Abstract

Background

Inappropriate use and overuse of antibiotics is a serious concern in the treatment of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), especially in developing countries. In recent decades, information disclosure and public reporting (PR) has become an instrument for encouraging good practice in healthcare. This study evaluated the impact of PR on antibiotic prescribing for URTIs in a sample of primary care institutions in China.

Methods

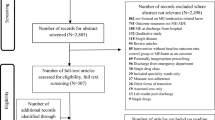

A matched-pair cluster-randomized trial was undertaken in QJ city, with 20 primary care institutions participating in the trial. Participating institutions were matched into pairs before being randomly assigned into a control and an intervention group. Prescription statistics were disclosed to patients, health authorities, and health workers monthly within the intervention group, starting from October 2013. Outpatient prescriptions for URTIs were collected from both groups before (1st March to 31st May, 2013) and after the intervention (1st March to 31st May, 2014). A total of 34,815 URTI prescriptions were included in a difference-in-difference analysis using multivariate linear or logistic regression models, controlling for patient attributes as well as institutional characteristics.

Results

Overall, 90% URTI prescriptions required antibiotics and 21% required combined use of antibiotics. More than 77% of URTI prescriptions required intravenous (IV) injection or infusion of drugs. PR resulted in a 9 percentage point (95% CI -17 to -1) reduction in the use of oral antibiotics (adjusted RR =39%, P =0.027), while the use of injectable antibiotics remained unchanged. PR led to a 7 percentage point reduction (95% CI -14 to 0; adjusted RR =36%) in combined use of antibiotics (P =0.049), which was largely driven by a significant reduction in male patients (-7.5%, 95% CI -14 to -1, P =0.03). The intervention had little impact on the use of IV injections or infusions, or the total prescription expenditure.

Conclusions

The results suggest that PR could improve prescribing practices in terms of reducing oral antibiotics and combined use of antibiotics; however, the impacts were limited. We suggest that PR would probably be enhanced by provider payment reform, management and training for providers, and health education for patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Inappropriate use and overuse of antibiotics is a serious concern, especially in developing countries such as China [1]. It is perhaps the most prominent manifestation of irrational drug prescribing and contributes to bacterial resistance, which is an emergent threat to the global population [2–4]. Nosocomial or hospital-acquired infection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has the capacity to increase medical costs, length of hospital stay, and ultimately patient mortality [5, 6].

Upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) are one of the most common health conditions seen by primary care workers, and the associated overuse of antibiotics is widespread [7]. In the UK, for example, general practitioners prescribe antibiotics to 67% of patients presenting with respiratory infections, including 47% of those with URTIs [8]. It was estimated that 60% of respiratory infections prescribed with antibiotics in the UK are self-limiting conditions [9]. A large cohort study of antibiotic usage associated with URTI in UK primary care settings concluded that prophylactic antibiotic prescriptions are unjustified in reducing the risk of serious complications in URTIs [10].

In China, approximately 75% of patients with seasonal influenza were estimated to be prescribed with antibiotics, more than doubled of the maximum rate (30%) recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. Several systematic reviews have shown that antibiotics are of limited effectiveness in the treatment of URTIs [11] and suggested no benefit in colds [12].

Growing public health concerns regarding the implications of inappropriate use and overuse of antibiotics have resulted in global action [13]; China is no exception. The recent health reform (2009–2011) in China articulated specific governance and incentive structures for public health organisations to address the issues of poor quality in prescribing, such as the enforcement of an essential medicine list policy and decoupling the nexus between medicine sales to health worker remuneration and bonus payments in primary care organisations [14]. Despite this, empirical evidence demonstrates that the effectiveness of these policy interventions has been short of expectations [15].

In recent decades, public reporting (PR) has started to attract attention as a vehicle for improving the performance of health organisations [16–20]. The United States has led the PR movement, along with the UK [21]. The rationale behind this approach draws experience from other industries with theoretical support from the domains of psychology, economics, and organizational behaviour. Public release of performance data is considered a bottom-up intervention compared with government regulation [22], and is intended to improve quality of care through imposing a higher level of transparency and accountability [23]. Frølich et al. believe that PR can provide both financial and reputational incentives for health providers to improve quality of care, although contextual factors (at the levels of the markets and provider organisation) and characteristics of providers and patients may enhance or mitigate their responses to those incentives [24]. Reputational incentives could also have financial implications.

This study aims to explore the potential use of PR for improving the quality of prescribing in primary care organisations using a social experiment. The study has important implications, primarily to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescription, but also as an analysis of whether greater transparency leads to improved healthcare outcomes. Provider-specific comparative performance reporting is currently being debated and implemented in a subset of developed countries, but only in a small group of developing countries [25]. Scant information is available regarding the effectiveness of PR in primary care settings, particularly in relation to prescribing behaviours. The concept of PR is almost completely novel for health workers in China.

Methods

Setting

This study was undertaken in QJ city of Hubei province, involving 20 primary care organisations. Hubei has a population of 58 million and a GDP of 2,225 billion (Yuan in 2012), ranking in the middle range of all Chinese provinces. QJ is located in central Hubei, with a land area of 2,004 km2 and a population of 1 million. The annual GDP of QJ reached 49.3 billion (Yuan) in 2012, just above the average level of all cities in Hubei. The majority of inhabitants in QJ are of Han ethnicity, with about 8,000 from Hui, Tujia, and other ethnic groups.

We selected QJ due to ready access to prescription data and implementation of intervention measures. Primary care organisations in QJ have the benefit of an electronic health information system (HIS). The QJ government has been very supportive of this project.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. IORG0003571).

Experimental design

This research adopted a matched-pair randomized trial design. The 20 participating primary care organisations were paired according to their size, geographic location and economic status, and population serviced. We considered all the organisational characteristics presented in Table 1 in the pair-matching process. The Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method was adopted to calculate a summed score from the matching variables (standardised) for each participating organisation. TOPSIS is a multi-criteria decision analysis method that estimates the geometric distance between each alternative and the ideal alternative to a given solution [26]. The participating organisations were ranked in order according to their distances to the positive and the negative ideal alternatives. Adjacent organisations were paired and assigned randomly to the intervention and control groups.

Participants in the intervention group and the control group were exposed to the same political, financial, and administrative environments: the only exception being the intervention measures. Identical training on appropriate prescription practice was offered to both intervention and control groups.

Intervention measures

The intervention measures were designed after considering the following assumptions [21, 27]:

-

Patient choice of healthcare providers: patients or potential consumers would make an informed choice of their preferred provider(s) based on reported prescription indicators, exerting consumer pressure on healthcare providers.

-

Use of reported data by regulators and managers: medical insurance authorities, local health authorities, and health organisation managers may use the reported data for decisions in payment (or reimbursement), health planning, and performance management, exerting financial and administrative pressure on healthcare providers (individual or institutional level).

-

Provider efforts to improve quality of care: physicians and healthcare organisations have intrinsic motivation to improve quality of care, especially if their quality of care falls below average.

The PR intervention started in October 2013. Three elements were included in the PR of this study: prescribing indicators were calculated using data extracted from the HIS on a monthly basis; healthcare providers (at both individual and institution levels) were ranked using the prescribing indicators and the reports were displayed in a public space in the primary care organisations in the intervention group; the monthly performance reports and league tables were submitted to local health authorities and organisational managers in the intervention group (see Public reporting package below). The reports also contained a brief explanation about the purpose of the PR intervention (i.e., to curb overuse of antibiotics). Administrative measures (e.g., meetings and newsletters) were taken to ensure that all prescribers in the intervention group were aware of the reports. However, there was no action taken to individually alert patients to the reports, although these reports (including poster displays and brochures) were readily available every day in a designated public space.

Public reporting package

-

1)

Timeline: Monthly reporting in the intervention group started in October 2013, which is still continuing at the time of writing.

-

2)

Reported indicators: Prescription indicators were calculated at both individual (physician) and institutional levels, including:

-

Percentage of prescriptions requiring antibiotics (%) = Number of prescriptions requiring antibiotics/total number of prescriptions by a physician (or institution) in one month × 100%.

-

Percentage of prescriptions requiring IV injections (%) = Number of prescriptions requiring IV injections/total number of prescriptions by a physician (or institution) in one month × 100%.

-

Expenditure per prescription (Yuan) = Total expenditure of prescriptions/total number of prescriptions by a physician (or institution) in one month.

-

-

3)

Dissemination: Prescribing physicians and hospitals were ranked in each of the above indicators. The league tables were publicly available to consumers and health workers alike, displayed on a bulletin board in the lobby of outpatient departments. Hard copies of the reports were also submitted to local health authorities and presidents of the hospitals in the intervention group.

-

4)

Update of reports: The reports were updated monthly and made available on the first week of each month.

To ensure compliance with the intervention, we sent trained investigators to the intervention sites at random to monitor the implementation of intervention measures on a monthly basis.

Data collection

Data pertaining to the characteristics of the participating organisations were extracted through their respective administrative systems prior to commencement of the PR intervention, covering the entire year of 2012. These included population serviced, number of outpatient visits, number of hospital admissions, bed numbers, number of doctors, gross revenue, revenue from drug sales, and revenue from government subsidies. The research team validated these data in interviews with managers and reconciled discrepancies as necessary.

Prescription data were drawn from the electronic HIS. For the purpose of this study, we collected unidentified prescription data from the participating organisations for a period of four months prior to the intervention (1st March to 31st May, 2013) and four months after start of the intervention (1st March to 31st May, 2014). All prescriptions associated with URTI were identified and collated for data analyses. The prescription data also contained demographic information (gender, age, insurance status) of the patients, tests and examinations ordered by the physicians, and expenditure in relation to the prescriptions.

Statistical analysis

The prescribing indicators used in this study were adapted from the WHO/International Network for the Rational Use of Drugs indicators, which have been used widely [2, 15, 28]. We examined the extent to which the PR intervention changed the prescribing patterns in relation to those indicators, such as:

-

1)

Percentage of prescriptions requiring antibiotics;

-

2)

Percentage of prescriptions requiring two or more antibiotics;

-

3)

Percentage of prescriptions requiring intravenous (IV) injection (peripheral IV administration using a syringe driver [29]);

-

4)

Percentage of prescriptions requiring infusion (medicines are introduced into a vein or between tissues by using an infusion pump or bag [29]);

-

5)

Expenditure per patient visit (including consultations, diagnostic tests, and prescriptions).

A difference-in-difference (DID) estimation of the above indicators was used in our study to assess the impact of the PR intervention on prescribing patterns. The DID method allows us to control confounding influences of independent variables, as well as imbalance between groups in baseline (dependent) variables (due to chances of imperfect randomisation).

We performed regression modelling for estimation of the effect size of PR. We reported both unadjusted estimates of effect size and those adjusted for characteristics of patients (age, sex and enrolment with the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS)) and hospitals (number of beds, number of doctors, population serviced, outpatient visits a year, inpatient admissions per annum, drug sales revenue per annum, variety of drugs in stock, percentage of drug sales in total revenue, and average revenue per doctor).

For binary dependent variables (in relation to indicator 1, 2, 3, and 4), we used logistic regression models. For a given patient i serviced within organisation j, the probability p ij of the occurrence of a dichotomous outcome y ij (i.e., value 1 for a patient receiving antibiotics, 0 otherwise) modelled as a logistic model can be expressed as:

and report marginal effects, where

-

i =1 . . . i patient, j =1. . . j primary care organisation;

-

T ij indicates ith patient receiving a prescription within jth primary care organisation before or after intervention (0 before or 1 after);

-

G ij indicates ith patient receiving a prescription within jth primary care organisation that had or had not implemented PR intervention (0 control or 1 intervention);

-

EFFECT ij = T ij * G ij , which measures invention effect and coefficient β e indicates the effect size;

-

o =1. . . o patient visit covariate, p =1. . .p primary care organisation covariate.

For the continuous dependent variable (in relation to indicator 5, log transformed), we used a least squares regression model, which can be expressed as:

X oij and X pij are the control (independent) variables. In addition, a dummy variable was generated to measure the cluster-pair fixed effect. Robust standard errors were clustered at the organisational level.

Coefficient β e in the regression model 1 and 2 is actually an estimation of the interaction between intervention and time, measuring the DID. For all of the outcome indicators, we conducted subgroup analyses by gender.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 10).

Results

Characteristics of participating organisations and patients

Similar characteristics of participating organisations were shown between intervention and control groups (Table 1). Each organisation served on average a population of 40,000 and provided 50,000 outpatient consultations per annum. A total of 34,815 prescriptions for URTI were deemed eligible for inclusion in the study. Those patients prescribed with antibiotics had a mean age of 23.6 years (Standard deviation =23.5); about half (49.5%) of them were male and over 85.9% were enrolled with the NCMS.

Prescriptions requiring antibiotics

High rates of antibiotic prescription were noted in both intervention and control groups (Table 2). Prior to the intervention, more than 90% of prescriptions for URTIs contained antibiotics.

The PR intervention led to only a slight reduction in the use of antibiotics, in particular for oral administration of antibiotics: a 9 percentage point reduction in oral administration of antibiotics was shown (P <0.05).

Paradoxically, there was an increase in the percentage of prescriptions requiring two or more antibiotics in both intervention and control groups; however, this increase was 7 percentage points less in the intervention group compared with that in the control group (P <0.05). This mainly occurred for male URTI patients (P =0.03), whereas the effect was statistically insignificant for female patients.

Prescriptions requiring IV injection or infusion

No significant differences were found between the intervention and control groups in the changes in percentage of prescriptions requiring IV injection or infusion (Table 3). Overall, the percentage of prescriptions requiring IV injection or infusion remained high during the period of study, with 77% to 90% of prescriptions for URTI requiring IV injection or infusion.

Average expenditure per visit

No significant differences were found between the intervention and control groups in average expenditure per visit (Table 3). Overall, the average expenditure per visit for URTI patients was low, ranging from 27 to 41 Yuan (roughly USD$5–7). The average expenditure per visit measured in the post-intervention period increased slightly compared to that in the pre-intervention period in both intervention and control groups. Such increase was 10% to 15% less in the intervention group than in the control group. However, the adjusted estimate of treatment effect was close to zero after controlling for independent variables.

Discussion

PR can have an impact on prescription patterns in primary care settings. This study demonstrated that PR interventions reduced the overall number of prescriptions associated with oral administrated antibiotics and retarded an anticipated potential rise in combined use of two or more antibiotics for URTIs. Although clinical outcomes of such a change were not explored in this study, it is reasonable to expect a positive outcome. Overuse of antibiotics is a widespread and serious problem in China [15, 28, 30], despite clinical guidelines for URTIs that advise against routine use of antibiotics [31]. Systematic reviews with meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials have shown minimal benefit associated with antibiotic prescriptions for URTIs [12, 32, 33]. Meanwhile, there are growing concerns about the possibility of antimicrobial resistance induced by irrational use of antibiotics. It was estimated that abuse of antibiotics for URTIs in low- and middle-income countries contributes to an additional 36% of medical costs [34]. Reducing irrational use of antibiotics can preserve these resources for more cost-effective interventions.

It is important to note that the overall use of antibiotics for URTIs in the participating primary care organisations remained at a high level despite the PR interventions. In addition, the PR interventions failed to show a significant impact on prescriptions using parenteral administration (injection and infusion). This study found that over 87% of prescriptions for URTIs contained antibiotics, much higher than the WHO recommendations [1]. The percentage of prescriptions requiring administration via IV injection and infusion for URTI reached a staggering level – over 77%. Arguably, IV injection and infusion are more likely to impose health risks for the public, leading to iatrogenic and nosocomial problems such as transmission of blood-borne viruses and infection of infusion sites [3].

The persistent high prevalence of antibiotic misuse probably reflects both inertia in physician practice and continued demand from patients. Nevertheless, many Chinese patients regard parenteral administration as integral to high-quality care [3]. The national zero-mark-up policy, introduced during 2009–2011, prohibits primary care organisations from generating excessive profits from retailing drugs, with the intention of making drugs more financially accessible. Health providers are wily and resourceful: fees can be charged in relation to injection or infusion services [35]. This may explain why the apparent consumer demand for antibiotics continues to be high, and why prescribing changes were mainly limited to oral antibiotics.

PR interventions did not have a significant effect on the average expenditure per visit. One plausible explanation could be that the expenditure had already been low due to a range of policies. The participating primary care organisations in both intervention and control groups had been exposed to the same policy environments over the past decade. Primary care organisations are only allowed to stock and provide drugs listed in the essential medicines list; these drugs can only be purchased through a regional centralized tendering and purchasing system at an agreed price; patients (and insurers) are charged with exactly the same purchasing price for their prescribed drugs. Empirical evidence showed that those policies have led to a significant reduction in drug expenditure [15]. Understandably, the capacity for further reduction of drug expenditure in primary care organisations is therefore limited.

There are policy implications arising from this study. Evidence from randomised control trials is regarded as the most robust and reliable. It is rare to find a study that uses a randomised control trial design to test the effect of PR interventions on physician prescribing practices within a complex health system and policy environment [16, 17, 21].

Internationally, healthcare systems are moving towards greater transparency and accountability [22]. Performance reporting in healthcare has been shown to improve the health systems of developed countries [16, 17, 21]. Despite this, reporting systems must be properly developed, considering a system-wide stakeholder participation, a change of organisational culture, and the accuracy and relevancy of reported data. It is also important to be mindful of minimising unintended consequences [36].

PR of prescription performance may impose “pressures” on prescribers arising from consumers, payers, managers, and colleagues. The magnitude of the pressure depends on the level of PR awareness and how the population understands it [24, 27, 37, 38].

We fear that consumer pressure to reduce irrational antibiotic and injectable prescription is limited in China, as the disclosed prescription indicators are difficult for consumers to understand due to limited health literacy. It is unlikely that the general public are either able or inclined to use the reported information to identify and choose healthcare providers. Previous studies show that consumer health literacy is low in China [39]; overuse of antibiotics is common; and physicians may be under pressure to prescribe more, not fewer, antibiotics [1]. The effect of PR on patients may also be jeopardised by limited exposure of patients to PR.

Pressure from payers is usually linked with financial incentives (or disincentives) [24, 40]. In this study, we found that the PR interventions are more likely to have an impact on the use of oral administered antibiotics compared with those administered via IV injection or infusion. This is perhaps because there are no financial incentives directly linked to reduction in irrational use of antibiotics, and fewer prescriptions of oral antibiotics (with zero-profit attached) are less likely to have a negative consequence on organisational revenues than reduced prescriptions of injected antibiotics (where a service fee can be charged). Clearly, these are demonstrable examples of perverse incentives.

Pressures from managers and colleagues may be a major driving force for the impact of PR interventions on prescribers. The working environment of physicians in China is characterised by strong administrative interventions from the government and organisations [41, 42]. Physician buy-in of PR is also essential for success; after all, they make the final prescription decision. Our experience, together with studies conducted elsewhere [43], show that physicians may challenge the validity of the PR and express concerns about performance reporting at individual levels for potential misinterpretations from patients. If a physician believes that the reported data are flawed (e.g., lack of adequate risk adjustment), he or she may be less likely to be influenced by the data. To make PR more acceptable, simplified data presentation, continued risk-adjustment refinement, and internal review before PR are necessary [43].

The development of an adequate PR system should be tailored to the macro- and micro-environment in which the healthcare organisations are operating [40]. Consumers and health care providers should be involved in the design and specification of information requirements, reporting approach, and communication strategies [23]. An ideal PR system should be able to assist patients or potential users to make better informed decisions [44]. Such a system should also address concerns from physicians in order to gain their acceptance [43]. A high quality information system is also critical for easy access and quality assurance of data. Translating good practice from one program to others is a practical approach for building high quality information systems [45]. Nevertheless, none of these measures are likely to take place if the income for services remains as a fee for service, and opportunities remain that maximise income through unnecessary drug administration practices.

Limitations

This study was undertaken during an early stage of PR interventions, which may underestimate the true impact of the interventions. PR does not have a direct impact on prescriber behaviours. It may take time for healthcare providers to understand the rationale underlying the PR interventions and subsequently to change management and clinical practices. The mechanisms and long term effect of PR on prescribing behaviours warrant further studies.

The positive but limited effect of PR on prescription outcomes might also be indicative of shortfalls in project design and implementations. For example, this project included a mixed reporting system at both organisational and individual levels, which prevents us from exploring further mechanisms of the effect. Nevertheless, the study has provided important evidence for further improving the reporting system.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that PR interventions reduced the incidence of oral antibiotic prescription and slowed down the increase of combined use of antibiotics for URTIs. However, this effect is limited. Overall, the use of antibiotics remained at high levels, and the PR interventions failed to make an influence on the frequent use of injections and infusions as an administration route. The impact of PR interventions is dependent upon pressures from consumers, payers, managers, and colleagues. Patient empowerment mechanisms, financial incentives, reliable information systems, consumer education, and prescriber buy-in are required to maximise the impact of PR interventions.

Abbreviations

- DID:

-

Difference-in-difference

- HIS:

-

Health information system

- IV:

-

Intravenous injection

- NCMS:

-

New Cooperative Medical Scheme

- PR:

-

Public reporting

- TOPSIS:

-

Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution

- URTIs:

-

Upper respiratory tract infections

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization.

References

Li Y: China’s misuse of antibiotics should be curbed. BMJ. 2014, 348: g1083-10.1136/bmj.g1083.

Dong L, Yan H, Wang D: Drug prescribing indicators in village health clinics across 10 provinces of Western China. Fam Pract. 2011, 28 (1): 63-67. 10.1093/fampra/cmq077.

Reynolds L, McKee M: Factors influencing antibiotic prescribing in China: an exploratory analysis. Health Policy. 2009, 90 (1): 32-36. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.09.002.

Swartz MN: Use of antimicrobial agents and drug resistance. New Engl J Med. 1997, 337 (7): 491-492. 10.1056/NEJM199708143370709.

Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Gerding DN, Weinstein RA, Burke JP, Huskins WC, Paterson DL, Fishman NO, Carpenter CF, Brennan PJ, Billeter M, Hooton TM, Infectious Diseases Society of America; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America: Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 44 (2): 159-177. 10.1086/510393.

Quach C, Weiss K, Moore D, Rubin E, McGeer A, Low DE: Clinical aspects and cost of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in children: resistant vs. susceptible strains. Int J Antimicrob Ag. 2002, 20 (2): 113-118. 10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00127-9.

Butler CC, Hood K, Kinnersley P, Robling M, Prout H, Houston H: Predicting the clinical course of suspected acute viral upper respiratory tract infection in children. Fam Pract. 2005, 22 (1): 92-95.

Ashworth M, Latinovic R, Charlton J, Cox K, Rowlands G, Gulliford M: Why has antibiotic prescribing for respiratory illness declined in primary care? A longitudinal study using the general practice research database. J Public Health (Oxf). 2004, 26 (3): 268-274. 10.1093/pubmed/fdh160.

Scottish Medicines Consortium Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group: Prudent Antimicrobial use in Primary Care – Respiratory (Paper 13). 2009, Glasgow: Scottish Medicines Consortium

Petersen I, Johnson AM, Islam A, Duckworth G, Livermore DM, Hayward AC: Protective effect of antibiotics against serious complications of common respiratory tract infections: retrospective cohort study with the UK General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2007, 335 (7627): 982-10.1136/bmj.39345.405243.BE.

Arroll B: Antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Respir Med. 2005, 99 (3): 255-261. 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.11.004.

Arroll B, Kenealy T: Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005, 3: D247-

Hrisos S, Eccles M, Johnston M, Francis J, Kaner EF, Steen N, Grimshaw J: An intervention modelling experiment to change GPs' intentions to implement evidence-based practice: using theory-based interventions to promote GP management of upper respiratory tract infection without prescribing antibiotics #2. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008, 8: 10-10.1186/1472-6963-8-10.

The State Council of China: Implementation Plan for the Recent Priorities of the Health Care System Reform (2009–2011).http://www.china.org.cn/government/scio-press-conferences/2009-04/09/content_17575401.htm,

Yang L, Liu C, Ferrier JA, Zhou W, Zhang X: The impact of the National Essential Medicines Policy on prescribing behaviours in primary care facilities in Hubei province of China. Health Policy Plan. 2013, 28 (7): 750-760. 10.1093/heapol/czs116.

Ketelaar NABM, Faber MJ, Flottorp S, Rygh LH, Deane KHO, Eccles MP: Public release of performance data in changing the behaviour of healthcare consumers, professionals or organisations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, 11: CD004538-

Fung CH, Lim Y, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG: Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148 (2): 111-123. 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00006.

Mannion R, Davies HT: Reporting health care performance: learning from the past, prospects for the future. J Eval Clin Pract. 2002, 8 (2): 215-228. 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2002.00331.x.

Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH: The public release of performance data: what do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. JAMA. 2000, 283 (14): 1866-1874. 10.1001/jama.283.14.1866.

Leatherman S, McCarthy D: Public disclosure of health care performance reports: experience, evidence and issues for policy. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999, 11 (2): 93-98. 10.1093/intqhc/11.2.93.

Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Davies HT, Smith PC: Public reporting on quality in the United States and the United Kingdom. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003, 22 (3): 134-148. 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.134.

Mukamel DB, Haeder SF, Weimer DL: Top-down and bottom-up approaches to health care quality: the impacts of regulation and report cards. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014, 35: 477-497. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-082313-115826.

Lansky D: Improving quality through public disclosure of performance information. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002, 21 (4): 52-62. 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.52.

Frølich A, Talavera JA, Broadhead P, Dudley RA: A behavioral model of clinician responses to incentives to improve quality. Health Policy. 2007, 80 (1): 179-193. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.03.001.

McNamara P: Provider-specific report cards: a tool for health sector accountability in developing countries. Health Policy Plann. 2006, 21 (2): 101-109. 10.1093/heapol/czj009.

Hwang C, Lai Y, Liu T: A new approach for multiple objective decision making. Comput Oper Res. 1993, 20 (8): 889-899. 10.1016/0305-0548(93)90109-V.

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M: Does publicizing hospital performance stimulate quality improvement efforts?. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003, 22 (2): 84-94. 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.84.

Yip W, Powell-Jackson T, Chen W, Hu M, Fe E, Hu M, Jian W, Lu M, Han W, Hsiao WC: Capitation combined with pay-for-performance improves antibiotic prescribing practices in rural China. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014, 33 (3): 502-510. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0702.

Chakraborty A, Roy S, Loeffler J, Chaves RL: Comparison of the pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of daptomycin in healthy adult volunteers following intravenous administration by 30 min infusion or 2 min injection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009, 64 (1): 151-158. 10.1093/jac/dkp155.

Chen M, Wang L, Chen W, Zhang L, Jiang H, Mao W: Does economic incentive matter for rational use of medicine? China’s experience from the essential medicines program. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014, 32 (3): 245-255. 10.1007/s40273-013-0068-z.

Pratter MR: Cough and the common cold: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006, 129 (1 Suppl): 72S-74S.

Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del MC: Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, 11: D23-

Glasziou PP, Del MC, Sanders SL, Hayem M: Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004, 1: D219-

Abegunde D: Inefficiencies due to Poor Access to and Irrational Use of Medicines to Treat Acute Respiratory Tract Infections in Children. 2010, Geneva: World Health Organization

Hu S: Essential medicine policy in China: pros and cons. J Med Econ. 2013, 16 (2): 289-294. 10.3111/13696998.2012.751176.

Werner RM, Asch DA: The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information. JAMA. 2005, 293 (10): 1239-1244. 10.1001/jama.293.10.1239.

Vaiana ME, McGlynn EA: What cognitive science tells us about the design of reports for consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2002, 59 (1): 3-35. 10.1177/1077558702059001001.

Schneider EC, Epstein AM: Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. JAMA. 1998, 279 (20): 1638-1642. 10.1001/jama.279.20.1638.

Chinese Ministry of Health: Survey Report of Chinese Health Literacy. 2009, Beijing

Marshall MN, Romano PS, Davies HTO: How do we maximize the impact of the public reporting of quality of care?. Int J Qual Health C. 2004, 16: I57-I63. 10.1093/intqhc/mzh013.

Liu C, Bartram T, Casimir G, Leggat SG: The link between Participation in Management Decision-making and Quality of Patient Care as Perceived by Chinese Doctors. Public Manage Rev. 2014, In print

Liu C, Liu W, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Wang P: Patient safety culture in China: a case study in an outpatient setting in Beijing. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014, 23: 556-564. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002172.

Sherman KL, Gordon EJ, Mahvi DM, Chung J, Bentrem DJ, Holl JL, Bilimoria KY: Surgeons’ perceptions of public reporting of hospital and individual surgeon quality. Med Care. 2013, 51 (12): 1069-1075. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000013.

Mukamel DB, Glance LG, Dick AW, Osler TM: Measuring quality for public reporting of health provider quality: making it meaningful to patients. Am J Public Health. 2010, 100 (2): 264-269. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153759.

Ledikwe JH, Grignon J, Lebelonyane R, Ludick S, Matshediso E, Sento BW, Sharma A, Semo BW: Improving the quality of health information: a qualitative assessment of data management and reporting systems in Botswana. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014, 12: 7-10.1186/1478-4505-12-7.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks go to managers of the participating organisations. We are grateful to the support from the local governments. Shiru Yang, Xin Du, Xiaopeng Zhang, and Yuqing Tang participated in data collection. Adamm Ferrier provided editorial review.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.71373092). The funding body plays no roles in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XZ made substantial contributions to the project design, acquisition, and interpretation of data. LY made contributions to the study design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. CL made significant contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. LW and XY participated in the acquisition and interpretation of data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the article and agreed to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Liu, C., Wang, L. et al. Public reporting improves antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in primary care: a matched-pair cluster-randomized trial in China. Health Res Policy Sys 12, 61 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-12-61

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-12-61