Abstract

Background

Endometrial function is essential for embryo implantation. The aim of this study was to analyze gene expression profiles from individual endometrial samples obtained from women with repeated implantation failure after IVF in oocyte donation programs.

Methods

Seventeen volunteers were recruited: women who had previously participated as recipients in oocyte donation cycles and repeatedly exhibited implantation failure (Group A, study group, n = 5) or had at least one successful cycle (Group B, control group, n = 6) and spontaneously fertile women (Group C, normal fertility group, n = 6). An endometrial cycle was induced with exogenous estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P) and an endometrial sample was collected on the seventh day of P treatment.

Results

Transcriptome analysis showed 82 genes with consistent differential gene expression when comparing A vs. B and A vs. C. One hundred transcripts differentially expressed in group A vs. B have been shown to be regulated by P, suggesting compromised P signaling in the endometrium. The P receptor (PR) mutation PROGINS was not detected in women from group A. Semi-quantitation of immunoreactive PRA/B, PRB and Sp1 (a transcription factor related to P signaling) in paraffin-embedded endometrial sections, did not show statistically significant differences amongst groups. However immunostaining glycodelin was significantly decreased in endometrial samples from group A

Conclusions

We conclude that some cases of repeated implantation failure could be associated with an aberrant gene expression profile. Compromised P signaling might be the underlying mechanism for such endometrial gene expression deregulation in women with repeated implantation failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cellular and molecular events in the uterine milieu that lead to successful blastocyst implantation are required in the endometrium to become receptive and ready for implantation. Acquisition of receptivity is driven by estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P), which acting through their receptors, change the transcription rate of target genes [1]. Particularly, the postovulatory rise in P triggers a sequence of highly coordinated responses beginning with the detention of the estrogen-induced epithelial cell proliferation and followed by the transformation to a secretory phenotype of the gland, recruitment of leukocytes and angiogenesis [2]. The P action is mediated primarily through binding to and activation of its cognate receptors; the full length B- and N-terminally truncated A isoforms of the P receptor (PR), classically defined as ligand-activated transcription factors [3]. Upon exposure to P, the ligand-activated receptor can directly interact with specific P-response elements (PREs) in the promoter regions of target genes. It is accepted that P acts on an estrogen primed endometrium to initiate a pattern of gene expression important for achievement of receptivity and an altered PR signaling has been associated with human endometrial dysfunction [4]. The antiprogestin mifepristone binds to the PR with high affinity blocking the biological effects of P. In women, the administration of a single dose of oral mifepristone (200 mg) during the secretory phase of the cycle rapidly renders the endometrium unreceptive and modifies gene expression in the uterus within 6 h of administration [5–7].

The development of microarray technology has led to many large-scale gene expression profiling studies of human endometrium [8–10]. Although there seems to be very few consensus genes that have been identified across similar studies [11], collectively they demonstrate that a multitude of genes are associated with the endometrial transcriptome, whose regulation for the acquisition of the receptive phenotype is ultimately driven by P. The approach our group has used to identify the endometrial receptivity transcript profile in a previous report from our laboratory [12] was to analyze endometrial tissue obtained from women during a mock hormonal treatment cycle for oocyte donation as a recipient. The endometrial samples are collected during the time interval corresponding to the window of implantation [13] comparing gene expression profiles from women who were refractory to implantation and those who achieved pregnancy in previous oocyte donation cycles [12]. Although this previous study provided interesting insights to endometrial gene expression associated with implantation failure, the microarrays analysis was performed with only 3(from a total of 5) samples from women with repeated embryo implantation failure that were pooled and using a microarrays platform that examined only one-third of the human genome; providing only a partial view of the whole picture.

The aim of the present report was to examine the individual gene expression profiles in the endometrium from women with implantation failure and compare them with those obtained from fertile women in order to identify compromised transcripts and pathways in the infertile group. We used a microarrays platform for complete coverage of the human genome and bioinformatics tools for data interpretation. Here we report that several transcripts, whose expression level is aberrant in the infertile group, have been described as regulated by P and are related to immune function.

Methods

Subjects

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Investigations in Human Beings of Faculty of Medicine, University of Chile: protocol No. 093–2008, approved 12-29-2008, initiated 01-05-2009 finished 03-31-2014. Each volunteer participating read and signed the informed consent approved by the respective Ethics Review Committee.

Three groups of women were recruited as has been described elsewhere [12]. Group A (n = 5) consisted of women that had never been pregnant and had previously participated in two or more cycles as recipients in an oocyte donation program with no evidence of embryo implantation. Male partners had normal seminal parameters and transferred embryos had good morphology, at least equivalent to embryos transferred to the oocyte donor who became pregnant. Since good quality embryos with the ability to implant and develop normally derive from good quality oocytes, it was required that the oocyte donor had become pregnant from the same oocyte pool. Women from group A were recruited within 3 years following the last failed cycle. Group B (n = 6) comprised of women who became pregnant as recipients in previous oocyte donation cycles and delivered live infants. Group C (n = 6) included normal fertile women who conceived in natural cycles and had three or more live births and had elective tubal ligation at least 1 year prior to their participation for reasons unrelated to this study. Women from groups B and C were recruited within 5 years following the last successful pregnancy. The general exclusion criteria for all volunteers included: metabolic or endocrine diseases other than those leading to ovarian failure, chronic use of medication other than HRT, polycystic ovary syndrome, drug abuse, obesity, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease and current genital tract infection. Age and body mass index from recruited women as well as the plasma P and endometrial thickness measured on the day of the endometrial collection are shown in Table 1.

Induction of endometrial cycle

All subjects underwent the induction of an artificial endometrial cycle with exogenous ethinyl E2 for 20 days and for the last 7 days, this treatment was administered concomitantly with micronized P as described previously [12]. An endometrial sample was obtained on 20th day of the endometrial cycle. One part of the specimen was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at -80 ° C until use and the remaining portion was fixed in paraformaldehyde for histological dating, according to the criteria of Noyes et al., [14] and for immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies. All biopsies were classified as normal secretory endometrium with no signs of inflammatory processes.

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA was extracted from frozen endometrial tissue samples using Trizol (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) as directed by the manufacturer and then checked for yield and quality as described before [12]. The Human Genome U133 plus 2.0 GeneChip oligonucleotide microarrays (Affymetrix, Sunnyvale, CA, USA); corresponding to 47,000 transcripts and variants, including 38,500 well-characterized human genes, was used for gene expression analysis according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Microarrays Data Analysis: Replicate hybridizations were performed for each RNA sample and raw data obtained from the GeneChip Microarray Suite v 1.4 was subsequently analyzed using the National Cancer Institute’s Microarrays Data Base webtool (mAdb) (http://nciarray.nci.nih.gov).

Statistical analyses of microarrays data

Significant genes were defined as ≥2, p-value < 0.001 and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.1 [15]. T-test was performed to determine statistical differences and from the significant genes identified, Venn diagrams were constructed to identify coincident transcripts.

Hierarchical clustering

Was performed based on uncentered correlations with average linkage clustering using mAdb. The resulting dendogram allows data structure visualization of endometrial samples according to total gene expression, revealing samples with similar patterns of gene expression and relationships between the specimens.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

Was performed for simplifying the large amount of data derived from microarray analysis [16]. We applied the unbiased PCA algorithm to all samples using all transcripts analyzed with the microarray chip to look for expression patterns and underlying cluster structures of endometrial samples.

Functional clustering

To increase the effectiveness of DNA microarray analysis, data sets of differentially expressed genes from the comparison between A vs. B and A vs. C were intersected to define those transcripts consistently up- or down-regulated and combined with external data sources, such as gene annotation, in order to associate the expression patterns of this particular set of genes with the biological processes that they may represent. In our analysis, we submitted our gene lists to the web-based tools DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) [17] and GATHER (Gene Annotation Tool to Help Explain Relationships) [18] for functional annotation analysis in order to gain an in-depth understanding of their biological themes, which otherwise would require laborious and somewhat subjective manual literature searches.

DAVID

Up- and down-regulated genes were submitted to DAVID database for systematically extracting biological meaning for them by retrieving pathway maps from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [19] and Biocarta pathways database (http://www.biocarta.com/genes/index.asp) along with Gene Ontology (GO) functional annotations from Entrez Gene [20]. The parameters of the “Functional Annotation Clustering” (a part of the “Functional Annotation Tool”) were set to the highest level of stringency in order to obtain the smallest number of maps. The DAVID database associates each annotation to a gene group using a contingency table representation and calculates its significance.

GATHER

Regulated genes were submitted as well to GATHER database (http://gather.genome.duke.edu/) that contains the GO annotations and KEGG pathways. The GATHER database associates each group of transcripts with the same functional annotation and calculates a Bayes factor [18] which is a measure of the strength of the evidence supporting an association of an annotation with the submitted gene list. We have selected a low Bayes factor (≥3) for presenting the preponderant evidences for associations.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

A portion of each endometrial sample was fixed in paraformaldehyde, included in paraffin blocks and 5 μm sections were prepared. PR-A/B, PR-B, glycodelin and Specificity protein 1 (Sp1) were evaluated by IHC in the endometrial samples using the antibodies and dilutions shown in Table 2 and the broad spectrum Histostain-SP kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as described previously [21]. Immunoreactive PRA/B, PRB, Sp1 and glycodelin in endometrial sections was semi-quantified using the expression level score (ELS), calculated by means of Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics Rockville, MD, USA) as described previously [21]. Briefly, ELS = Mean Optical Density of immunostaining x Percent Area Positively Stained x 100.

DNA isolation and PROGINSdetection

Genomic DNA was isolated from leukocytes derived from peripheral blood obtained by venipuncture using the PAXgene Blood DNA Validation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The detection of Alu insertion in intron G and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis in exon 5 to confirm the presence of PROGINS mutation was performed as described by Pisarska et al. [23].

Results

Gene expression profile analysis

Women with implantation failure (group A, n = 5), women with 2 or more livebirths conceived either by oocyte donation (group B, n = 6) or naturally (group C, n = 6) were subjected to an oocyte donation mock cycle as recipients and on the seventh day of P administration an endometrial sample was obtained. Total RNA was extracted from each tissue sample and used to individually probe the HG_U133 plus 2.0 human gene microarray comprising of 54,675 genes and expressed sequence tags.

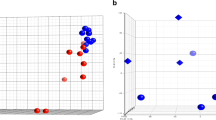

We performed PCA for all the endometrial samples analyzed using their respective gene expression profiles for their representation on a three-dimensional graphic (Figure 1A). Each point in a PCA graph represents the gene expression profile of an endometrial sample and the distance between two plotted points is proportional to the degree of similarity between the gene expression profiles. The PCA plot comprising of a projection on the first three principal components, which together explain 48.8% (21%, 14%, and 13%) of the total variance, showed that endometrial samples from infertile subjects clustered apart from samples belonging to the control groups. In addition, gene expression profiles from endometrial samples obtained from microarray analysis were subjected to unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis in order to generate a dendogram, which is a tree-structured graph that illustrates the similarities in gene expression profiles between endometrial samples from all groups. The dendogram obtained displayed a striking segregation of samples into two major clustering branches, corresponding to the implantation failure group (Group A) and the successful implantation groups (Groups B and C, Figure 1B).

Principal component analysis (PCA) plot of gene expression profiles from endometrial samples and Venn diagrams from differentially expressed transcripts. A, The profiles from infertile women (group A (n = 5); red dots) cluster separately to clusters representative of women with embryo implantation (groups B (n = 6) and C (n = 6); green and blue dots, respectively). B, hierarchical clustering analysis represented in a tree-like dendogram revealing the similarities on gene expression profiles of endometrial samples. A clear segregation of samples into two major clustering branches, one with samples from group A and the other with samples form groups B and C that self-cluster together. C, Venn diagrams showing the differentially expressed genes in each group, which are either 2-fold down- (panel C) or up-regulated (panel D) in endometrial samples from women with implantation failure (group A) compared to those from women that conceived either by IVF (Group B) or naturally (group C).

The microarrays data analysis revealed that 747 transcripts were down-regulated in group A compared to group B; whereas 218 transcripts were up-regulated (Figure 1C and 1D). When group A was compared to group C, 156 and 884 transcripts were decreased and increased respectively in group A (Figure 1C and 1D). Only 31 and 51 transcripts down- and up-regulated respectively were common when comparing group A with the control groups B and C (Figure 1C and 1D). The lists of common differentially expressed genes in the comparison of gene expression profiles from group A vs. Group B and Group A vs. group C is in Table 3 for down- and Table 4 for up-regulated transcripts. An independent validation by Real Time RT-PCR for some of the differentially expressed genes found in the samples used in this study has been reported elsewhere [12], supporting our microarrays findings.

Functional associations of transcripts dysregulated in group A vs. control groups

In order to gain further understanding of the potential functional roles of dysregulated endometrial transcripts from group A, we obtained the functional annotations from each gene and determined the enriched processes associated to them from two different web-based tools. Within the down-regulated transcripts, the functional classifications immune response and complement activation, classical pathway were found to be statistically over-represented using the web based applications DAVID and GATHER respectively (p < 0.01). The Bayes factor obtained with the analysis using the GATHER database was 3, which indicates that the association of this particular function with the total of the transcripts in our gene list is weak. The up-regulated transcript list was not enriched with transcripts related to a particular function.

P-regulated genes in women with implantation failure (group A) vs. control (group B)

We reasoned that the endometrium of women from group A might have a dysregulation in P-regulated transcripts as it has been described for endometriosis and also these genes might be coincident with those whose expression in the endometrium is altered upon treatment with the PR antagonist mifepristone. Since women from groups A and B only differ on the embryo implantation outcome, the list of dysregulated transcripts in group A vs. group B during the receptive phase of the endometrium was selected. Within this repertoire, we searched for those genes known to be regulated in normal cycling endometrium by P as it has been described before [4]. For that we accounted for those transcripts that, directed by P, get regulated for the acquisition of endometrial receptivity [24–32] and/or dysregulated in conditions that render the endometrium with an unreceptive phenotype (i.e., endometriosis and mifepristone treatment) and that intersected with our list of up and down regulated genes (i.e., A vs. B). We considered only those that had the opposite regulation compared with receptive endometrium, and same regulation in endometrium from women with compromised P signaling in the endometrium such as treated with mifepristone [7] and/or from women with endometriosis [4]. We found 14 and 86 up- and down-regulated genes respectively in the endometrium during the receptive period of women with implantation failure vs. control group B (Tables 5 and 6).

PROGINS detection

Since the comparative gene expression analysis of P-regulated genes in endometrial samples from group A, suggested an altered P response, we determined the presence of the Alu insertion in intron G of the PR gene (PROGINS) in women from groups A, B and C. Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis was also carried out on exon 5 of PR gene for confirmation. We found 4 heterozygous subjects for pgr (Figures 2A and B). Two were from group B and two from group C, whereas no PROGINS alleles were detected in women from group A.

Screening for PROGINS allele. A, identification of Alu insertion in Intron G. The Alu insertion in the progesterone receptor gene generates a 494-bp PCR product compared to the 174-bp fragment obtained for the wild type. Samples 04, 05, 24 and 25 with bands at 494 bp and 174 bp indicate the presence of PROGINS in the heterozygous state. All the other lanes with a single fragment of 174 bp indicate the presence of the wild-type progesterone receptor in the homozygous state. B, restriction digestion of exon 5 with NlaIII. Lanes for samples 04, 05, 24 and 25 confirm the presence of PROGINS in heterozygous state; NlaIII cleaves the PCR product into two fragments, 106 and 53 bp. All the other samples displayed the uncleaved 159-bp fragment only, indicating the presence of the wild type receptor.

IHC analysis

Since the levels of both isoforms of PR in human endometrium have been found to be abnormal in patients with endometriosis [33, 34], we evaluated the immunoreactive presence of PR-A/B (Figures 3A and 3C), PR-B (Figures 3D and 3F) along with Sp1 (Figure 3G and 3I) and the P-regulated glycoprotein glycodelin (Figures 3 J and 3L) in paraformaldehyde-fixed paraffin embedded endometrial tissue from groups A, B and C by IHC. Immunostaining was semi-quantified by calculating the respective ELS scores for each detected molecule in all groups of women (Figure 4). ELS for glycodelin in groups B and C was 10.6 and 12.1 fold from group A respectively (p = 0.00509, Figure 4A). The presence of PR-A/B and PR-B in endometrial tissue was evaluated (Figures 3A-C and 3D-F, respectively), since a possible post-translational dysregulation of PR expression (not detected by transcript analysis) might explain the differential gene expression of P-regulated genes in the endometrium from women of group A such as glycodelin. The ELS scores obtained for PR-A/B and PRB did not show significant differences amongst groups (Figures 4B and 4C respectively). In addition, semi-quantitation of immunoreactive Sp1, a known co-activator and trans-activator of the PR that mediates P-induced glycodelin expression, did not show significant differences amongst groups A, B and C (Figure 4D).

Immunodetection of progesterone receptor (A and B isoforms, PR), progesterone receptor B (PRB), Specificity Protein 1 (Sp1) and glycodelin in endometrial sections. Representative photomicrographs of endometrial sections immunostained in triplicate for PR (panels A, B and C), PRB (panels D, E and F), Sp1 (panels G, H and I) and glycodelin (panels J, K and L) are shown in women from group A (panels A, D, G and J; n = 5), group B (panels B, E, H and K; n = 6) and group C (panels C, F, I and L; n = 6).

Immunohistochemistry semiquantitation. Expression Level Score (ELS) for immunostaining of glycodelin (panel A), PRA/B (panel B), PRB (panel C) and Sp1 (panel D) in endometrial sections from groups A (n = 5), B (n = 6) and C (n = 6). Data is expressed as average ELS ± SD for each group. *p < 0.05, Kruskal Wallis U-test.

Discussion

Uterine receptivity is defined as a restricted time-related period when the uterus is receptive to blastocyst attachment and implantation. The establishment of this endometrial transition, which supports embryo implantation, is primarily coordinated by ovarian hormones, E2 and P that modulate uterine events in a spatiotemporal manner.

Endometrial factors, at the molecular level, have been suggested to explain some cases of infertility, recurrent miscarriages and implantation failure after IVF. In the present study we assessed the endometrial gene expression profile during the receptive period in mock oocyte donation cycles of women with repeated embryo implantation failure (Group A). Their profiles were compared with those obtained from women who achieved embryo implantation and pregnancy in oocyte donation cycles (Group B), or which got pregnant in natural spontaneous cycles (Group C). The data suggest a strong association between an aberrant endometrial gene expression and implantation failure. The stimulation protocol with steroid hormones performed before the endometrial sample collection was the same for all participating women in this study. Hence, the differential transcript profile in Group A suggests a long-term dysregulation of endometrial gene regulation rendering it not suitable for embryo implantation. The functional annotation analysis of dysregulated transcripts showed an enrichment of decreased genes involved in immune response and complement activation in women with repeated implantation failure.

Integration and cross-validation of endometrial transcripts regulated by P could increase the confidence in expression results for many more genes than is tractable with classical one-by-one validation of differentially expressed genes and should provide the up- and down-regulated genes that together orchestrate the acquisition of the receptive phenotype of the endometrium for embryo implantation. Such exploration and integration could help to get a comprehensive view of existing data needed to better prioritize experimental efforts. We identified a subset of P-regulated transcripts with differential expression in the endometrium of women from group A compared to the control group B revealing compromised P-signalling in the endometrium.

Pisarska et al. [23] reported that 42% of women with unexplained infertility carry the allele for the PROGINS mutation compared with 14% of control fertile women (with at least 1 term pregnancy). We analyzed the presence of the PROGINS allele in women from groups A, B and C and found no correlation between the PROGINS carrier women and altered transcript levels of P-regulated genes in the endometrium. This result is in line with a study from Coulam et al. [35] that did not find an association between PR polymorphisms with recurrent implantation failure in women after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer.

Glycodelin, encoded by the gene PAEP [36, 37] is the main P-regulated glycoprotein secreted by the endometrial epithelium during the secretory phase and early pregnancy [38]. The transcript levels for PAEP have also been consistently identified to be one of the most abundant in the endometrium by several gene expression profiling studies [24, 25, 27, 31], and it has been shown to be decreased in women with endometriosis [39]. In the present study we found that the transcript levels for PAEP were decreased in the endometrium of women from group A compared to both control groups (Table 5). In addition, immunoreactive glycodelin evaluation in endometrial sections showed the protein to be significantly decreased in group A which is in line with the microarrays data. These results are consistent with the reduced concentrations of glycodelin in uterine flushing reported for patients with unexplained infertility [40]. In normal ovulatory cycles, P secretion is followed by endometrial glycodelin synthesis in epithelial glands from 4 to 5 postovulatory days onwards [37, 41]. Endometrial epithelial cells stimulated in vitro with progestins showed an increase in glycodelin transcription, synthesis, and secretion [42] however a PR-antagonist failed to prevent the induction of glycodelin [43]. In silico analysis of PAEP gene promoter sequence identified a potential P response element [44], however functional studies found that the transcription factor Sp1 mediates the effect of P and PR on human glycodelin expression in endometrial cells [45]. We semiquantified the immunoreactive levels of PR-A/B, PR-B and Sp1 in endometrial sections of women from groups A, B and C and found no significant differences between the groups.

The endometrial response to the increased circulating levels of P during the luteal phase has shown to be remarkably different in women with endometriosis compared to healthy controls. Such response has been evidenced by dysregulated specific gene networks of P-dependent genes in patients with endometriosis compared to non-diseased patients in eutopic secretory endometrium [4, 39, 46, 47]. This transcriptional behavior has led to the concept of ‘P resistance’ which may explain the association between pelvic endometriosis and infertility. We have found that the endometrial transcript profile from women with repeated implantation failure (group A) presents altered gene expression profile including several transcripts reported to be P-regulated, suggesting a women from group A have a compromised P signalling in the endometrium.

The cause of this endometrial defect is unknown, although the apparent intrinsic dysregulation in P signalling that renders the endometrium unreceptive in women with repeated embryo implantation failure seems to be beyond perturbations in PR expression such as chaperone proteins involved in receptor recycling and ligand binding [48], coregulators [49–51], as well as associated transcription factors and a variety of upstream signal transduction pathways capable of modifying PR and its coregulators [52–56]. In addition, the action of the P is not limited to the cell type in which is PR expressed since steroid hormone regulation can be mediated also through epithelial-stromal cross talk in the endometrium [57]. Also P can elicit a variety of rapid signalling events, independently of a direct transcriptional regulation or even in the absence of its cognate nuclear receptors [58] which may modulate gene expression. The molecular mechanism behind the defect in P-regulated gene networks in the endometrium of women with repeated embryo implantation failure is yet to be determined.

Conclusions

We conclude that some cases of repeated implantation failure could be associated with an aberrant gene expression profile, particularly of transcripts related to the immune function and complement activation. Compromised P signaling might be the underlying mechanism for such endometrial gene expression deregulation in women with repeated implantation failure. Future research should focus on determining the causes of incomplete P signalling in the endometrium from these women.

Abbreviations

- DAVID:

-

Database for annotation visualization and integrated discovery

- E2:

-

Estradiol

- ELS:

-

Expression level score

- GATHER:

-

Gene annotation tool to help explain relationships

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- mAdb:

-

National cancer institute’s microarrays data base webtool

- P:

-

Progesterone

- PAEP:

-

Progestagen-associated endometrial protein

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- Pgr :

-

Progesterone receptor gene

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- PR-A/B:

-

Progesterone receptor isoforms A and B

- PR-B:

-

Progesterone receptor isoform B

- PREs:

-

Progesterone-response elements

- PROGINS:

-

Alu insertion in intron G of the progesterone receptor gene

- RFLP:

-

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription coupled to polymerase chain reaction

- Sp1:

-

Specificity Protein 1..

References

O’Malley BW, Tsai MJ: Molecular pathways of steroid receptor action. Biol Reprod. 1992, 46: 163-167. 10.1095/biolreprod46.2.163.

Gellersen B, Brosens IA, Brosens JJ: Decidualization of the human endometrium: mechanisms, functions, and clinical perspectives. Semin Reprod Med. 2007, 25: 445-453. 10.1055/s-2007-991042.

Beato M: Gene regulation by steroid hormones. Cell. 1989, 56: 335-344. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90237-7.

Burney RO, Talbi S, Hamilton AE, Vo KC, Nyegaard M, Nezhat CR, Lessey BA, Giudice LC: Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2007, 148: 3814-3826. 10.1210/en.2006-1692.

Hapangama DK, Critchley HO, Henderson TA, Baird DT: Mifepristone-induced vaginal bleeding is associated with increased immunostaining for cyclooxygenase-2 and decrease in prostaglandin dehydrogenase in luteal phase endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87: 5229-5234. 10.1210/jc.2002-020429.

Danielsson KG, Marions L, Bygdeman M: Effects of mifepristone on endometrial receptivity. Steroids. 2003, 68: 1069-1075. 10.1016/S0039-128X(03)00131-4.

Catalano RD, Critchley HO, Heikinheimo O, Baird DT, Hapangama D, Sherwin JR, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith SK, Sharkey AM: Mifepristone induced progesterone withdrawal reveals novel regulatory pathways in human endometrium. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007, 13: 641-654. 10.1093/molehr/gam021.

Horcajadas JA, Pellicer A, Simon C: Wide genomic analysis of human endometrial receptivity: new times, new opportunities. Hum Reprod Update. 2007, 13: 77-86.

Ruiz-Alonso M, Blesa D, Simon C: The genomics of the human endometrium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1822, 2012: 1931-1942.

Haouzi D, Dechaud H, Assou S, De Vos J, Hamamah S: Insights into human endometrial receptivity from transcriptomic and proteomic data. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012, 24: 23-34. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.09.009.

Tapia A, Vilos C, Marin JC, Croxatto HB, Devoto L: Bioinformatic detection of E47, E2F1 and SREBP1 transcription factors as potential regulators of genes associated to acquisition of endometrial receptivity. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011, 9: 14-10.1186/1477-7827-9-14.

Tapia A, Gangi LM, Zegers-Hochschild F, Balmaceda J, Pommer R, Trejo L, Pacheco IM, Salvatierra AM, Henriquez S, Quezada M, Vargas M, Ríos M, Munroe DJ, Croxatto HB, Velasquez L: Differences in the endometrial transcript profile during the receptive period between women who were refractory to implantation and those who achieved pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2008, 23: 340-351.

Damario MA, Lesnick TG, Lessey BA, Kowalik A, Mandelin E, Seppala M, Rosenwaks Z: Endometrial markers of uterine receptivity utilizing the donor oocyte model. Hum Reprod. 2001, 16: 1893-1899. 10.1093/humrep/16.9.1893.

Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J: Dating the endometrial biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975, 122: 262-263.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Statist Soc Ser B (Method). 1995, 57: 289-300.

Joliffe IT, Morgan BJ: Principal component analysis and exploratory factor analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 1992, 1: 69-95. 10.1177/096228029200100105.

Dennis G, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA: DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003, 4: P3-10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-p3.

Chang JT, Nevins JR: GATHER: a systems approach to interpreting genomic signatures. Bioinformatics. 2006, 22: 2926-2933. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl483.

Kanehisa M, Goto S, Hattori M, Aoki-Kinoshita KF, Itoh M, Kawashima S, Katayama T, Araki M, Hirakawa M: From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34: D354-357. 10.1093/nar/gkj102.

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G: Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Gene Ontology Consortium Nat Genet. 2000, 25: 25-29.

Gonzalez-Ramos R, Rocco J, Rojas C, Sovino H, Poch A, Kohen P, Alvarado-Diaz C, Devoto L: Physiologic activation of nuclear factor kappa-B in the endometrium during the menstrual cycle is altered in endometriosis patients. Fertil Steril. 2012, 97: 645-651. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.12.006.

Koistinen H, Koistinen R, Dell A, Morris HR, Easton RL, Patankar MS, Oehninger S, Clark GF, Seppala M: Glycodelin from seminal plasma is a differentially glycosylated form of contraceptive glycodelin-A. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996, 2: 759-765. 10.1093/molehr/2.10.759.

Pisarska MD, Carson SA, Casson PR, Tong X, Buster JE, Kieback DG: A mutated progesterone receptor allele is more prevalent in unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril. 2003, 80: 651-653. 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00755-6.

Kao LC, Tulac S, Lobo S, Imani B, Yang JP, Germeyer A, Osteen K, Taylor RN, Lessey BA, Giudice LC: Global gene profiling in human endometrium during the window of implantation. Endocrinology. 2002, 143: 2119-2138. 10.1210/endo.143.6.8885.

Borthwick JM, Charnock-Jones DS, Tom BD, Hull ML, Teirney R, Phillips SC, Smith SK: Determination of the transcript profile of human endometrium. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003, 9: 19-33. 10.1093/molehr/gag004.

Carson DD, Lagow E, Thathiah A, Al-Shami R, Farach-Carson MC, Vernon M, Yuan L, Fritz MA, Lessey B: Changes in gene expression during the early to mid-luteal (receptive phase) transition in human endometrium detected by high-density microarray screening. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002, 8: 871-879. 10.1093/molehr/8.9.871.

Riesewijk A, Martin J, van Os R, Horcajadas JA, Polman J, Pellicer A, Mosselman S, Simon C: Gene expression profiling of human endometrial receptivity on days LH + 2 versus LH + 7 by microarray technology. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003, 9: 253-264. 10.1093/molehr/gag037.

Mirkin S, Arslan M, Churikov D, Corica A, Diaz JI, Williams S, Bocca S, Oehninger S: In search of candidate genes critically expressed in the human endometrium during the window of implantation. Hum Reprod. 2005, 20: 2104-2117. 10.1093/humrep/dei051.

Talbi S, Hamilton AE, Vo KC, Tulac S, Overgaard MT, Dosiou C, Le Shay N, Nezhat CN, Kempson R, Lessey BA, Nayak NR, Giudice LC: Molecular phenotyping of human endometrium distinguishes menstrual cycle phases and underlying biological processes in normo-ovulatory women. Endocrinology. 2006, 147: 1097-1121. 10.1210/en.2005-1076.

Ace CI, Okulicz WC: Microarray profiling of progesterone-regulated endometrial genes during the rhesus monkey secretory phase. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004, 2: 54-10.1186/1477-7827-2-54.

Haouzi D, Mahmoud K, Fourar M, Bendhaou K, Dechaud H, De Vos J, Reme T, Dewailly D, Hamamah S: Identification of new biomarkers of human endometrial receptivity in the natural cycle. Hum Reprod. 2009, 24: 198-205.

Diaz-Gimeno P, Horcajadas JA, Martinez-Conejero JA, Esteban FJ, Alama P, Pellicer A, Simon C: A genomic diagnostic tool for human endometrial receptivity based on the transcriptomic signature. Fertil Steril. 2011, 95: 50-60. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.063. 60 e51-15

Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Yin P, Imir G, Utsunomiya H, Attar E, Innes J, Julie Kim J: Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: link to failure to metabolize estradiol. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006, 248: 94-103. 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.041.

Attia GR, Zeitoun K, Edwards D, Johns A, Carr BR, Bulun SE: Progesterone receptor isoform A but not B is expressed in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 85: 2897-2902.

Coulam CB, Jeyendran RS, Roussev R: Association of progesterone receptor polymorphisms with recurrent implantation failure after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008, 25: 119-122. 10.1007/s10815-008-9210-9.

Seppala M, Bohn H, Tatarinov Y: Glycodelins. Tumour Biol. 1998, 19: 213-220. 10.1159/000030009.

Seppala M, Taylor RN, Koistinen H, Koistinen R, Milgrom E: Glycodelin: a major lipocalin protein of the reproductive axis with diverse actions in cell recognition and differentiation. Endocr Rev. 2002, 23: 401-430. 10.1210/er.2001-0026.

Bell SC, Hales MW, Patel S, Kirwan PH, Drife JO: Protein synthesis and secretion by the human endometrium and decidua during early pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985, 92: 793-803. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb03048.x.

Kao LC, Germeyer A, Tulac S, Lobo S, Yang JP, Taylor RN, Osteen K, Lessey BA, Giudice LC: Expression profiling of endometrium from women with endometriosis reveals candidate genes for disease-based implantation failure and infertility. Endocrinology. 2003, 144: 2870-2881. 10.1210/en.2003-0043.

Mackenna A, Li TC, Dalton C, Bolton A, Cooke I: Placental protein 14 levels in uterine flushing and plasma of women with unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril. 1993, 59: 577-582.

Seppala M, Koistinen H, Koistinen R, Chiu PC, Yeung WS: Glycosylation related actions of glycodelin: gamete, cumulus cell, immune cell and clinical associations. Hum Reprod Update. 2007, 13: 275-287. 10.1093/humupd/dmm004.

Taylor RN, Vigne JL, Zhang P, Hoang P, Lebovic DI, Mueller MD: Effects of progestins and relaxin on glycodelin gene expression in human endometrial cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000, 182: 841-847. 10.1016/S0002-9378(00)70333-4. discussion 847–849

Taylor RN, Savouret JF, Vaisse C, Vigne JL, Ryan I, Hornung D, Seppala M, Milgrom E: Promegestone (R5020) and mifepristone (RU486) both function as progestational agonists of human glycodelin gene expression in isolated human epithelial cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998, 83: 4006-4012.

Vaisse C, Atger M, Potier B, Milgrom E: Human placental protein 14 gene: sequence and characterization of a short duplication. DNA Cell Biol. 1990, 9: 401-413. 10.1089/dna.1990.9.401.

Gao J, Mazella J, Seppala M, Tseng L: Ligand activated hPR modulates the glycodelin promoter activity through the Sp1 sites in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001, 176: 97-102. 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00450-6.

Aghajanova L, Velarde MC, Giudice LC: Altered gene expression profiling in endometrium: evidence for progesterone resistance. Semin Reprod Med. 2010, 28: 51-58. 10.1055/s-0029-1242994.

Taylor HS, Bagot C, Kardana A, Olive D, Arici A: HOX gene expression is altered in the endometrium of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 1999, 14: 1328-1331. 10.1093/humrep/14.5.1328.

Hirota Y, Tranguch S, Daikoku T, Hasegawa A, Osuga Y, Taketani Y, Dey SK: Deficiency of immunophilin FKBP52 promotes endometriosis. Am J Pathol. 2008, 173: 1747-1757. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080527.

Aghajanova L, Velarde MC, Giudice LC: The progesterone receptor coactivator Hic-5 is involved in the pathophysiology of endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2009, 150: 3863-3870. 10.1210/en.2009-0008.

Caballero V, Ruiz R, Sainz JA, Cruz M, Lopez-Nevot MA, Galan JJ, Real LM, de Castro F, Lopez-Villaverde V, Ruiz A: Preliminary molecular genetic analysis of the Receptor Interacting Protein 140 (RIP140) in women affected by endometriosis. J Exp Clin Assist Reprod. 2005, 2: 11-10.1186/1743-1050-2-11.

Suzuki A, Horiuchi A, Oka K, Miyamoto T, Kashima H, Shiozawa T: Immunohistochemical detection of steroid receptor cofactors in ovarian endometriosis: involvement of down-regulated SRC-1 expression in the limited growth activity of the endometriotic epithelium. Virchows Arch. 2010, 456: 433-441. 10.1007/s00428-010-0884-x.

Kim JJ, Taylor HS, Lu Z, Ladhani O, Hastings JM, Jackson KS, Wu Y, Guo SW, Fazleabas AT: Altered expression of HOXA10 in endometriosis: potential role in decidualization. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007, 13: 323-332. 10.1093/molehr/gam005.

Lee B, Du H, Taylor HS: Experimental murine endometriosis induces DNA methylation and altered gene expression in eutopic endometrium. Biol Reprod. 2009, 80: 79-85. 10.1095/biolreprod.108.070391.

Shazand K, Baban S, Prive C, Malette B, Croteau P, Lagace M, Racine JB, Hugo P: FOXO1 and c-jun transcription factors mRNA are modulated in endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004, 10: 871-877. 10.1093/molehr/gah119.

Wu Y, Halverson G, Basir Z, Strawn E, Yan P, Guo SW: Aberrant methylation at HOXA10 may be responsible for its aberrant expression in the endometrium of patients with endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005, 193: 371-380. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.034.

Yang S, Fang Z, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Zhou J, Gurates B, Tamura M, Ferrer K, Bulun S: Regulation of aromatase P450 expression in endometriotic and endometrial stromal cells by CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (C/EBPs): decreased C/EBPbeta in endometriosis is associated with overexpression of aromatase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87: 2336-2345.

Cunha GR, Cooke PS, Kurita T: Role of stromal-epithelial interactions in hormonal responses. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004, 67: 417-434. 10.1679/aohc.67.417.

Gellersen B, Fernandes MS, Brosens JJ: Non-genomic progesterone actions in female reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2009, 15: 119-138.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge to all volunteer women participating in the present study for their generous contribution. Also we acknowledge Dr. Fernando Gabler for dating the endometrial samples, Dr. H. Koistinen for providing the glycodelin antibody and Felipe Argandona for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by FONDECYT 11100443 / 1140614 and FONDAP 15010006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AT conceived the study, participated in its design, carried out the microarrays and bioinformatic analyses and helped to draft the manuscript. PF and JB participated in PROGINS detection. J.C.M participated in PROGINS detection, data analysis and interpretation. D.J.M. participated in microarrays analysis. HBC conceived the study, participated in its design, data interpretation and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tapia-Pizarro, A., Figueroa, P., Brito, J. et al. Endometrial gene expression reveals compromised progesterone signaling in women refractory to embryo implantation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 12, 92 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-12-92

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-12-92