Abstract

Global investment in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is falling short of the target to close the $2.5 trillion annual financing gap for developing countries. The COVID-19 shock has exacerbated existing constraints for the SDGs and may undo the progress made in he last 6 years in SDG investment. This poses a risk to delivering on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This paper assesses the global trends in both investing in and financing the SDGs, including the myriad of financing instruments launched to respond to the COVID-19 health crisis and its economic and social impacts. It analyses the main challenges for mobilizing funds, channeling investment into SDG sectors, and maximizing positive impact, as well as regulatory dilemmas in promoting SDG investment. The article then elaborates on a set of policy measures for accelerating investment in the SDGs, including four principles for guiding private sector investment, mainstreaming the SDGs into national and international investment policies and promotion strategies, harnessing financial instruments for sustainable development, building special SDGs model zones, and promoting better ESG standards, compliance, and reporting.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The investment requirements for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were first assessed in UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2014. The report identified 10 relevant sectors1 (encompassing all 17 SDGs) and projected an annual investment gap of $2.5 trillion in developing countries.

This projection remains valid today according to a recent review (UNCTAD, 2020). The SDGs have significant resource implications across developed and developing countries and require a step-change in levels of both public and private investment in the SDGs (Zhan, 2014).

Since the adoption of the SDGs in 2015, progress in sustainable development investment has been observed across several SDG sectors, including infrastructure, climate change mitigation, food and agriculture, health, telecommunications, and ecosystems and biodiversity. However, overall growth is falling short of requirements (UNCTAD, 2020a). The COVID-19 shock has exacerbated existing constraints for the SDGs and could undo the progress made in the last six years in SDG investment. International private sector investment flows to developing and transition economies in sectors relevant for the SDGs are expected to fall by about one-third in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic (UNCTAD, 2020e). This poses a risk to delivering on the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. The challenges demand targeted fundraising and investment promotion efforts, in tandem with a wide-ranging multilateral response from all stakeholders to mobilize and channel the resources towards the SDGs (United Nations 2020a, b).

In this context, this paper aims to analyze the key trends of investment in SDGs, including the array of financing instruments launched to respond to the COVID-19 shock. Despite stagnant investment in the SDG sectors, we show that the global effort to fight the pandemic is boosting the growth of sustainability funds, particularly social bonds. Over the next 10 years, the “decade of delivery” for the SDGs, capital markets are expected to significantly expand the offering of sustainability-themed instruments.

In addition to addressing investment and financing trends for the SDGs, the paper discusses challenges for mobilizing funds, channeling investment into SDG sectors, and maximizing positive impact, as well as the major regulatory dilemmas in promoting SDG investment. It then elaborates on a set of key policy measures for accelerating investment in the SDGs, including four principles for guiding private sector investment, mainstreaming the SDGs into national and international investment policies and promotion strategies, harnessing financial instruments for sustainable development, building special SDGs model zones, and promoting better Environmental, Social Governance (ESG) standards, including compliance and reporting.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section two discusses trends and key issues related to the role of the private sector’s investment in the SDGs, and SDG financing trends in global capital markets including in the COVID-19 context. The third section presents key opportunities and challenges, as well as policy options for harnessing sustainable development finance instruments. The fourth section concludes and outlines avenues for future policy-relevant research on international business and development.

INVESTING IN SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

Overall Trends in SDG Investment and Sustainable Finance2

Private investment is crucial for achieving the SDGs, especially given the persistent investment gap observed in developing countries, which is now exacerbated due to the COVID-19 pandemic.3 The public sector remains the dominant funding and financing source of social investment. Yet, there is potential for additional private capital flows into SDG sectors, provided there is greater clarity on invested assets and project incentives. In the current global context, impact and SDG investing open a new door for asset owners and investors. What follows reviews the key investment trends in developing countries across SDG-relevant sectors, and the emerging financing trends for the goals in global capital markets.

SDG investment trends in developing countries

UNCTAD first assessed the investment requirements for the SDGs in UNCTAD (2014) and estimated an annual investment gap in developing countries of $2.5 trillion across the ten relevant sectors. The increase of investment in the SDGs in developing countries – from all sources (domestic and international, public, and private) – is now evident across six out of the ten SDG sectors (Table 1), including infrastructure (which contributes to achieving SDGs 9 and 11), telecommunications (SDG 9), food and agriculture (SDG 2), climate change mitigation (SDG 13), ecosystems and biodiversity (SDGs 14 and 15) and health (SDG 3). However, the order of magnitude is not yet in the range that would make a significant impact in estimated investment gaps - even in sectors where investment growth is observed. In addition, investment in some essential sectors, including education and water and sanitation, is stagnant at best.

International private investment in SDG sectors has not reached the required levels in developing countries. FDI, and in particular greenfield investment and project finance, have been lackluster in relevant sectors, partly because of stagnant global outward investment trends and partly because of regulatory and absorptive capacity constraints in many host countries. In general, the trends in FDI inflows in developing economies based on balance-of-payments data largely mirrors the assessment from the greenfield project data.

Capital spending announcements for greenfield FDI projects (in eight SDG sectors for which data is available) amounted to $134 billion annually on average during 2015–2019 – an increase of 18% from 2010–2014 (Fig. 1). However, this outcome was largely due to heightened investment levels in the first 2 years of the SDG framework (2015 and 2016). In the last 3 years, greenfield investment fell back to pre-SDG levels (UNCTAD, 2020a). The negative trend will produce an adverse impact on SDG investment needed for supporting the recovery in the context of the pandemic. Despite fluctuations across all greenfield investment projects, the number of renewable energy projects almost doubled over the period, contributing to the achievement of SDG 13 on climate action.

International project finance in developing countries announced in 2015–2019 amounted to an annual average of $418 billion, down 32 per cent from the pre-SDG period (2010–2014). Project finance deals comprise mostly power, transport infrastructure, telecommunication, and water and sanitation sectors (Table 2). The number of projects increased by more than 40 per cent, because of many relatively low-cost renewable energy projects. The value of financed projects targeting LDCs remained negligible (about $8 billion, or 6 per cent of the total in all developing economies), and failed to grow over the last five-year period.

Impact of COVID-19 on International Investment in SDGs: Preliminary Assessment

The COVID-19 crisis will make the task of channeling private investment to SDG-relevant sectors in developing countries even more daunting, and in fact, risks undoing the progress made in the last 6 years. UNCTAD (2020d, e) shows that private sector investment trends, which were already fluctuating as described above, are under additional strain. As a result of the pandemic shock, in the first three quarters of 2020, the value of newly announced greenfield investments contracted by 40% and that of international project finance (used for large infrastructure projects requiring multiple investors) by 15%. Investment activity fell sharply across all SDG sectors. In infrastructure and infrastructure industries (including utilities and telecom), international project finance announcements were 62% lower in value. Greenfield project values across food and agriculture, water and sanitation, and health and education were all one- to two-thirds lower than in 2019 (Table 3).

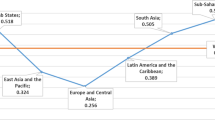

UNCTAD (2020e) further shows that the decline in SDG-relevant investment was much larger in developing and transition economies than in developed countries. In developed economies, gains in investment in renewable energy and digital infrastructure are a first sign of the asymmetric effect that public support packages in developed countries will have on global SDG investment trends. Among developing and transition economies, the impact of the pandemic is more pronounced in the poorer regions. SDG-relevant investment fell by 51% in Africa, 44% in Latin America and the Caribbean, 33% in Asia, and 27% in transition economies (UNCTAD, 2020e).

SDG Financing Trends in Global Capital Markets

Capital markets that are aligned with sustainable development can be instrumental in filling the financing gap for the SDGs. The past decade has witnessed a surge of sustainability-dedicated financial products in a number and types of assets. Sustainability funds mainly target ESG- or SDG-related themes or sectors, such as clean energy, clean technology, sustainable agriculture, and food security. UNCTAD (2020) estimates that funds dedicated to investment in sustainable development have reached $1.2–$1.3 trillion today, including sustainability-themed funds, green bonds, and social bonds. Sustainability dedicated investment consists mostly of green bonds (nearly $260 billion), sustainability-themed equity funds (about $900 billion) and social bonds ($50 billion), plus COVID-19-response bonds ($55 billion) (see Fig. 2).4 Given that almost 90% of funds and bonds are concentrated in developed countries, sustainability financing largely bypasses developing countries, in particular the least developed countries (LDCs).

The current global efforts to fight the pandemic are boosting the growth of sustainability financing, particularly in social bonds (Fig. 2). This is being driven by COVID-19-related bonds, which have been rapidly deployed to fund crisis relief and recovery. Stock exchanges are facilitating the fast-growing market in COVID-19-response bonds and assisting listed companies, especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs), by providing fee relief and introducing flexibility in rules.

Sustainability-themed funds include mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that use ESG criteria as part of their security selection process or seek a measurable positive impact alongside financial returns. Currently, according to UNCTAD’s estimates, there are close to 3100 such funds worldwide, with assets under management of about $900 billion, mostly in developed economies. However, while sustainability-themed funds are valued at about three times various types of ESG bonds in Fig. 2. This does not make them more important for the SDGs. Bonds are securities created in the primary market, in this case for specific sustainability purposes. ESG funds contribute indirectly to the SDGs: as part of the secondary market in which existing securities are traded, they increase demand for shares of companies that pass various ESG/sustainability criteria.

From 2010 to 2019, the number of sustainability-themed funds in Europe and the United States, the two largest markets for sustainable investment, rose from 1304 to 2708, with assets under management growing from $195 billion to $813 billion. Such funds in developing economies remain a relatively new phenomenon. In China, there are 95 sustainability-themed funds, with assets under management of nearly $7 billion as of 2019. Most were created in the last 5 years. ESG funds have also experienced growing traction in Brazil, Singapore, and South Africa in recent years, albeit from a low starting level.

SDG-dedicated bonds are instruments targeted to address several SDGs, with the overall aim to contribute to poverty reduction and equality (see Table 4). Although green and social bonds (COVID-related and other categories) are commonly directed towards the enviroment and climate change—including affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all (SDG 7), they also target industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), and promoting investment in climate action (SDG 13). More recently, they are being oriented towards post-pandemic recovery, including sustainability bonds issued in accordance with the global sustainability bond principles and framework.

Green bonds are one of the foremost innovations in sustainable finance, promoting investment in climate action (SDG 13), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), and sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11). The global green bond market grew rapidly in 2019, to nearly $260 billion - an annual 51% increase. They are primarily used in three sectors (energy, building, and transport), which experienced significant growth annually from 2014 (Fig. 3). However, the green bonds market’s size varies by region (Fig. 4). While the market for green bonds is growing rapidly in Europe and Asia Pacific, and maturing in North America, it is in its infancy in Latin America and the Caribbean, and Africa.5

Social bonds have expanded significantly this year, as a result of the global efforts to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first quarter of 2020, social bonds related to COVID-19 crisis relief raised $55 billion, exceeding the total value of social bonds issued in 2019. Stock exchanges actively support the fast-growing COVID-19-response bond market, for example by waiving listing fees. Financing instruments to assist with the recovery from COVID-19 have been issued by a range of investors, including the private sector and sovereign, supranational, and agency actors (SSAs). Two different types of COVID-themed bonds have been issued:

-

General-purpose bonds (or ordinary operation bonds), as part of a broader COVID-19 response plan by the issuer; and

-

Use-of-proceeds bonds, which can be issued under a framework that is aligned with the International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) Green, Social and Sustainability bonds principles and guidelines (GSSBP) – or a specific COVID-19-response framework (see Table 4).

Use-of-proceeds bonds are relevant for both the post-pandemic recovery and for alleviating the immediate human costs. These types of bonds have largely been issued by SSAs, including central banks and treasuries, as well as social and impact investors. For instance, the Inter-American Development Bank’s sustainable development bond launched a $4.25 billion 3-years sustainable development bond (SDB) – its largest-ever public bond issuance. Proceeds were used to tackle the unemployment effects. Other interventions include the African Development Bank’s $3 billion “Fight COVID-19” Social Bond; and the World Bank’s record $8 billion from global investors in support of its member states.6

In Europe, COVID-19-response bonds have been proposed in various formats to help countries keep borrowing costs low during the crisis, including reframing green bonds to ensure that the post-pandemic economic reconstruction supports the carbon neutrality targets of the EU’s Green Deal. In Asia, Kookmin Bank issued the first Korean COVID-19-response bond (a $500 million social bond) in April 2020. Companies in China have issued more than $2 billion in virus-control bonds, with a third of the funds going towards mitigating the effects of the pandemic.

Over the next 10 years, the “decade of delivery” for the SDGs, capital markets can be expected to significantly expand their offering of sustainability-themed products. Going forward, the challenge will be how to combine growth with a greater focus on channeling funds to SDG-relevant investments in developing countries, especially LDCs, and generate sustainable development impact. To date, most of the assets of sustainability-themed funds are invested in developed countries.

ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL AND GOVERNANCE (ESG) INTEGRATION

The Role of Stock Exchanges and Regulators

In addition to SDG investment and financing, integrating good environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices in business operations to ensure positive investment impact plays a critical role in achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Global capital markets are instrumental in this process. More than half of exchanges worldwide now provide guidance to listed companies on sustainability reporting. Security regulators and policymakers, as well as international organizations, such as the UN Sustainable Stock Exchanges initiative and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), have contributed to expanding ESG integration in business practices.

Stock exchanges provide a platform for sustainable finance and guidance for corporate governance. With the adoption of the UN 2030 agenda, capital markets have an internationally agreed framework for contributing to the creation of sustainable markets and a sustainable society. Increasingly, companies and institutional investors acknowledge the need to align investment and business decisions with positive development outcomes. The SDGs are thus increasingly becoming a focus of investor interest and company reporting for impact, including on gender equality. ESG reporting is now a mainstream expectation of markets, and a rapid transition has been observed in the last 10 years (see Fig. 5). A major challenge, however, is the quality of disclosure and harmonization of reporting standards.

According to the United Nations Sustainable Stock Exchanges (SSE) initiative, which reports the sustainability activities and mechanisms of 102 stock exchanges around the world, the last decade has witnessed a substantial increase across a range of sustainability mechanisms undertaken by exchanges (UNSSE, 2019). Such mechanisms and activities encompass sustainability reporting, training, and regulations as well as the development of relevant tools and platforms for the development and transaction of sustainability-themed financial products (Fig. 6).

Training on ESG remains the most relevant activity, with over half of the stock exchanges offering at least one training course or workshop. Exchanges also promote ESG disclosure (SDG 12.6), where half of the SSE members (48) currently publishes guidance on disclosing ESG information. The number of stock exchanges with sustainability bond segments, primarily green bonds (SDG 13), expanded significantly since the launch of the SDGs to a total of 31 in 2019. Importantly, the number of exchanges covered by mandatory rules on ESG disclosure (SDG 12.6), currently 24, has more than doubled in the past 5 years.

In addition to sustainability standards, one SDG on which companies are increasingly expected to report is gender equality. About 70% of the world’s 5000 largest MNEs now report on progress in this area (UNCTAD, 2020b). Overall, women’s representation remains unequal. Regulation and investor pressure have led to better representation at the board level, but not at managerial levels. The implementation of gender-equality policies related to flexible work and childcare remains weak.7 UNCTAD’s analysis shows that globally about 80% of companies have published a diversity policy.8

SDG Integration and Sustainability Reporting

The SDGs have become the universally accepted benchmark for sustainability impact and are increasingly integrated into corporate sustainability policies and reporting. While environmental and social governance reporting has hitherto been a voluntary and a supplementary activity to core business practices, the realization of the SDGs will depend on a transition towards full ESG compliance (Kolk et al., 1999, 2020). ESG initiatives in the private and public sectors have been aligned with the SDGs, by mapping and integrating the goals across organizations and industries. Mapping the SDGs to the work of an organization is one of the most common ways in which the SDGs have been integrated into sustainable corporate behavior. The initiatives have been integrated into company and organizational road maps, missions, pathways, and codes of conduct. For instance, the Ethical Trading Initiative, Transparency International, and the International World Cocoa Foundation, have used all or selected SDGs to frame their visions and missions (UNCTAD, 2020).

Progress in reporting by MNEs will aid in boosting the private sector’s contribution to the SDGs. The Global Reporting Initiative, which produces the world’s most widely adopted sustainability reporting standard, charted the SDGs to its reporting standard in the SDG Compass, and provides an inventory that maps business indicators to SDG targets. It has also published three SDG reporting tools to help companies incorporate SDG reporting into their practices, as well as recommendations for national policymakers on using corporate reporting to strengthen the SDGs.9

ACCELERATING INVESTMENT IN THE SDGS: KEY CHALLENGES AND POLICY RESPONSES

International business research has contributed to the understanding of the private sector’s role in the SDGs framework, also helping to better inform policy-making.10 Evidence-based policy-making, that is, policy decisions effectively informed by scientific research, is fundamental for assessing the impact of businesses activities on sustainable development. However, the SDG framework is defined by complex and interrelated issues, including the involvement of multiple actors at multiple levels across numerous countries (van Tulder 2018, van Tulder and Keen, 2018, Eden and Wagstaff, 2020). On this basis, academic research can provide policymakers frameworks to assess the growing challenges to meet the SDGs, and possibly provide solutions to those challenges.

Linkages between Policy and Practice

Despite the policy relevance and the increase in SDG reporting initiatives among private agents, research on the role of the private sector in achieving international policy goals, including the SDGs, is still limited. For example, van Zanten and van Tulder (2018) outline a plan and put forward policy recommendations for a more proactive engagement of MNEs in sustainable development. Based on a survey from European and North American Financial Times Global 500 companies, the study indicates that MNEs engage more with SDG targets and goals that are actionable within their own value chain operations. Differences in SDG engagement based on MNEs’ home- and host-country standards were also found to be significant determinants of engagement. However, not all actors are equably prepared to contribute to all aspects and perform across all areas of the SDG agenda. Therefore, there is the need for a comprehensive and forward-looking policy framework comprising an investment-chain approach from upstream to downstream.

In designing investment policy frameworks, it is crucial to consider the complementarity and limited substitutability between public and private resources for development (Schmidt-Traub and Sachs 2015). Public investment is a driver of economic growth, where policies that promote public investment can deliver high returns in terms of economic development. At the same time, the benefits of private investment and ample opportunities from the private sector are well recognized. The private sector has evident advantages to deliver on the SDGs beyond investment, including innovation, responsiveness, efficiency, and provision of specific skills and resources. Private investment, and private sector-led initiatives, such as research and development partnerships, knowledge-sharing platforms, technology and skills transfer, and infrastructure investment have the potential to kick-start development, can lead to productivity gains, generate better quality jobs, strengthen skills and promote technological advances, and thus achieve sustainable development (Zhan and Karl, 2016). Moreover, by promoting sustainable development through incentive programs, governments could improve the viability of vital investments (such as in electricity, water supply, health and education services), making those services more accessible and affordable for the poor, and the jurisdiction a more attractive investment destination.

Despite the expectations on the private sector to deliver more sustainable and responsible practices, there are several barriers and challenges. The challenges are often magnified by the tension between the dominant business model, which is based on short-term planning with a narrow focus on finances, and a tangential agenda of longer-term planning with economic, social, and environmental goals (Scheyvens et al., 2016). Zhan and Karl (2016) argue that incentives are a key policy tool for promoting investment in sustainable development. The study advocates for the redesign of investment incentive schemes, reorienting them from a location-based to a sustainable-development based system to attract investment in SDG-relevant sectors and to achieve sustainable development outcomes. Investment incentives are, however, only one element of a sustainable development-oriented policy strategy and guiding framework. Such a policy needs to address the foremost constraints that investment in SDG-related sectors and industries may encounter.

To address these challenges, governments would need to employ a wide range of policy options. Moreover, the scale of the investment needs would mandate an internationally collaborative effort that prompts synergies amongst all stakeholders, especially between developed and developing countries. Following its pioneering research on estimating SDG investment needs, UNCTAD has been carrying out research on developing a holistic policy package to help governments meet SDG investment needs11.

Policy Challenges and Dilemmas

Policy actions for promoting private investment in SDGs need to address three main challenges. Firstly, challenges to mobilizing funds in financial markets include market failures and a lack of a sound system for corporate disclosure of environmental, social, and governance performance, misaligned incentives for market participants, and start-up and scaling problems for innovative financing solutions. Secondly, hurdles to channeling funds into SDG sectors include entry barriers, inadequate risk-return ratios for SDG investments, a lack of information and effective packaging and promotion of pipeline bankable projects, and a lack of investor expertise. Thirdly, challenges in maximizing the positive impact and minimizing the risks and drawbacks of private investment in SDG sectors including persistent weak absorptive capacity in some developing countries, social and environmental impact risks, and the need for stakeholder engagement and effective impact monitoring.

Increasing the involvement of private investors in SDG-related sectors, many of which are sensitive or of a public service nature, leads to three policy dilemmas, which entail regulatory and public policy concerns. The first dilemma relates to the risks involved in increased private sector participation in sensitive sectors. Private sector provisions in social sectors such as health care and education in developing countries, for instance, can have negative effects on standards unless strong governance and oversight is in place, which in turn requires capable institutions and technical competencies. Private sector involvement in essential infrastructure industries, such as power or telecommunications, can be sensitive in developing countries where this implies the transfer of public sector assets to the private sector. Moreover, business operations in infrastructure such as water and sanitation are of particular concern due to the basic-needs nature of these sectors.

The second dilemma stems from the need to maintain quality services, affordable and accessible to all. The fundamental hurdle for increased private sector contributions to investment in SDG sectors is the inadequate risk-return profile of many such investments. Many mechanisms exist to improve the risk-return profile for private sector investors. Increasing returns, however, must not lead to the services provided by private investors ultimately becoming inaccessible or unaffordable for the poorest in society. Allowing energy or water suppliers to cover only economically attractive urban areas while ignoring rural needs, or to raise prices of essential services, is not a sustainable outcome.

A third dilemma results from the respective roles of public and private investment. Public and private investment are critical for achieving the prospective SDGs - the latter is expected to complement, not replace, the former. Governments – through policy and rulemaking – need to be ultimately accountable with respect to provision of vital public services and overall sustainable development strategy. Given the complex and multifaceted challenges faced by investors and countries, which are heightened due to COVID-19, achieving the SDGs will require comprehensive investment policies. In this context, governments need to strike a balance between public and private investments.

Policy Framework for Sustainable Development

UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development (IPFSD), a holistic strategic framework and an action Plan, aims at providing guidance, mobilizing and channeling funds into SDG sectors, and maximizing their impact (Zhan, 2016). The IPFSD remains a valid point of departure to address private sector investment and enhancing policies to support SDG impact, and to address the challenges and dilemmas discussed in the previous section. The framework provides concrete recommendations for the advancement of investment for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda in the different areas outlined, including the highly uncertain investment outlook, which depends on the duration of the health crisis, and on the effectiveness of policy interventions to mitigate the economic effects of the pandemic.

The framework suggests four guiding principles for private sector investment in the SDGs.

First, balancing liberalization with regulation. SDG sectors often, given their nature, provide public goods and frontline services; private sector involvement requires careful balancing of market access considerations with appropriate public regulations and possible oversights.

Second, balancing the need for attractive risk-return rates with the need for accessible and affordable services for all. The risks undertaken by corporate actors and their expected returns need to be weighed against the requirement to ensure the accessibility and affordability of goods and services.

Third, balancing a push for private investment with public investment. Private sector involvement is not a panacea for solving the SDG financing problem but can play an important role in complementing and supporting public sector engagement. Mobilizing private and public funding must follow a coherent strategy.

Fourth, balancing the global scope of the SDGs with the need to make a special effort in least developed countries (LDCs) and other vulnerable economies.12 The persistent development challenges in such countries requires national and international measures tailored to their specific contexts.

UNCTAD’s policy framework and related action plan provide a range of policy options to respond to the investment mobilization, channeling and impact challenges, faced especially by developing countries. The key policy options, which should be followed simultaneously with changing the global business mindset, are discussed below.

Mainstreaming the SDGs in investment policies

Today, more than 150 countries have adopted national strategies on sustainable development or revised existing development plans to reflect the SDGs. For instance, national sustainable development strategies – which comprise the broad set of national sectoral economic and social strategies – often highlight the need for additional financial resources and a lack of domestic capacity to meet the SDGs. However, concrete action plans for attracting more investment in the SDGs are vague or non-existent. Research by UNCTAD, based on 128 voluntary national reviews, reveals that although many of these strategies highlight the need for additional financial resources, very few contain concrete roadmaps for the promotion of investment in the SDGs (UNCTAD, 2020a).

Existing investment promotion instruments applicable to the SDGs are limited in number and follow a piecemeal approach. UNCTAD’s global review of national investment policy regimes shows that less than half of UN member states hold specific promotion tools for investment in the SDGs. Each country, on average, targets no more than three SDG-related sectors or activities in its regulatory framework. Many developing countries, however, do not have any such policy instruments in place. Countries promote inward investment in the SDGs primarily through targeted incentive schemes. Several key SDG sectors, such as health, water and sanitation, education and climate change adaptation, are rarely covered by specific investment promotion measures. Developed economies also promote outward investment through state guarantees and loans applying sustainability criteria.

Since the adoption of the SDGs, efforts have been made to enhance promotion of investment in SDG sectors. In total, 55 countries implemented almost 200 policy measures related to these sectors, with most of them aiming at liberalizing or facilitating investment. Most policy changes affected food and agriculture, transportation or innovation and were adopted by developing economies, with developing Asia alone responsible for 42% of them. The pandemic has triggered a shift in priorities towards more promotion of investment in the health sector, food security, and digitalization. Since September 2015, close to 50 regulatory amendments aimed at tightening existing foreign investment regimes applicable to SDG sectors (e.g., in telecommunication, power, as well as food and agriculture) became effective, most of them relating to foreign investment screening mechanisms.

In addition to national investment policies, factoring in the SDGs in international investment treaties presents a daunting task. The majority of the 3300 existing treaties pre-date the SDGs, a large number of which contain provisions inconsistent with the SDGs. Since the adoption of the SDGs in 2015, 190 new international investment agreements (IIAs) have been concluded. Of those, only 30% contain provisions addressing the SDGs directly.

In light of the above, a more systemic approach is needed to mainstream SDGs into the national investment policy framework and international investment treaty regime. At the national level, a coherent and comprehensive road map for attracting investment into SDG sectors and ensuring it contributes to sustainable development should be an integral part of national strategies and development plans based on the Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development (UNCTAD, 2015). At the international level, the SDGs should be a core objective when negotiating new IIAs and modernizing “old-generation” treaties, based on UNCTAD’s IIA Reform Package (UNCTAD, 2018).

Harnessing sustainable development finance instruments

As indicated in the “Investing in Sustainable Development Goals” section above, a significant growth in sustainable development finance instruments has been observed in recent years. Yet most of these funds circulate within developed economies, especially in the context of climate change mitigation and renewable energy. Over the next decade, capital markets are expected to significantly expand their offering of sustainability-themed products. The challenge will be how to combine growth with a greater focus on channeling funds to SDG-relevant investment projects in developing countries. In this context, there is a need for better policy coordination at the international level to channel sustainable development finance resources to developing economies, particularly to LDCs.

There are two critical bottlenecks that inhibit flows of funds to developing economies. Firstly, barriers to outflows of sustainable investment funds from major home economies. Secondly, there are considerable barriers to inflows in developing economies. Regarding the former, the key issue is that prudential responsibility of funds in developed economies and risk perception with investing in developing countries. To overcome this challenge, sovereign guarantees and support from developed economies can be instrumental in facilitating the outflow of sustainable investment funds to developing economies.13

Moreover, there is often a lack of clarity on investment policy in host economies, concerns about regulations, and a dearth of investable projects. In all of these areas, governments in developing economies need to adopt a holistic and comprehensive policy framework that is conducive to the inflow of sustainable investment resources, offers investors protection, and is transparent. Using performance indicators linked to sustainable finance instruments is one of the tools that could help developing countries to attract sustainable financing.

Policymakers in both developed and developing countries could look to replicate the successful models of green finance found in green bond markets. This includes developing sovereign green bonds as well as encouraging private enterprises to issue green bonds to fund climate adaptation and mitigation efforts. This is particularly critical for regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean, and Africa, where the need to transition to sustainable economic models is the largest, and which face the highest costs due to climate change.

COVID-19 bonds

Recently, COVID-19-themed bonds have played a key role in helping alleviate the immediate human and economic costs of the pandemic, also contributing to the long-term recovery. The instruments to respond to the pandemic have increased the market size, and are likely to increase prevalence of social bonds compared to green bonds in the short term, as well as to enhance the adaptation of different responsible investment practices across a wide array of financial products. Market size may also increase due to COVID-19, as various stakeholders try to leverage additional sources of financing to contend the impact of the pandemic.

As discussed in the “Investing in Sustainable Development Goals” section, an increasing number of countries and supranational institutions are already rolling out such bonds. However, to optimize the benefits from such instruments and ensure that they do not create unsustainable levels of debt in the long run, stakeholders should adopt a tiered, strategic, and evidence-based approach pivoted around transparency, good governance, and robust impact-assessment mechanisms.

Another policy issue is linking the COVID-19 bonds strategic vision with long-term goals following a needs-based assessment. Many countries have immediate needs related to healthcare and social protection due to the pandemic, but it is critical that raising financial resources and spending plans correspond to long-term development objectives. For example, a given country’s additional spending on healthcare should consider addressing immediate needs and structural shortcomings of health systems, especially in developing countries (Zhan and Spennemann 2020).

Similarly, with regard to the loss of employment and increasing poverty rates due to the economic shock of the pandemic, investment should address both immediate social protection needs especially of the most vulnerable population groups and at the same time lay the foundation for structural transformation of economies to enhance employment-generating local production in a way that capitalizes on the changing global production landscape. For instance, UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2020 highlights how GVCs are transforming due to both the pandemic as well as existing megatrends of technology, retrenchment in global governance, and the sustainability imperative.

Transformation will also depend on sustainability concerns, including differences between countries and regions on emission targets, ESG standards, market-driven changes in products and processes, and supply chain resilience measures. Adapting to these shifts in international production patterns presents new challenges for developing countries. The main challenges in the new era of international production involve increased divestment, relocations, investment diversion, and a shrinking pool of efficiency-seeking investment, implying tougher competition for FDI. Changes in the locational determinants of investment will negatively affect developing countries’ ability to attract MNE operations. In contrast, new opportunities are likely to arise due to investors looking to diversify supply bases to enhance production resilience.

The other consideration for policymakers to make COVID bonds successful is to ensure robust and real-time impact measurement using an evidence-based approach. This could allow for higher transparency and good governance mechanisms for COVID bonds, an issue that is critical for both the intended beneficiaries and investors. One instrument that could contribute towards greater transparency and impact is the use of sustainability-linked bonds (SLB) adapted to COVID recovery. SLB bonds are “any type of bond instrument for which the financial and/or structural characteristics can vary depending on whether the issuer achieves predefined Sustainability/ESG objectives” (ICMA, 2020, page 2). COVID-19-linked SLBs can be instrumental in incentivizing the achievement of SDG-related outcomes, such as ensuring access to vaccines, enhancing medical services, and widening the social protection net.

Building SDG model zones

Fostering new forms of partnerships is one of the key policy options for mobilizing investment in the SDGs. Today there are over 5400 special economic zone across 147 economies, and more than 500 new zones are in the pipeline (UNCTAD, 2019b). Booming SEZs result from a new wave of industrial policies and a response to increasing competition for internationally mobile investment. There is significant opportunity and potential for existing zones to transition into SDG model zones, and to build the new generation of zones following a sustainable development blueprint. Such zones would aim to attract investment in SDG-relevant activities, adopt the highest levels of ESG standards and compliance, and promote inclusive growth through linkages and spillovers (Zhan et al, 2020). SDG model zones could act as catalysts to transform the “race to the bottom” for the attraction of investment (through lower taxes, fewer rules, and lower standards) into a race to the top – making sustainable development impact a locational advantage (Zhan, 2017).

The process of modernizing zones and building SDG Model Zones can benefit from a global exchange of experience and good practices. Also, with more zones being developed through international partnerships, a global platform that brings together financing partners, SEZ developers, host countries, investment promotion agencies and outward investment promotion agencies, as well as impact investors, can accelerate the transition towards sustainable development-oriented zones. The objective should be to make SEZs work for the SDGs: from privileged enclaves to sources of widespread benefits. SDG model zones could help to address existing supply-side constraints, particularly in LDCs.

Promoting better ESG standards, compliance, and reporting

Progress on investing in the SDGs is not only related to mobilizing funds and channeling them to priority sectors in developing economies, especially in structurally vulnerable countries. It also entails integrating good environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices in business operations to ensure positive investment impact. As discussed in the second section, there is a close link between SDGs and ESGs reporting standards, relating to business conduct, the economic, social, and governance factors, as well as the overall global socioeconomic and environmental impacts the SDGs entail. Even if the SDGs agenda has shaped the global discourse on corporate sustainability, such initiatives must now reinforce the implementation and measurement of the contributions to the SDGs, which must be supported by comprehensive reporting.

With rapid advancement in stock exchanges’ sustainability practices, policymakers need to provide written guidance on ESG disclosure, and should seek to formalize such guidance in mandatory listing regulations. Countries with ESG listings as a voluntary requirement should also consider shifting to a mandatory regulatory requirement. In this regard, the UN Sustainable Stock Exchange Initiative has been instrumental over the past decade, leading the movement of mainstreaming ESG into the global capital markets, and through the exchanges worldwide into the business practices and disclosure of listing companies from both developed and developing countries (UN SSE, 2019). Institutions such as IOSCO could assist developing countries to establish guidance for security market regulators on consistent mandatory ESG disclosure rules. Given the diverse reporting capacities and standards, particularly among developing countries, innovative initiatives should be pursued, including enhancing the capacities of small and medium enterprises, and promoting sustainability indicators for new actors such as family businesses.

Bringing small and medium enterprises (SMEs) on board for ESG compliance and reporting

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) represent a major share of economic activity in developing countries. Bringing SMEs on board regarding the adherence of ESG compliance and reporting standards can enhance their role in the pursuit of the SDGs. However, SMEs in developing countries often have limited capacity and expertise for reporting on ESG standards and there are often no institutional guidelines or requirements for such reporting. In difficult economic conditions for SMEs due to the pandemic, the making of such reporting mandatory may also increase the costs of operation.

In this context, viable solutions and support for SMEs’ reporting should be explored, including by relaxing mandatory reporting requirements at the firm level. Given existing constraints in developing countries, SME industry associations that compile joint reporting on behalf of all members could be a solution. These industry associations can be set up by governments or the private sector themselves, or as public–private partnerships. Intermediate professional firms that specialize in sustainable development reporting could act as intermediates in both collecting data and information while also helping SMEs enhance capacity for better ESG reporting and compliance. Governments could provide an enabling environment for such associations to function and model the overall regulatory framework to their specific contexts.

SMEs and governments can also benefit from the advisory and capacity-building services of the UN Intergovernmental Working Group of Experts on International Standards of Accounting and Reporting (ISAR) to improve reporting standards. ISAR is the United Nations’ focal point on accounting and corporate governance matters. UNCTAD serves as ISAR’s secretariat, providing substantive and administrative inputs to its activities. ISAR reviews developments in the field of international reporting and promotes best practices for corporate governance. Within the context of Agenda 2030, ISAR contributes to the realization of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through enhanced transparency and sustainability standards for companies.

Sustainable development initiative for family businesses

Family businesses also have a role in advancing the agenda on better reporting and adherence to ESG standards. UNCTAD and The Family Business Network (FBN) jointly established the Global Initiative Family Business for Sustainable Development (FBSD) [fbsd.unctad.org], a novel partnership between the United Nations and the global family business community. The network aims at mobilizing business families and their firms to embed sustainability into their business models and strategies, and commit to concrete, measurable contributions towards the SDGs. Key components of the FBSD Initiative include, among others, the family business sustainability pledge and the adoption of transparent and comparable core sustainability indicators for family firm reporting.14

The Sustainability Indicators for Family Business (SIFB) build on UNCTAD’s Guidance on core indicators (GCI) for entity reporting on contribution towards the implementation of the SDGs. The core indicators were developed through consultations and consensus-building among key experts and endorsed by UNCTAD’s Intergovernmental Working Group of Experts on International Standards of Accounting and Reporting (ISAR). The 33 core indicators outline the base-line reporting companies are required to provide, to enable governments and other stakeholders to evaluate the contribution of the private sector to the implementation of the SDGs.

In addition to the reporting framework of the core indicators, FBN elaborated further disclosure elements to capture and recognize family business’ efforts in contributing to the implementation of SDGs. In total, SIFB covers approximately 40 indicators mapped to ten different SDGs. The reporting framework will be periodically reviewed in view of its applicability for family firm entities. Family businesses can take advantage of this resource and join the growing network of family businesses that have aligned their operations with sustainable development to varying degrees and through different channels.

CONCLUSION

This paper discusses the trends in SDG investment, and the significant investment gaps that threaten progress towards the SDGs. The article assesses the array of financing instruments launched to respond to the COVID-19 health crisis and its economic and social impacts. The COVID-19 pandemic is significantly exacerbating SDG financing gaps in developing economies, and runs the risk of undoing the progress made in SDG investment since the launch of the 2015 global development agenda. This threatens progress on the SDGs across all countries, particularly in the LDCs and other structurally weak economies. International private investment will be key to alleviate public sector resource shortfalls for SDG-relevant investment and to spearhead the global campaign to build back better. With only 10 years left to complete the sustainable development agenda, the recent stagnation in private flows to the developing countries – further affected by the pandemic – poses a daunting mission. Policymakers, investors, and producers face tremendous challenges and regulatory dilemmas in mobilizing and channeling investment for sustainable development.

UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development (UNCTAD, 2015) presents a comprehensive set of investment principles and policy options that place inclusive growth and sustainable development at the center of the endeavor to attract and generate benefits from investment. Some of the policy areas that deserve special attention from policymakers and the business community are highlighted in this paper, including increasing private sector investment, harnessing sustainable finance instruments, leveraging COVID themes finance, and promoting better ESG standards. The paper also underlines practical ways and means to pursue these policy options. Importantly, the paper underscores that any strategy for investment in sustainable development should include a focus on facilitating investment in different economic and social sectors of the SDGs.

There are other issues beyond investment which can affect the path to achieving the SDGs, and which deserve broad-based policy interventions, particularly in low- and middle-income economies. Such challenges include lack of capital, technology, and skills for production; low product quality and standards – particularly in sensitive sectors, inadequate or nonexistent enabling policy frameworks, small markets – with weak purchasing power – unstable demand, and poor infrastructure. The global health crisis is unveiling bottlenecks not only in the health sector but also in productive sectors linked to global trade and production.

Quality and reliable information on SDG-related investment and actions are also crucial for research on investment and inclusive business practices. The accuracy of available information varies, depending on the source and the subsequent ability of the reporting entity to assure this information. It is therefore important that entities use the right mix of internal and external sources to ensure the reliability of published data.

A frontier for policy relevant research is exploring the innovative ways and means to untap the potential of private investment, including capital markets (Zhan, 2020). Despite the boom in sustainability-dedicated investment and pressure on ESG indicators, funds currently circulate mostly among developed economies, and do not reach developing countries at the scale or in the sectors most needed. Another topic for future research, and challenge for policymakers, is how to tap into the vast potential of institutional investment and other sources for financing the SDGs. This includes research on how to mobilize and channel sovereign wealth funds and pension wealth funds, as well as impact investment and global philanthropic funds towards the 2030 development agenda. The issues and frameworks discussed in this paper underline the need for more consistently conceived and carefully crafted investment policies and promotion strategies for sustainable development.

Notes

-

1

The SDG-relevant investment sectors first defined in UNCTAD’s 2014 World Investment Report covered basic infrastructure sectors (roads, rail and ports; power stations; telecommunication; water and sanitation), food security (agriculture and rural development), climate change mitigation and adaptation, health and education (UNCTAD, 2014). The report highlighted the need for private international investment, as a supplement to public and domestic investment, to bridge the financing gap.

-

2

This section is in general based on the findings presented in UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2020 (see UNCTAD, 2020a).

-

3

See also UNCTAD (2019).

-

4

Impact investment also falls into this category. However, because of the large overlap between impact investing and sustainability-themed bonds and funds (green bonds and a significant share of sustainable funds are also categorized as impact investing), the value of impact investing is not added to the value of sustainability-dedicated investment so as to avoid double-counting.

-

5

Proceeds from green bonds in Africa remained below $1 billion in the period 2015-2019 years and are negligible compared to other regions.

-

6

https://www.iadb.org/en/news/idb-launches-its-largest-sustainable-development-bond; https://treasury.worldbank.org/en/about/unit/treasury/ibrd.

-

7

UNCTAD’s report (2020 forthcoming) presents policy recommendations based on academic research on the role of foreign direct investment and multinational enterprises to spread gender equality and female empowerment around the globe. The report provides evidence from all major regions of the world, on the firm-level differences in labor market outcomes for women across foreign and domestic firms.

-

8

The degree to which such policies translate into concrete outcome can be proxied by the presence of flexible working arrangements, or the provision of childcare services that might positively benefit women and facilitate their participation in labor markets. The number of companies with such arrangements or facilities is far lower than those with a diversity policy.

-

9

In 2019, UNCTAD published the Guidance on Core Indicators as a framework for corporate reporting on their contribution towards the attainment of the SDGs.

-

10

For example, Scheyvens et al. (2016).

-

11

UNCTAD (2020) presents UNCTAD’s transformative actions and related plan for a “Big Push” in private sector investment in the SDGs. This paper presents the main actions and four immediate priorities focusing on the pandemic environment.

-

12

Least developed countries (LDCs) are low-income countries confronting severe structural impediments to sustainable development. They are highly vulnerable to economic and environmental shocks and have low levels of human assets. There are currently 47 countries on the list of LDCs which is reviewed every 3 years by the Committee for Development (CDP) of the United Nations.

-

13

For example, the US established in 2019 the International Development Finance Corporation, which has a global investment capitalization of $60 billion. It will provide support to projects in the form of equity, debt financing, risk insurance, and technical development in developing regions around the world.

-

14

Some papers have shown a positive relationship between family ownership and a higher inclination to doing good – which could be directly linked to the SDG equality focus (e.g., Crilly et al., 2016).

REFERENCES

Crilly, D., Ni, N., & Jiang, Y. 2016. Do-no-harm versus do-good social responsibility: Attributional thinking and the liability of foreignness in the MNC. Strategic Management Journal, 37(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2388.

Eden, L., & Wagstaff, M.F. 2020. Evidence-based policymaking and the wicked problem of SDG 5 Gender Equality. Journal of International Business Policy. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00054-w.

International Capital Market Association, ICMA. 2020. Green, Social and Sustainability Bonds: A High-Level Mapping to the Sustainable Development Goals, June.

Kolk, A., van Tulder, R., & Welters, C. 1999. International codes of conduct and corporate social responsibility: Can transnational corporations regulate themselves? Transnational Corporations, 8(1): 143–180.

Kolk, A., Kourula, A., Pisani, N., & Westermann-Behaylo, M. 2020. The state of international business, corporate social responsibility and development: Key insights and an application to practice. In P. Lund-Thomsen, M. W. Hansen & A. Lindgreen (Eds.), Business and development studies: 257–285. London: Routledge.

Scheyvens, R., Banks, G., & Hughes, E. 2016. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sustainable Development, 24(6): 371–382

Schmidt-Traub, G., & Sachs, J. D. 2015. Financing sustainable development: implementing the SDGs through effective investment strategies and partnerships. Working Paper, Sustainable Development Solution Network.

Van Tulder, R. 2018. Business and the Sustainable Development Goals: A framework for effective corporate involvement. Rotterdam: Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University.

van Zanten, J. A., & van Tulder, R. 2018. Multinational enterprises and the Sustainable Development Goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. Journal of International Business Policy, 1(3): 208-233

van Tulder, R., & Keen, N. 2018. Capturing collaborative challenges: Designing complexity-sensitive theories of change for cross-sector partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 150: 315–332.

UN Global Compact. 2017. Making global goals local business—A new era for 42 responsible business. New York: United Nations Global Compact.

UNCTAD. 2014. World Investment Report 2014 Investing in the SDGs: An Action Plan. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD. 2015. Investment policy framework for sustainable development. New York and Geneva: United Nations

UNCTAD. 2018. UNCTAD’s reform package for the international investment regime. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD. 2019. SDG investment trends monitor. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

UNCTAD. 2019. World Investment Report 2019: Special economic zones. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD. 2020a. World Investment Report 2020: International production beyond the pandemic. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD. 2020b. The international transmission of gender policies and practices: The role of multinational enterprises, forthcoming.

UNCTAD. 2020c. The changing IIA landscape: New treaties and recent policy developments. International Investment Agreements Issue Note, Issue 1 (July), Geneva

UNCTAD. 2020d. Global Investment Trends Monitor, No. 36, Geneva.

UNCTAD. 2020e. SDG Investment Trends Monitor. UNCTAD: Geneva.

United Nations. 2020a. The Sustainable Development Report 2020: The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19.

United Nations. 2020b. Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2020, New York.

UNSSE. 2019. 10 years of impact and progress: Sustainable stock exchange 2009-2019. Geneva: UNCTAD. https://sseinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/SSE-10-year-impact-report.pdf

Zhan, J. X. 2014. Investment in Sustainable Development Goals. In Capital Finance International, Oct. 2014 (www.cfi.co).

Zhan, J. X. 2016. A new generation of investment policies. In The Sustainable Development Goals as business opportunities. Paris: OECD.

Zhan, J. X. 2017. SEZs: Five routes to enhance sustainability. World Finance, Winter issue.

Zhan, J. X., & Karl, J. 2016. Investment incentives for sustainable development. In A. T. Tavares-Lehmann, P. Toledano, L. Johnson, & L. Sachs (Eds.), Rethinking investment incentives: Trends and policy options. https://doi.org/10.7312/columbia/9780231172981.003.0009.

Zhan, J. X., Casella, B., & Bolwijn, R. 2020. Towards a new generation of special economic zones: Sustainable and competitive. In A. Oqubay & J. Lin (Eds.), Oxford handbook on industrial hubs and economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zhan, J. X., & Spennemann, C. 2020. Ten actions for building productive capacity in LDCs for medicine. Health Policy Watch, May 25. https://healthpolicy-watch.org/ten-actions-to-boost-lmics-productive-capacity-for-medicines/.

Zhan, J. X. 2020. WIR@30: Paradigm shift and a new research agenda for the 2020s. AIB Insights, 20(4): https://doi.org/10.46697/001c.18045.

Acknowledgements

The section on trends in this paper draws on the World Investment Report 2020 and some ongoing research, where the authors have been taking the lead. The paper provides further analytical angles on key investment issues in the context of the SDGs, the impact of COVID-19, and investment policies. The authors are grateful to Hafiz Mirza, Rob van Tulder, and to anonymous referees for useful comments and suggestions. We also thank Arslan Chowdary and Kumi Endo for valuable research assistance. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ and do not represent the views of the United Nations or its member states.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Hafiz Mirza, Area Editor, and Kathleen Sexsmith, Guest Editor, 19 December 2020. This article has been with the authors for one revision and was single-blind reviewed.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, J.X., Santos-Paulino, A.U. Investing in the Sustainable Development Goals: Mobilization, channeling, and impact. J Int Bus Policy 4, 166–183 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00093-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00093-3