Abstract

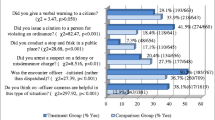

Surveillance cameras are widely used in correctional settings, but there has been little research on their effectiveness, especially in jail settings. Employing a mixed methods approach, this article examines how implementing closed-circuit television in jail housing units in a large Eastern city influences inmate perceptions of safety and incidents of violence and misconduct. Data collected through surveys with 101 inmates and 68 months (56 months from before and 12 from after camera implementation) of administrative records of inmate infractions, incidents of self-harm and officer use of force were analyzed through χ 2 tests, independent sample t-tests, and structural break (time series) analyses. Semi-structured interviews with 14 correctional staff were analyzed qualitatively to provide contextual information. Findings indicate that while inmate perceptions of safety changed after implementing cameras, analyses of reported incidents did not yield any effect. These mixed results may be because of a combination of deterrence and detection effects or to cameras not being paired with more effective monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), passed in 2003, was designed to improve practices associated with the prevention of sexual assault in correctional settings. This included the provision of funds for research on this topic (see the National PREA Resource Center http://www.prearesourcecenter.org/about/prison-rape-elimination-act-prea).

Please see full report, La Vigne et al (2011b), for details on cost-effectiveness analysis.

The procurement process was much lengthier than anticipated, causing significant delays in the implementation. Owing to these lengthy delays, the inmate surveys were administered far in advance of actual implementation.

Exceptions to randomized selection occurred in two units during the pre-intervention surveys. Inmates were only selected from half of all possible inmates in two units, because only half of the list was screened for eligibility by the jail. This resulted in inmates only being selected from the lower tier of cells within these particular units. Furthermore, there were entire units that were unavailable for surveying because of being locked down for violent incidents. These restrictions prevented the researchers from surveying from all eligible housing units. There were additional challenges with passive refusals where substantial numbers of selected inmates refused to come to the gym to hear about the study (where all inmates were offered the option to refuse participation). Therefore, the sample may be vulnerable self-selection bias.

For example, one question might ask about the likelihood of an attack occurring (Very Likely to Very Unlikely), while another question might ask about the number of inmates who are in gangs (Most Inmates to None). Although the response options differ across the different types of questions, all 4-point Likert scale items were coded in the same way: (−3), (−1), (1), (3).

Self-harm events include both self-harm and suicide, as well as hunger strikes and injuries from suspected self-harm. Contraband was only coded if officers were able to seize it (that is, an incident would not be coded as contraband if an assault occurred with a weapon, but the weapon was not recovered). Insubordinate or threatening inmates includes inmate threats toward others (not threats of self-harm), miscellaneous discipline or insubordination and intentional flooding. Includes inmate threats (physical or sexual, but not self-harm), miscellaneous discipline or insubordination and intentional flooding.

It is important to note structural break analyses require the analyst to define the minimum length of a ‘regime’ or potential period of time related to hypothetical events. This is often set to 15 per cent of the total series length (approximately 11 months in this case). However, because of the rapid and frequent changes occurring in jail environments, a 10 per cent regime length was used instead (approximately 7 months). Changes that occur for a shorter period of time than this would be unlikely to be detected.

Other changes unrelated to the study were occurring in the jail during the study period, including policy changes disallowing suicidal inmates to be left alone, providing automatic mental health referrals for suicidal inmates, locking cell doors during the day, program and population changes to one of the intervention units, among others. The jail administrators were unable to confirm start dates for many of these changes.

The larger number of respondents reporting time served time at another jail may be because the study jail is part of a large complex of jails, one of which is a main intake facility, and inmates may count that as a stay in another jail.

Three drug items were included in 43 per cent of the surveys in an attempt to create multiple versions of the survey instrument to dissuade inmates from trying to view other inmates’ surveys. Because of this, there is a smaller sample size (N=90 across both pre and post samples) and less power for these comparisons.

This question was only asked at the post wave.

There was a high non-response rate for this particular item (N=65 of 101 total post respondents), likely also because of inmates’ unfamiliarity with the camera system.

Incidents were coded by the most serious type of incident occurring for each event. For instance, if there was an event where an inmate attacked another inmate, then attacked a staff member, a knife was recovered, pepper spray was used, and the inmate threatened the nurse who was treating his injuries, this would be coded as an assault on staff. (For coding purposes, assaults on staff were considered more severe than assaults on inmates, as there was an extra security risk involved with staff victimization.)

Actual expenditure costs of implementing the system within this jail were $54 740, although the cumulative cost, including economic and opportunity costs, was $85 000 over the 1-year period (with an expected average monthly cost of $2193 in marginal labor costs moving forward). Please see full technical report for more details about the cost-effectiveness analysis.

References

Allard, T., Wortley, R. and Stewart, A. (2006) The purposes of CCTV in prison. Security Journal 19(1): 58–70.

Allard, T., Wortley, R.K. and Stewart, A.L. (2008) The effect of CCTV on prisoner misbehavior. The Prison Journal 88(3): 404–422.

Cameron, A., Kolodinski, E., May, H. and Williams, N. (2007) Measuring the Effects of Video Surveillance on Crime in Los Angeles. CRB-08-007. Sacramento, CA: California Research Bureau.

Clarke, R.V. (1992/1997) Situational Crime Prevention: Successful Case Studies. Reprint New York: Harrow and Heston.

Clarke, R.V. and Homel, R. (1997) A revised classification of situational crime prevention techniques. In: S.P. Lab (ed.) Crime Prevention at a Crossroads. Cincinnati, OH: Anderson.

Dumond, R.W. (1992) The sexual assault of male inmates in incarcerated settings. International Journal of the Sociology of Law 20(2): 135–157.

Gill, M. (ed.) (2006) CCTV: Is it effective? In: The Handbook of Security. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 438–461.

Gill, M. and Loveday, K. (2003) What do offenders think about CCTV? Crime Prevention and Community Safety: An International Journal 5(3): 17–25.

King, J., Mulligan, D.K. and Raphael, S. (2008) CITRIS Report: The San Francisco Community Safety Camera Program. Berkeley, CA: University of California Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society.

Kunselman, J., Tewksbury, R., Dumond, R.W. and Dumond, D.A. (2002) Nonconsensual sexual behavior. In: C. Henley (ed.) Prison Sex: Practice and Policy. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 27–47.

La Vigne, N.G., Lowry, S.S., Markman, J. and Dwyer, A. (2011a) Evaluating the Use of Public Surveillance Cameras for Crime Control and Prevention. (Technical Report) Washington DC: The Urban Institute.

La Vigne, N.G., Debus-Sherrill, S., Brazzell, D. and Downey, P.M. (2011b) Evaluation of a Situational Crime Prevention Approach in three Jails: The Jail Sexual Assault Prevention Project. (Technical Report) Washington DC: The Urban Institute.

Newburn, T. (2002) Introduction of CCTV into a custody suite: Some reflections on risk, surveillance and policing. In: A. Crawford (ed.) Crime and Insecurity: The Governance of Safety in Europe. Portland, OR: Willan Publishing.

Norris, C., McCahill, M. and Wood, D. (2004) The growth of CCTV: A global perspective on the international diffusion of video surveillance in publicly accessible space. Surveillance and Society 2(2/3): 110–135.

Piehl, A.M., Cooper, S.J., Braga, A.A. and Kennedy, D.M. (2003) Testing for structural breaks in the evaluation of programs. Review of Economics and Statistics 85(3): 550–558.

Ratcliffe, J. (2006) Video Surveillance of Public Places. Washington DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Ratcliffe, J. and Taniguchi, T. (2008) CCTV camera evaluation: The crime reduction effect of public CCTV cameras in the city of Philadelphia. PA Installed during 2006. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University.

Taylor, E. (2010) I spy with my little eye: The use of CCTV in schools and the impact on privacy. The Sociological Review 58(3): 381–405.

Travis, L.G., Latessa, E.J. and Oldendick, R.W. (1989) The utilization of technology in correctional institutions. Federal Probation 53: 35–40.

US Department of Justice. (1995) Technology Issues in Corrections Agencies: Results of a 1995 Survey. Longmont, CO: National Institute of Corrections.

Welsh, B.C. and Farrington, D.P. (2002) Crime Prevention Effects of Closed Circuit Television: A Systematic Review. Home Office Research Study 252. London: Home Office, Research, Development and Statistics Directorate.

Welsh, B.C. and Farrington, D.P. (2004) Surveillance for crime prevention in public space: Results and policy choices in Britain and America. Criminology and Public Policy 3(3): 497–526.

Welsh, B.C. and Farrington, D.P. (2008) Effects of closed circuit television surveillance on crime. Campbell Systematic Reviews 17: 2–73.

Wortley, R. (2002) Situational Prison Control: Crime Prevention in Correctional Institutions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

The Jail Sexual Assault Prevention Project was sponsored by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), US Department of Justice. The authors wish to thank the thoughtful peer reviewers whose comments helped to improve the study’s dissemination, and the many Urban Institute staff who have shared their expertise, reviewed earlier report versions and otherwise worked on the project team, including Diana Brazzell, Lisa Brooks, Megan Denver, Brian Elderbroom, Robin Halberstadt, Paula Heschmeyer, Shalyn Johnson, KiDeuk Kim, Akiva Liberman, Samantha Lowry, Dwight Pope, Darakshan Raja, Tracey Shollenberger, Bogdan Tereshchenko, Brian Wade, Charlie Zamiskie and Janine Zweig. We are particularly indebted to our expert consultant on this project, Laura Maiello of Ricci Greene Associates, for providing her expertise in jail design and jail management issues and for reviewing earlier report versions. Finally, we would like to thank the project’s supportive grant monitors, Marilyn Moses and Andrew Goldberg, at the National Institute of Justice. The late Andrew Goldberg was extremely dedicated to building knowledge on the topic of sexual assault in correctional facilities; his commitment to his work and to this topic has had a significant and lasting impact on the field.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This project was supported by Grant No. 2006-RP-BX-0040, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Justice.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Debus-Sherrill, S., La Vigne, N. & Downey, P. CCTV in jail housing: An evaluation of technology-enhanced supervision. Secur J 30, 367–384 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.31

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.31