighborhood social disorder) can be important, but might diminish the importance of any one individual component and might be less transferable to policymakers[30–32] (as studies usually use and analyze aggregate measures of neighborhood social disorder—not stratifying by the myriad social disorder components such as neighborhood drug selling)[16, 18–20]. Further, while previous research on neighborhood factors and illicit drug use has used a variety of methods to categorize neighborhood factors (e.g., survey, geographic information systems [GIS]), additional research is needed to examine perceptions of neighborhood characteristics, which may be more closely linked to health and behavior than objectively measured neighborhood characteristics. It is also important to note that, based on our review of the accumulated literature, most previous research on neighborhood factors in illicit drug use has used non-representative local populations, which limits generalizability. We also note that neighborhood factors might not only influence illicit drug use, but drug-related attitudes. Previous studies have examined demographic (e.g., age) and behavioral (e.g., drug use) correlates of peer drug-related attitudes such as peer illicit drug disapproval[33, 34], however, to our knowledge, studies have not examined the effect of neighborhood characteristics on peer drug-related attitudes and thus represents a critical gap in the literature. Importantly, sociological and psychological theories, such as Social Norms Theory[35] and the Theory of Planned Behavior[36], suggest that neighborhood illicit drug selling could be associated with peer illicit drug disapproval. In addition, disapproval and stigmatization towards illicit drug use has previously been shown to be an important correlate of illicit drug use[37]. Research on how perceived neighborhood drug selling relates to both use and (peer) attitudes towards use would add to the literature as there is a lack of information whether perception of neighborhood drug selling is a risk factor for use. Potential mechanisms linking neighborhood drug selling and drug use could be availability of drugs, perceived normality of use, and perhaps pressure from drug dealers to use drugs. In addition, neighborhood drug selling and concomitant issues (including neighborhood violence) could be stressful and therefore influence drug use. For example, in the context of neighborhood stress, adolescents might use marijuana given its well-established anxiolytic effects.

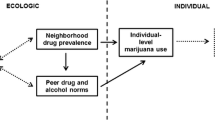

The primary aim of this study is to examine the association of perceived neighborhood illicit drug selling and illicit drug use among a large population-based nationally representative sample of U.S. high school seniors. Because peers (e.g., proportion of school friends using illicit drugs) can influence illicit drug use among adolescents[38, 39], we additionally evaluated the association of perceived neighborhood illicit drug selling and peer illicit drug disapproval among the sample. Based on previous theoretical and empirical research, we hypothesized that perceived neighborhood illicit drug selling would be associated with higher odds for illicit drug use and lower peer illicit drug disapproval among our sample of U.S. high school seniors.

Methods

Data

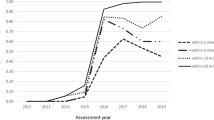

Monitoring the Future (MTF) is an annual cross-sectional survey of high school seniors in approximately 130 public and private schools throughout 48 states in the US[40]. Schools are selected through a multi-stage random sampling procedure: geographic areas are selected, then schools within areas are selected, and finally students within schools are selected. MTF assesses content using six different survey forms, which are distributed randomly. All forms assess demographic characteristics and drug use, however, only survey Form 4 assesses perception of drug selling in one’s neighborhood and friend disapproval towards use of various drugs. To increase power, we combined data from the most recent five cohorts (2007–2011) of data into a single cross-section--consistent with many previous MTF studies[34, 41–48]. MTF protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB). We received IRB approval to examine data on MTF seniors from New York University School of Medicine.

Neighborhood illicit drug selling

Students were asked, “During the past 12 months, how often have you seen people selling illegal drugs in your neighborhood?” Answer options were: 1) “Never”, 2) “A few times a year”, 3) “Once or twice a month”, 4) “At least once a week”, and 5) “Almost every day”. Answers were coded into indicator variables with “never” as the comparison.

Peer illicit drug disapproval

Students were asked about their perception of friend disapproval towards trying various illicit drugs, including marijuana and cocaine. To assess disapproval towards marijuana, students were asked: “How do you think your close friends feel (or would feel) about you trying marijuana (pot, weed) once or twice?” Answer options were: 1) “Don’t disapprove,” 2) “Disapprove” and 3) “Strongly disapprove.” A similar question was asked with regard to use of cocaine. These two variables were coded into indicators: “disapprove” and “strongly disapprove” and “don’t disapprove” served as the comparison.

Past 12-month and past 30-day illicit drug use

MTF asked students about use of various illicit drugs that occurred within the past 12 months and within the past 30 days. Students were asked whether they used marijuana (pot, weed, hashish), and other illicit substances including cocaine, crack, LSD, hallucinogens other than LSD, heroin, MDMA (ecstasy, “Molly”) and nonmedical use of narcotics (other than heroin), tranquilizers (e.g., benzodiazepines), sedatives (e.g., barbiturates) and amphetamine. We then created a new variable with four categories (one for 12 month use and one for 30 day use): 1) no illicit drug use, 2) only marijuana use, 3) use of one illicit drug other than marijuana, and 4) use of more than one illicit drug other than marijuana. We combined use of multiple drugs into one category as an indicator of drug use severity.

Covariates

Students indicated their age (dichotomized by MTF as <18 and ≥18 years), sex (male vs. female), and race/ethnicity (defined by MTF as Black, White and Hispanic). MTF classified population density of students’ residences as non-, small-, or large-metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). Small MSAs are defined as counties or groups of counties with at least one city of 50,000 or more inhabitants and the 24 largest MSAs are defined as large MSAs[40]. The remaining areas are defined as non-MSAs. MTF also assessed level of religious attendance and importance through two ordinal items. We created a mean composite of these two items (range: 1–4) and divided the scores into tertiles representing low (1.0-2.0), moderate (2.5-3.0) and high (3.5-4.0) religiosity. Students were also asked about level of educational attainment of each parent through an ordinal item. We computed a mean score for both parents (or raw score if only one parent) and this was further coded into three groups representing low (1.0-3.0), medium (3.5-4.0), and high (4.5-6.0) education. Students were also asked to indicate the number of evenings they usually go out per week for fun and recreation. We recoded their responses to the ordinal item into: 1) 0–1 evening(s), 2) 2–3 evenings, and 3) 4–7 evenings. These covariates were identified a priori and coding of covariates was based on previous MTF analyses[43, 49–52].

Statistical analyses

Analyses focused on MTF senior students with complete neighborhood illicit drug selling and peer disapproval data (Unweighted N = 10,050; Weighted N = 10,089). Some statistically significant differences between participants with completed neighborhood illicit drug selling and peer disapproval data as compared with the entire sample existed. However, given the large size of the dataset this is not surprising. Because missing data can be common and problematic, we evaluated missingness in the covariates. Since some covariates were missing data (e.g., race/ethnicity [missing 14.3%], religiosity [missing 23.0%]), we allowed for covariates to have missing data in the regression models. In Table 1, we have included the number of missing values for each covariate: The range of missing data for our covariates was 0.3% (age) to 23% (religiosity). These data were missing not at random. We entered missing data indicators to ensure that these cases were not deleted. This method has been used in previous MTF analyses[42, 51–53] to maintain power and representativeness of the sample. Only 47.4% of the analytic sample had case-compete data; therefore, deleting cases with any missing data would have resulted in the listwise deletion of more than half the sample, reducing power and it’s national representativeness.

We examined descriptive statistics (e.g., weighted percentages) for each covariate and then we fit all variables into multinomial multivariable logistic regression models with the four-category drug use variable as the outcome (one model for 12 month use and another model for 30 day use). The comparison variable for both outcome variables was “no use.” These models determined the conditional associations of perceived neighborhood drug selling and peer drug disapproval while controlling for all other covariates. The predictors in the model explain use of 1) just marijuana, 2) one illicit drug other than marijuana, and 3) more than one illicit drug other than marijuana, compared to “no use,” similar to multiple binary logistic regressions. This way each predictor is associated with an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each of the three levels of the outcome variable. We present AORs and CIs for perceived neighborhood drug selling and peer disapproval. Data indicators for cohort (with year 2007 as the comparison) were entered into all models to control for potential cohort effects and/or secular trends. Data were weighted to adjust for differential probability of selection of schools and students. All analyses were design-based for survey data using Taylor series variance estimate (PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC)[54] and conducted using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample of 10,050 U.S. high school seniors. More than half (56.5%) of the sample was ≥18 years old. About half (51.3%) were female and most (62.3%) were White. Almost 62% of students reporting “never” seeing neighborhood drug sales, and 15.7% reporting seeing neighborhood drug sales “a few times per year”. Almost 60% of the sample reported that their friends disapprove of marijuana use, of which 35.5% reported that their friends “strongly disapprove”. On the other hand, 90.2% of the sample reported that their friends disapprove of cocaine use; 72.1% of the sample reported that their friends “strongly disapprove” of cocaine.

The majority of the sample reported no past-year illicit drug use and past-month illicit drug use: 9.9% reported use of more than one illicit drug in the past 12 months, and 4.1% reported use of more than one illicit drug in the past month. The majority of users of illicit drugs other than marijuana also reported used of marijuana (data not presented in table). Specifically, for both 12-month and 30-day users of one illicit drug other than marijuana, all (100%) also reported 12-month/30-day use of marijuana. With regard to use of more than one illicit drug, 66.5% of 12-month users also reported 12-month use of marijuana, and with respect to 30-day use of more than one other illicit drug, 58.3% also reported 30-day use of marijuana.

Neighborhood illicit drug selling and peer illicit drug disapproval

Report of neighborhood illicit drug selling was associated with lower friend disapproval of marijuana and cocaine in multivariable models, controlling for socio-demographic factors/ other covariates (Tables 2 and3). For example, those who reported seeing neighborhood sales “almost every day” were at lower odds of reporting that friends disapproved (AOR = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.47) and strongly disapproved (AOR = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.29, 0.49) of marijuana compared to those who reported never seeing neighborhood drug selling and reported no disapproval (Table 2). Similarly, neighborhood illicit drug selling was associated with lower friend disapproval of cocaine (Table 3). Those who reported seeing neighborhood sales “almost every day” were at lower odds of reporting that their friends disapproved (AOR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.44, 0.77) and strongly disapproved (AOR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.31, 0.52) of cocaine compared to those who reported never seeing neighborhood drug selling and reported no disapproval, for example. In addition, as shown in Tables 2 and3, odds for strong friend disapproval towards use of each drug tended to be more robust (smaller) than non-strong friend disapproval (“disapprove”), when significant. Perceiving drug selling once or more per week (or almost every day) was significantly (negatively) associated with friend cocaine disapproval, but almost all levels of perceived selling in one’s neighborhood were significantly negatively associated with friend marijuana disapproval.

Neighborhood illicit drug selling and illicit drug use

The multivariable associations between neighborhood illicit drug selling and past-year drug use are reported in Table 4, controlling for socio-demographic factors/other covariates and peer disapproval of illicit drugs. Those who reported seeing neighborhood sales “almost every day” were more likely to report 12-month use of marijuana (AOR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.74, 3.09), 12-month use of one illicit drug (AOR = 2.70, 95% CI: 1.88, 3.89), and 12-month use of more than one illicit drug (AOR = 6.19, 95% CI: 4.43, 8.64) compared to those who reported never seeing neighborhood drug selling and reported no 12-month use of illicit drugs. Those who reported seeing neighborhood sales “almost every day” were more likely to report 30-day use of marijuana (AOR = 3.58, 95% CI: 2.74, 4.67), 30-day use of one illicit drug (AOR = 3.91, 95% CI: 2.69, 5.70), and 30-day use of more than one illicit drug (AOR = 11.11, 95% CI: 7.47, 16.52) compared to those who reported never seeing neighborhood drug selling (Table 5). In addition, as shown in Tables4 and5, the effects of reporting neighborhood selling of illicit drugs was stronger for past 30-day use of illicit drugs and strongest for those who used more drugs. With regard to 12-month use, all levels of perceived neighborhood drug selling tended to be associated with higher odds of only marijuana use than use of only one other illicit drug; however, odds tended to be much higher for use of multiple other illicit drugs (Table 4). With respect to 30-day use, the more frequent the witnessing of neighborhood drug selling, the higher the odds for drug use (Table 5). Odds also increased accordingly for use of more illicit drugs other than marijuana (e.g., frequent exposure to selling was associated with increased odds of only marijuana use, even higher odds for other illicit drug use, and much higher odds for use of multiple other illicit drugs in the past 30 days) (Tables 4 and5).

Discussion

Adolescence is an important developmental period for the initiation of illicit drugs[4, 55, 56]. In this study, among a population-based nationally representative sample of U.S. high school seniors, we found that perception of neighborhood illicit drug selling was associated both with illicit drug use and peer disapproval of illicit drugs. Specifically, report of neighborhood illicit drug selling was associated with lower peer disapproval and more illicit drug use. Furthermore, increased frequency of witnessing neighborhood drug-dealing is associated with “more severe” use (e.g., more recent use, use of drugs “harder” than marijuana and multiple illicit drugs). In addition, we found that increased frequency of witnessing drug selling was associated with lower levels of friend disapproval toward use of marijuana and cocaine. Disapproval (self-, peer-, and perceived societal disapproval) has previously been found to be a robust protective factor against drug use[34, 37, 57–60]. These findings suggest that increased frequency of witnessing drug selling in one’s neighborhood is associated with lowered friend disapproval toward marijuana, but much higher frequency of witnessing drug selling was needed in order for students to report significantly lower friend disapproval toward cocaine. Marijuana is the least stigmatized or disapproved illicit drug and cocaine use is more heavily stigmatized[37]. For example, 42.1% of young adults (age 23–26) disapprove of an adult trying marijuana, but 86.0% of young adults disapprove of an adult trying cocaine[61]. While use of a drug is generally associated with decreased disapproval or stigma toward use[34, 37], these findings add to our understanding in that witnessing drug selling in one’s neighborhood is also associated with decreases in friend drug disapproval.

Our study adds to the burgeoning literature on the role of the neighborhood social context on illicit drug use among adolescents. By and large, our findings are consistent with existing studies evaluating the role of neighborhood environments in illicit drug use[16, 18–20]. However, because aggregate measures of neighborhood social disorder include other factors such as alcohol use, drug use, drug addiction, and prostitution, it is unclear whether multiple aspects of neighborhood social disorder are simultaneously needed to detect significant effects on illicit drug use. While multiple aspects of social disorder may contribute to illicit drug use, aggregate measures obscure the importance of any one particular aspect on illicit drug use. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of a neighborhood characteristic on peer drug attitudes and thus our study provides a new contribution to the literature.

There are a variety of potential explanations for our study findings. First, neighborhood characteristics such as neighborhood drug selling may influence social norms, which, in turn, may influence perception of drug use and abuse and ones use and abuse of drugs[37]. Indeed, it is possible that individuals begin to become desensitized to drug use when they frequently witness drug sales. When drug use or drug selling becomes somewhat of a normalized activity in one’s view it thus seems that disapproval towards use decreases, leaving individuals at higher risk for drug use. Second, neighborhood drug selling and concomitant issues (including neighborhood violence) might be also stressful and therefore influence drug use[7, 16, 62, 63]. Third, witnessing drug selling may also be an indicator of drug availability in one’s neighborhood, potentially leading to use and abuse of drugs. For instance, exposure to users and familiarity with users has previously been found to be robust risk factors for drug use[60, 64]. Furthermore, neighborhood drug dealers might pressure purchase of drugs and drug use among adolescents as well as other community members. Students reporting neighborhood drug selling may be more likely to know the drug dealers, notice selling, or even purchase or sell drugs themselves. In addition to confirming findings from our study in other samples, future research should identify mechanisms through which neighborhood drug selling might contribute to increases in illicit drug use among adolescents, including the influence of neighborhood drug selling on social norms. Future studies should also examine temporal associations, which are needed to more carefully examine the direction of association.

Findings from this study may be relevant to practice and policy, including the potential need for neighborhood-level policy changes. Empirical evidence from the criminology and public health literature shows that drug-related crime can be decreased by modifying the social and physical neighborhood environment through a variety of strategies[65–68]. Policies monitoring illicit drugs may reduce the availability of illicit drugs and therefore reduce neighborhood drug selling. For example, local police attention in “hot spots” or areas common for neighborhood drug selling (known as problem-oriented policing) may be a useful strategy for reducing “open” (visible) neighborhood drug selling[65, 66, 68]. In addition, adjustments to the physical environment (e.g., installing and monitoring surveillance cameras and landscaping trees and shrubs) might also prove to be beneficial in reducing open neighborhood drug selling[67, 68]. It should be noted that even in states where marijuana use is decriminalized, sales and use in “public view” are still illegal[69]. Our study demonstrates the role of neighborhood factors in shaping drug use among adolescents, and past evidence showing the effectiveness neighborhood-oriented policing approaches suggests that neighborhood-level policy changes may help reduce illicit drug use among this population.

Limitations

First, we recognize that reverse causality is a possibility: individuals who used illicit drugs may report higher rates of neighborhood drug sales. As these are cross-sectional data, temporal ambiguity is a concern; longitudinal study designs are needed to provide evidence of temporal ordering. Additionally, natural experiments or policy changes (e.g., police efforts targeting neighborhood drug selling) could be evaluated and would provide the strongest evidence for causality. As previously discussed, neighborhood-level factors can be measured in a variety of ways, including objectively via systematic social observation[70]. In this study, only self-reported information on one neighborhood factor (i.e., neighborhood illicit drug selling) was available to us. Therefore, same-source bias (also known as shared-observer bias) might be an issue, as the exposure (perceived neighborhood illicit drug selling) and the outcomes (peer attitudes towards illicit drug and illicit drug use) were all assessed via self-report[71, 72]. Because self-reported drug use information was collected, there might be some misclassification, in part due to social desirability bias. We recognize that we examined perception of one’s residential neighborhood, which is only one neighborhood context. Spatial polygamy asserts that people experience and interact with multiple neighborhood environments, which can influence their health and health behavior including drug use behaviors[73, 74]. Because high school students spend significant amount of time at school[75], their school neighborhood environment may influence drug use behaviors. While we controlled for several confounding factors, residual confounding may also be a concern (e.g., we were unable to control for neighborhood poverty, residential stability and residential selection because these variables where not included in the survey). Finally, missing data (especially 14.3% missing for race/ethnicity and 23.0% missing for religiosity, with data missing not at random) is somewhat problematic. However, to maintain power and representativeness we included missing data indicators for covariates in all analyses.

Conclusion

We found that perceived neighborhood drug selling was associated with lower peer disapproval of illicit drugs and more illicit drug use among a population-based nationally representative sample of U.S. high school seniors. Policy interventions to reduce “open” (visible) neighborhood drug selling (e.g., problem-oriented policing and modifications to the physical environment such as installing and monitoring surveillance cameras) may reduce illicit drug use and peer disapproval of illicit drugs.

References

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE: Monitoring the Future national results on drug use: 1975–2013: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. 2014, Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan

Behrendt S, Wittchen HU, Hofler M, Lieb R, Beesdo K: Transitions from first substance use to substance use disorders in adolescence: is early onset associated with a rapid escalation?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 99: 68-78.

Chen CY, O’Brien MS, Anthony JC: Who becomes cannabis dependent soon after onset of use? Epidemiological evidence from the United States: 2000–2001. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005, 79: 11-22.

Gruber AJ, Pope HG: Marijuana use among adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002, 49: 389-413.

Kwan M-P, Peterson RD, Browning CR, Burrington LA, Calder CA, Krivo LJ: Reconceptualizing Sociogeographic Context for the Study of Drug Use, Abuse, and Addiction. Geography and Drug Addiction. Edited by: Thomas YF, Richardson D, Cheung I. 2008, Berlin: Springer, 437-446.

Galea S, Rudenstine S, Vlahov D: Drug use, misuse, and the urban environment. Drug Alcohol Review. 2005, 24: 127-136.

Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS: Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2001, 42: 151-165.

Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA: A multilevel analysis of neighborhood context and youth alcohol and drug problems. Prev Sci. 2002, 3: 125-133.

Hoffmann JP: The community context of family structure and adolescent drug use. J Marriage Fam. 2002, 64: 314-330.

Ford JM, Beveridge AA: Varieties of substance use and visible drug problems: Individual and neighborhood factors. J Drug Issues. 2006, 36: 377-392.

Sunder PK, Grady JJ, Wu ZH: Neighborhood and individual factors in marijuana and other illicit drug use in a sample of low-income women. Am J Community Psychol. 2007, 40: 167-180.

Buu A, Dipiazza C, Wang J, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA: Parent, family, and neighborhood effects on the development of child substance use and other psychopathology from preschool to the start of adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009, 70: 489-498.

Chauhan P, Widom CS: Childhood maltreatment and illicit drug use in middle adulthood: the role of neighborhood characteristics. Dev Psychopathol. 2012, 24: 723-738.

Molina KM, Alegria M, Chen CN: Neighborhood context and substance use disorders: a comparative analysis of racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 125 (Suppl 1): S35-43.

Duncan DT, Hatzenbuehler ML, Johnson RM: Neighborhood-level LGBT hate crimes and current illicit drug use among sexual minority youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 135: 65-70.

Copeland-Linder N, Lambert SF, Chen YF, Ialongo NS: Contextual stress and health risk behaviors among African American adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40: 158-173.

Lambert SF, Brown TL, Phillips CM, Ialongo NS: The relationship between perceptions of neighborhood characteristics and substance use among urban African American adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. 2004, 34: 205-218.

Latkin CA, Williams CT, Wang J, Curry AD: Neighborhood social disorder as a determinant of drug injection behaviors: a structural equation modeling approach. Health Psychol. 2005, 24: 96-

Latkin CA, Curry AD, Hua W, Davey MA: Direct and indirect associations of neighborhood disorder with drug use and high-risk sexual partners. Am J Prev Med. 2007, 32: S234-S241.

Wright DA, Bobashev G, Folsom R: Understanding the relative influence of neighborhood, family, and youth on adolescent drug use. Subst Use Misuse. 2007, 42: 2159-2171.

Epstein DH, Tyburski M, Craig IM, Phillips KA, Jobes ML, Vahabzadeh M, Mezghanni M, Lin JL, Furr-Holden CD, Preston KL: Real-time tracking of neighborhood surroundings and mood in urban drug misusers: application of a new method to study behavior in its geographical context. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 134: 22-29.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW: Systematic social observation of public spaces: a new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol. 1999, 105: 603-651.

Molnar BE, Gortmaker SL, Bull FC, Buka SL: Unsafe to play? Neighborhood disorder and lack of safety predict reduced physical activity among urban children and adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2004, 18: 378-386.

Molnar BE, Miller MJ, Azrael D, Buka SL: Neighborhood predictors of concealed firearm carrying among children and adolescents: results from the project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods. Archives Pediatrics Adolescent Med. 2004, 158: 657-664.

Thomas JC, Torrone EA, Browning CR: Neighborhood factors affecting rates of sexually transmitted diseases in Chicago. J Urban Health. 2010, 87: 102-112.

Browning CR, Soller B, Gardner M, Brooks-Gunn J: “Feeling Disorder” as a comparative and contingent process: gender, neighborhood conditions, and adolescent mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2013, 54 (3): 296-314.

Raudenbush SW: The Quantitative Assessment of Neighborhood Social Environments. Neighborhoods and Health. 2003, 112-131.

DeVellis RF: Scale development: Theory and Applications. 2012, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 3

Ross CE, Mirowsky J: Disorder and decay the concept and measurement of perceived neighborhood disorder. Urban Aff Rev. 1999, 34: 412-432.

Duncan DT, Aldstadt J, Whalen J, Melly SJ: Validation of Walk Scores and Transit Scores for estimating neighborhood walkability and transit availability: a small-area analysis. GeoJournal. 2013, 78: 407-416.

Duncan DT, Aldstadt J, Whalen J, Melly SJ, Gortmaker SL: Validation of Walk Score® for estimating neighborhood walkability: an analysis of four US metropolitan areas. Int J Environmental Res Public Health. 2011, 8: 4160-4179.

Duncan DT, White K, Aldstadt J, Castro MC, Whalen J, Williams DR: Space, race and poverty: spatial inequalities in walkable neighborhood amenities?. Demogr Res. 2012, 26: 409-448.

Palamar JJ: A pilot study examining perceived rejection and secrecy in relation to illicit drug use and associated stigma. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012, 31: 573-579.

Palamar JJ: Predictors of Disapproval toward “Hard Drug” Use among High School Seniors in the US. Prev Sci. in press. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0436-0

Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD: Perceiving the community norms of alcohol use among students: some research implications for campus alcohol education programming*. Substance Use Misuse. 1986, 21: 961-976.

Ajzen I, Driver BL: Prediction of leisure participation from behavioral, normative, and control beliefs: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Leis Sci. 1991, 13: 185-204.

Palamar JJ, Kiang MV, Halkitis PN: Predictors of stigmatization towards use of various illicit drugs among emerging adults. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2012, 44: 243-251.

Kuntsche E, Jordan MD: Adolescent alcohol and cannabis use in relation to peer and school factors. Results of multilevel analyses. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006, 84: 167-174.

Tucker JS, Pollard MS, De La Haye K, Kennedy DP, Green HD: Neighborhood characteristics and the initiation of marijuana use and binge drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 128: 83-89.

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE: Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug use, 1975–2012: Volume I, Secondary School Student. 2013, Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan

Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Martz ME, Maggs JL, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD: Extreme binge drinking among 12th-grade students in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167: 1019-1025.

Palamar JJ, Ompad DC: Demographic and socioeconomic correlates of powder cocaine and crack use among high school seniors in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014, 40: 37-43.

Palamar JJ, Ompad DC, Petkova E: Correlates of intentions to use cannabis among US high school seniors in the case of cannabis legalization. Int J Drug Policy. 2014, 25: 424-435.

Veliz P, Boyd C, McCabe SE: Adolescent athletic participation and nonmedical adderall use: An exploratory analysis of a performance-enhancing drug. J Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2013, 74: 714-

Veliz PT, Boyd C, McCabe SE: Playing through pain: sports participation and nonmedical use of opioid medications among adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2013, 103: e28-e30.

O’Malley PM, Johnston LD: Driving after drug or alcohol use by US high school seniors, 2001–2011. Am J Public Health. 2013, 103: 2027-2034.

McCabe SE, West BT: Medical and nonmedical use of prescription stimulants: results from a national multicohort study. J Am Academy Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013, 52: 1272-1280.

McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ: Leftover prescription opioids and nonmedical use among high school seniors: a multi-cohort national study. J Adolesc Health. 2013, 52: 480-485.

Wallace JM, Vaughn MG, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE: Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic factors, and smoking among early adolescent girls in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 104: S42-S49.

Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Wallace JM: Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between parental education and substance use among US 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students: findings from the monitoring the future project. J Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2011, 72: 279-

Palamar JJ, Zhou S, Sherman S, Weitzman M: Hookah use among US high school seniors. Pediatrics. 2014, 134: 227-234.

Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD: Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among US high school seniors from 1976 to 2011: Trends, reasons, and situations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 133: 71-79.

Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD: Accessibility over availability: associations between the school food environment and student fruit and green vegetable consumption. Child Obes. 2014, 10: 241-250.

Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA: Applied Survey Data Analysis. 2010, Boca Raton: CRC Press

Latimer W, Zur J: Epidemiologic trends of adolescent use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010, 19: 451-464.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2011 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2014

Bachman JG, O’Malley PMJLF, O’Malley PM: Explaining the recent decline in cocaine use among young adults: further evidence that perceived risks and disapproval lead to reduced drug use. J Health Soc Behav. 1990, 31: 173-184.

Bachman JG, Johnson LD, O’Malley PM: Explaining recent increases in students’ marijuana use: impacts of perceived risks and disapproval, 1976 through 1996. Am J Public Health. 1998, 88: 887-892.

Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG, Li G, Hasin D: Birth cohort effects on adolescent alcohol use: the influence of social norms from 1976 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012, 69: 1304-1313.

Palamar JJ, Halkitis PN, Kiang MV: Perceived public stigma and stigmatization in explaining lifetime illicit drug use among emerging adults. Addiction Res Theory. 2013, 21: 516-525.

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE: Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2012: Volume 2, College students and adults ages 19–50. 2013, Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan

Bujarski SJ, Feldner MT, Lewis SF, Babson KA, Trainor CD, Leen-Feldner E, Badour CL, Bonn-Miller MO: Marijuana use among traumatic event-exposed adolescents: posttraumatic stress symptom frequency predicts coping motivations for use. Addict Behav. 2012, 37: 53-59.

Low NC, Dugas E, O’Loughlin E, Rodriguez D, Contreras G, Chaiton M, O’Loughlin J: Common stressful life events and difficulties are associated with mental health symptoms and substance use in young adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2012, 12: 116-

Palamar JJ, Kiang MV, Halkitis PN: Development and psychometric evaluation of scales that assess stigma associated with illicit drug users. Subst Use Misuse. 2011, 46: 1457-1467.

Braga AA, Bond BJ: Policing crime and disorder hot spots: a randomized controlled trial. Criminology. 2008, 46: 577-607.

Braga AA: The crime prevention value of hot spots policing. Psicothema. 2006, 18: 630-637.

Mair JS, Mair M: Violence prevention and control through environmental modifications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003, 24: 209-225.

Loukaitou-Sideris A, Eck JE: Crime prevention and active living. Am J Health Promot. 2007, 21: 380-389.

Golub A, Johnson BD, Dunlap E: The race/ethnicity disparity in misdemeanor marijuana arrests in new york city*. Criminology Public Policy. 2007, 6: 131-164.

Furr-Holden CD, Smart MJ, Pokorni JL, Ialongo NS, Leaf PJ, Holder HD, Anthony JC: The NIfETy method for environmental assessment of neighborhood-level indicators of violence, alcohol, and other drug exposure. Prev Sci. 2008, 9: 245-255.

Diez Roux AV: Neighborhoods and health: where are we and were do we go from here?. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2007, 55: 13-21.

Lu X, Chen Z, Uji M, Nagata T, Katoh T, Kitamura T: Use of mobile phone text message and personality among Japanese university students. Psychology Behavioral Sci. 2013, 2: 192-195.

Matthews SA: Spatial Polygamy and the Heterogeneity of Place: Studying People and Place Via Egocentric Methods. Communities, Neighborhoods, and Health. 2011, New York: Springer, 35-55.

Duncan DT, Kapadia F, Halkitis PN: Examination of spatial polygamy among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in New York City: the p18 cohort study. Int J Environmental Res Public Health. 2014, 11: 8962-8983.

Larson RW, Richards MH, Sims B, Dworkin J: How urban African American young adolescents spend their time: time budgets for locations, activities, and companionship. Am J Community Psychol. 2001, 29: 565-597.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Shilpa Dutta and Kenneth Pass for their assistance with the preparation of this manuscript. The authors would like to thank the principal investigators of Monitoring the Future (NIDA Grant# R01 DA-01411) (PIs: Johnston, Bachman, O’Malley, and Schulenberg) at The University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, Survey Research Center, and the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research for providing access to these data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors report no competing interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Authors’ contributions

DTD conceived the study, interpreted the results, and drafted the article. JJP assisted with the study design, performed the statistical analysis, and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. JHW interpreted the results and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Duncan, D.T., Palamar, J.J. & Williams, J.H. Perceived neighborhood illicit drug selling, peer illicit drug disapproval and illicit drug use among U.S. high school seniors. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 9, 35 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-9-35

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-9-35