Abstract

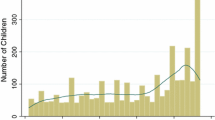

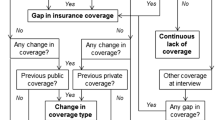

Children living in poverty not only have disproportionately more health problems, but also have disproportionately lower health care service utilization. Change, whether in health care delivery system or in family living situation, may interfere with or jeopardize insurance status and thereby influence access to health care services. We hypothesized that children who have maintained Medicaid insurance compared to those who have not will be more likely to have preventive care visits and less likely to have emergency room visits. We further hypothesized that transient situations such as homeless episodes, foster care placement, and living in more than one location in the same 1-year period will contribute to loss in Medicaid coverage. This retrospective cohort study was conducted at an urban children’s hospital outpatient clinic at which 210 family respondents were recruited over a 1-year period. An in-person interview containing several standardized instruments was administered to the caregiver. In addition, children’s medical records were retrospectively abstracted from point of study entry to first contact. Findings indicated that children who lost Medicaid coverage, compared to others, had significantly fewer preventive care health visits. There were no differences in emergency room visits. Transient situations did not appear to influence preventive or emergency room care. In addition, the change into a managed-care delivery system also increased loss of coverage. Loss of coverage may be a barrier to preventive care services. To ensure optimal preventive care services, the onus is on the providers and plants to facilitate continued insurance coverage.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dubay L, Haley J, Kenney G. Children’s eligibility for Medicaid and SCHIP: a view from 2000. New Federalism National Survey of America’s Families: The Urban Institute; 2002. B1–B7.

Waitzkin H, Williams RL, Bock JA, McCloskey J, Willging C, Wagner W. Safety-net institutions buffer the impact of Medicaid managed care: a multi-method assessment in a rural state. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:598–610.

Newacheck PW, Pearl M, Hughes DC, Halfon N. The role of Medicaid in ensuring children’s access to care. JAMA 1998;280:1789–1793.

Halfon N, Wood DL, Valdez RB, Pereyra M, Duan N. Medicaid enrollment and health services access by Latino children in inner-city Los Angeles. JAMA. 1997;277:636–641.

Medi-Cal Policy Institute. Medi-Cal County Data Book. Oakland, CA: Medi-Cal Policy Institute; 2002.

Soman LA. Testimony to California State Assembly Committee on Health, February 25, 1997, Sacramento, 1997.

Soman LA. Preparing Medi-Cal recipients for managed care: tips for moving into managed care. Child Advocate. 1995;23:4–5.

Soman LA. Testimony to State of California Little Hoover Commission re: status of California’s children in foster care, Milton Marks Commission on California State Government Organization and Economy (State of California Little Hoover Commission), Sacramento, CA, August 9, 2002.

Buesching D, Jablonoski A, Vesta E. Inappropriate emergency room visits. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:672–676.

Center for Health Economics Research. Access to Health Care. Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1993.

Foltin GL. Critical issues in urban emergency medical services for children. Pediatrics. 1995;95:170–178.

O’Brien GM, Stein MD, Zierler S, Shapiro M, O’Sullivan P, Woolard R. Use of the ED as a regular source of care: associated factors beyond lack of health insurance. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:286–291.

Alperstein G, Rappaport C, Flanigtan JM. Health problems of homeless children in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1232–1233.

Bassuk EL, Rubin L, Lauriat A. Characteristics of sheltered homeless families. Am J Public Health. 1986; 6: 1097–1101.

Burg MA. Health problems of sheltered homeless women and their dependent children. Health Soc Work. 1994;19:125–131.

Cunningham PJ, Hahn BA. The changing American future: implications for children’s health insurance coverage and the use of ambulatory care services. The Future of Children 1994;4(3):24–42.

Fowler MG, Simpson GA, Schoendorf KC. Families on the move and children’s health care. Pediatrics. 1993;91:934–940.

Hausman B, Hammen C. Parenting in homeless families: the double crisis. Special section: Homeless women: economic and social issues. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63:358–369.

Rafferty Y, Shinn M. The impact of homelessness on children. Am Psychol. 1991: 46:1170–1179.

Zuckerman B, Parker S. Preventive pediatrics-new models of providing needed health services. Pediatrics, 1995;95:758–762.

Malmström M, Sundquist J, Johansson S-E. Neighborhood environment and selfreported health status: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1181–1186.

Syme SL. Rethinking disease: where do we go from here? Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:463–468.

Macintyre S, Maciver S, Sooman A. Area, class and health: should we be focusing on places or people? J Soc Policy. 1993;22:213–234.

US General Accounting Office. Health Care Shortage Areas: Designations Not a Useful Tool for Directing Resources to the Underserved. Washington, DC; US General Accounting Office; 1995.

Gaston M. Testimony on Safety Net Health Care Programs. Washington, DC: House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, Subcommittee on Human Resources: 1997.

Wright R, Andres T, Davidson A. Finding the medically underserved: a need to revise the federal definition. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1996;7:296–307.

Herrman H, Patrick DL, Diehr P et al., Longitudinal investigation of depression outcomes in primary care in six countries: the LIDO study. Functional status, health service use and treatment of people with depressive symptoms. Psychol Med. 2002;32:889–902.

Lam JA, Rosenheck R. Correlates of improvement in quality of life among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:116–118.

Love L. What makes women tired: a community sample. J Women’s Health. 1998;7:69–76.

Zlotnick C, Gould P. Prenatal quality of life (QOL) outcomes for a public health quality assurance system. J Nurs Qual Care. 1993;7:35–45.

Dixon L, Friedman N, Lehman A. Compliance of homeless mentally ill persons with assertive community treatment. Hosp Community Psychiatry, 1993;44:581–583.

Lehman AF. Quality of Life Interview (QOLI). In: Sederer LI, Dickey B, eds. Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Williams and Wilkins; 1996:117–119.

Postrado LT, Lehman AF. Quality of life and clinical predictors of rehospitalization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1161–1165.

Health Resources and Services Administration-Bureau of Primary Heath Care. MUA/MUP. Vol. 2003. Health Resources and Services Administration: 2003. Accessed September 3, 2004. Available at: http://bphc.hrsa.gov/databases/newmua/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Status report on the childhood immunization initiative: national, state, and urban area vaccination coverage levels among children aged 19–35 months—United States, 1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997; 46: 657–664.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Recommendations for preventative pediatric health care. Pediatrics. 2000;105:645–646.

Yu SM, Bellamy HA, Kogan MD, Dunbar JL, Schwalberg RH, Schuster MA. Factors that influence receipt of recommended preventive pediatric health and dental care. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e73.

Hakim RB, Bye BV. Effectiveness of compliance with pediatric preventive care guidelines among Medicaid beneficiaries. Pediatrics. 2001;108:90–99.

Mayer ML, Clark SJ, Konrad TR, Freeman VA, Slifkin RT. The role of state policies and programs in buffering the effects of poverty on children’s immunization receipt. Am J Public Health, 1999;89:164–170.

Cohen JW, Cunningham PJ. Medicaid Physician Fee Levels and Children’s Access to Care. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1995.

Finkelstein JA, Brown RW, Schneider LC et al. Quality of care for preschool children with asthma: the role of social factors and practice setting. Pediatrics. 1995;95:389–394.

Goldman B. Improving access to the underserved through Medicaid managed care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1993;4:290–299.

McLloyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. 1991;61:311–346.

Potts M, Elucidating the relationships between race, socioeconomic status, and health. Am J Public Health, 1994;84:892–893.

Richardson LA, Selby-Harrington ML, Krowchuk HV, Cross AW, Williams D. Comprehensiveness of well child checkups for children receiving Medicaid: a pilot study. J Pediatr Health Care. 1994;8:212–220.

Hahn BA. Children’s health: racial and ethnic differences in the use of prescription medications. Pediatrics. 1995;95:727–732.

Rounsaville D, Hakim RB. Well child care in the United States: racial differences in compliance with guidelines. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1436–1443.

Green NL. Development of the Perceptions of Racism Scale. Image. 1995;27:141–147.

Krieger N, Rowley DL, Herman AA, Avery B, Phillips MT. Racism, sexism, and social class: implications for studies of health, disease and well-being. Am J Prev Med., 1993; 9:83–122.

Alessandrini EA, Shaw KN, Bilker WB, Schwartz DF, Bell LM. Effects of Medicaid managed care on quality: childhood immunizations. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1335–1342.

Campbell PA, Pai RK, Derksen DJ, Skipper B. Emergency department use by family practice patients in an academic health center. Family Med. 1998;30:272–275.

Weinerman ER, Ratner RS, Robbins A, Lavenhar MA. Yale studies in ambulatory medical care. Am J Public Health. 1966;56:1037–1056.

Haddy RI, Schmaler ME, Epting RJ. Nonemergency emergency room use in patient with and without primary care physicians. J Fam Pract. 1987;24:389–392.

Kini NM, Strait RT. Nonurgent use of the pediatric emergency department during the day. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1998;14:19–21.

Zlotnick C, Kronstadt D, Klee L. Foster care children and family homelessness. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1368–1370.

Mainous AG III, Hueston WJ, Love MM, Grifith CH III. Access to care for the uninsured: is access to a physician enough? Am J Public Health. 1999;89:910–912.

Minkovitz C, Holt E, Hughart N et al., The effect of parental monetary sanctions on the vaccination status of young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1242–1247.

Ross DC, Cox L. Preserving Recent Progress on Health Coverage for Children and Families: New Tensions Emerge. Washington, DC. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zlotnick, C., Soman, L.A. The impact of insurance lapse among low-income children. J Urban Health 81, 568–583 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jth141

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jth141