Abstract

A large number of scientists from a wide range of medical and surgical disciplines have reported on the existence and characteristics of the clinical syndrome of pelvic girdle pain during or after pregnancy. This syndrome refers to a musculoskeletal type of persistent pain localised at the anterior and/or posterior aspect of the pelvic ring. The pain may radiate across the hip joint and the thigh bones. The symptoms may begin either during the first trimester of pregnancy, at labour or even during the postpartum period. The physiological processes characterising this clinical entity remain obscure. In this review, the definition and epidemiology, as well as a proposed diagnostic algorithm and treatment options, are presented. Ongoing research is desirable to establish clear management strategies that are based on the pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for the escalation of the syndrome's symptoms to a fraction of the population of pregnant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain localised at the pelvic girdle during and after pregnancy has been identified and recorded as an entity since the 4th century BC by Hippocrates. Contemporary medical research since the early 20th century has attempted to clarify the spectrum of the different pathologies that this clinical syndrome represents [1–3].

Despite extensive clinical interest and an increasing number of related publications during the past two decades (Table 1), there is a lack of consensus regarding the incidence, clinical manifestations, treatment algorithms and final outcome of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPGP). A large part of the inconsistency can be attributed to the multiplicity and overlapping of the utilised terminology and related definitions (Table 1).

The scientific and clinical implications of PPGP require the multidisciplinary interaction of a wide number of health-related specialties, including obstetrics and gynaecology, general medicine, orthopaedic surgery, physiotherapy, rheumatology and clinical psychiatry (Table 1). This important parameter is another strong factor that affects the discrepancy and fragmentation of the reported data between different journals and scientists not directly communicating with each other.

Lately, efforts to establish guidelines and accurate definitions of the manifestations of this clinical syndrome have been ongoing and offer the basis for further international research [4]. Following the publication of the European Guidelines in 2005 [4], the authors of 49 subsequent clinical studies [5–53] incorporated, to a degree, the recommended methodology. In parallel, the patient community in the modern era of widespread interactive communications has launched a number of websites and forums focusing on the problem and seeking advice and guidance [54–57].

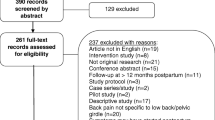

The aim of this minireview article is to present in a comprehensive manner the existing consensus regarding the diagnosis, management and prognosis of PPGP. The PubMed search engine was used to set a query on 20 January 2010 with the keywords "pelvic arthropathy" OR "osteitis pubis" OR "pelvic insufficiency" OR "pelvic pain" OR "pelvic instability" OR "pelvic girdle pain" OR "posterior pelvic pain" OR "low back pain" OR "lumbopelvic pain" OR "symphysis pubis dysfunction" in the title, as well as the term "pregnancy" in any of the search fields of the publications. Whenever additional studies were identified from the references of the retrieved publications, they were also included in this review. In total, 209 studies from 1923 to today are presented in this review according to the terminology that was used by the authors, the decade of publication and the origin of the research (Table 1). Further attention and value were given to those of the 209 studies that represent the highest level of evidence, derived their conclusions from large samples (>30 cases), and took into account contemporary definitions and diagnostic and treatment methodologies. These studies are the ones mostly commented on and presented in this article, as well as in the proposed algorithm of patient management (Figure 1).

Definition

Many terms have been used to describe PPGP syndrome on the basis of causative hypotheses (pelvic joint arthropathy, relaxation, insufficiency, instability), presenting symptoms (pelvic pain, and/or low-back pain, pelvic joint pain) or related topography (posterior pelvic pain, osteitis pubis, symphyseal pelvic dysfunction, low-back pain) (Table 1).

All of these attempts to define the problem have been unsuccessful either because they narrowed the spectrum of this pain syndrome or because they confused its nature by blending it with the syndrome of chronic low-back lumbar pain. There is an existing consensus [58, 59] that pregnancy-related low-back pain is a distinct entity that needs to be excluded before the diagnosis of PPGP is made.

While the responsible pathophysiological mechanisms remain obscure, this clinical syndrome is best defined descriptively by its presentation and topography. With regard to its onset, it has been associated with symptoms beginning between the first trimester, at labour or even during the postpartum period. Thus, terms limiting PPGP to a certain phase pregnancy appear insufficient to cover the whole spectrum of the clinical problem. With regard to this concept, the European Guidelines [60] are based on the musculoskeletal type of the resulting pain (excluding gynaecological and/or urological causative pathologies) localised from the level of the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold over the anterior and posterior elements of the bony pelvis. In 2005, the term pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, or PPGP, was introduced and appears to be the most accurate compared with previous definitions.

Aetiology

The exact mechanisms that lead to the development of PPGP remain uncertain. A variety of approaches have been proposed that suggest hormonal [61–64], biomechanical [65, 66], traumatic [67], metabolic [68], genetic [69] and degenerative [70, 71] etiologic implications.

On the basis of all of these hypotheses, the accumulated evidence advocates in favour of a multifactorial condition during pregnancy and postpartum. The effect of the levels of relaxin and progesterone to the pelvic girdle ligaments is established [72]; however, no consensus of its association with the symptoms of PPGP has been reached [73–75]. This discrepancy can be attributed mostly to methodological differences [76], as well as to the presence of unspecified cofactors altering the clinical presentation. The biomechanical theory and its advocates [15] have highlighted the separation of the pubic symphysis (≥10 mm) as an important threshold. However, this was not proven to be consistent and does not apply to patients with symptoms mostly localised at the posterior pelvic girdle. Moreover, other mechanical theories [77, 78] based on body habitus and lumbar spine stance, as well as foetal size and weight, have also been proven incompatible with all the cases. The role of genetics is still largely unknown, and current knowledge is based on epidemiological indications between first-degree relatives [79–81].

Risk factors

Among a large number of potential factors, those of strenuous work (twisting and bending the back several times per hour), a history of low-back pain, pelvic girdle pain or previous trauma to the bony pelvis were identified [4, 5, 53, 80, 82, 83] as being strongly related to PPGP. Conversely, in the same epidemiologic observational studies, factors such as the time from previous pregnancies, smoking habits, use of contraception, epidural anaesthesia, maternal ethnicity, body mass index, number of previous pregnancies, bone density, foetal weight and age were not linked with increased risk of PPGP development.

Incidence

Among all the relevant studies, the incidence of PPGP ranges from 4% to 76.4% depending on the definition used, the diagnostic means utilised (for example, patient history, pain questionnaires, clinical tests) and the design of the studies (retrospective or prospective).

As reported by Wu et al. [83], on average, doctors' files verify the syndrome in about 20% fewer cases than patients' reports. The apparent geographical variation of reported PPGP incidence and severity, with higher rates in Scandinavian countries [80, 84] and the Netherlands [47, 83], should be attributed to the increased awareness regarding this condition by healthcare providers and the public [76, 85]. However, the reported cases are spread among a wide variety of countries (Table 1) and across all continents, indicating that PPGP is a universal problem.

Using the definition described above and including only prospectively designed studies of large series of patients with objectively verified symptoms, the prevalence of PPGP is between 16% and 25% [4, 80, 83, 86–88]. Over the same large samples of pregnant women, the clinically persistent PPGP from the postpartum stage to 2 years after childbirth has a reported incidence of 5% to 8.5% [83, 86, 88, 89].

Differential diagnosis

The PPGP diagnosis should be considered after the exclusion of painful visceral pathologies of the pelvis (urogenital, gastrointestinal), lower-back pain syndromes (lumbar disc lesion/prolapsed, radiculopathies, spondylolisthesis, rheumatism, sciatica, spinal stenosis or lumbar spine arthritis), bone or soft tissue infections (typical or atypical such as tuberculosis or syphilitic lesions of pubis), urinary tract infections, femoral vein thrombosis, obstetric complications (preterm labour, abruption, round ligament pain, chorioamnionitis), rupture of symphysis pubis, and bone or soft tissue tumours [13, 19, 37, 90, 91].

A thorough medical history, physical examination and appropriate laboratory tests should always be performed to successfully reach the diagnosis of PPGP. Obviously, a multidisciplinary approach and consultation may be needed, as this syndrome expands to a wide field of anatomically related medical specialties [4, 6, 24, 40, 60]. An algorithm of the necessary diagnostic workup is presented in Figure 1.

Presentation, classification and diagnosis

PPGP, as defined previously, has been associated with pain (stabbing, dull, shooting, burning) located at the general area of pelvic girdle, either posteriorly close to the sacroiliac joints and extending to the gluteal area or anteriorly to the vicinity of the symphysis pubis. It may radiate to the groin, perineum or posterior thigh, lacking a typical nerve root distribution. A precise localisation of the pain is often impossible and may also change during the course of the pregnancy [74, 92].

Current classification systems of PPGP are based on pain localisation [86, 92]. They include five subtypes: (1) type 1 or "pelvic girdle syndrome," comprising symptoms of anterior and posterior pelvic girdle, symphysis pubis and bilateral sacroiliac joints; (2) type 2 or "double-sided sacroiliac syndrome," comprising symptoms of the posterior pelvic girdle and bilateral sacroiliac joints; (3) type 3 or "single-sided sacroiliac syndrome," comprising symptoms of the posterior pelvic girdle and unilateral sacroiliac joint; (4) type 4 or "symphysiolysis," comprising symptoms of the anterior pelvic girdle and pubic symphysis; and (5) type 5 or "miscellaneous," comprising inconsistent findings of the pelvic girdle.

The onset of PPGP varies significantly and has been recorded at stages between the end of the first trimester to the first month postdelivery, including the labour stage [76, 78, 93, 94]. It may be insidious or sudden. In general, postpartum pain may be milder than that during pregnancy. A general consensus exists regarding a peak of symptoms closer to the third trimester between the 24th and 36th weeks of pregnancy [76, 94]. In the majority of cases (up to 93%), PPGP settles and spontaneously disappears after the sixth month postpartum. In the rest of the cases, it persists, acquiring a chronic character.

Several authors [4, 50, 83] have recommended that a careful recording of the pain history of the patient suspected of having PPGP contributes significantly to a successful diagnosis. Characteristics such as exacerbations related to a change of position from sitting to standing or during prolonged sitting or standing, during sexual intercourse, and increased intra-abdominal pressure (coughing, sneezing, micturition, defecation) should be explored. On the basis of the medical history, changes and significant difficulties in performing activities of daily living are usually apparent. History combined with the localisation of the pain, with the addition of pain referral maps [95], can differentiate lower-back pain syndromes, sciatica, visceral or vascular origin syndromes from PPGP.

PPGP pain intensity is repeatedly reported [83, 89, 96, 97] to be around 50 to 60 mm of the visual analogue scale (VAS), ranging significantly, however, throughout the duration of the syndrome from bearable to very serious for the 8% of severely disabled women. Wu et al. [53] described a higher correlation of the resultant disability to the increased "fear of movement" and less to the degree of pain itself.

Alteration of gait patterns has also been associated with the syndrome regarding the inability of these patients to cover long distances or a temporary "catching" sensation or clicking on hip flexion, located mostly anteriorly or unilaterally posteriorly. The gait coordination of these patients is distinctly characterised by slower walking velocity, an increase in the amplitude of the horizontal rotation of the pelvis to the thorax and a reduced relative phase between these rotations, which differentiate PPGP patients from those with lower-back pain and healthy pregnant women [50, 53, 98].

Tenderness to deep palpation of the suprapubic and sacroiliac area along the course of the long posterior sacroiliac and sacrotuberous ligaments, as well as a palpable step of the pubic symphysis joint, may be evident. Signs of local inflammation (erythema, oedema, warmth) may exist in a small percentage of the cases [99, 100].

A wide variety of clinical examinations have been evaluated regarding their usefulness in the assessment and differential diagnosis of PPGP. Earlier studies were more focused on deep palpation and radiologic findings, while lately the weight of diagnosis has shifted toward the cumulative results of specific pain provocation tests [4, 6, 101–104]. For the posterior elements of the pelvic girdle and the sacroiliac joints, the most reliable examinations are the posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4/thigh thrust), the Patrick's FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation at the hip), the active straight leg raise (ASLR), the long dorsal ligament and the Gaenslen tests [4, 6, 101–104]. With regard to the pubic symphysis, the diagnosis is based mostly on deep palpation and the modified Trendelenburg test [25, 84, 105].

Because most of these tests have a proven high specificity but lower sensitivity, there appears to be a consensus for the combined use of all of these tests to minimise false-negative results. Leadbetter et al. [25] described a scoring system to guide clinicians in screening the general pregnant patient population. In that system, they included five essential symptoms: pain of the pubic symphysis on walking, while standing on one leg, while climbing stairs, or while turning over in bed, as well as a history of damage to the pelvis or the lumbosacral area.

Laboratory blood tests are usually normal, with a nonspecific mild elevation of the acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) in a number of cases. However, for reasons related to differential diagnosis, most authors report acquiring a complete blood count, biochemistry and urine analysis [75, 106, 107].

Radiological investigations have a more essential role in the evaluation of the PPGP syndrome. Standard anteroposterior, inlet and outlet pelvic films are used to measure the degree of symphyseal separation and to identify cortical sclerosis, spurring or rarefaction. The use of single-limb stance anteroposterior or flamingo views delineates more subtle cases of pubic symphysis separation and appears useful in quantifying the degree of pelvic girdle instability [108]. The detection of a step-off of more than 2 or 7 mm at the standard anteroposterior or flamingo views, respectively, is considered by some authors as a threshold of pelvic instability [109]. However, no direct association of the extent of the separation or of the radiologic irregularities to the severity of PPGP was identified in a number of studies [15, 109–114]. Computed tomography (CT) scanning has also been performed by some authors, mainly for differential diagnosis [115–117]. However, according to the recent recommendations of the European PPGP research group [4], conventional radiography, CT scans and scintigraphy are inadequately supported for their use in rendering a PPGP diagnosis.

These imaging techniques are usually limited to postpartum females because of the hazard of exposing the foetus to ionising radiation. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is suggested during pregnancy, offering additional advantages of increased resolution and its superiority in allowing visualisation of soft tissue and marrow reactions [24, 118–120]. In addition, according the European guidelines, the MRI scan is recommended for the differential diagnosis of PPGP in all its stages [4].

Transvaginal/transperineal ultrasonography has also been advocated for the diagnosis and monitoring of the progress of pubic symphysis PPGP, with the limitation of being a user-dependent examination [42, 111, 113, 121, 122].

Last, guided local anaesthetic injections to the sacroiliac or pubic symphysis joint and the resulting pain relief during previous positive provocation tests offer significant diagnostic specificity, reaching 100%, but reflect only intra-articular pathologies. PPGP related to extra-articular pathologies may be unaffected (that is, strain of the superficial long sacroiliac joint ligament) [103, 123].

Management

Because of the large heterogeneity of the published studies and the inconsistent quality of the reviewed articles (ranging from large, randomised, controlled trials to uncontrolled case series and case reports), no strong comparative evidence regarding the utilised methods of treatment is possible. Management of the PPGP syndrome as reported during the past few decades involves a variety of clinicians and specialities, as well as a combined interdisciplinary approach.

Before labour, the available options for its management are limited by the presence and the potential hazards to the foetus. Also, the majority of symptomatic patients appear to recover gradually after the first few months postdelivery. For these reasons, a proposed algorithm of management should differentiate between pre- and postpartum cases (Figure 2). Bed rest and symptomatic care appear to be the mainstay of PPGP therapy, at least at its initial stages [4, 12, 47, 85, 124, 125]. Water gymnastics [126] and pelvic tilt exercises [58, 127, 128], with avoidance of maladaptive movements [129], as well as acupuncture [130, 131] and physical fitness exercises at early pregnancy [132] have been identified as beneficial on the basis of the level of reported pain and have been associated with a decrease of the sick leave taken by prepartum patients.

Female patient 38 years of age with persistent type 1 [86]peripartum pelvic girdle pain (PPGP) that was resistant to nonoperative means of therapy. The patient underwent triple pelvic joint fusion 2 years after delivery of her second child. (A) Stork views and radiological evidence of pubic symphysis instability. (B) Intraoperative images of bilateral sacroiliac joints after debridement at the time of grafting and of the pubic symphysis after debridement and application of autologous tricortical bone graft. (C) Radiological confirmation (anteroposterior, inlet and outlet views) of healing of all fusion sites 7 months postoperatively. The patient mobilized independently, experienced significant pain relief and returned to work.

Regarding the cases that remain symptomatic postdelivery, it has been shown that treatment based on specific stabilising exercises offers significant advantages over pain management, functional recovery and generalised health-related quality of life and physical status [133, 134]. Individually tailored, supervised physical therapy is reported to be more effective than general back and/or pelvic pain therapies [46, 58, 104].

Pain relief drug therapies have been evaluated extensively in the literature. The reported consensus is that paracetamol, although safe for use in the pregnant population, is considered inadequate on its own for the PPGP levels of pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have a better pain relief effect but are linked to foetal malformations or pregnancy complications [135]. Luckily, the severity of PPGP symptoms also peaks at the end stages of pregnancy, allowing for NSAID use then or mostly postpartum. Opioids are strictly restricted in the prepartum cases, as well as among lactating females [92]. In a few small series [23, 136, 137], the use of epidural analgesia has been reported with good results, delivered either in a single shot or in extended administration during periods of pain exacerbation. In all cases, it should be considered as a temporary method of pain relief until delivery.

The use of guided injections of local anaesthetics with corticosteroids was tested therapeutically in cases of evident arthritis of the pelvic joints [138, 139]. In several studies [16, 140–142], they were used preoperatively to justify surgery for fusion of the painful pelvic joint or triple fusion of all pelvic articulations. The methods of guidance vary between fluoroscopy, CT and MRI scans, offering targeted administration of chemicals to the degenerative joints without specific evidence of the advantages of one chemical over the others.

A limited number of studies have evaluated the efficacy of antenatal back care education and supplemental therapies such as massage [143], local application of heat and/or cold [46], modified back school classes [96, 144], special pillows [145], sacroiliac joint manipulation and mobilisation [146], pelvic belts [110, 147], radiofrequency denervation of the pain receptors of the sacroiliac joints [148] and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [92, 149], with inconclusive or unconvincing results. A generalised recommendation in the experimental use of some of these methods (cushions and pillows, early patient education and general fitness exercise programs, walking aids and/or wheelchairs) was recently suggested [92] on the basis of the potential beneficial psychophysiological effect at least to a subgroup of the PPGP population and the apparent safety of these noninvasive approaches.

The labour of a pregnant woman with established PPGP syndrome appears to be the phase less investigated with regard to its relationship to the persistence of the symptoms postdelivery. However, there appears to be a consensus regarding minimal stress on the pelvic girdle, avoidance of abduction of the hips over the prespinal/epidural anaesthesia comfort arc of the particular patient and minimisation of the duration of the lithotomy position ("all-four" position or lateral positions should be used instead) [150–152]. Caesarean section does not appear to offer any particular advantages to women with established PPGP syndrome, except for those at the worst extreme, whereas the mere positioning for vaginal delivery is impossible [31, 92, 151]. Early induction of labour or elective caesarean section is advocated by a few of the authors [85, 153] in the most severe cases, but these options are still supported by limited evidence.

Pelvic fusion surgery has been evaluated in a number of case series studies [16, 140–142] and in general represents an end-stage procedure following the failure of nonoperative means and the persistence of debilitating symptoms. A number of authors [154, 155] have advocated in favour of a staged approach, with the application of an external fixator as a temporary stabilisation device serving as an indicator of the potential relief of symptoms if mechanical instability is the main causative factor. Most of these cohort studies represent the experience of tertiary referral centres and report on fusion surgery of one or all three of the pelvic girdle joints (Figure 2). According to the European guidelines [4], the surgical option should be offered as part of a comprehensive management protocol and mostly as an end-stage alternative used by specialist surgeons.

Prognosis

The reported outcomes for patients with PPGP appear to be universally good in the vast majority of prepartum cases. The syndrome is described mostly as a self-limiting condition in which symptoms settle in 93% of the patients within the first 3 months postdelivery. By the first year postdelivery, only 1% to 2% of patients report the persistence of pain. These cases are mostly those patients who had very intense symptoms during the pregnancy period. As reported by Albert et al. [88], 79% of those with severe PPGP symptoms are asymptomatic 2 years postdelivery.

Among several related studies [7, 8, 21, 30, 41, 87, 88, 156, 157], certain risk factors for a worse prognosis have been identified. They are based on the patient's history and demographic, psychosocial and socioeconomic characteristics as well as the intensity of PPGP symptoms. A high number of simultaneously positive provocation diagnostic tests, a lower index of mobility, lack of education and/or unskilled work history, multiparity, prolonged duration of labour, age >29 years, higher pain intensity (VAS score >6), onset of pain at early gestation, combined lumbar and pelvic pain in pregnancy and localisation of pain in more than one of the pelvic joints are all included among these adverse prognostic factors. A positive ASLR test and belief in improvements have both been regarded as important independent factors by Vollestad and Stuge in their recent publication [51].

Recurrence of PPGP is commonly reported (41% to 77%), either with a subsequent pregnancy or related to the menstrual cycle [76, 77, 80]. The exact incidence of recurrence, as well as its related risk factors or the role of preventive measures, is unknown. In the majority of the recorded pregnancy relapses of PPGP, the syndrome reappears in a more severe form [84, 85].

Conclusion

Contemporary clinical awareness of the PPGP syndrome appears to be increasing because of increased public awareness and the interaction of scientists from different medical specialties. Recently introduced definitions and proposed guidelines on PPGP diagnosis and management represent significant improvements, setting the basis for future comprehensive research on this multifactorial pain syndrome. Different treatment modalities and disease-specific outcome measures need to be investigated in multicentre, randomised clinical trials following the previous initiative of the Research Directorate of the European Commission [4].

References

Beer E: Periosteitis of symphysis and descending rami of pubes. Int J Med Surg. 1924, 37: 224-225.

Snelling FG: Relaxation of pelvic symphyses during pregnancy and parturition. Am J Obstet. 1870, 2: 561-596.

Legueue MB, Rochet WL: Les cellulites perivesicales et pelviennes apres certaines cystostomies ou prostatectomies sus-pubiennes. J Urol Med Chir. 1923, 15: 1.

Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B: European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008, 17: 794-819. 10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4.

Albert HB, Godskesen M, Korsholm L, Westergaard JG: Risk factors in developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006, 85: 539-544. 10.1080/00016340600578415.

Ando F, Ohashi K: Using the posterior pelvic pain provocation test in pregnant Japanese women. Nurs Health Sci. 2009, 11: 3-9. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00406.x.

Bastiaenen CH, de Bie RA, Wolters PM, Vlaeyen JW, Leffers P, Stelma F, Bastiaanssen JM, Essed GG, van den Brandt PA: Effectiveness of a tailor-made intervention for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle and/or low back pain after delivery: short-term results of a randomized clinical trial [ISRCTN08477490]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006, 7: 19-10.1186/1471-2474-7-19.

Buchner M, Neubauer E, Zahlten-Hinguranage A, Schiltenwolf M: Age as a predicting factor in the therapy outcome of multidisciplinary treatment of patients with chronic low back pain: a prospective longitudinal clinical study in 405 patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2007, 26: 385-392. 10.1007/s10067-006-0368-1.

Cook C, Massa L, Harm-Ernandes I, Segneri R, Adcock J, Kennedy C, Figuers C: Interrater reliability and diagnostic accuracy of pelvic girdle pain classification. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007, 30: 252-258. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.008.

Elden H, Fagevik-Olsen M, Östgaard HC, Stener-Victorin E, Hagberg H: Acupuncture as an adjunct to standard treatment for pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women: randomised double-blinded controlled trial comparing acupuncture with non-penetrating sham acupuncture. BJOG. 2008, 115: 1655-1668. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01904.x.

Elden H, Hagberg H, Olsen MF, Ladfors L, Östgaard HC: Regression of pelvic girdle pain after delivery: follow-up of a randomised single blind controlled trial with different treatment modalities. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008, 87: 201-208. 10.1080/00016340701823959.

Elden H, Östgaard HC, Fagevik-Olsen M, Ladfors L, Hagberg H: Treatments of pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women: adverse effects of standard treatment, acupuncture and stabilising exercises on the pregnancy, mother, delivery and the fetus/neonate. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008, 8: 34-10.1186/1472-6882-8-34.

Fagevik Olsen M, Gutke A, Elden H, Nordenman C, Fabricius L, Gravesen M, Lind A, Kjellby-Wendt G: Self-administered tests as a screening procedure for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2009, 18: 1121-1129. 10.1007/s00586-009-0948-2.

Fredriksen EH, Moland KM, Sundby J: "Listen to your body": a qualitative text analysis of internet discussions related to pregnancy health and pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. Patient Educ Couns. 2008, 73: 294-299. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.002.

Garras DN, Carothers JT, Olson SA: Single-leg-stance (flamingo) radiographs to assess pelvic instability: how much motion is normal?. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008, 90: 2114-2118. 10.2106/JBJS.G.00277.

Giannoudis PV, Psarakis S, Kanakaris NK, Pape HC: Biological enhancement of bone healing with bone morphogenetic protein-7 at the clinical setting of pelvic girdle non-unions. Injury. 2007, 38 (Suppl 4): S43-S48. 10.1016/S0020-1383(08)70008-1.

Granath A, Hellgren M, Gunnarsson R: Lactose intolerance and long-standing pelvic pain after pregnancy: a case control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007, 86: 1273-1276. 10.1080/00016340701259188.

Gutke A, Josefsson A, Oberg B: Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in relation to postpartum depressive symptoms. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007, 32: 1430-1436.

Gutke A, Kjellby-Wendt G, Oberg B: The inter-rater reliability of a standardised classification system for pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain. Man Ther. 2009, 15: 13-18. 10.1016/j.math.2009.05.005.

Gutke A, Östgaard HC, Oberg B: Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in pregnancy: a cohort study of the consequences in terms of health and functioning. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006, 31: E149-E155.

Gutke A, Östgaard HC, Oberg B: Predicting persistent pregnancy-related low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008, 33: E386-E393.

Haugland KS, Rasmussen S, Daltveit AK: Group intervention for women with pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006, 85: 1320-1326. 10.1080/00016340600780458.

Khan M, Mahmood T: Prolonged epidural analgesia for intractable lumbo-sacral pain in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008, 28: 350-351. 10.1080/01443610802048560.

Kunduracioglu B, Yilmaz C, Yorubulut M, Kudas S: Magnetic resonance findings of osteitis pubis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007, 25: 535-539. 10.1002/jmri.20818.

Leadbetter RE, Mawer D, Lindow SW: The development of a scoring system for symphysis pubis dysfunction. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006, 26: 20-23. 10.1080/01443610500363915.

Lund I, Lundeberg T, Lonnberg L, Svensson E: Decrease of pregnant women's pelvic pain after acupuncture: a randomized controlled single-blind study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006, 85: 12-19. 10.1080/00016340500317153.

Mens JM, Damen L, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ: The mechanical effect of a pelvic belt in patients with pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2006, 21: 122-127. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.08.016.

Mogren I: Perceived health, sick leave, psychosocial situation, and sexual life in women with low-back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006, 85: 647-656. 10.1080/00016340600607297.

Mogren I: Perceived health six months after delivery in women who have experienced low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007, 21: 447-455. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00489.x.

Mogren IM: BMI, pain and hyper-mobility are determinants of long-term outcome for women with low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Eur Spine J. 2006, 15: 1093-1102. 10.1007/s00586-005-0004-9.

Mogren IM: Does caesarean section negatively influence the post-partum prognosis of low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy?. Eur Spine J. 2007, 16: 115-121. 10.1007/s00586-006-0098-8.

Mogren IM: Physical activity and persistent low back pain and pelvic pain post partum. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8: 417-10.1186/1471-2458-8-417.

Morkved S, Salvesen KA, Schei B, Lydersen S, Bo K: Does group training during pregnancy prevent lumbopelvic pain? a randomized clinical trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007, 86: 276-282. 10.1080/00016340601089651.

Mousavi SJ, Parnianpour M, Vleeming A: Pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain and low back pain in an Iranian population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007, 32: E100-E104.

Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL, McGovern EE: Outcome of pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain treated according to a diagnosis-based decision rule: a prospective observational cohort study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009, 32: 616-624. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.09.002.

Olsson C, Buer N, Holm K, Nilsson-Wikmar L: Lumbopelvic pain associated with catastrophizing and fear-avoidance beliefs in early pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009, 88: 378-385. 10.1080/00016340902763210.

Paterson LQ, Davis SN, Khalife S, Amsel R, Binik YM: Persistent genital and pelvic pain after childbirth. J Sex Med. 2009, 6: 215-221. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01063.x.

Pitts MK, Ferris JA, Smith AM, Shelley JM, Richters J: Prevalence and correlates of three types of pelvic pain in a nationally representative sample of Australian women. Med J Aust. 2008, 189: 138-143.

Robinson HS, Eskild A, Heiberg E, Eberhard-Gran M: Pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy: the impact on function. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006, 85: 160-164. 10.1080/00016340500410024.

Ronchetti I, Vleeming A, van Wingerden JP: Physical characteristics of women with severe pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a descriptive cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008, 33: E145-E151.

Rost CC, Jacqueline J, Kaiser A, Verhagen AP, Koes BW: Prognosis of women with pelvic pain during pregnancy: a long-term follow-up study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006, 85: 771-777. 10.1080/00016340600626982.

Rustamova S, Predanic M, Sumersille M, Cohen WR: Changes in symphysis pubis width during labor. J Perinat Med. 2009, 37: 370-373. 10.1515/JPM.2009.051.

Sjodahl J, Kvist J, Gutke A, Oberg B: The postural response of the pelvic floor muscles during limb movements: a methodological electromyography study in parous women without lumbopelvic pain. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2009, 24: 183-189. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.11.004.

Skaggs CD, Prather H, Gross G, George JW, Thompson PA, Nelson DM: Back and pelvic pain in an underserved United States pregnant population: a preliminary descriptive survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007, 30: 130-134. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.12.008.

Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW: Is there a relationship between parity, pregnancy, back pain and incontinence?. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008, 19: 205-211. 10.1007/s00192-007-0421-x.

Stuge B, Holm I, Vollestad N: To treat or not to treat postpartum pelvic girdle pain with stabilizing exercises?. Man Ther. 2006, 11: 337-343. 10.1016/j.math.2005.07.004.

Van De Pol G, Van Brummen HJ, Bruinse HW, Heintz AP, Van Der Vaart CH: Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain in the Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007, 86: 416-422. 10.1080/00016340601151683.

Van Kessel-Cobelens AM, Verhagen AP, Mens JM, Snijders CJ, Koes BW: Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: intertester reliability of 3 tests to determine asymmetric mobility of the sacroiliac joints. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008, 31: 130-136. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.12.003.

Van Vugt AB: [Pelvic pain in pregnancy: mechanical factors play a role. Indication for surgical treatment. Pro-contra] (in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2009, 153: 378.

Van Wingerden JP, Vleeming A, Ronchetti I: Differences in standing and forward bending in women with chronic low back or pelvic girdle pain: indications for physical compensation strategies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008, 33: E334-E341.

Vollestad NK, Stuge B: Prognostic factors for recovery from postpartum pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2009, 18: 718-726. 10.1007/s00586-009-0911-2.

Wang SM, Dezinno P, Lin EC, Lin H, Yue JJ, Berman MR, Braveman F, Kain ZN: Auricular acupuncture as a treatment for pregnant women who have low back and posterior pelvic pain: a pilot study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009, 201: 271-e271-e279

Wu WH, Meijer OG, Bruijn SM, Hu H, van Dieen JH, Lamoth CJ, van Royen BJ, Beek PJ: Gait in pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: amplitudes, timing, and coordination of horizontal trunk rotations. Eur Spine J. 2008, 17: 1160-1169. 10.1007/s00586-008-0703-0.

Pelvic Girdle Pain and problems at work. [http://www.mumsnet.com/Talk/pregnancy/185898-pelvic-girdle-pain-and-problems-at-work]

Pelvic Instability Network Support (PINS): providing information, ideas and online support. [http://www.pelvicgirdlepain.com/]

Pelvic Instability Network Scotland. [http://www.pelvicinstability.org.uk/healthprofessionals.asp]

The International Pelvic Pain Society (IPPS). [http://www.pelvicpain.org/]

Noren L, Ostgaard S, Nielsen TF, Östgaard HC: Reduction of sick leave for lumbar back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997, 22: 2157-2160.

Östgaard HC: [Two types of back pain during pregnancy: lumbar pain and pelvic pain] (in Swedish). Lakartidningen. 1997, 94: 233-235.

Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Stuge B, Sturesson B: Working Group 4: pelvic girdle pain. European Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pelvic Girdle Pain. 2005, European Commission, Research Directorate-General, Department of Policy, Coordination and Strategy

Hansen A, Jensen DV, Wormslev M, Minck H, Johansen S, Larsen EC, Wilken-Jensen C, Davidsen M, Hansen TM: Symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation in pregnancy. II: Symptoms and clinical signs. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999, 78: 111-115. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780207.x.

Kogstad O, Biørnstad N: [Pelvic girdle relaxation: pathogenesis, etiology, definition, epidemiology] (in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1990, 110: 2209-2211.

Moen MH, Kogstad O, Biørnstad N, Hansen JH, Sudmann E: [Symptomatic pelvic girdle relaxation: clinical aspects] (in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1990, 110: 2211-2212.

Saugstad LF: Is persistent pelvic pain and pelvic joint instability associated with early menarche and with oral contraceptives?. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991, 41: 203-206. 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90025-G.

Berezin D: Pelvic insufficiency during pregnancy and after parturition: a clinical study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1954, 33: 3-119. 10.3109/00016345409154960.

de WIT J: [Orthostatic disorders in pregnancy and the syndrome of pelvic insufficiency] (in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1960, 104: 2613-2617.

Wist A: Treatment of symphysiolysis with hydrocortisone-procaine injections. Ann Chir Gynaecol Fenn. 1968, 57: 98-100.

Bjorklund K, Naessen T, Nordstrom ML, Bergstrom S: Pregnancy-related back and pelvic pain and changes in bone density. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999, 78: 681-685. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780804.x.

Foulkes JF: Hereditary pelvic arthropathy of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1957, 64: 131-10.1111/j.1471-0528.1957.tb02611.x.

Walde J: Obstetrical and gynecological back and pelvic pains, especially those contracted during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1962, 41 (Suppl 2): 11-53. 10.3109/00016346209157174.

Driessen F: Postpartum pelvic arthropathy with unusual features. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987, 94: 870-872. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb03757.x.

Goldsmith LT, Weiss G: Relaxin in human pregnancy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009, 1160: 130-135. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03800.x.

Hansen A, Jensen DV, Larsen E, Wilken-Jensen C, Petersen LK: Relaxin is not related to symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation in pregnant women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996, 75: 245-249. 10.3109/00016349609047095.

Kristiansson P, Svardsudd K, von Schoultz B: Reproductive hormones and aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen in serum as early markers of pelvic pain during late pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999, 180: 128-134. 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70162-6.

MacLennan AH, Nicolson R, Green RC, Bath M: Serum relaxin and pelvic pain of pregnancy. Lancet. 1986, 2: 243-245. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92069-6.

Aslan E, Fynes M: Symphysial pelvic dysfunction. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007, 19: 133-139. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328034f138.

Mens JM, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Stam HJ, Snijders CJ: Understanding peripartum pelvic pain. Implications of a patient survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996, 21: 1363-1370.

Östgaard HC, Andersson GB, Schultz AB, Miller JA: Influence of some biomechanical factors on low-back pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993, 18: 61-65.

Mogren IM, Pohjanen AI: Low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy: prevalence and risk factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005, 30: 983-991.

Larsen EC, Wilken-Jensen C, Hansen A, Jensen DV, Johansen S, Minck H, Wormslev M, Davidsen M, Hansen TM: Symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation in pregnancy. I: prevalence and risk factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999, 78: 105-110. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780206.x.

O'Sullivan PB, Beales DJ: Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders. Part 1: a mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework. Man Ther. 2007, 12: 86-97.

Bastiaanssen JM, de Bie RA, Bastiaenen CH, Essed GG, van den Brandt PA: A historical perspective on pregnancy-related low back and/or pelvic girdle pain. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005, 120: 3-14. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.021.

Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JM, van Dieen JH, Wuisman PI, Östgaard HC: Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. Eur Spine J. 2004, 13: 575-589. 10.1007/s00586-003-0615-y.

MacLennan AH, MacLennan SC: Symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation of pregnancy, postnatal pelvic joint syndrome and developmental dysplasia of the hip. The Norwegian Association for Women with Pelvic Girdle Relaxation (Landforeningen for Kvinner Med Bekkenløsningsplager). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997, 76: 760-764. 10.3109/00016349709024343.

Fry D, Hay-Smith J, Hough J, McIntosh J, Polden M, Shepherd J, Watkins Y: National clinical guidelines for the care of women with symphysis pubis dysfunction. Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Women's Health. Midwives. 1997, 110: 172-173.

Albert HB, Godskesen M, Westergaard JG: Incidence of four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002, 27: 2831-2834.

Östgaard HC, Roos-Hansson E, Zetherstrom G: Regression of back and posterior pelvic pain after pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996, 21: 2777-2780.

Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J: Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001, 80: 505-510. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2001.080006505.x.

Noren L, Ostgaard S, Johansson G, Östgaard HC: Lumbar back and posterior pelvic pain during pregnancy: a 3-year follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2002, 11: 267-271. 10.1007/s00586-001-0357-7.

Foley BS, Buschbacher RM: Sacroiliac joint pain: anatomy, biomechanics, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006, 85: 997-1006. 10.1097/01.phm.0000247633.68694.c1.

Timsit MA: [Pregnancy, low-back pain and pelvic girdle pain] (in French). Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2004, 32: 420-426. 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2003.06.004.

Vermani E, Mittal R, Weeks A: Pelvic girdle pain and low back pain in pregnancy: a review. Pain Pract. 2010, 10: 60-71. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00327.x.

Saugstad LF: Persistent pelvic pain and pelvic joint instability. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991, 41: 197-201. 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90024-F.

Depledge J, McNair PJ, Keal-Smith C, Williams M: Management of symphysis pubis dysfunction during pregnancy using exercise and pelvic support belts. Phys Ther. 2005, 85: 1290-1300.

Sturesson B, Uden G, Uden A: Pain pattern in pregnancy and "catching" of the leg in pregnant women with posterior pelvic pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997, 22: 1880-1884.

Östgaard HC, Zetherstrom G, Roos-Hansson E, Svanberg B: Reduction of back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994, 19: 894-900.

Kristiansson P, Svardsudd K, von Schoultz B: Back pain during pregnancy: a prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996, 21: 702-709.

Wu W, Meijer OG, Lamoth CJ, Uegaki K, van Dieen JH, Wuisman PI, de Vries JI, Beek PJ: Gait coordination in pregnancy: transverse pelvic and thoracic rotations and their relative phase. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2004, 19: 480-488. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.02.003.

Sequeira W: Diseases of the pubic symphysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1986, 16: 11-21. 10.1016/0049-0172(86)90039-9.

Winterfeld HJ, Kunz B, Prenzlau P: [Exacerbation of chronic postpartum inflammation of the ileosacral joint] (in German). Zentralbl Gynakol. 1982, 104: 1115-1119.

Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Ronchetti I, Stam HJ: Reliability and validity of hip adduction strength to measure disease severity in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002, 27: 1674-1679.

Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Koes BW, Stam HJ: Validity of the active straight leg raise test for measuring disease severity in patients with posterior pelvic pain after pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002, 27: 196-200.

Broadhurst NA, Bond MJ: Pain provocation tests for the assessment of sacroiliac joint dysfunction. J Spinal Disord. 1998, 11: 341-345. 10.1097/00002517-199808000-00013.

Östgaard HC, Zetherstrom G, Roos-Hansson E: The posterior pelvic pain provocation test in pregnant women. Eur Spine J. 1994, 3: 258-260.

Crichton MA, Wellock VK: Research into symphysis pubis dysfunction (SPD). Pract Midwife. 2003, 6: 38-author reply 40

Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard JG, Chard T, Gunn L: Circulating levels of relaxin are normal in pregnant women with pelvic pain. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997, 74: 19-22. 10.1016/S0301-2115(97)00076-6.

Hansen A, Jensen DV, Larsen EC, Wilken-Jensen C, Kaae BE, Frolich S, Thomsen HS, Hansen TM: Postpartum pelvic pain-the "pelvic joint syndrome": a follow-up study with special reference to diagnostic methods. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005, 84: 170-176.

Chamberlain WE: The symphysis pubis in the roentgen examination of the sacroiliac joint. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther. 1930, 24: 621-625.

Williams PR, Thomas DP, Downes EM: Osteitis pubis and instability of the pubic symphysis: when nonoperative measures fail. Am J Sports Med. 2000, 28: 350-355.

Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ, Ginai AZ: The active straight leg raising test and mobility of the pelvic joints. Eur Spine J. 1999, 8: 468-473. 10.1007/s005860050206.

Babarinsa IA, Adewole IF, Fatade AO, Ajayi AB: Obstetric pubic symphysis arthropathy: a study of nine cases. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999, 19: 620-622. 10.1080/01443619963879.

Snow RE, Neubert AG: Peripartum pubic symphysis separation: a case series and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1997, 52: 438-443. 10.1097/00006254-199707000-00023.

Bjorklund K, Bergstrom S, Lindgren PG, Ulmsten U: Ultrasonographic measurement of the symphysis pubis: a potential method of studying symphyseolysis in pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1996, 42: 151-153. 10.1159/000291932.

Coventry MB, Tapper EM: Pelvic instability: a consequence of removing iliac bone for grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972, 54: 83-101.

Hodge JC, Bessette B: The incidence of sacroiliac joint disease in patients with low-back pain. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1999, 50: 321-323.

Shibata Y, Shirai Y, Miyamoto M: The aging process in the sacroiliac joint: helical computed tomography analysis. J Orthop Sci. 2002, 7: 12-18. 10.1007/s776-002-8407-1.

Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Volkers AC, Snijders CJ: Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part I: Clinical anatomical aspects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990, 15: 130-132.

Gibbon WW, Hession PR: Diseases of the pubis and pubic symphysis: MR imaging appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997, 169: 849-853.

Kurzel RB, Au AH, Rooholamini SA, Smith W: Magnetic resonance imaging of peripartum rupture of the symphysis pubis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996, 87: 826-829.

Wurdinger S, Humbsch K, Reichenbach JR, Peiker G, Seewald HJ, Kaiser WA: MRI of the pelvic ring joints postpartum: normal and pathological findings. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002, 15: 324-329. 10.1002/jmri.10073.

Bjorklund K, Lindgren PG, Bergstrom S, Ulmsten U: Sonographic assessment of symphyseal joint distention intra partum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997, 76: 227-232.

Weber K, Mahlfeld A, Otto W: [Value of ultrasound examination in injuries of the symphysis] (in German). Unfallchirurgie. 1996, 22: 36-38. 10.1007/BF02627460.

Dreyfuss P, Michaelsen M, Pauza K, McLarty J, Bogduk N: The value of medical history and physical examination in diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996, 21: 2594-2602.

Tettambel MA: Using integrative therapies to treat women with chronic pelvic pain. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007, 107 (10 Suppl 6): ES17-ES20.

Pennick VE, Young G: Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, CD001139-2

Kihlstrand M, Stenman B, Nilsson S, Axelsson O: Water-gymnastics reduced the intensity of back/low back pain in pregnant women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999, 78: 180-185. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780302.x.

Nilsson-Wikmar L, Holm K, Oijerstedt R, Harms-Ringdahl K: Effect of three different physical therapy treatments on pain and activity in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: a randomized clinical trial with 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up postpartum. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005, 30: 850-856.

Suputtitada A, Wacharapreechanont T, Chaisayan P: Effect of the "sitting pelvic tilt exercise" during the third trimester in primigravidas on back pain. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002, 85 (Suppl 1): S170-S179.

Stuge B, Hilde G, Vollestad N: Physical therapy for pregnancy-related low back and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003, 82: 983-990.

Kvorning N, Holmberg C, Grennert L, Aberg A, Akeson J: Acupuncture relieves pelvic and low-back pain in late pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004, 83: 246-250.

Wedenberg K, Moen B, Norling A: A prospective randomized study comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy for low-back and pelvic pain in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000, 79: 331-335. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079005331.x.

Mogren IM: Previous physical activity decreases the risk of low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Scand J Public Health. 2005, 33: 300-306.

Stuge B, Laerum E, Kirkesola G, Vollestad N: The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004, 29: 351-359.

Mens JM, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ: Diagonal trunk muscle exercises in peripartum pelvic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2000, 80: 1164-1173.

Ostensen ME, Skomsvoll JF: Anti-inflammatory pharmacotherapy during pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004, 5: 571-580. 10.1517/14656566.5.3.571.

Fuller JG, Janzen J, Gambling DR: Epidural analgesia in the management of symptomatic symphysis pubis diastasis. Obstet Gynecol. 1989, 73: 855-857.

Scicluna JK, Alderson JD, Webster VJ, Whiting P: Epidural analgesia for acute symphysis pubis dysfunction in the second trimester. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004, 13: 50-52. 10.1016/j.ijoa.2003.08.006.

Luukkainen RK, Wennerstrand PV, Kautiainen HH, Sanila MT, Asikainen EL: Efficacy of periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in non-spondylarthropathic patients with chronic low back pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002, 20: 52-54.

Maugars Y, Mathis C, Berthelot JM, Charlier C, Prost A: Assessment of the efficacy of sacroiliac corticosteroid injections in spondylarthropathies: a double-blind study. Br J Rheumatol. 1996, 35: 767-770. 10.1093/rheumatology/35.8.767.

Belanger TA, Dall BE: Sacroiliac arthrodesis using a posterior midline fascial splitting approach and pedicle screw instrumentation: a new technique. J Spinal Disord. 2001, 14: 118-124. 10.1097/00002517-200104000-00005.

Giannikas KA, Khan AM, Karski MT, Maxwell HA: Sacroiliac joint fusion for chronic pain: a simple technique avoiding the use of metalwork. Eur Spine J. 2004, 13: 253-256. 10.1007/s00586-003-0620-1.

Van Zwienen CM, van den Bosch EW, Snijders CJ, van Vugt AB: Triple pelvic ring fixation in patients with severe pregnancy-related low back and pelvic pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004, 29: 478-484.

Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Hart S, Theakston H, Schanberg S, Kuhn C: Pregnant women benefit from massage therapy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1999, 20: 31-38. 10.3109/01674829909075574.

Mantle MJ, Holmes J, Currey HL: Backache in pregnancy II: prophylactic influence of back care classes. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1981, 20: 227-232. 10.1093/rheumatology/20.4.227.

Thomas IL, Nicklin J, Pollock H, Faulkner K: Evaluation of a maternity cushion (Ozzlo pillow) for backache and insomnia in late pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989, 29: 133-138. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1989.tb01702.x.

Daly JM, Frame PS, Rapoza PA: Sacroiliac subluxation: a common, treatable cause of low-back pain in pregnancy. Fam Pract Res J. 1991, 11: 149-159.

Carr CA: Use of a maternity support binder for relief of pregnancy-related back pain. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32: 495-502. 10.1177/0884217503255196.

Gevargez A, Groenemeyer D, Schirp S, Braun M: CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency denervation of the sacroiliac joint. Eur Radiol. 2002, 12: 1360-1365. 10.1007/s00330-001-1257-2.

Coldron Y, Crothers E, Haslam J, Notcutt W, Sidney D, Thomas R, Watson T: ACPWH guidance on the safe use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for musculosketal pain during pregnancy. [http://www.oaa-anaes.ac.uk/assets/_managed/editor/File/PDF/info_for_mothers/TENS%20Statement%20JUNE%2007%20ACPWH%20Final.pdf]

Gherman RB, Ouzounian JG, Incerpi MH, Goodwin TM: Symphyseal separation and transient femoral neuropathy associated with the McRoberts' maneuver. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998, 178: 609-610. 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70447-8.

Guidance for Health Professionals: Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain; formerly known as Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction (SPD). [http://www.acpwh.org.uk/docs/ACPWH-PGP_HP.pdf]

Lindsey RW, Leggon RE, Wright DG, Nolasco DR: Separation of the symphysis pubis in association with childbearing: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988, 70: 289-292.

Owens K, Pearson A, Mason G: Symphysis pubis dysfunction: a cause of significant obstetric morbidity. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002, 105: 143-146.

Slatis P, Eskola A: External fixation of the pelvic girdle as a test for assessing instability of the sacro-iliac joint. Ann Med. 1989, 21: 369-372. 10.3109/07853898909149223.

Walheim GG: Stabilization of the pelvis with the Hoffmann frame: an aid in diagnosing pelvic instability. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984, 55: 319-324. 10.3109/17453678408992365.

To WW, Wong MW: Factors associated with back pain symptoms in pregnancy and the persistence of pain 2 years after pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003, 82: 1086-1091. 10.1046/j.1600-0412.2003.00235.x.

Grotle M, Brox JI, Veierod MB, Glomsrod B, Lonn JH, Vollestad NK: Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: patients consulting primary care for the first time. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005, 30: 976-982.

Golighty R: Pelvic arthropathy in pregnancy and the puerperium. Physiotherapy. 1982, 68: 216-220.

Young J: Pelvic Osteo-arthropathy of pregnancy: (Section of Obstetrics and Gynaecology). Proc R Soc Med. 1939, 32: 1591-1597.

Garces Cuadra O: [Treatment of pelvic arthropathy of pregnancy with dexamethasone] (in Spanish). Bol Soc Chil Obstet Ginecol. 1960, 25: 277-281.

Percy-Lancaster R: Pelvic arthropathy. S Afr Med J. 1969, 43: 551-557.

Golden A: Lesions of ischium and pubis in pregnancy resembling osteitis. J Urol. 1952, 67: 370-373.

Valenzuela F, Contreras V, Lackington C: Osteitis pubis (not following urological operation). Arch Interam Rheumatol. 1963, 20: 284-288.

Lenartowski E: [Case of osteitis pubis following normal labor with a follow-up of 9 years] (in Polish). Wiad Lek. 1971, 24: 587-590.

Gonik B, Stringer CA: Postpartum osteitis pubis. South Med J. 1985, 78: 213-214.

Berezin D: Pelvic insufficiency during pregnancy and after parturition. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1950, 30 (Suppl 7): 170-182. 10.3109/00016345009164771.

Genell S: Studies on insufficientia pelvis (gravidarum et puerperarum). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1949, 28: 1-37. 10.3109/00016344809154876.

Ostergaard M, Bonde B, Thomsen BS: [Pelvic insufficiency during pregnancy: is pelvic girdle relaxation an unambiguous concept?] (in Danish). Ugeskr Laeger. 1992, 154: 3568-3572.

Wormslev M, Juul AM, Marques B, Minck H, Bentzen L, Hansen TM: Clinical examination of pelvic insufficiency during pregnancy: an evaluation of the interobserver variation, the relation between clinical signs and pain and the relation between clinical signs and physical disability. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994, 23: 96-102. 10.3109/03009749409103036.

Fernandez-Ruiz C, De Crespo LV: [Lumbosacral pains in pregnancy and painful relaxation of the pelvic joints]. Bol Cult Inf Cons Gen Col Med Esp. 1956, 19: 7-10.

Hagen R: Pelvic girdle relaxation from an orthopaedic point of view. Acta Orthop Scand. 1974, 45: 550-563. 10.3109/17453677408989178.

Nichols DH: Effects of pelvic relaxation on gynecologic urologic problems. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1978, 21: 759-774. 10.1097/00003081-197809000-00012.

Porges RF, Porges JC: Theoretical and practical aspects of the surgical correction of pelvic relaxation. Obstet Gynecol. 1967, 29: 450-455.

Ulrych J, Cernoch A: [Progesterone in relaxation of the pelvic conjunctions during pregnancy] (in Czech). Cesk Gynekol. 1973, 38: 655-656.

Wright JL: Relaxation of the pelvic joints in pregnancy; a report of three cases. N Z Med J. 1952, 51: 377-380.

Slate WG, Mengert WF: Effect of the relaxing hormone on the laboring human uterus. Obstet Gynecol. 1960, 15: 409-414.

Abramson D, Roberts SM, Wilson PD: Relaxation of the pelvic joints in pregnancy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1934, 58: 595-613.

Evensen AR: [Pelvic girdle relaxation] (in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1990, 110: 2179-2180.

Dietrichs E, Kogstad O: "Pelvic girdle relaxation": suggested new nomenclature. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1991, 88: 3.

Andersen K: [Pelvic girdle relaxation and physiotherapy: prevention and treatment] (in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1992, 112: 1489-1490.

Bånerud BS, Helmert M, Larun L: [Pelvic relaxation and physiotherapy: prevention and treatment] (in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1992, 112: 349-351.

Gurel H, Gurel SA: Pelvic relaxation and associated risk factors: the results of logistic regression analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999, 78: 290-293. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780403.x.

Moen MH, Tingulstad S: [Pelvic joint syndrome as the cause of chronic pelvic pain in women] (in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1991, 111: 690-691.

Gregersen E, Olander V: [Pelvic instability: changed treatment of pelvic instability in the last year] (in Danish). Sygeplejersken. 1984, 84: 5-6.

Irgens S, Lindsel H: [Pelvic instability: we have written from our own experience] (in Danish). Sygeplejersken. 1984, 84: 8.

Johansen T, Nickelsen C: [Surgical treatment of pelvic ring instability: a case with symptoms 15 months post partum] (in Danish). Ugeskr Laeger. 1983, 145: 2097-2098.

Lindsel H, Irgens S: [Pelvic instability: important that maternity centers are informed and know about women's condition] (in Danish). Sygeplejersken. 1984, 84: 4-7. 14

Reeberg L: [Pelvic instability: prejudice will disappear in time with added knowledge] (in Danish). Sygeplejersken. 1984, 84: 6-7.

Lindsel H, Irgens S: [Pelvic instability. It is all about relief and avoiding pain] (in Danish). Sygeplejersken. 1984, 84: 4-8.

Blom B: [Pelvic instability: waited in bed for 3 months. Interview by Lisbet Harstad] (in Norwegian). Jordmorbladet. 1994, 3: 21-23.

Brendbekken G: [Pelvic training important in pelvic instability] (in Norwegian). Jordmorbladet. 1994, 3: 14-16.

Hansen JH: [Pelvic instability: pain and functional impairment can vary greatly] (in Norwegian). Jordmorbladet. 1994, 3: 17-19.

Kogstad O: [Pelvic instability: a controversial diagnosis] (in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1988, 108: 1115-1119.

Renckens CN: Between hysteria and quackery: some reflections on the Dutch epidemic of obstetric 'pelvic instability'. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000, 21: 235-239. 10.3109/01674820009085593.

Mitchell DA, Esler DM: Pelvic instability: painful pelvic girdle in pregnancy. Aust Fam Physician. 2009, 38: 409-410.

Bjorklund K, Nordstrom ML, Bergstrom S: Sonographic assessment of symphyseal joint distention during pregnancy and post partum with special reference to pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999, 78: 125-130. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780210.x.

Young G: More women with the pelvic girdle syndrome than with other pelvic pain during pregnancy had pelvic pain 2 years after delivery. ACP J Club. 2002, 136: 33.

Bastiaenen CH, de Bie RA, Wolters PM, Vlaeyen JW, Bastiaanssen JM, Klabbers AB, Heuts A, van den Brandt PA, Essed GG: Treatment of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle and/or low back pain after delivery design of a randomized clinical trial within a comprehensive prognostic cohort study [ISRCTN08477490]. BMC Public Health. 2004, 4: 67-10.1186/1471-2458-4-67.

Ferreira P: Specific stabilising exercise improves pain and function in women with pelvic girdle pain following pregnancy. Aust J Physiother. 2004, 50: 259.

Stuge B, Veierod MB, Laerum E, Vollestad N: The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a two-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004, 29: E197-E203.

Elden H, Ladfors L, Olsen MF, Östgaard HC, Hagberg H: Effects of acupuncture and stabilising exercises as adjunct to standard treatment in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: randomised single blind controlled trial. BMJ. 2005, 330: 761-10.1136/bmj.38397.507014.E0.

Stones RW, Vits K: Pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. BMJ. 2005, 331: 249-250. 10.1136/bmj.331.7511.249.

Nordin M: Comments about "European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain". Eur Spine J. 2008, 17: 820-821. 10.1007/s00586-008-0649-2.

Mateos Fournier M: [Pelvic pain during pregnancy] (in Spanish). Ginecol Obstet Mex. 1958, 13: 50-60.

Carpenter TJ: Pregnancy as a cause of chronic pelvic pain. Postgrad Med. 1994, 95: 31, 132.

Shuler TE, Gruen GS: Chronic postpartum pelvic pain treated by surgical stabilization. Orthopedics. 1996, 19: 687-689.

Van Dongen PW, de Boer M, Lemmens WA, Theron GB: Hypermobility and peripartum pelvic pain syndrome in pregnant South African women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999, 84: 77-82. 10.1016/S0301-2115(98)00307-8.

Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH: Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999, 106: 1149-1155. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08140.x.

Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J: Evaluation of clinical tests used in classification procedures in pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Eur Spine J. 2000, 9: 161-166. 10.1007/s005860050228.

Bjorklund K, Bergstrom S: Is pelvic pain in pregnancy a welfare complaint?. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000, 79: 24-30. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079001024.x.

Bjorklund K, Bergstrom S, Nordstrom ML, Ulmsten U: Symphyseal distention in relation to serum relaxin levels and pelvic pain in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000, 79: 269-275. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079004269.x.

Hansen A, Jensen DV, Wormslev M, Minck H, Johansen S, Larsen EC, Wilken-Jensen C, Davidsen M, Hansen TM: [Pregnancy associated pelvic pain. II: symptoms and clinical findings] (in Danish). Ugeskr Laeger. 2000, 162: 4813-4817.

Larsen EC, Wilken-Jensen C, Hansen A, Jensen DV, Johansen S, Minck H, Wormslev M, Davidsen M, Hansen TM: [Pregnancy associated pelvic pain. I: prevalence and risk factors] (in Danish). Ugeskr Laeger. 2000, 162: 4808-4812.

Randriamiarisoa NA, Andriamady RC, Ranjalahy RJ, Rakotomanga S: [Epidemiological aspects of acute pelvic pain of gynecologic origin at the maternity of the Befelatanana Hospital Center, Antananarivo] (in French). Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 2000, 66: 72-74.

Thomas CT, Napolitano PG: Use of acupuncture for managing chronic pelvic pain in pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2000, 45: 944-946.

Damen L, Buyruk HM, Guler-Uysal F, Lotgering FK, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ: The prognostic value of asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints in pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002, 27: 2820-2824.

Vleeming A, de Vries HJ, Mens JM, van Wingerden JP: Possible role of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament in women with peripartum pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002, 81: 430-436.

Wu W, Meijer OG, Jutte PC, Uegaki K, Lamoth CJ, Sander de Wolf G, van Dieën JH, Wuisman PI, Kwakkel G, de Vries JI, Beek PJ: Gait in patients with pregnancy-related pain in the pelvis: an emphasis on the coordination of transverse pelvic and thoracic rotations. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2002, 17: 678-686. 10.1016/S0268-0033(02)00109-2.

Juhl M, Andersen PK, Olsen J, Andersen AM: Psychosocial and physical work environment, and risk of pelvic pain in pregnancy: a study within the Danish national birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005, 59: 580-585. 10.1136/jech.2004.029520.

Kumle M, Weiderpass E, Alsaker E, Lund E: Use of hormonal contraceptives and occurrence of pregnancy-related pelvic pain: a prospective cohort study in Norway. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004, 4: 11-10.1186/1471-2393-4-11.

Rost CC, Jacqueline J, Kaiser A, Verhagen AP, Koes BW: Pelvic pain during pregnancy: a descriptive study of signs and symptoms of 870 patients in primary care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004, 29: 2567-2572.

Eyvazzadeh AD, Levine D: Imaging of pelvic pain in the first trimester of pregnancy. Radiol Clin North Am. 2006, 44: 863-877. 10.1016/j.rcl.2006.10.015.

Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Koes BW, Stam HJ: Reliability and validity of the active straight leg raise test in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001, 26: 1167-1171.

Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Ronchetti I, Ginai AZ, Stam HJ: Responsiveness of outcome measurements in rehabilitation of patients with posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002, 27: 1110-1115.

Reiter RC, Gambone JC: Demographic and historic variables in women with idiopathic chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1990, 75: 428-432.

Engelen MJ, Diercks RL, Mensink WF: [Pelvic pain and pregnancy] (in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1995, 139: 1961-1964.

Pel M: [Pelvic pain caused by pregnancy] (in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1995, 139 (49): 2586-2587.

Buyruk HM, Stam HJ, Snijders CJ, Lameris JS, Holland WP, Stijnen TH: Measurement of sacroiliac joint stiffness in peripartum pelvic pain patients with Doppler imaging of vibrations (DIV). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999, 83: 159-163. 10.1016/S0301-2115(98)00331-5.

Endresen EH: Pelvic pain and low back pain in pregnant women: an epidemiological study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995, 24: 135-141. 10.3109/03009749509099301.

Gurel H, Atar Gurel S: Dyspareunia, back pain and chronic pelvic pain: the importance of this pain complex in gynecological practice and its relation with grandmultiparity and pelvic relaxation. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999, 48: 119-122. 10.1159/000010152.

Bjorklund K, Nordstrom ML, Odlind V: Combined oral contraceptives do not increase the risk of back and pelvic pain during pregnancy or after delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000, 79: 979-983.

Ternov NK, Grennert L, Aberg A, Algotsson L, Akeson J: Acupuncture for lower back and pelvic pain in late pregnancy: a retrospective report on 167 consecutive cases. Pain Med. 2001, 2: 204-207. 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2001.01031.x.

Young G, Jewell D: Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002, CD001139-1

Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Slieker ten Hove MC, Vierhout ME, Mulder PH, Pool JJ, Snijders CJ, Stoeckart R: Relations between pregnancy-related low back pain, pelvic floor activity and pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005, 16: 468-474. 10.1007/s00192-005-1292-7.

Naderi S: Comment on "Does caesarean section negatively influence the post-partum prognosis of low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy?" (Ingrid M. Mogren). Eur Spine J. 2007, 16: 123-10.1007/s00586-006-0130-z.

Ee CC, Manheimer E, Pirotta MV, White AR: Acupuncture for pelvic and back pain in pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 198: 254-259. 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.008.

Mens JM, Pool-Goudzwaard A, Stam HJ: Mobility of the pelvic joints in pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009, 64: 200-208. 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181950f1b.

Stuge B: Group training reduces the risk of pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain. Aust J Physiother. 2007, 53: 202.

Lee DG, Lee LJ, McLaughlin L: Stability, continence and breathing: the role of fascia following pregnancy and delivery. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2008, 12: 333-348. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2008.05.003.

Shepherd J: Research into symphysis pubis dysfunction (SPD). Pract Midwife. 2003, 6: 38-40.

Leadbetter RE, Mawer D, Lindow SW: Symphysis pubis dysfunction: a review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004, 16: 349-354. 10.1080/jmf.16.6.349.354.

Bastiaanssen JM, de Bie RA, Bastiaenen CH, Heuts A, Kroese ME, Essed GG, van den Brandt PA: Etiology and prognosis of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: design of a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2005, 5: 1-10.1186/1471-2458-5-1.

Bastiaenen CH, de Bie RA, Essed GG: Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007, 86: 1277-1279. 10.1080/00016340701659163.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/15/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests, the absence of any funding related to this article, no ethical approval was applicable, and there are no guarantors or acknowledgements.

Authors' contributions

NKK participated at the design of the article, the acquisition of the data from the reviewed articles, their analysis and interpretation and the initial drafting of the manuscript. CSR assisted with the preparation of the final manuscript. PVG conceived the article and participated in its design and the final revision of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanakaris, N.K., Roberts, C.S. & Giannoudis, P.V. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: an update. BMC Med 9, 15 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-15