Abstract

Market liberalization in emerging-market economies and the entry of multinational firms spur significant changes to the industry/institutional environment faced by domestic firms. Prior studies have described how such changes tend to be disruptive to the relatively backward domestic firms, and negatively affect their performance and survival prospects. In this paper, we study how domestic supplier firms may adapt and continue to perform, as market liberalization progresses, through catch-up strategies aimed at integrating with the industry's global value chain. Drawing on internalization theory and the literatures on upgrading and catch-up processes, learning and relational networks, we hypothesize that, for continued performance, domestic supplier firms need to adapt their strategies from catching up initially through technology licensing/collaborations and joint ventures with multinational enterprises (MNEs) to also developing strong customer relationships with downstream firms (especially MNEs). Further, we propose that successful catch-up through these two strategies lays the foundation for a strategy of knowledge creation during the integration of domestic industry with the global value chain. Our analysis of data from the auto components industry in India during the period 1992–2002, that is, the decade since liberalization began in 1991, offers support for our hypotheses.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

With the onset of market liberalization or privatization, domestic firms in emerging and transition economies confront environmental change that is systemic and “avalanche-like” (Suarez & Oliva, 2005). Such changes are qualitatively different from industry-specific changes (such as deregulation) faced by firms in advanced market economies (Newman, 2000; Peng, 2003). For instance, there is an economy-wide reshaping of institutional environments, and the increased entry and participation of multinational enterprises (MNEs) (McDermott & Corredoira, 2010).

In a highly regulated economy, firm performance is likely to depend on political capabilities required to manage relationships with the government and regulatory bodies (Holburn & Vanden Bergh, 2008; Mahon & Murray, 1981). These capabilities are likely to be highly context-specific, and constitute part of what have been specified as location-bound firm-specific advantages (FSAs) (Rugman & Verbeke, 2001). As liberalization proceeds, governments and regulatory bodies slowly cease to be buffers against market forces, and, accordingly, there is a shift in emphasis away from the maintenance of relationships with regulators and towards efficient operations and business capabilities.

Domestic firms are forced to operate under new institutional mechanisms and adopt unfamiliar forms of governance (Peng & Heath, 1996). The entering MNEs possess sophisticated technological and managerial capabilities that domestic incumbents lack (Cantwell, 1989). Consequently, domestic firms need to “re-orient” themselves by making changes to their strategies, structures, technologies, systems and organizational practices/routines (Suarez & Oliva, 2005; Tushman & Romanelli, 1985). In addition, the networking capabilities of domestic firms become key success factors, as they catalyze valuable technology inflows and upgrading (McDermott, Corredoira, & Kruse, 2009). In other words, there is a fundamental change in the nature of FSAs required to generate competitive advantage as market liberalization proceeds.

The experiences of domestic firms during market liberalization in China, Eastern Europe and Latin America have been explored in the literature (e.g., Ghemawat & Kennedy, 1999; McDermott & Corredoira, 2010; Peng & Heath, 1996; Suarez & Oliva, 2005; Uhlenbruck, Meyer, & Hitt, 2003). Many of these studies describe how MNE entrants gained the upper hand over domestic firms. Such a dynamic is particularly evident in high-knowledge industries characterized by complex products, proprietary and firm-specific technologies and processes, and globally integrated value chains.

By contrast, in this paper, we ask the question: How may domestic firms in emerging economies catch up and perform well with market liberalization and large-scale entry by MNEs? Our question is prompted by the extensive literature on upgrading and catch-up processes in emerging economies (e.g., Abramovitz, 1986; Amsden, 1989; McDermott & Corredoira, 2010). The key thesis behind “catch-up” is that there is greater potential for rapid increases in productivity, the more backward the technological and other capabilities embodied in a country's resource stock (Abramovitz, 1986). This notion of catch-up can also be applied at the firm level (e.g., see Amsden, 1989; McDermott & Corredoira, 2010).

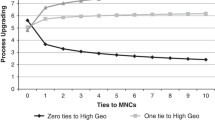

As liberalization begins, most domestic firms are likely to be technologically and managerially backward, without much variance in their capabilities and performance. As MNEs with sophisticated capabilities enter, and upgrading of the overall economy occurs through foreign direct investment and attendant spillovers, local firms in emerging economies can potentially catch up by proactively investing in upgrading their competencies. The catch-up process tends to be spearheaded by a few “leading” (large or small) domestic firms that adapt their strategies and make appropriate investments in upgrading their capabilities, diverging away from laggard firms. As the process continues, a few leaders begin to approach world standards in terms of capabilities, and a few laggards remain anchored in the old ways, but (especially with a large population, as in a highly fragmented industry) most firms make some progress. As each firm chooses its optimal level of investment in upgrading, the overall variance in firm capabilities increases (see Figure 1).

Indeed, one can visualize the catch-up process as an umbrella, whose stalk represents the capability of the average local firm and whose canopy represents the variance in capabilities of the population of local firms. As the catch-up process evolves through time, the stalk moves continuously to the right (increasing average local firm capability) and the canopy opens (increasing variance of local firm capabilities). The culmination of the catch-up process is convergence, where the stalk reaches the average capability level in advanced economies and the canopy closes again (surviving local firms are all at or close to world standards).

We study such catch-up dynamics and strategies among domestic firms in the context of the auto components industry in India during the decade (1992–2002) after economic liberalization began in 1991. The automotive industry (which includes the auto components industry), especially in a liberalizing emerging economy such as India, presents the ideal context for our study, for several reasons. First, global auto manufacturers – even Western firms – have abandoned vertical integration and have followed Japanese auto manufacturers in outsourcing components (even entire modules) and developing close, long-term parallel-sourcing relationships with a few key suppliers (Cusumano & Takeishi, 1991; Mudambi & Helper, 1998). Second, the technological sophistication and mature nature of the industry induces significant competition in any new market, so that cost competitiveness is essential for survival. Consequently, MNE entrants may need to develop local supply chains to compete successfully on a cost basis in the new markets (Humphrey, 2003; Veloso & Kumar, 2002). However, the complex, integrated nature of the end product necessitates a costly testing/qualification process. This prompts MNEs to encourage their established suppliers (or other transnational suppliers) to follow them into the new markets, instead of developing domestic firms in the host countries for the job (Humphrey, 2003; Humphrey & Salerno, 2000). In other words, domestic supplier firms may face considerable challenges in adapting and surviving (leave alone performing) with the onset of market liberalization. This is especially the case given the strong incentives for MNEs to maintain control over their respective global supply chains. Indeed, McDermott and Corredoira (2010: 311) observe that domestic supplier firms may encounter an upgrading “glass ceiling”, and even those that manage to survive may be confined to peripheral roles in the MNE auto manufacturers’ global supply chain. However, anecdotal and case-based evidence suggests that many domestic Indian auto components suppliers survived the entry of MNEs into the Indian market, and some even integrated into the global auto industry value chain. This foregoing discussion specifies the context and underlines the significance of our current study.

In the Indian auto components industry, we find that the industry environment evolved through several phases, catalyzed by the periodic policy refinements made by the Indian government after market liberalization was initiated in 1991. We hypothesize that domestic supplier firms need to adapt their catch-up strategies as their environment evolves: first, through arm's length technology licensing/collaboration or through joint ventures; then also through integration into the industry's global value chain by developing strong customer relationships with downstream firms; and, finally, by progressing to knowledge creation through internal R&D (Mudambi, 2008). Our empirical analysis of data from the Indian auto components industry during the period 1992–2002 offers support for our hypotheses.

The contributions of our study are threefold. First, our study is among the relatively few (e.g., McDermott and Corredoira, 2010) to study the upgrading and catch-up strategies of domestic supplier firms in response to market liberalization in a downstream industry. Typically, in emerging economies, such firms are relatively small, but account for significant employment. The widespread failure of such firms has the potential to create considerable disruptions and angst against MNEs or even the liberalization process itself (Dunning & Lundan, 2008). Furthermore, in studying institutional evolution and catch-up strategies, we heed Peng's (2003) advice to consider the interactions among domestic firms, MNE entrants and host governments in shaping one another's strategic choices. Second, we provide a window into the experiences of Indian firms during market liberalization. The Indian experience with liberalization is relatively underexplored in the management and international business literatures, and has the potential to offer a distinct point of comparison with the considerable work that already exists in the Chinese, Eastern/Central European and Latin American contexts. Specifically, following Spicer, McDermott, and Kogut (2000), our study emphasizes the multivalent and evolutionary nature of the liberalization process, and the associated evolution of domestic firms’ catch-up strategies over time. Finally, in studying the Indian auto components industry, we validate and extend the findings of recent studies (e.g., Humphrey, 2003; McDermott & Corredoira, 2010) on the process of integration of newly liberalized emerging-market firms into the global value chain of the auto industry, a key industry and also among the first to be liberalized in emerging economies.

The remainder of our paper is organized as follows. First, we offer a description of the Indian auto industry and its evolution over time. Next, we theorize on domestic supplier firms’ catch-up strategies over time, and the performance consequences of such strategies. Then, we discuss our data, variable measures and statistical models. After presenting the results of our analysis, we conclude by discussing key implications and speculating on the future of the Indian auto components industry.

EVOLUTION OF THE INDIAN AUTO COMPONENTS INDUSTRY

In the decades after independence in 1947, the Indian economy was characterized by a pervasive system of regulation, epitomized by the Industrial Licensing (Development and Regulation) Act (No. 65 of 1951). In addition to reserving substantial sectors of the economy for state-owned enterprises, this policy placed significant restrictions on the expansion of existing private businesses, as well as on new private start-ups. To obtain permits for undertaking or expanding business operations, particularly in lucrative sectors of the economy, firms had to interact extensively with government regulators and politicians.

The management of relationships with government bodies was a location-bound FSA (Rugman & Verbeke, 2001) that was the most important determinant of firm performance (Majumdar, 1997). This is evidenced by the fact that even the most successful domestic firms had relatively small operations outside India. Opposition to this policy of regulation was given credence by the persistently dismal performance of state-run enterprises (Jalan, 1991). The seeds of change were sown in the 1980s, beginning with very small “reforms by stealth” (1980–1984), followed by “reforms with reluctance” (1984–1991) and finally “reforms by storm” (economy-wide liberalization from 1991 onwards) (Bhagwati, 1993).

Within the milieu of changes in the overall economy, three events served as catalysts in the auto components industry's recent history and evolution: auto industry liberalization as part of wider economic liberalization, beginning in 1991; a clarification of auto policy in 1997; and a new auto policy in 2002. Accordingly, we organize our description into three successive phases of evolution, beginning with market liberalization in 1991: 1992–1997, 1998–2002 and post-2002. But, first, we offer a brief window into the pre-liberalization (i.e., pre-1991) phase of the industry, to provide additional historical context.

Pre-1991

In the 1950s, the Indian government's policy of import substitution and indigenization (of up to 95%) prompted global auto manufacturers such as Ford and GM to exit India (D’Costa, 1995). The government classified passenger vehicles as luxury goods, leading domestic auto manufacturers to focus on the commercial vehicles market. Furthermore, to promote entrepreneurial growth of the auto components industry, the government reserved a significant portion of components manufacturing for small, privately owned firms termed small-scale industries. Under this policy, from the mid-1960s, auto manufacturers were not permitted to expand their internal components-manufacturing capacity, and instead were required to purchase a number of components from these small, independent components suppliers (Singh, 2004).

In 1959, and later in 1960, incipient bodies that later became the Automotive Components Manufacturers Association of India (ACMA) and the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM) were established. These two industry associations became key sources of information on the domestic automotive industry, served as the liaison with the Indian government and potential export markets, and initiated industry-level efforts to promote quality, productivity and research (Singh, 2004). For its part, the government established the Engineering Export Promotion Council (EEPC) in 1955. Beginning in the 1960s, it also established public vocational training schools called Industrial Training Institutes (ITI) around the country to ensure a steady supply of skilled labor. In 1966, the automotive industry and the government jointly set up the Automotive Research Association of India (ARAI) to promote applied research and product development, and also to offer testing/certification services.

Notwithstanding these efforts to develop the institutional infrastructure, the Indian auto industry remained closely regulated and protected by the government and, consequently, small in size. Absent competitive pressures, domestic auto manufacturers had little incentive to perform consequential research, product development or quality improvement. They tended to choose components suppliers based on price, and seldom partnered with or assisted these suppliers (Okada, 2004). The small supplier firms, in turn, could not afford to employ well-trained graduates of the ITIs, and relied predominantly on less-skilled labor (Okada, 2004). Consequently, the auto components industry became very fragmented, with low production volumes, predominantly low-skilled labor, low technological intensity and low quality. Exports were meager, and directed primarily to developing countries in Africa and the Middle East.

With time, however, regional clusters anchored by subsidies from state governments and a critical mass of labor emerged around key domestic automakers in the West, East and South. A few capable and relatively large auto component firms, such as Dunlop, Exide, ICI, the TVS Group and India Pistons, emerged to constitute the “organized sector” of the auto components industry (Tewari, 2001). Firms in the “organized sector” sold their products directly to at least one domestic auto manufacturer, whereas firms in the “unorganized sector” were the so-called “small-scale industries”, primarily supplying inferior-quality components to the after-market (Saranga, 2009).

The government's decision in the early 1980s to permit domestic commercial vehicles manufacturers to set up new units, add capacity in auto and components manufacturing, and enter into technical/financial collaborations with foreign auto and components firms (primarily Japanese) heralded the first tentative steps towards liberalizing the auto industry. In 1983, Maruti Udyog Limited (MUL) was established as a joint venture between the Indian government and Suzuki Motors of Japan to manufacture low-priced, small cars for the growing Indian middle class. However, these attempts at liberalization were limited, with the government allowing new entry by private firms only in the auto components industry, while prohibiting such entry in the growing passenger car segment during the rest of the decade.

During this decade, prompted by the local content requirement imposed by the government and also the appreciating yen, MUL and the Japanese commercial vehicles joint ventures began to develop local supplier networks by encouraging entrepreneurial start-ups, offering technical/managerial assistance, and promoting joint ventures between their traditional Japanese suppliers and domestic firms (D’Costa, 1995; Okada, 2004). This resulted in the auto components industry – at least, the immediate supply chains of MUL and the Japanese joint ventures in two-wheelers and commercial vehicles – adopting lean manufacturing and other advanced and modern management practices (Tewari, 2001). By 1990–1991, mirroring the growth of the downstream auto industry, the auto components industry had grown to $1.49 billion in revenues (of which the “organized sector” contributed approximately $1.15 billion) from just $80 million in 1980–1981 (Singh, 2004). However, export revenues remained low, at just $125 million.

1992–1997

Significant liberalization of the auto industry began only in 1991–1992, as part of the wider liberalization of India's economy. The industry was delicensed, and technology licensing/transfer was encouraged. MNE auto manufacturers were allowed to enter the Indian auto market and set up majority-owned or even wholly owned ventures on a case-by-case basis. Large Indian firms and MNEs were allowed to take up to a 24% stake in small domestic components suppliers (Singh, 2004). Between 1992 and 1997 many MNE auto manufacturers, such as Daewoo, Daimler, Ford, Honda, GM, Peugeot and Toyota, entered the Indian market, primarily through joint venture assembly operations with domestic incumbents, and announced plans to relocate a number of global models into the Indian auto market (D’Costa, 1995).

Expecting MNE entrants to source all their components needs from domestic components suppliers, the Indian government had not allowed the import of completely knocked down kits (CKDs) or components by MNE entrants (Humphrey, Mukherjee, Zilbovicius, & Arbix, 1998, citing industry sources). In 1995, when it was clear that MNEs could not begin low-volume operations without importing CKDs and components, the Indian government signed Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) with individual MNE entrants allowing them to import CKDs and components; in return, however, entrants had to make (non-public) case-by-case commitments on production volume, local content levels and exports equivalent to CKD/components imports (Humphrey et al., 1998). The government also imposed high customs duties on imported CKDs and components until MNE entrants fulfilled their commitments. These high duties made it difficult for MNE entrants to compete on costs with MUL in the low-priced, small car segment. Therefore they focused primarily on the smaller markets for mid-sized and high-end cars.

TELCO (now Tata Motors) and Mahindra & Mahindra, two dominant domestic manufacturers of commercial vehicles, entered the passenger car segment during the early 1990s with multi-utility vehicles, and later with small cars. The incumbent domestic car manufacturers, Premier and HM, responded by upgrading their technology and quality, and expanding their offerings in the mid-sized car segment. All the domestic auto manufacturers faced stiff competition from the advanced models offered by MNE entrants.

These developments prompted significant changes in the auto components industry. A few MNE components firms followed MNE auto manufacturers into India by establishing wholly owned subsidiaries. Some others formed joint ventures with the more capable domestic components suppliers to produce critical components needed by MNE auto manufacturers. However, most of them were content with licensing technologies to domestic components firms that wanted to upgrade their technology and productivity. Even relatively small domestic components firms began hiring well-educated graduates of the ITIs, instituting training programs and new work practices, and relying increasingly on professional managers (Okada, 2004); the institutional infrastructure that the government helped establish in the 1950s and 1960s began paying off.

By 1996–1997, auto components industry revenues had increased to nearly $3 billion, with $0.33 billion derived from exports. However, components exports were targeted primarily at the lower-quality after-markets, with only a few domestic firms such as Sundaram Fasteners (a member of the TVS Group) and Wheels India exporting low volumes to MNE auto manufacturers or Tier 1 firms (Humphrey et al., 1998).

1998–2002

In 1997, the government announced a uniform policy (in contrast to the case-by-case MOUs signed in 1995) requiring new entrants to establish manufacturing (not just assembly) operations in India. This policy imposed several requirements on new entrants:

-

1)

an aggressive schedule of 50% local content in the first three years, rising to 70% by the fifth year;

-

2)

foreign exchange neutrality by requiring entrants that imported CKDs and semi knocked-down kits (SKDs) to export an equivalent amount, beginning with the third year;

-

3)

an investment of at least $50 million to set up wholly owned subsidiaries (Singh, 2004; Tewari, 2001).

Progressively, the government also imposed emission norms equivalent to Euro 1 and Euro 2 emission standards to encourage domestic firms to upgrade the engine technology in their models.

Several MNE Tier 1 components suppliers entered the Indian market through wholly owned subsidiaries or joint ventures with a few domestic components firms, and cut back on licensing their technologies to other firms.Footnote 1 However, the relatively high investment required for wholly owned subsidiaries, competition and pricing pressures in a low-volume market, and the aggressive local content requirements, meant that MNE auto manufacturers and MNE Tier 1 firms had to develop local sources for a number of components. To ensure that their global standards were met in the Indian market, MNEs had to engage in close interactions and joint efforts with local suppliers to improve quality and productivity. Domestic auto manufacturers also began establishing closer relationships with their suppliers, in contrast to their earlier arm's length and price-based dealings (Okada, 2004).

Beginning in the late 1990s, both MNE and domestic auto manufacturers began to rationalize their respective local supply chains and require their suppliers to locate close to assembly operations (Humphrey et al., 1998). With time, the Indian auto components industry became stratified more formally into “tiers”, with Tier 1 being constituted by MNE components suppliers, their Indian joint ventures and the more capable domestic components suppliers (Okada, 2004). In addition, driven by subsidies offered by respective state governments, three major auto clusters crystallized around major auto manufacturers in the North (Delhi/Gurgaon), West (Pune) and South (Chennai) of India.

Even though demand, production volumes and the variety of models had grown – especially after private banks such as ICICI and HDFC began financing car purchases in late 1999 – the Indian auto industry lagged in size behind those in Korea, China and Brazil (among the emerging economies). The Indian auto components industry was commensurately small at $4.5 billion in 2001–2002. As tierization became more formal and competition increased, many domestic components suppliers turned to exports. Accordingly, revenues from exports increased, but still were low at just $0.58 billion in 2001–2002.

Post-2002

In 2002, the government announced a new auto policy to make India a major source of small cars for the global market, and also an Asian hub for auto components. Under this policy, the government further liberalized the auto and auto components markets by permitting 100% foreign ownership without attendant local content and minimum investment requirements. In 2001, it had already removed the equivalent export obligations to balance CKD and components imports.

In 2003, in partnership with the industry and academia, the government set up a Core Group on Automotive R&D (CAR) to establish priorities for the future, and approved funding for an industry proposal to establish two new, advanced automotive testing/certification facilities and to upgrade the two existing ones. Beginning in 2004, the government also began reducing tariffs and customs duties on key raw materials such as steel, and, with the 2005 national budget, allowing auto manufacturers and components firms to take a weighted deduction of 150% of their R&D expenses.

These developments prompted many MNE auto manufacturers and components firms to increase their ownership/control of joint ventures, or to set up wholly owned subsidiaries in India. Therefore a number of joint venture partnerships began giving way to either 100% MNE or 100% domestic ownership. In addition, with 100% ownership, MNEs began to employ an aggressive technology-driven strategy and to integrate their Indian subsidiaries with their global operations. Furthermore, absent local content requirements, a few MNE auto manufacturers such as BMW began relying on CKDs instead of sourcing components locally. For their part, domestic supplier firms also began to use overseas acquisitions (outward FDI) to obtain more advanced technologies and faster growth, instead of relying just on organic growth and competency development through in-house R&D. The free trade agreement signed in 2004 with Thailand presented growth opportunities for Indian auto components firms, even as it increased the threat of competition from ASEAN countries. Furthermore, free trade agreements between other nations – for instance, the agreement between EU nations and South Korea – raised the prospect of MNE firms shifting some production away from India.

Summary

In sum, the Indian automotive industry appeared to have evolved in several phases as liberalization progressed and the government fine-tuned its auto policy. At the beginning, the main policy objectives presumably were to attract MNE entry by removing regulatory constraints, and to alter the incentives of domestic business groups that were biased against advanced technologies and innovation by a lack of competitive pressure (Mahmood & Mitchell, 2004). During the next phase, the government discouraged CKD and components imports by clarifying its auto policy and requiring new MNE entrants to commit to local manufacturing and aggressive indigenization, thereby contributing to the upgrading and growth of the domestic auto industry. As growth and consolidation progressed, the government liberalized further by removing many requirements imposed on MNEs, reducing customs duties on key inputs, and offering strong incentives for local R&D. During this third phase, the key policy objective was to facilitate the integration of domestic industry with global markets, and thereby sustain its growth and competitiveness.

DOMESTIC FIRMS’ CATCH-UP STRATEGIES AND PERFORMANCE

We begin by explicitly defining the boundaries of our theory. Our research context is market liberalization of a relatively mature industry (by global standards) in an emerging economy – the auto/components industry in India during the 1990s – that had been largely isolated from advanced technologies and global markets for many decades. Our country of interest, India, shares characteristics with other emerging economies, but also offers a relatively unique research setting. India's economy has been mixed, that is, characterized by the coexistence of state-owned and private firms, since independence in 1947. Further, the process of market liberalization in India was relatively gradual, with periodic fine-tuning by the government based on political, institutional and market considerations. Such a gradual process has several common aspects with the mass privatization efforts in Central/Eastern European nations (e.g., Ekiert & Hanson, 2003; Spicer et al., 2000). However, the relative uniqueness of India as a mixed economy, in our view, can serve as a point of comparison and contrast with market liberalization and domestic firms’ catch-up strategies in countries in Central/Eastern Europe, Latin America and China.

Our industry of interest – the auto/components industry – is mature, and capital intensive with significant scale economies, and produces a complex product whose development is costly and time-consuming. Auto manufacturers have strong incentives to persist globally with their erstwhile suppliers, and tend to introduce existing or derivative products instead of developing new products from scratch for liberalizing markets in emerging economies (Humphrey, 2003; Humphrey & Salerno, 2000). Many manufacturing industries that produce complex products also exhibit these characteristics. Finally, domestic firms whose catch-up strategies we study were small and backward, catering predominantly to domestic markets, and by no means globally competitive when market liberalization began. Such were the initial conditions for domestic firms in most emerging economies when economic liberalization efforts began.

Theory and Hypotheses

For domestic industries and firms in emerging-market economies, the onset of economic liberalization typically ends many decades of isolation from advanced technologies and global competition. For the governments in these economies, a key objective of liberalization is to attract MNEs to invest and assist in the upgrading of the country's human and technological capabilities (Ivarsson & Alvstam, 2005). Such upgrading may occur due to intentional transfers of technical and managerial competencies by MNEs through formal mechanisms such as technology licensing/collaboration and joint ventures with domestic firms, and knowledge transfers to subsidiaries. Alternatively, it may occur through unintentional spillovers due to labor mobility, leakage of intellectual property and imitation by domestic firms, or vertical linkages (Alcacer & Chung, 2007; Blomström & Kokko, 1998; Cantwell, 1989; Chung, 2001). In addition to these transfers and spillovers from MNEs, domestic firms may proactively seek to acquire and upgrade their competencies to become competitive in an increasingly open market.

In the initial years of the liberalization process, the host government is likely to hold few bargaining chips, and therefore to offer a number of concessions to entice MNEs to enter (Dunning & Lundan, 2008). Thus, for MNEs, newly liberalizing economies offer opportunities at institutional entrepreneurship through market entry and the shaping of still-evolving host-country institutions in their favor (Cantwell, Dunning, & Lundan, 2010). They afford potentially large new markets for their products, as well as access to location-bound or country-specific advantages (CSAs), that is, complementary assets such as natural resources, cheaper factors of production or distribution channels ( Cantwell & Mudambi, 2011; Dunning, 1988) that they can “bundle” with their own FSAs.

In such a case, the transactions costs incurred by MNEs in gaining access to complementary CSAs and integrating these with their own FSAs determine their entry modes and investment levels in the new market. Hennart (2009) adds another dimension to this consideration, arguing that the transactions costs incurred by domestic firms in gaining access to and combining MNEs’ FSAs with their own CSAs are as important as the costs incurred by the MNE in gaining access to complementary CSAs. In other words, the most appropriate MNE entry mode and organization is one that maximizes the total rents accruing from the bundle of FSAs and CSAs (Chen, 2010).

In many manufacturing industries, the FSAs possessed by the MNE are likely to be in the form of advanced technologies, products, processes and organization. Although domestic firms lack technological competencies when liberalization begins, they may possess valuable knowledge-based complementary assets (CSAs), such as market or distribution-related knowledge and expertise (e.g., a network of dealerships in the auto industry). Contracting in the open market for distribution services or acquiring them outright may be difficult for MNEs (Hennart, 2000). The preferred mode of entry for an MNE when both MNE FSAs and local firms’ CSAs are difficult to transact is an equity joint venture (Hennart, 2009).Footnote 2 However, MNEs may lack the market knowledge to identify potential partners or targets for partial acquisition. Therefore they may have to rely on noisy signals of domestic firms’ competencies, such as firm size (Henderson & Cockburn, 1994) or prior performance. Entry through equity joint ventures may also help mitigate the risks due to the uncertain institutional environment (Meyer, 2001; Peng, 2003).

Mature industries such as the auto industry are often among the first to be liberalized. These industries are characterized by standardized components and processes, proprietary and OEM-specific technologies. There is also a growing trend among firms in many industries to maintain close relationships with only a small group of suppliers (Goffin, Lemke, & Szwejczewski, 2006; Mudambi & Helper, 1998), and to maintain close control over their globally dispersed supply chains. For the above reasons, MNEs may find it efficient to persist with extant suppliers in these new markets, and opt to import CKDs and components instead of developing local sources. Or, if customs duties and tariffs imposed by the host government on imports are high, they may encourage extant suppliers to follow them into the host country.

Extant global suppliers do not need access to local distribution expertise or market knowledge, since this aspect of the supply chain is handled by the auto manufacturers. Following the logic of Hennart's (2009) model, setting up wholly owned subsidiaries would be the appropriate option for them. This option, however, may not be attractive if slow market growth precludes scale economies, or if the host government imposes ownership limits or minimum investment requirements on MNE entrants. In such cases, these global suppliers may have to resort to a range of entry modes, such as equity joint ventures, technology licensing agreements (i.e., sale of technology) or technology collaborations with domestic firms (e.g., equipment or designs). For critical components – where control over intellectual property and operations is essential – global supplier firms may opt for equity joint ventures. For relatively standard or simple components, the time, effort and capital required to form and sustain equity joint ventures may be difficult to justify. In such cases, global supplier firms may prefer arm's length technology licensing or collaboration.

For domestic firms, equity joint ventures and arm's length technology licensing/collaborations offer the opportunity to catch up by upgrading their technological competencies.Footnote 3 However, domestic firms (even those engaged in joint ventures with MNEs) may face significant difficulties in assimilating and exploiting licensed technologies, owing to a lack of financial capital, appropriate human capital, or appropriate organizational structures and routines (Van den Bosch, Volberda, & De Boer, 1999). In addition, they would have to accumulate buyer-specific know-how, build the required complementary assets and develop their absorptive capacities (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Kogut & Zander, 1992; Lane & Lubatkin, 1998). Such investments, although perhaps critical to survival in the long term, are likely to have a negative effect on domestic firms’ contemporaneous performance. Firms that don’t upgrade – either because they are incapable of benefiting or because they cannot afford to do so – do not incur associated costs, and may survive in the short term by continuing to service the shrinking market for cheap, low-quality products. Capable firms that do upgrade through licensing or joint ventures (and can benefit) will face short-term costs and a negative influence on their contemporaneous performance. Thus upgrading through technology licensing or joint ventures is likely to have a counterintuitive effect on domestic firms’ contemporaneous performance in the early years of market liberalization. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1:

-

During the early years of market liberalization, upgrading through technology licensing and technical collaborations (arm's length or through joint ventures with MNEs) becomes the dominant catch-up strategy for domestic firms. The (short-run) effect of this strategy on contemporaneous performance of domestic firms is negative.

With time, the institutional framework to support open, efficient markets for assets and firms becomes stronger. Furthermore, as MNEs gain knowledge of the host-country market and also develop the competency to effectively bundle their FSAs with complementary CSAs, their need for local partners diminishes (Fang & Zou, 2010). As per Hennart's (2009) model, MNEs FSAs are still difficult to transact whereas, now, complementary CSAs become much easier to transact. In other words, the preferred mode of organization for MNEs shifts to wholly owned subsidiaries (unless proscribed by the host government). Accordingly, MNEs may seek to acquire domestic firms or buy out their joint venture partners to secure full control over operations in the host country (Boisot & Child, 1999; Cantwell & Mudambi, 2005; Makino & Delios, 1996; Meyer, 2001; Peng, 2000, 2003). Indeed, as has happened in many liberalized economies, these developments may hasten the demise of domestic industries, replacing these over time with a constellation of dominant MNEs supported by a few domestic firms playing peripheral roles.

Clearly, the preferences of MNEs and their global suppliers are not consistent with the host government's objectives. The host government may well realize that MNE entrants need to be induced to serve the government's objectives (Evans, 1979), through policy changes and initiatives that can be viewed as “leading the market” (Mahmood & Rufin, 2005: 340). Specifically, the host government may (re)impose requirements on MNEs, such as minimum investment levels, local manufacturing, aggressive indigenization schedules, and even limits on ownership, to encourage technology transfer and assistance to domestic firms. The government may also impose quantitative restrictions or high customs duties on imported CKDs and components. These changes make MNEs’ preferred strategies difficult (or costly) to pursue, and may induce them to assist more actively in upgrading the host country's technology, firms and human capital in return for continued market access. Given these restrictions, MNEs may be forced to undertake vendor development efforts. Vendor development efforts typically require the MNE to assume the challenge of transferring tacit and sticky know-how to the domestic firm, and then ensuring that the domestic firm also develops the competencies to assimilate and exploit these technologies productively.

Such vendor development efforts may enable domestic firms to better assimilate licensed technologies and upgrade their manufacturing competencies. However, in a globally integrated marketplace dominated by MNEs, manufacturing competencies (although important) do not add as much value as acquiring marketing knowledge or creating new knowledge through R&D (Everatt, Tsai, & Cheng, 1999; Morck & Yeung, 1991; Mudambi, 2008). Therefore it is incumbent on domestic firms to progress beyond just acquiring manufacturing competencies.

The ability of domestic firms to progress further with their catch-up efforts depends on how close a relationship they are able to forge with downstream firms, that is, their customers. Repeated, frequent interactions facilitate the co-development of matching organizational structures and processes between partnering firms (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998), and increase the volume and granularity of information flows between them (Uzzi, 1996). In turn, this generates trust and a greater appreciation of each other's challenges and strengths, thereby facilitating the transfer of tacit knowledge and learning (Dyer & Singh, 1998; Martin & Salomon, 2003). Over time, a virtuous circle emerges wherein increasingly relation-specific investments enable partners to recognize additional opportunities for collaborating and strengthening existing ties (Gulati & Gargiulo, 1999).

For domestic firms, close ties with their customers (especially MNEs) enable them to gain deeper insight into and first-hand experience of customer needs, and to combine their contextual knowledge and upgraded technical competencies to better service these needs. For instance, they can implement mechanisms such as concurrent design/engineering, quality circles and synchronized operations based on real-time data. Such mechanisms lead to lower costs, higher quality and potentially higher rates of innovation. Furthermore, domestic firms can benefit from the indirect ties that their MNE customers have with other parties (Gulati & Gargiulo, 1999; Uzzi, 1996). For instance, belonging to a global production and innovation network may eventually enable domestic firms to access a much larger stream of opportunities, even though they may be able to capture only a small share of these rents (Mudambi, 2008). In this context, Dyer and Nobeoka (2000) describe in detail the mechanisms that enabled suppliers in Toyota's production network to benefit from strong ties with Toyota and the resultant knowledge-sharing with network participants. Participants in Toyota's production network shared a strong network identity that facilitated the emergence of norms for mutually beneficial coordination, communication and learning. Using this shared identity as leverage, Toyota created network-level processes for knowledge-sharing such as a supplier association, an operations management consulting division to solve difficult operational problems, voluntary study groups or learning teams, and inter-firm employee transfers. Indeed, McDermott and Corredoira (2010) report that even a few relational ties with MNE auto manufacturers enabled domestic components firms in Argentina to survive.

The time, investment and effort required on the part of MNEs to develop local supplier partners are likely to exhibit powerful “lock-out effects” (Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000: 210). The creation of strong relationships by MNEs with one (or a set) of domestic firms might preclude relationships with other firms, thereby locking late movers out of vendor development efforts permanently. Such lock-outs become especially harmful to the domestic firms involved, given the trend in the auto industry of forging strong ties with just a few suppliers globally (Mudambi & Helper, 1998).

MNEs may be concerned about the extent of investment required to develop local suppliers to acceptable levels of competence (Meyer, Mudambi, & Narula, 2011). They may also be wary of opportunism on the part of domestic firms, owing to the relatively weak intellectual property regimes in emerging economies (Kogut, 1988). Therefore domestic firms early on may need to mitigate these concerns by aggressively investing in learning and technology assimilation. In addition to credibly demonstrating that they possess “receiver competence”, that is, the ability to receive and utilize the transferred technologies and tacit knowledge (Mudambi & Navarra, 2004: 389), the development of customer-specific technological expertise and co-specialized assets may allay suspicions of potential opportunism (Teece, 1986).

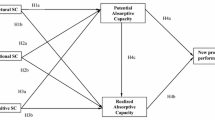

In sum, continued efforts at technology upgrading (i.e., developing technical knowledge) and the development of strong customer relationships (i.e., developing marketing knowledge) will both become critical to performance (Mudambi, 2008). Accordingly, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 2:

-

As liberalization proceeds, developing strong customer relationships and integrating into the industry value chain become part of the optimal catch-up strategy for domestic firms. Both catch-up strategies (i.e., technology licensing/collaborations and customer relationship development) have a positive effect on the performance of domestic firms.

Based on market growth, adjustments made by MNEs, and resultant consequences for domestic industry and firms, the host government may repeatedly fine-tune the policy regime over time. As Peng (2003) noted, such dynamics may result in a more gradual institutional transition to an open-market economy and offer much-needed time for domestic industries and firms to adjust. However, as upgrading of domestic industries and firms proceeds over time, it becomes increasingly difficult for host governments to “lead the market” with a relatively heavy hand. Indeed, Mahmood and Rufin (2005) argue that “economic decentralization” is more conducive to innovation, especially when technology development in the host country nears the technology frontier. Furthermore, at this stage, the host government's interest would be to facilitate the integration of domestic industries and firms into the global marketplace for continued growth. Accordingly, there is a strong incentive for the host government to relax restrictions that it had earlier imposed on MNE entrants’ operations.

At this stage, domestic firms may have to upgrade their competencies further to survive and compete in the global marketplace. Domestic firms may have to develop competencies in internal R&D instead of using technology licensing as a substitute (Bell & Pavitt, 1993; Kumar & Siddharthan, 1994). Experimentation and first-hand experience need to supplement observational learning from their partners (Uhlenbruck et al., 2003).Footnote 4 Such internal R&D increases local absorptive capacities even further (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990), enabling them to develop know-why and know-what essential for new product development and innovation (see Garud, 1997; Kim, 1998; Kogut & Zander, 1992).

Such a choice by domestic firms would further spur MNE efforts to gain control over their ventures, as the institutional environment becomes capable of supporting open, rule-based market transactions (Cantwell & Mudambi, 2011; Peng, 2003). This imperative to establish regional beachheads and also integrate them more tightly with their global operations may translate into attempts to rationalize their local supply chains. They may become more selective in licensing their technologies, and retain close relationships only with a few domestic firms with the capability to become full partners in product and process development. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3:

-

As liberalization matures, upgrading internal R&D to create new knowledge becomes part of the optimal catch-up strategy for domestic firms, in addition to technology licensing/collaborations and customer relationship development. All three catch-up strategies will have a positive effect on the performance of domestic firms.

Our Theory and Hypotheses in Context

Now, we place our theory and hypotheses in the context of the Indian auto components industry. We noted earlier that the Indian government made two significant policy revisions after liberalization began in 1991: a clarification of the auto policy in 1997, and the new auto policy in 2002. At the beginning, fewer restrictions were placed on foreign firms as the Indian government tried to entice MNEs to enter. We call this period (1992–1997) the transition phase, during which MNEs began entering the market, the government rectified “unanticipated” problems with its policy on MNE entry/operations, and domestic firms began adapting to open market competition. The formal clarification of the auto policy in 1997 signaled the imposition of a more restrictive regime to induce MNE entrants to help upgrade domestic firms and industries, in return for market access. We term this period (1998–2002) the consolidation phase, during which domestic firms attempted to build on their upgrading, and MNEs adjusted to the policy clarifications and began consolidating their position in the Indian auto market. Finally, with the new auto policy of 2002, the Indian government removed most requirements and restrictions on MNEs, to facilitate the integration of the Indian auto industry into the global marketplace. Accordingly, we term this post-2002 period the global integration phase. In Table 1, we highlight key events in the evolution of the Indian auto components industry. In Figure 2, we represent our theoretical model in the context of the Indian auto components industry's evolution after liberalization began in 1991. Such an evolutionary and multivalent approach to liberalization is consistent with the findings of studies of the mass privatization efforts undertaken by Eastern/Central European countries (Ekiert & Hanson, 2003; Spicer et al., 2000).

DATA, VARIABLE MEASURES AND MODELS

In our theoretical model, we hypothesize how the catch-up strategies of domestic firms are likely to evolve as market liberalization progresses, and influence their performance. Although our theory development relates to industry evolution and catch-up strategies in three successive phases, our empirical analysis is confined to the first two phases, that is, the transition phase (1992–1997) and the consolidation phase (1998–2002). In other words, our empirical analysis is restricted to the first two panels of Figure 1, that is, the process whereby the population of local firms is transformed from Distribution I into Distribution II, and the catch-up strategies that distinguish between and determine the performance of leading and laggard domestic firms. As the process of catch-up continues, the distribution of local firms begins to change again, as laggard firms either exit or accelerate their investments in technology, resulting in a return towards lower variance of capabilities in the local firm population (with a higher mean). However, data limitations do not allow us to explicitly examine this phase. Finally, the logical culmination of catch-up is convergence, whereby the capabilities of local firms match world standards (represented by Distribution III in Figure 1); this endpoint is still in the future for the Indian auto parts industry.

We abstracted firm-level data for the period 1991–2002 on all Indian auto components firms listed in the Prowess database. Prowess, a database maintained by the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), India, contains detailed firm-level data on over 10,000 large and medium-sized Indian firms, comprising all firms traded on India's major stock exchanges and also state-owned firms. We obtained data on technology licensing, technical collaborations and financial collaborations for our sample of firms from CapEx, yet another database maintained by CMIE that tracks collaborations and investment projects in India, beginning in 1992. Our final sample was an unbalanced panel, and had 1271 firm-year observations for the 11-year period between 1992 and 2002. The auto components firms in our sample were predominantly Indian-controlled (93–94%) and accounted for approximately 66% (in the early years) to 85% (in the later years) of total annual industry revenues, as reported by ACMA.

In addition to the above archival data, we conducted interviews with senior executives in seven auto components firms, three of them Tier-1 suppliers and the rest Tier-2 suppliers to auto manufacturers. These firms ranged in annual revenues from US$4.9 million to US$275 million, and in size from 136 employees to over 3000; they differed in ownership from wholly Indian-owned to foreign-owned and joint ventures; and they had a representative customer base among domestic and MNE auto manufacturers. In addition, to get the customers’ perspective, we interviewed three auto manufacturers (both MNE and domestic) operating in India. Our interviewees at these ten firms were industry veterans, who had spent an average of 20 years in the auto/components industries, and occupied senior positions ranging from Assistant General Manager and Director of Quality to President and Managing Director. Interviews ranged from 1.5 hours to 2 hours each. We began our interviews with broad, open-ended questions on the changes that had occurred in the Indian auto and components industries since liberalization began in 1991, how these changes had affected their firms’ behaviors, industry critical success factors, emerging industry trends, and the potential consequences of these trends for their firms. As an interview progressed, we delved deeper into specific issues, such as the firm's behavior with regard to technology licensing, in-house R&D and the nature of their relationships with upstream/downstream firms. Our intention was not to develop theory based on these qualitative data. Instead, it was to gain a broad perspective on the industry and to validate our empirical results, where possible. We use these data only to provide additional context for our empirical results.

Variable Measures

We measured key variables as follows.

Firm performance (Performance)

Our dependent variable is firm performance. We measured the performance of domestic auto components firms using return on assets (ROA). As our sample comprised both publicly traded and privately held firms, we were not able to use return on equity (ROE) as an alternative measure of firm performance.

Technology upgrading (TechLicensing)

We measured domestic firms’ investments in technology upgrading using their reported royalty expenses over revenues for each year.Footnote 5

Strength of customer relationships (Tier, FinCollab)

We measured the closeness of domestic firms’ relationships with their customers using two measures. First, we employed the tier system (Tier) commonly used in the auto industry as a measure of the strength and quality of relationships between auto components firms and auto manufacturers. As per the tier system, a firm that supplies directly to auto manufacturers (i.e., OEMs) is considered as belonging to Tier 1, while a firm that supplies to Tier 1 firms is considered as belonging to Tier 2, and so on. A number of studies in the auto industry (e.g., Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000; Mudambi & Helper, 1998) have described the close, beneficial ties between Tier 1 suppliers and auto manufacturers. Accordingly, we expect that Tier 1 suppliers will have stronger and higher-quality relationships with auto manufacturers than lower-tier suppliers. Furthermore, as we noted earlier, 93–94% of our sample comprises Indian-controlled firms, significantly mitigating the potentially confounding effects due to the inclusion of MNE-controlled Tier 1 firms in such an analysis. As information on tier was not readily available from public databases such as Prowess, we undertook a detailed study to categorize our sample of firms by tier.Footnote 6 We then created a dummy variable with value 1 if a firm was categorized as Tier 1, and 0 otherwise. As evident from Tables 3 and 4, over 70% of the domestic components firms in our sample were categorized as Tier 1 during both the 1992–1997 and 1998–2002 phases. However, we note the qualitative difference between Tier 1 firms supplying primarily domestic auto manufacturers during the early 1992–1997 phase, and Tier 1 firms with upgraded technologies supplying both MNE and domestic auto manufacturers after MNE entry during the later 1998–2002 phase.

Second, we collected data on financial collaborations between MNEs and domestic components firms from CMIE's CapEx database. The underlying logic for this measure is that MNEs are likely to favor domestic firms in which they have a financial interest when making decisions on technology transfer or supplier relationships. We created a dummy variable, FinCollab, with value 1 if a domestic firm had financial collaborations with MNEs during a specific year, and 0 otherwise.

Knowledge creation/provision (R&D)

We measured domestic firms’ capabilities in knowledge creation using their respective R&D intensities, that is, R&D expenses over revenues for each year. We recognize that R&D intensity is an input measure, and does not necessarily imply effective knowledge creation. However, the linkage between such input measures and output measures such as patents or citation counts is typically strong (Hagedoorn & Cloodt, 2003).

In addition, based on our reading of the literature and knowledge of the industry context, we collected data on the following macroeconomic, industry-level and firm-level variables to control for other influences on domestic firms’ performance:

-

GDP growth (GDPgrowth), measured as the percentage growth in India's GDP in each year.

-

MNE market share (MNEshare), measured as the MNE auto manufacturers’ share of the Indian auto industry in each year. We used this variable to account for the influence that MNEs had over the Indian auto industry and, by implication, the auto components industry.

-

Firm size (Size), measured as the natural logarithm of domestic firms’ revenues in each year.

-

Firm age (Age), measured as time elapsed since the domestic firm's founding.

-

Firm market share (Marketshare), measured as the ratio of domestic firms’ revenues and the industry's total revenues for each year.

-

Firm exports (Exports), measured as the domestic firm's revenues from export sales.

-

Complexity of domestic firm's products (ProdComplexity), operationalized as a dummy variable with value 1 if the firm's products were categorized as highly complex, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 7 We included this variable as a control, given Hoetker's (2005) finding that firms tended to choose suppliers for innovative components based more on familiarity than on their technological competence.

-

Firm location (Location), operationalized as a dummy variable with value 1 if the domestic firm was located in one or more of the three auto clusters in India, and 0 otherwise. Geographic location within an industry or regional cluster has well-documented benefits (Okada & Siddharthan, 2007; Saxenian, 1994). In addition, Dyer (1996) found that co-location of suppliers and auto manufacturers facilitated closer coordination and faster learning, thereby conferring an advantage on the entire production network.

-

Firm ownership (Ownership), operationalized as a dummy variable with value 1 if a firm was Indian-controlled, and 0 if it was MNE-controlled. Joint ventures with MNE firms in which the Indian partner had majority ownership were considered to be Indian-controlled.

In Table 2, we present the definitions of all our variable measures. In Tables 3 and 4, we present summary statistics and correlations of variables corresponding to the 1992–1997 phase and 1998–2002 phase respectively. We acknowledge the large and statistically significant correlation between the two control variables, Size and Marketshare. We, however, decided to include both variables in our models, because each has different theoretical implications as controls, Size being clearly a firm-level control and Marketshare also implicating the firm's competitive position vis-à-vis rivals. We calculated the variance inflation factors for coefficient estimates in our various models, and found these to be well within the prescribed cut-off value of 10.

Models

We estimated separate fixed-effects models for the transition phase (1992–1997) and for the consolidation phase (1998–2002) of industry evolution during market liberalization. We ran heteroskedasticity-consistent fixed effects estimates, which automatically adjusted for differences in group-specific variances. We performed the Hausman test to compare the fixed-effects specification against the random-effects specification in terms of consistency and efficiency. The results of the test did not support the random-effects specification.

During the initial years of liberalization, MNEs entering an unfamiliar market may use variables such as Performance, Size and R&D of domestic supplier firms during prior years as signals to identify potentially valuable partners with whom to engage in joint venture or licensing arrangements. To account for such potential endogeneity, we used a two-stage fixed-effects model specification to estimate the performance implications of domestic firms’ catch-up strategies during 1992–1997. In the first stage, we estimated TechLicensing in the current period as a function of Performance, Size and R&D in the prior period. Then, we used the predicted value of TechLicensing from the first stage in the following model to estimate performance of domestic firms during the transition phase (1992–1997):

Although we explored a number of theoretically plausible interactions among key variables – for instance, between TechLicensing and Exports, between TechLicensing and R&D, between TechLicensing and Marketshare, and between TechLicensing and FinCollab – none was statistically significant.

With time, the extent to which domestic supplier firms forge strong relationships with their customers (i.e., the variable Tier) may be determined endogenously by technology upgrading during the prior period (i.e., TechLicensing and R&D during the period), firm size (i.e., Size), the complexity of the products they offer (i.e., ProdComplexity) and the location of these firms close to their customers (i.e., Location). Again, to account for potential endogeneity, we used the so-called two-stage predictor substitution (2SPS) approach (Lee, 1979) to estimate the performance model for the consolidation (1998–2002) phase. In the first stage, we estimated Tier using an unconditional maximum likelihood logistic regression model of the above variables, and then used the corresponding predicted values of Tier in the performance model:

Again, we explored a number of theoretically plausible interactions among key variables, but only one interaction (TechLicensing × FinCollab) was marginally significant at p<0.10.

ANALYSIS RESULTS

Table 5 presents the results of our analysis on the performance consequences of domestic supplier firms’ catch-up strategies during the two phases (1992–1997 and 1998–2002). We do not report the first stages of the respective two-stage models, because they are not central to our theoretical arguments; nor do we report models with interaction terms whose coefficients were not statistically significant.Footnote 8

Determinants of Performance during the Transition Phase (1992–1997):

Model 1 offers support for our Hypothesis 1, that domestic firms will catch up through technology licensing and technical collaborations (both arm's length and through joint ventures) as the dominant strategy during the initial years of market liberalization, and that such a strategy will be detrimental to their contemporaneous (i.e., short-term) performance. To MNE entrants unfamiliar with the newly open Indian market, domestic firms’ aggressiveness in upgrading their technological capabilities would serve as a credible signal of their commitment to become dependable local sources of components. Furthermore, the auto industry executives whom we interviewed revealed that most MNE auto manufacturers insisted that domestic supplier firms either enter into joint ventures with their global supply chain partners (especially for critical components) or license relevant technologies from them. An executive at a relatively capable domestic components firm stated that Indian auto manufacturers were more willing to trust them with design and development than MNE entrants that had to undertake a long and costly qualification process. However, this executive conceded that technology licensing and joint ventures were much quicker ways for domestic firms to catch up, especially when new product development would just involve “reinventing the wheel” on mature, firm-specific technologies and components. Indeed, the survival of many auto manufacturers with wide product portfolios in the relatively low-volume Indian market required flexible governance structures and technology alliances between MNE entrants and low-cost domestic suppliers (D’Costa, 2004).

Not surprisingly, GDP growth and MNE entrants’ auto industry market share (MNEshare) were positively and significantly related to performance. Indeed, economic growth and MNE entry – associated with growth of the auto components industry – no doubt increased the opportunities available for all domestic firms. In addition, domestic firms’ size (Size) and market share (Marketshare) were also positively and significantly related to their performance. Larger domestic firms, and those with an already established competitive position in the marketplace, probably possessed the stability and slack resources to tide them through the transition phase; moreover, MNE entrants may have used these characteristics as signals of domestic firms’ stability and capabilities (Ivarsson & Alvstam, 2005). Firm location (Location) was also significantly and positively related to performance. Location of domestic firms in the three auto clusters gave them some advantage, as MNEs located their operations in or near these clusters to take advantage of the pre-existing infrastructure, labor pool and subsidies offered by the respective state governments.

Domestic firms’ revenues from exports, though, were significantly but negatively related to performance. When the liberalization process began, domestic firms were exporting small quantities of cheap, low-quality components to less developed markets such as Africa and the Middle East, and to the very low-end after-market in a few developed countries. However, as domestic firms upgraded their competencies, there was a slow but sure shift to exports of quality components to MNE auto manufacturers and global Tier 1 components firms. This shift, according to industry executives, required domestic components firms to tackle serious challenges. For instance, these firms had no prior exposure to designing quality components for different environmental conditions; nor did they have a good understanding of the transportation infrastructure, logistics, packaging and liabilities of exporting to relatively developed markets. The upfront investments and higher inventory levels required to service these export markets increased their costs significantly, making them uncompetitive in the growing domestic market. Indeed, several executives opined that most domestic firms will find it difficult to balance the demands imposed by exporting with those imposed by cost considerations in the domestic market. Only domestic firms with excess capacity or those that secured opportunities through their MNE customers or partners seriously considered export sales.

Determinants of Performance during the Consolidation Phase (1998–2002):

Models 2a and 2b offer support for our Hypothesis 2. First, they support our contention that technology upgrading through licensing and technical collaborations would continue to be a catch-up strategy for domestic supplier firms, and that it would influence performance positively during the consolidation phase. In addition, our results (across Models 1, 2a and 2b) demonstrate that the development of strong customer relationships and integration into the industry value chain will follow-technology upgrading as a catch-up strategy, and will also become critical for performance during the consolidation phase.Footnote 9

Our interviews with industry executives help explain the positive effect of strong customer relationships (represented by the well-known auto industry indicator, Tier 1 supplier status) on performance, especially after the entry of MNE auto manufacturers. Executives confirmed that both domestic and MNE auto manufacturers were well aware of domestic suppliers’ technology licensing and collaborations, and used these in choosing their own suppliers. They also described how close Tier 1 relationships (especially with MNE auto manufacturers) were instrumental in gaining preferential access to technologies and “persistent attention and second chances” when they encountered operational difficulties. One executive explained how auto manufacturers were ready to “hold our hands and offer assistance in various aspects, including technical and process-related assistance, financial and managerial assistance, help in materials procurement and tooling, and even arranging tie-ups with appropriate technology providers”. Further, domestic Tier 1 firms enjoyed more opportunities and better scope for the absorption of licensed technologies and best practices (see McDermott & Corredoira, 2010). For instance, once domestic Tier 1 firms developed “well-established process, product, management and system capabilities”, MNE auto manufacturers began considering them as partners, involved them in joint design and development, and gave them preferred supplier status, even on a global scale. In addition, executives at several Tier 1 firms offered instances in which their firms were able to leverage their erstwhile Tier 1 status with one auto manufacturer to “get our foot in the door” at other MNE and domestic auto manufacturers.

Our results are also consistent with those obtained by other studies of the auto industry. For instance, McDermott and Corredoira (2010) found that relational networks were critical to technology upgrading in the Argentine auto components industry. In addition, detailed firm-level studies on the Indian auto industry have confirmed that technical collaborations have not only helped domestic firms to upgrade their technological capabilities, but have also improved their productivity and operational efficiency significantly (D’Costa, 2004; Ivarsson & Alvstam, 2005). Thereafter, MNE auto manufacturers began sourcing components such as sheet metal and fabricated parts, castings, forgings, some plastic and electrical components, fasteners and radiator caps from domestic firms with proven competencies, while continuing to source safety-critical and/or proprietary components for engines, transmissions, braking systems, electronics and certain instrument clusters from their global supply chain partners and transnational suppliers (Humphrey, 2003; Ivarsson & Alvstam, 2005). In addition, given the increasing tendency to maintain close relationships with only a few suppliers (Goffin et al., 2006; Mudambi & Helper, 1998), domestic firms with strong Tier 1 customer relationships probably enjoyed assured long-term demand.

Our other measure of domestic firms’ relationships with their customers (especially MNE auto manufacturers), FinCollab – that is, financial collaboration through minority investments – did not have a significant effect on domestic firms’ performance. One possibility for this result is that MNEs and their global supply chain partners made pre-emptive minority investments in domestic components firms, treating these as options for the future, but followed through selectively with efforts to help or exert control only if domestic firms’ efforts at catching up were successful. Furthermore, with global auto components firms setting up operations in India during the 1998–2002 phase, many of these options were probably allowed to “expire”. Indeed, the sheer number of financial collaborations after liberalization, with their numbers increasing during the 1998–2002 phase (see note 1), point to such a strategy on the part of MNEs.

However, the interaction effect between TechLicensing and FinCollab on domestic firms’ performance was negative and marginally significant (p<0.10). As our interviews suggested, MNEs tended to exert close control over domestic firms with which they had entered into both technological collaborations (through licensing agreements) and financial collaborations (through minority investments or joint ventures). These domestic firms would probably have faced the same stringent technological, productivity and pricing pressures as subsidiaries or MNE sources, exacting a toll on their performance. However, in return, these domestic firms had relatively assured demand for their products from their “patrons”, compared with their rivals. Therefore this result may be interpreted as a risk–return trade-off.

A second interpretation arises from our interviews with industry executives. With financial collaborations, any designs and intellectual property developed within the joint venture flowed back to the MNE partner, compromising the ability of the domestic partner to get the full performance benefits. Indeed, in one instance, an executive felt that his firm would have been better served by a simple technology licensing agreement instead of a joint venture with an MNE partner. This executive also indicated that the wholly Indian-owned components firms were likely to exhibit better financial performance than joint ventures.

Models 2a and 2b also revealed shifts in several relationships between the transition and consolidation phases. Firm size (Size) ceased to be critical for performance during the consolidation phase as MNE entrants gained familiarity with the Indian market and began relying on more pertinent criteria to drive their interactions with domestic suppliers. Instead, firm market share (Marketshare) became a significant and positive determinant of performance, indicating potential reputation effects. Unlike in the transition phase, Location was negatively associated with domestic firms’ performance during the consolidation phase. This negative effect of location may occur because the more capable domestic firms began serving several auto manufacturers simultaneously (as we uncovered in our interviews with industry executives). These firms had to locate units close to key auto manufacturers in multiple clusters (or at least maintain multiple warehouses with finished goods inventories), and also had to forge technology/financial collaborations with each of them. This need to establish multiple units probably constrained the potential for scale economies and learning/spillovers among the units, in turn resulting in lower performance (i.e., ROA).

In addition, the greater was the complexity of products offered by domestic firms (i.e., ProdComplexity), the lower was their performance during the consolidation phase. Our interviews suggested that domestic firms that had graduated to supplying relatively complex products were subjected to closer oversight on costs, pricing and quality, especially by MNE auto manufacturers. These firms also faced higher warranty costs, and had to continually upgrade their competencies to keep pace with the slew of new models introduced in the competitive but relatively low-volume Indian auto market (see Helper & Kiehl, 2004, who report the increasing oversight and new demands imposed by auto manufacturers on their suppliers).

During this phase, GDP growth exerted a significant negative influence on domestic firms’ performance. Indeed, with GDP growth and the resultant growth of the Indian auto market, new entry and larger-scale operations by MNEs increased competitive pressures on domestic firms, thereby negatively influencing their performance. However, the increasing market share of MNE auto manufacturers (MNEshare) was beneficial to domestic components firms’ performance, especially as MNE entrants increased domestic volume and indigenized aggressively by developing local sources, at least for standard components.

In sum, Models 1, 2a and 2b offer support for our Hypotheses 1 and 2.Footnote 10

Internal R&D and Performance

Internal R&D was not associated with domestic firms’ performance significantly, either in Model 1 or in Models 2a and 2b. This evidence may be interpreted as being partly consistent with Hypothesis 3. In other words, knowledge creation through internal R&D would be the final step in catch-up by domestic firms, and therefore will not materially affect performance during the transition and consolidation phases. Our results complement findings from the Indian auto industry during the 1980s that MNE entrants (primarily Japanese) were reluctant to lose steady revenues from licensing royalties, and discouraged domestic partner firms from investing in in-house R&D (Swaminathan, 1988).