Abstract

Background

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is a rare autosomal dominantly inherited connective tissue disorder with an estimated prevalence of 1:5,000. More than 1000 variants have been previously reported to be associated with MFS. However, the disease-causing effect of these variants may be questionable as many of the original studies used low number of controls. To study whether there are possible false-positive variants associated with MFS, four in silico prediction tools (SIFT, Polyphen-2, Grantham score, and conservation across species) were used to predict the pathogenicity of these variant.

Results

Twenty-three out of 891 previously MFS-associated variants were identified in the ESP. These variants were distributed on 100 heterozygote carriers in 6494 screened individuals. This corresponds to a genotype prevalence of 1:65 for MFS. Using a more conservative approach (cutoff value of >2 carriers in the EPS), 10 variants affected a total of 82 individuals. This gives a genotype prevalence of 1:79 (82:6494) in the ESP. A significantly higher frequency of MFS-associated variants not present in the ESP were predicted to be pathogenic with the agreement of ≥3 prediction tools, compared to the variants present in the ESP (p = 3.5 × 10−15).

Conclusions

This study showed a higher genotype prevalence of MFS than expected from the phenotype prevalence in the general population. The high genotype prevalence suggests that these variants are not the monogenic cause of MFS. Therefore, caution should be taken with regard to disease stratification based on these previously reported MFS-associated variants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Marfan syndrome (MFS; OMIM 154700), first described by Antoine Marfan in 1898, is an autosomal dominantly inherited connective tissue disorder with a phenotype that involves mainly the cardiovascular, ocular, and skeletal systems. The prevalence of MFS in the general US and European population has been estimated to be 1:5,000 [1, 2]. MFS has a high penetrance, but variable expression [3]. Cardiovascular complications are the main cause of premature death among MFS patients [4, 5]. Besides aortic aneurysm and/or dissection, MFS can lead to valvular heart disease [6], enlargement of the proximal pulmonary artery [7], congestive heart failure [8], and arrhythmias [9].

According to the current “revised Ghent nosology”, the diagnosis of MFS should be based on clinical manifestation, family history, and molecular genetic testing of the fibrillin 1 gene (FBN1 gene) and the clinical criteria employs a set of manifestations in many tissues [10]. Approximately 25% of all MFS patients do not have a family history and hence, represents new cases due to de novo mutations [3]. To date, more than 1000 variants have been reported to be associated with MFS [11]. Recently, transforming growth factor beta (TGFB) has been found to play a pivotal role in the progression of MFS [12]. A disease that has many similarities with Marfan syndrome, termed Loeys-Dietz syndrome, was identified to be caused by variants in the transforming growth factor-beta type II receptor (TGFBR2) [13]. An atypical or incomplete MFS has also been described in some patients caused by genetic variants in transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor (TGFBR1) and TGFBR2[14]. However, to our knowledge, there are no systematic studies focusing on separating genetic noise from disease-causing variations by identifying variants previously associated with MFS in large-scale populations.

Until recently, there has only been little knowledge regarding the distribution of genetic variations in general population, especially with regard to low-frequency variants of MFS. This is potentially a problem, when rare variants are associated with MFS because of the risk of false-positive findings. The disease-causing role of some of these variants is questionable as many of these studies have used low number of controls. This problem has now partly been solved with the release of exome data from the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Large-scale surveys of human genetic variations provide an important chance to identify causative variants, notable for an excess of rare genetic variants [15].

The aim of this study was to identify false positive variants previously associated with Marfan syndrome. This is important since genetic testing today is used in order to confirm MFS diagnose according to the revised Ghent Nosology. In the absence of family history and aortic root dilatation/dissection, but presence of ectopialentis, the identification of an FBN1 variant previously associated with aortic disease is required in making the diagnosis. Also in the absence of family history and ectopialentis, but presence of aortic root dilatation/dissection a genetic test for identification of mutation in FBN1 is sufficient to establish a MFS diagnosis. Due to the importance of a positive genetic finding in patients suspected of MFS, identification of false positive variants has major clinical implications. Furthermore, we aimed to provide comprehensive in silico prediction analysis to all MFS-associated variants, in order to better classify the impact of the variations on the encoded proteins.

Methods

In the ESP, next-generation sequencing was carried out for all protein-coding regions in 6,503 individuals from different population studies [16]. It currently contains 2,203 unrelated African-Americans (AA) and 4,300 unrelated European-Americans (EA) (13,006 alleles in total). In the ESP database, samples were selected to contain healthy controls, the extremes of specific traits (LDL and blood pressure), and specific diseases (early onset myocardial infarction and early onset stroke), and lung diseases. To our knowledge, patients with MFS have not been included intentional in ESP. Clinical data were not available, nor on request.

To find all genes and variants associated with MFS, a search for missense and nonsense variants was performed in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD Professional 2013.2) [17]. Additionally, the following literature search query was used in the PubMed database ((Marfan) OR (Marfan syndrome) or (“Marfan syndrome” [Mesh])) AND ((Genetic) OR (“Genetics” [Mesh])) AND ((mutation) OR (variant)). In this way, we included 3 variants recently associated with MFS [18–20]. Finally, we searched the ESP for all these variants (Version: v.0.0.20. (June 7, 2013)). We used a terminology so that MFS-associated variants identified in the ESP database are termed ESP-Positive variants and variants not identified in ESP as ESP-Negative variants. Because of lack of data regarding introns and untranslated regions in the ESP, variants in introns and untranslated regions could not be included. Furthermore, we did not include variants in the genes COL1A2 and LTBP2, since variants in these genes have not been convincingly associated with MFS. Since the aim of this study was to include all possible variants previously associated with MFS, we also included variants which were associated with MFS using the old Ghent criteria.

Based on the phenotype prevalence of MFS (1/5000 = 0.02%), the expected prevalence of MFS in the ESP population is 0.02% (95% CI 0.0%-0.05%) for 1.3 subjects out of 6503.

Therefore, estimated number of individuals affected by MFS in the ESP can be expected to be no more than 2. That is, a given variant with complete penetrance should theoretically not affect more than 2 ESP alleles in order to be the cause of a monogenic form of MFS. For a conservative approach, we therefore used a cutoff value of >2 affected the ESP alleles, to estimate the genotype prevalence of MFS.

The literature was searched for functional data and familial co-segregation of all the MFS-associated ESP-Positive variants. Familial co-segregation was defined as at least two family members having the same genotype as well as the same MFS phenotype.

Four traditional prediction tools (SIFT,Polyphen-2, Grantham score, and conservation across species) were applied in order to predict the pathogenicity of all MFS-associated missense variants. Nonsense variants that were assumed “probably damaging” were not included in the prediction analyses. Missense variants were classified as damaging if they were predicted to be damaging by ≥3 of the four applied prediction tools [21]. Conservation across species of sequence indicates that a particular genotype have been preserved during the evolution. For more detail, please see online Additional file 1. The list of ESP-Negative variants is shown in the Additional file 2: Table S1. Any difference in the proportion of variants predicted to be damaging for ESP-Positive variants compared with ESP-Negative variants was assessed with the Fisher’s exact. A two-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered statistical significant.

Results

Variants associated with MFS

Three genes have been previously reported to be involved in MFS: FBN1, TGFBR1, and TGFBR2. In FBN1, TGFBR1, and TGFBR2, a total of 891 missense/nonsense variants have been reported to be associated with MFS. There are737missense and 154 nonsense variants associated with MFS. Overall, 97% (861/891) of all variants were found in FBN1, less than 3% (26/891) and less than 1% (4/891) was found in TGFBR2and TGFBR1, respectively.

The ESP-positive variants

Twenty-three out of the 891 variants previously associated with MFS were identified in the ESP population. All of the 23ESP-positive variants were missense variants found in the FBN1 gene, and 87% (20/23) of these variants have been reported as novel mutations in the published original papers. In total, 100 heterozygote carriers of these 23variants were present in the ESP. The FBN1 gene was screened in 6,494 individuals on average in the ESP. This corresponds to a genotype prevalence of 1:65 (100:6494) in the ESP (Table 1). This is a very large overrepresentation of MFS associated variants; hence, it is likely that many of these variants are not the major/monogenic cause of MFS.

Using a more conservative approach (cutoff value of >2 present in the EPS), 10 out of the 23 variants were present in three or more individuals in the ESP. These variants affected a total of 82 individuals giving a genotype prevalence of 1:79 (82:6494). The remaining 13 variants are rare non-synonymous variants (<=2), affecting 18 individuals in the ESP, giving a genotype prevalence of 1:361 (18:6494) (Table 1).

Among all FBN1 MFS-associated variants, only 3% (23/861) were present in the ESP. Family co-segregation and functional characterization data of all the 23 variants are present in Table 2. Most of MFS-associated variants were ESP-Negative variants. None of MFS- associated variants in TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 was identified in the ESP population. Furthermore, clinical data for these 23 patients is shown in Additional file 3: Table S2.

In order to test if the ESP data harbored an over representation, one variant TGFBR2 V387M (rs35766612), previously reported to be involved in the patient with Marfanoid features [36], was genotyped in our own healthy Northern European control population (n = 704). There were 30 carriers of this variant in 6504 individuals on average in the ESP population. We found 4 carriers in our healthy population. The genotype prevalence of the variant in our healthy control population was comparable with that in the ESP (4:750 vs.30:6503, p = 0.578).

Prediction analyses of the ESP-positive variants vs. the ESP-negative variants

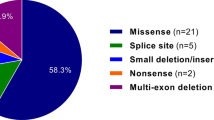

Using SIFT prediction, 26% (6/23) of the ESP-Positive variants were predicted to be damaging, compared with86% (613/713) of the ESP-Negative variants (p = 4.1 × 10−10). Using Polyphen-2 prediction tool, the variants present in the ESP were predicted pathogenic in 39% (9/23) of the cases compared with 94% (670/713) of the ESP-Negative variants (p = 2.8 × 10−11). Using the Grantham scores, 22% (5/23) of the ESP-Positive variants were predicted to be damaging compared with 72% (516/713) of the ESP-Negative variants (p = 1.1 × 10−6). Finally, we used Conservation across species and found that 61% (14/23) of the ESP-Positive variants were identified in a conserved region, predicted as damaging, compared with 92% (659/713) of the ESP-Negative variants (p = 4.5 × 10−5). The calculation of the agreement of ≥3 pathogenicity predictions showed that 13% (3/23) of variants present in the ESP and 88% (627/713) of the ESP-Negative variants were predicted to be damaging (p = 3.5 × 10−15) (Figure 1). For more details, please see the online Additional file 2. Same trend was found when the ESP positive was divided into whether they occurred more or less than two times in the ESP (online Additional file 4: Figure S1).

Percentage of variants predicted to be pathogenic with four In silico tools prediction on variants present and not present in ESP database. Differences in proportions of variants predicted to be damaging for those variants present in ESP versus variants not present in ESP were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. *p = 4.1 × 10−10, **p = 2.8 × 10−11, ***p = 1.1 × 10−6, ****p = 4.5 × 10−5, *****p = 3.5 × 10−15.

Discussion

The present study is the first to report and critically evaluate the genetic background noise in Marfan syndrome based on the prevalence of previously reported MFS-associated genetic variants in the ESP database. We found a much higher prevalence (1:65) of MFS-associated genetic variants in the ESP than expected according to the phenotype prevalence of 1:5,000 in the general US and European population. The ESP data is thought to be representative for this population.

In order to test if the ESP data harbored an over representation, one variantTGFBR2 V387M (rs35766612), previously reported to be involved in the patient with Marfanoid features [36], was genotyped in our own healthy Northern European control population (n = 704). There were 30 carriers of this variant in 6,504 individuals on average in the ESP population. We found 4 carriers in our healthy population. The genotype prevalence of the variant in our healthy control population was comparable with that in the ESP (4:750 vs.30:6503, p = 0.578). For more details, please see the online Additional file 1. Recent papers have also established the prevalence of other rare variants genotyped in our Northern European control population and found that they were comparable to those of the ESP [37–39]. This is suggesting that it is unlikely that the ESP population harbor a major overrepresentation of some of the MFS-associated variants.

A prevalence like this is however unlikely to be caused by reduced penetrance or age-related delayed presentation of the disease, as MFS has a high penetrance with onset of symptoms early in life [3].

It is likely that some of these variants are either not a monogenic cause of MFS, or they have incomplete penetrance. Lucarini et al. [40] screened the TGFBR1 gene in patients with MFS who were excluded as carriers of the variants in FBN1 and TGFBR2. Their findings suggested that some variants are overrepresented in MSF patients compared to control suggesting that TGFBR1 may be the underlying genetic cause of MSF, but with low penetrance alleles in MFS.

Four common prediction tools were applied to evaluate the phylogenetic and physicochemical effects on the MFS-associated variants. Recently published data support the potential clinical utility of these tools [21]. In our study, we found that a much lower proportion of the ESP-Positive variants were predicted to be damaging compared with those ESP-Negative variants (13% vs. 88%, p =3.5 × 10−15, Figure 1). This result further questions the pathogenic role of at least some of the variants present in the ESP. But it does not definitively exclude the possibility of pathogenicity. Some ESP-Positive variants in low frequency could potentially be disease causing. Accordingly, the presence of a variant in the ESP population does not exclude that the variant might be disease-causing, but is indeed questioning the variant disease causing potential, particularly when the variant presents in the ESP in high frequency. The same approach and concerns were recently also suggested in another disease; catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia [41].

We defined a cutoff value (>2) in the ESP (n = 6503) based on the expected prevalence of MFS (1:5,000). This cutoff is of course somewhat arbitrary because we do not know the exact prevalence of MFS in the ESP population. So assuming that MFS is a monogenic disorder, the findings of some variants with prevalence above the cutoff value of more than 2 in the ESP suggest that some of the variants at least may be false-positive, or incomplete penetrance. Reduced or incomplete penetrance is not uncommon in genetic diseases. It can be resulted from differential allelic expression or copy number variation [42]. The interpretation of variants with a prevalence below a certain cutoff value in the ESP may be considered monogenic disease-causing, disease-modifier or benign.

Genetic screening is gaining ground in the diagnostic workup of families and identification of populations at a high risk of suffering an inherited disease [43]. According to “the revised Ghent nosology”, genetic screening for variants may in some cases be the game changer in making the diagnose MFS [10].

Genetic screening for MFS in family members has become an important tool in family cascade screening. In particular, targeted testing of FBN1 is recommended in cases where MFS is suspected following a cardiac examination. It is noteworthy, that only 23 out of 861 (3%) variants in FBN1 were identified in the ESP. That is, 97% of the variants in FBN1were not among nearly 6,500 subjects in the ESP. This confirms the pivotal role and usefulness of the FBN1 gene in genetic screening. Awareness of an FBN1 variant should imply for increased vigilance for MFS. Treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker has been proven to be effective in reducing rates of aortic root dilatation in MFS patients. So knowledge of an FBN-1 variant may allow actionable interventions earlier in the natural history of the condition [5].

Lack of properly scaled control populations has always been a problem when dealing with low frequency genetic variations of rare monogenetic diseases. Without a reasonable control population we might misdiagnose family members undergoing genetic testing and follow-up. Based on our study, we strongly suggest that exome data, like the ESP, should be used as empirical data in research and clinical practice, alongside with known prediction tools to get a more exact understanding of the pathogenicity of the variants associated with MFS or other rare inherited disorders. It is important to keep in mind that the absence of variants in the ESP in itself, is not to be interpreted as the variant is disease causing, but certainly strengthen the possibility. Furthermore the Marfan-related mutations analyses in this study do not exclude that further potentially false-positive variants could be found in healthy persons in other populations such as Asians. Comparing findings in this study with other populations may reduce the rate of false positive variants.

Conclusion

In this study we have identified 23 previously reported MFS-associated variants in the ESP database. The genotype prevalence of these variants corresponded to MFS prevalence of 1:65. The high genotype prevalence questions the causality of some of these variants, suggesting that these variants may not be the monogenic cause of MFS. Therefore, caution should be taken with regard to disease stratification based on variants previously associated with MFS.

References

Arbustini E, Grasso M, Ansaldi S, Malattia C, Pilotto A, Porcu E, Disabella E, Marziliano N, Pisani A, Lanzarini L, Mannarino S, Larizza D, Mosconi M, Antoniazzi E, Zoia MC, Meloni G, Magrassi L, Brega A, Bedeschi MF, Torrente I, Mari F, Tavazzi L: Identification of sixty-two novel and twelve known FBN1 mutations in eighty-one unrelated probands with Marfan syndrome and other fibrillinopathies. Hum Mutat. 2005, 26 (5): 1-15.

Judge DP, Dietz HC: Marfan’s syndrome. Lancet. 2005, 366 (9501): 1965-1976.

Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, Bersin RM, Carr VF, Casey DE, Eagle KA, Hermann LK, Isselbacher EM, Kazerooni EA, Kouchoukos NT, Lytle BW, Milewicz DM, Reich DL, Sen S, Shinn JA, Svensson LG, Williams DM: ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 55 (14): e27-e129.

Schoenhoff FS, Jungi S, Czerny M, Roost E, Reineke D, Matyas G, Steinmann B, Schmidli J, Kadner A, Carrel T: Acute aortic dissection determines the fate of initially untreated aortic segments in Marfan syndrome. Circulation. 2013, 127 (15): 1569-1575.

Barrett PM, Topol EJ: The fibrillin-1 gene: unlocking new therapeutic pathways in cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2013, 99 (2): 83-90.

Lacro RV, Guey LT, Dietz HC, Pearson GD, Yetman AT, Gelb BD, Loeys BL, Benson DW, Bradley TJ, De Backer J, Forbus GA, Klein GL, Lai WW, Levine JC, Lewin MB, Markham LW, Paridon SM, Pierpont ME, Radojewski E, Selamet Tierney ES, Sharkey AM, Wechsler SB, Mahony L: Pediatric Heart Network Investigators: characteristics of children and young adults with Marfan syndrome and aortic root dilation in a randomized trial comparing atenolol and losartan therapy. Am Heart J. 2013, 165 (5): 828-835.

Pati PK, George PV, Jose JV: Giant pulmonary artery aneurysm with dissection in a case of Marfan syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 61 (6): 685-

De Backer JF, Devos D, Segers P, Matthys D, François K, Gillebert TC, De Paepe AM, De Sutter J: Primary impairment of left ventricular function in Marfan syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2006, 112 (3): 353-358.

Halushka MK: Single gene disorders of the aortic wall. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2012, 21 (4): 240-244.

Loeys BL, Dietz HC, Braverman AC, Callewaert BL, De Backer J, Devereux RB, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Jondeau G, Faivre L, Milewicz DM, Pyeritz RE, Sponseller PD, Wordsworth P, De Paepe AM: The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010, 47 (7): 476-485.

Gillis E, Van Laer L, Loeys BL: Genetics of thoracic aortic aneurysm: at the crossroad of transforming growth factor-β signaling and vascular smooth muscle cell contractility. Circ Res. 2013, 113 (3): 327-340.

Sawaki D, Suzuki T: Targeting transforming growth factor-β signaling in Aortopathies in Marfan syndrome. Circ J. 2013, 77 (4): 898-899.

Stheneur C, Collod-Béroud G, Faivre L, Gouya L, Sultan G, Le Parc J-M, Moura B, Attias D, Muti C, Sznajder M, Claustres M, Junien C, Baumann C, Cormier-Daire V, Rio M, Lyonnet S, Plauchu H, Lacombe D, Chevallier B, Jondeau G, Boileau C: Identification of 23 TGFBR2 and 6 TGFBR1 gene mutations and genotype-phenotype investigations in 457 patients with Marfan syndrome type I and II, Loeys-Dietz syndrome and related disorders. Hum Mutat. 2008, 29 (11): E284-E295.

Singh KK, Rommel K, Mishra A, Karck M, Haverich A, Schmidtke J, Arslan-Kirchner M: TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 mutations in patients with features of Marfan syndrome and Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2006, 27 (8): 770-777.

Fu W, O’Connor TD, Jun G, Kang HM, Abecasis G, Leal SM, Gabriel S, Altshuler D, Shendure J, Nickerson DA, Bamshad MJ, Akey JM: Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature. 2013, 493 (7431): 216-220.

Exome Variant Server. Retrieved from: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

Biological Databases for Gene Expression, Pathway & NGS Analysis. Retrieved from: http://www.biobase-international.com/

Dong J, Bu J, Du W, Li Y, Jia Y, Li J, Meng X, Yuan M, Peng X, Zhou A, Wang L: A new novel mutation in FBN1 causes autosomal dominant Marfan syndrome in a Chinese family. Mol Vis. 2012, 18: 81-86.

Van Den Bossche MJA, Van Wallendael KLP, Strazisar M, Sabbe B, Del-Favero J: Co-occurrence of Marfan syndrome and schizophrenia: what can be learned?. Eur J Med Genet. 2012, 55 (4): 252-255.

Hogue J, Lee C, Jelin A, Strecker M, Cox V, Slavotinek A: Homozygosity for a FBN1 missense mutation causes a severe Marfan syndrome phenotype. Clin Genet. 2013, 84 (4): 392-393.

Giudicessi JR, Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Alders M, Salisbury BA, Wilde AAM, Ackerman MJ: Phylogenetic and physicochemical analyses enhance the classification of rare nonsynonymous single nucleotide variants in type 1 and 2 long-QT syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012, 5 (5): 519-528.

Tjeldhorn L, Rand-Hendriksen S, Gervin K, Brandal K, Inderhaug E, Geiran O, Paus B: Rapid and efficient FBN1 mutation detection using automated sample preparation and direct sequencing as the primary strategy. Genet Test. 2006, 10 (4): 258-264.

Rommel K, Karck M, Haverich A, Schmidtke J, Arslan-Kirchner M: Mutation screening of the fibrillin-1 (FBN1) gene in 76 unrelated patients with Marfan syndrome or Marfanoid features leads to the identification of 11 novel and three previously reported mutations. Hum Mutat. 2002, 20 (5): 406-407.

Hung C-C, Lin S-Y, Lee C-N, Cheng H-Y, Lin S-P, Chen M-R, Chen C-P, Chang C-H, Lin C-Y, Yu C-C, Chiu H-H, Cheng W-F, Ho H-N, Niu D-M, Su Y-N: Mutation spectrum of the fibrillin-1 (FBN1) gene in Taiwanese patients with Marfan syndrome. Ann Hum Genet. 2009, 73 (Pt 6): 559-567.

Comeglio P, Johnson P, Arno G, Brice G, Evans A, Aragon-Martin J, da Silva FP, Kiotsekoglou A, Child A: The importance of mutation detection in Marfan syndrome and Marfan-related disorders: report of 193 FBN1 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2007, 28 (9): 928-

Tiecke F, Katzke S, Booms P, Robinson PN, Neumann L, Godfrey M, Mathews KR, Scheuner M, Hinkel GK, Brenner RE, Hövels-Gürich HH, Hagemeier C, Fuchs J, Skovby F, Rosenberg T: Classic, atypically severe and neonatal Marfan syndrome: twelve mutations and genotype-phenotype correlations in FBN1 exons 24–40. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001, 9 (1): 13-21.

Yuan B, Thomas JP, von Kodolitsch Y, Pyeritz RE: Comparison of heteroduplex analysis, direct sequencing, and enzyme mismatch cleavage for detecting mutations in a large gene, FBN1. Hum Mutat. 1999, 14 (5): 440-446.

Hayward C, Porteous ME, Brock DJ: A novel mutation in the fibrillin gene (FBN1) in familial arachnodactyly. Mol Cell Probes. 1994, 8 (4): 325-327.

Mátyás G, De Paepe A, Halliday D, Boileau C, Pals G, Steinmann B: Evaluation and application of denaturing HPLC for mutation detection in Marfan syndrome: Identification of 20 novel mutations and two novel polymorphisms in the FBN1 gene. Hum Mutat. 2002, 19 (4): 443-456.

Liu WO, Oefner PJ, Qian C, Odom RS, Francke U: Denaturing HPLC-identified novel FBN1 mutations, polymorphisms, and sequence variants in Marfan syndrome and related connective tissue disorders. Genet Test. 1997, 1 (4): 237-242.

Collod-Béroud G, Béroud C, Ades L, Black C, Boxer M, Brock DJ, Holman KJ, de Paepe A, Francke U, Grau U, Hayward C, Klein HG, Liu W, Nuytinck L, Peltonen L, Alvarez Perez AB, Rantamäki T, Junien C, Boileau C: Marfan Database (third edition): new mutations and new routines for the software. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26 (1): 229-223.

Sheikhzadeh S, Kade C, Keyser B, Stuhrmann M, Arslan-Kirchner M, Rybczynski M, Bernhardt AM, Habermann CR, Hillebrand M, Mir T, Robinson PN, Berger J, Detter C, Blankenberg S, Schmidtke J, von Kodolitsch Y: Analysis of phenotype and genotype information for the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome. Clin Genet. 2012, 82 (3): 240-247.

Sakai H, Visser R, Ikegawa S, Ito E, Numabe H, Watanabe Y, Mikami H, Kondoh T, Kitoh H, Sugiyama R, Okamoto N, Ogata T, Fodde R, Mizuno S, Takamura K, Egashira M, Sasaki N, Watanabe S, Nishimaki S, Takada F, Nagai T, Okada Y, Aoka Y, Yasuda K, Iwasa M, Kogaki S, Harada N, Mizuguchi T, Matsumoto N: Comprehensive genetic analysis of relevant four genes in 49 patients with Marfan syndrome or Marfan-related phenotypes. Am J Med Genet A. 2006, 140 (16): 1719-1725.

Howarth R, Yearwood C, Harvey JF: Application of dHPLC for mutation detection of the fibrillin-1 gene for the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome in a National Health Service Laboratory. Genet Test. 2007, 11 (2): 146-152.

Milewicz DM, Grossfield J, Cao SN, Kielty C, Covitz W, Jewett T: A mutation in FBN1 disrupts profibrillin processing and results in isolated skeletal features of the Marfan syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1995, 95 (5): 2373-2378.

Mátyás G, Arnold E, Carrel T, Baumgartner D, Boileau C, Berger W, Steinmann B: Identification and in silico analyses of novel TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 mutations in Marfan syndrome-related disorders. Hum Mutat. 2006, 27 (8): 760-769.

Refsgaard L, Holst AG, Sadjadieh G, Haunsø S, Nielsen JB, Olesen MS: High prevalence of genetic variants previously associated with LQT syndrome in new exome data. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012, 20 (8): 905-908.

Risgaard B, Jabbari R, Refsgaard L, Holst A, Haunsø S, Sadjadieh A, Winkel B, Olesen M, Tfelt-Hansen J: High prevalence of genetic variants previously associated with Brugada syndrome in new exome data. Clin Genet. 2013, 84 (5): 489-495.

Andreasen C, Nielsen JB, Refsgaard L, Holst AG, Christensen AH, Andreasen L, Sajadieh A, Haunsø S, Svendsen JH, Olesen MS: New population-based exome data are questioning the pathogenicity of previously cardiomyopathy-associated genetic variants. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013, 21 (9): 918-928.

Lucarini L, Evangelisti L, Attanasio M, Lapini I, Chiarini F, Porciani MC, Abbate R, Gensini G, Pepe G: May TGFBR1 act also as low penetrance allele in Marfan syndrome?. Int J Cardiol. 2009, 131 (2): 281-284.

Jabbari J, Jabbari R, Nielsen MW, Holst AG, Nielsen JB, Haunsø S, Tfelt-Hansen J, Svendsen JH, Olesen MS: New exome data question the pathogenicity of genetic variants previously associated with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013, 6 (5): 481-489.

Cooper DN, Krawczak M, Polychronakos C, Tyler-Smith C, Kehrer-Sawatzki H: Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum Genet. 2013, 132 (10): 1077-1130.

Katsanis SH, Katsanis N: Molecular genetic testing and the future of clinical genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2013, 14 (6): 415-426.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project and its ongoing studies which produced and provided exome variant calls for comparison: the Lung GO Sequencing Project (HL-102923), the WHI Sequencing Project (HL-102924), the Broad GO Sequencing Project (HL-102925), the Seattle GO Sequencing Project (HL-102926) and the Heart GO Sequencing Project (HL-103010).

The work was supported by The Danish Heart Foundation, The Danish National Research Foundation Centre for Cardiac Arrhythmia (DARC), The John and Birthe Meyer Foundation, The Research Foundation at the Heart Centre, Rigshospitalet. National Natural Science Foundation of China [81160027], National Science and Technology Infrastructure Program of China [2013BAI05B10].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

RQY, JJ, XSC, RJ, JBN, BR, XC, AS, JHS, SH, MSO, and JT were involved in the data collection and analysis, and design of the study. RQY, JJ, MSO, and JT carried out the data analysis. JJ carried out statistical calculation. RQY, JJ, JBN, BR, MSO, and JT drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Electronic supplementary material

12863_2013_1263_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: The methods of prediction and genotyping a variant in Northern European control population.(DOCX 17 KB)

12863_2013_1263_MOESM4_ESM.docx

Additional file 4: Figure S1: Percentage of variants predicted to be pathogenic with four In silico tools prediction on variants present and not present in ESP database. Differences in proportions of variants predicted to be damaging for those variants present in ESP versus variants not present in ESP. Furthermore, variants with low frequency (rare non-synonymous variants (<=2)) in the ESP is also shown. (DOCX 117 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, RQ., Jabbari, J., Cheng, XS. et al. New population-based exome data question the pathogenicity of some genetic variants previously associated with Marfan syndrome. BMC Genet 15, 74 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-15-74

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-15-74