Abstract

Background

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is an uncommon and highly aggressive malignancy with undetermined histogenesis and poor prognosis. To date, no case of testicular DSRCT has been reported in the literature.

Case

A 42-year-old Chinese man presented with painless swelling of his left testis and a painless palpable nodule in his left inguinal region. Computed tomography showed a solid mass in the left testis and multiple metastases in the body. Laboratory tests gave no abnormal results. Left radical orchiectomy was performed, and histopathological and molecular pathological examination showed typical features of DSRCT. Six cycles of chemotherapy were administrated after the operation, leading to partial remission. Postoperative 9-month follow-up indicated no progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is an extremely rare malignancy with undetermined histogenic origin. To date, about 300 cases have been reported in the literature, since it was first described as a mesenchymal entity with distinct clinicopathological features by Gerald and Rosai in 1989[1, 2]. DSRCT is prone to develop in adolescents and young adults, and the incidence in males is more than three times that in females[3]. The majority of DSRCTs originate from the abdominal cavity and pelvis, thus the retroperitoneum, omentum, and mesentery are often involved, in addition to multiple peritoneal tumors[4]. Although rarer, invasion of extraperitoneal sites, such as the central nervous system, nasal sinus, lung, bone and soft tissues, kidney, ovary and paratesticular region, has been documented[5–11]. However, no DSRCT derived from testis has been reported to date. Herein, we report a case of solid neoplasm in testis that was confirmed pathologically to be testicular DSRCT.

Case presentation

A 42-year-old Chinese man was admitted to the Department of Urology at our hospital, with an 8-month history of painless swelling of his left testis and a 6-month history of a painless palpable nodule in his left inguinal region. He had no relevant personal or family history of malignancy.

On physical examination, an egg-size solid lump was found in the left testis, and a palpable, slightly mobile, solid nodule, 2 × 3 cm in size, in the left inguinal region. Laboratory tests, including α-fetoprotein, β-human chorionic gonadotropin, and lactate dehydrogenase, gave no abnormal results. Computed tomography (CT) showed a confined solid mass, 2 × 3 cm in size with homogenous attenuation in the left testis, and multiple lesions in the right diaphragmatic crus, retroperitoneal region, and peritoneal and pelvic cavity, in the left inguinal region, and in the near-bilateral iliac vessels, suggestive of multiple metastases (Figure 1). In addition, the patient’s left renal pelvis and ureter were dilated.

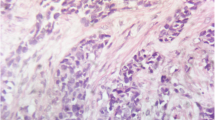

The preoperative diagnosis was left testicular tumor with multiple metastases. Left radical orchiectomy was carried out, and the cut surface of the tumor showed fish-like changes. Histopathological examination of the resected specimen revealed a malignant tumor composed of well-defined nests of small round blue cells, which were separated by abundant desmoplastic stroma (Figure 2). The spermatic cord and epididymis were also involved. Immunohistochemical evaluation exhibited the following: Cytokeratin Pan (+), Epithelial Membrane Antigen (+),Cytokeratin 7(−), vimentin (+), desmin (+) (Figure 3), Inhibin (−/+), Chromogranin A (weakly +), synaptophysin (+/−), CD56 (−), Placental ALK. Phosphatase (−/+),Wilm’s Tumor-1 (WT-1) protein (−), Myogenin (−/+), MyoD1 (−) and Neuron-specific enolase (+). Molecular evidence of t(11;22) (p13;q12) was detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). Based on the abovementioned evidence, a diagnosis of testicular DSRCT was confirmed (pT3 N2 M1 S0).

The patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day in a good condition. In the third postoperative week, he was readmitted to the Department of Oncology at our hospital and received the VAC multi-agent systemic chemotherapy regimen consisting of vincristine (2 mg, day 1), adriamycin (75 mg/m2, day 1) and cyclophosphamide (1.2 g/m2, day 1). After six cycles of chemotherapy, the patient was appraised as being in partial remission. Postoperative 9-month follow-up indicated no progression as measured by CT assessment (Figure 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first case with testicular DSRCT documented in the literature. DSRCT has a male predominance and occurs most frequently in the second to third decades of life[3]. As it can have delitescent onset without apparent symptoms and is highly aggressive, DSRCT is often diagnosed at a relatively advanced stage. Furthermore, owing to the paucity of this tumor, there is no optimal treatment strategy and favorable long-term survival have not been achieved.

The diagnosis of DSRCT remains challenging. Because most DSRCTs are found in the abdominal cavity, some non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and pain) and a palpable abdominal mass, are the main problems leading to patients visiting a doctor. If present in extraperitoneal sites, DSRCT can cause specific symptoms, mostly owing to expansion and compression of the tumor. Weight loss, acratia, ascites, and cachexia may occur when there is tumor dissemination or extensive lymphogenous and hematological metastases. In our case, the patient was in good general condition when he visited his doctor, but multiple metastases had already developed. The tumor features, such as non-specific manifestations and high aggression, meant that the patient was already experiencing late-stage disease at his first visit.

Imaging methods can help to detect DSRCT, although there are no typical characteristics. CT scans show homogenous low attenuation with modest uniform enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT in small masses, while central low attenuation with modest heterogeneous enhancement on post-contrast CT, suggestive of central hemorrhage or necrosis, may be observed in cases of larger masses[12]. In addition, calcification is relatively common. Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging also reveal one or multiple nodules ‘studding‘ the peritoneal cavity or other locations[13]. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT is recommended as an effective evaluation of tumor staging[14]. In a retrospective study, Arora et al. evaluated the role of fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT for diagnosis of DSRCT, and found an accurate detection of 97.4% of all DSRCTs, with sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of 96.1%, 98.6%, 98.0%, and 97.1%, respectively[12]. Recently, fine-needle aspiration cytology has been tried, and found to provide another effective approach for early diagnosis and chemotherapeutic response assessment of DSRCT[15].

Microscopically, DSRCT consists of well-defined nests of small round blue cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and indistinct nucleoli, which are separated by affluent desmoplastic stroma. Peripheral palisading of tumor cells and rosette-like structures may be observed[1, 16]. Immunohistochemistry demonstrates divergent differentiation of DSRCT, which can be used as a definite diagnostic marker for DSRCT. The tumor stains positivelhy for several epithelial (e.g. keratin), mesenchymal (e.g. vimentin), myogenic (e.g. desmin), and neural (e.g. CD56) markers, thus desmin and vimentin together produce a unique staining pattern, namely the punctuate and perinuclear cytoplasmic positivity, which is a notable trait of DSRCT[16]. C19, an antibody to the C-terminal region of the WT1 protein, has been proven useful for differentiating DSRCT from Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (EWS/PNET) when genetic information is unavailable[17]. The presence of the specific cytogenetic abnormality t(11;22)(p13;q12) is observed in more than 90% of all patients[18], which eventually promotes uncontrolled proliferation of DSRCT cells[19]. Several staging systems have been suggested for classification of peritoneal malignancies[20], but no validated staging system has been proposed for DSRCT. Recently, a new staging system based on the Peritoneal Cancer Index was proposed, by which comparison of DSRCT outcomes may be applied, although this was carried out with only a small cohort of patients and needs further validation[21]. In our case, we used the staging system established by UICC[22] in 2002 for testicular tumor, because no other available staging systems were suitable for this rare case.

In general, DSRCT must be distinguished from other small round cell tumors, such as EWS/PNET, neuroblastoma, and lymphoma. Similarly to DSRCT, EWS/PNET is also composed of small round cells in sheets or nests. Typically, EWS/PNET is positive for CD99 and vimentin, and negative for cytokeratins and myogenic markers. Different from DSRCT, which has a translocation of t (11;22)(p13;q12), EWS/PNET has a characteristic reciprocal chromosomal translocation of t(11;22)(q24;q12)[16]. Neuroblastoma often occurs in children. Tumor cells are negative for CK, WT1 and desmin, and the stroma is rich in nerve fiber network, with ganglion cell differentiation commonly observed[23]. High-grade lymphoma may share similar histologic features with DSRCT, however, lymphomas often display a diffuse growth pattern. Positive lymphoid markers and negative epithelial and myogenic markers can help with the differential diagnosis[24].

Currently, no consensus has been made as to the treatment protocols for DSRCT[25]. Debulking surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are possible therapeutic strategies, although none of them appears to have better efficacy than the others. Debulking surgery is still the main approach of DSRCT management. In a retrospective study, a 3-year survival rate of 58% was reported for patients who received debulking surgery, whereas no patients in the non-surgical group survived for more than 3 years[26]. Although DSRCT is somewhat sensitive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, durable remissions remain rare[27]. Chemotherapeutic agents commonly administrated for DSRCT include doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, ifosfamide and etoposide. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has been performed in some institutions[28, 29], and the 3-year survival in patients receiving debulking surgery with HIPEC was 71%, compared with 62% in patients who underwent surgery alone; however this did not reach statistical significance[17]. Radiotherapy is helpful in prolonging life but does not promote long-term survival[1].

Generally speaking, the prognosis of DSRCT is poor. A median progression-free survival of 2.6 years was reported by Schwarz et al., and another study group reported that 71% of patients died within a mean of 25.2 months[30, 31]. Because no standard therapeutic strategy has been recommended, we administrated the VAC protocol to our patient after debulking surgery, following the treatment for sarcoma, and there was no progression appeared at the postoperative 9-month follow-up. However, the patient requires further observation due to the follow-up time.

Conclusions

DSRCT is a relatively uncommon and highly aggressive tumor, with poor prognosis. The diagnosis is usually established by immunohistochemistry. To date, no standard treatment protocol has been proposed. More investigations are warranted to define the optimal therapeutic strategy.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- DSRCT:

-

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

- EWS:

-

Ewing sarcoma

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FISH:

-

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

- HIPEC:

-

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PNET:

-

primitive neuroectodermal tumor

- WT-1:

-

Wilm’s tumor1.

References

Zhang J, Xu H, Ren F, Yang Y, Chen B, Zhang F: Analysis of clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Pathol Oncol Res. 2013, 20: 161-168.

Ji TH, Deng J, Zhang ZG, Yu YH, Liu QH, Zeng L: Pathological features of desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Chin J Oncol. 2003, 63: 579-

Gerald WL, Ladanyi M, De Alava E, Cuatrecasas M, Kushner BH, LaQuaglia MP, Rosai J: Clinical, pathologic, and molecular spectrum of tumors associated with t(11;22)(p13;q12): desmoplastic small round-cell tumor and its variants. J Clin Oncol. 1998, 16: 3028-3036.

Gerald WL, Miller HK, Battifora H, Miettinen M, Silva EG, Rosai J: Intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round-cell tumor. Report of 19 cases of a distinctive type of high-grade polyphenotypic malignancy affecting young individuals. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991, 15: 499-513.

Neder L, Scheithauer BW, Turel KE, Arnesen MA, Ketterling RP, Jin L, Moynihan TJ, Giannini C, Meyer FB: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the central nervous system: report of two cases and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2009, 454: 431-439.

Lopez F, Costales M, Vivanco B, Fresno MF, Suarez C, Llorente JL: Sinonasal desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013, 40: 573-576.

Syed S, Haque AK, Hawkins HK, Sorensen PH, Cowan DF: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002, 126: 1226-1228.

Adsay V, Cheng J, Athanasian E, Gerald W, Rosai J: Primary desmoplastic small cell tumor of soft tissues and bone of the hand. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999, 23: 1408-1413.

Su MC, Jeng YM, Chu YC: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004, 28: 1379-1383.

D’Ippolito G, Huizing MT, Tjalma WA: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) arising in the ovary: report of a case diagnosed at an early stage and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2012, 33: 96-100.

Thuret R, Renaudin K, Leclere J, Battisti S, Bouchot O, Theodore C: Uncommon malignancies: case 3. Paratesticular desmoplastic small round-cell tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 6253-6255.

Arora VC, Price AP, Fleming S, Sohn MJ, Magnan H, LaQuaglia MP, Abramson S: Characteristic imaging features of desmoplastic small round cell tumour. Pediatr Radiol. 2013, 43: 93-102.

Hayes-Jordan A, Anderson PM: The diagnosis and management of desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a review. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011, 23: 385-389.

Zhang WD, Li CX, Liu QY, Hu YY, Cao Y, Huang JH: CT, MRI, and FDG-PET/CT imaging findings of abdominopelvic desmoplastic small round cell tumors: correlation with histopathologic findings. Eur J Radiol. 2011, 80: 269-273.

Leca LB, Vieira J, Teixeira MR, Monteiro P: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2012, 56: 576-580.

Chang F: Desmoplastic small round cell tumors: cytologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006, 130: 728-732.

Hill DA, Pfeifer JD, Marley EF, Dehner LP, Humphrey PA, Zhu X, Swanson PE: WT1 staining reliably differentiates desmoplastic small round cell tumor from Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor. An immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostic study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000, 114: 345-353.

Yang JL, Xu WP, Wang J, Zhu XZ, Zhang RY: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Chin J Pathol. 2005, 34: 45-50.

Rodriguez E, Sreekantaiah C, Gerald W, Reuter VE, Motzer RJ, Chaganti RS: A recurring translocation, t(11;22)(p13;q11.2), characterizes intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round-cell tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1993, 69: 17-21.

Harmon RL, Sugarbaker PH: Prognostic indicators in peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastrointestinal cancer. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2005, 2: 3-

Hayes-Jordan A, Green H, Fitzgerald N, Xiao L, Anderson P: Novel treatment for desmoplastic small round cell tumor: hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion. J Pediatr Surg. 2010, 45: 1000-1006.

Sobin LH, Wittekind C: UICC: TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 2002, Wiley-Liss, 6

Li M, Cai MY, Lu JB, Hou JH, Wu QL, Luo RZ: Clinicopathological investigation of four cases of desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Oncol Lett. 2012, 4: 423-428.

Devoe K, Weidner N: Immunohistochemistry of small round-cell tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000, 17: 216-224.

Dufresne A, Cassier P, Couraud L, Marec-Berard P, Meeus P, Alberti L, Blay JY: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: current management and recent findings. Sarcoma. 2012, 2012: 714986-

Lal DR, Su WT, Wolden SL, Loh KC, Modak S, La Quaglia MP: Results of multimodal treatment for desmoplastic small round cell tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2005, 40: 251-255.

Kushner BH, LaQuaglia MP, Wollner N, Meyers PA, Lindsley KL, Ghavimi F, Merchant TE, Boulad F, Cheung NK, Bonilla MA, Crouch G, Kelleher JF, Steinherz PG, Gerald WL: Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor: prolonged progression-free survival with aggressive multimodality therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1996, 14: 1526-1531.

Hayes-Jordan A, Anderson P, Curley S, Herzog C, Lally KP, Green HL, Hunt K, Mansfield P: Continuous hyperthermic peritoneal perfusion for desmoplastic small round cell tumor. J Pediatr Surg. 2007, 42: E29-E32.

Msika S, Gruden E, Sarnacki S, Orbach D, Philippe-Chomette P, Castel B, Sabate JM, Flamant Y, Kianmanesh R: Cytoreductive surgery associated to hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion for desmoplastic round small cell tumor with peritoneal carcinomatosis in young patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2010, 45: 1617-1621.

Schwarz RE, Gerald WL, Kushner BH, Coit DG, Brennan MF, La Quaglia MP: Desmoplastic small round cell tumors: prognostic indicators and results of surgical management. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998, 5: 416-422.

Ordonez NG: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: I: a histopathologic study of 39 cases with emphasis on unusual histological patterns. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998, 22: 1303-1313.

Acknowledgement

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GMZ and YZ conceived of the concept, and participated in drafting the manuscript. HLG reviewed the pathological slides and revised the manuscript. DWY supervised the project and revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Gui-Ming Zhang, Yao Zhu contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, GM., Zhu, Y., Gan, HL. et al. Testicular desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a case report and review of literature. World J Surg Onc 12, 227 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-227

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-227