Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Successful colorectal cancer screening relies in part on physicians ordering a complete diagnostic evaluation of the colon (CDE) with colonoscopy or barium enema plus sigmoidoscopy after a positive screening fecal occult blood test (FOBT).

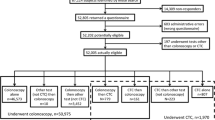

DESIGN: We surveyed primary care physicians about colorectal cancer screening practices, beliefs, and intentions. At least 1 physician responded in 318 of 413 (77%) primary care practices that were affiliated with a managed care organization offering a mailed FOBT program for patients aged ≥50 years. Of these 318 practices, 212 (67%) had 602 FOBT+ patients from August through November 1998. We studied 184 (87%) of these 212 practices with 490 FOBT+ patients after excluding those judged ineligible for a CDE or without demographic data. Three months after notification of the FOBT+ result, physicians were asked on audit forms if they had ordered CDEs for study patients. Patient- and physician-predictors of ordering CDEs were identified using logistic regression.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: A CDE was ordered for only 69.5% of 490 FOBT+ patients. After adjustment, women were less likely to have had CDE initiated than men (adjusted odds, 0.66; confidence interval, 0.44 to 0.97). Physician survey responses indicating intermediate or high intention to evaluate a FOBT+ patient with a CDE were associated with nearly 2-fold greater adjusted odds of actually initiating a CDE in this circumstance versus physicians with a low intention.

CONCLUSIONS: Primary care physicians often fail to order CDE for FOBT+ patients. A CDE was less likely to be ordered for women and was influenced by physician’s beliefs about CDEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

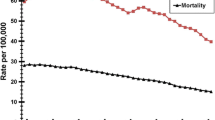

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER Compressed Mortality Database 1999. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.shtml. Accessed April 23, 2003.

Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472–7.

Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomized study of screening for colorectal cancer with fecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348:1467–71.

Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365–71.

Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, et al. The effect of fecal occult blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1603–7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State- and sex-specific prevalence of selected characteristics—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1996 and 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:1–39.

Sharma VK, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance practices by primary care physicians: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1551–6.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services: Report of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1996:89–103.

Byers T, Levin B, Rothenberger D, Dodd GD, Smith RA. American Cancer Society guidelines for screening and surveillance for early detection of colorectal polyps and cancer: update 1997. American Cancer Society Detection and Treatment Advisory Group on Colorectal Cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47:154–60.

Myers RE, Hyslop T, Gerrity M, et al. Physician intention to recommend complete diagnostic evaluation in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevent. 1999;8:587–93.

Azjen I, Fishbein M. Understanding, Attitudes, and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980.

Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Myers RE, Fishbein G, Hyslop T, et al. Measuring complete diagnostic evaluation in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Detect Prev. 2001;25:174–82.

Shields HM, Weiner MS, Henry DR, et al. Factors that influence the decision to do an adequate evaluation of a patient with a positive stool for occult blood. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:196–203.

Lieberman D. Screening/early detection model for colorectal cancer. Why screen? Cancer. 1994;74:2023–7.

Mandelblatt J, Andrews H, Kao R, Wallace R, Kerner J. The late-stage diagnosis of colorectal cancer: demographic and socioeconomic factors. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1794–7.

Donovan JM, Syngal S. Colorectal cancer in women: an under-appreciated but preventable risk. J Womens Health. 1998;7:45–8.

Erblich J, Bovbjerg DH, Norman C, Valdimarsdottir HB, Montgomery GH. It won’t happen to me: lower perception of heart disease risk among women with family histories of breast cancer. Prev Med. 2000;31:714–21.

Mandelson MT, Curry SJ, Anderson LA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening participation by older women. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:149–54.

Richards C, Klabunde C, O’Malley M. Physicians’ recommendations for colon cancer screening in women. Too much of a good thing? Am J Prev Med. 1998;15:246–9.

Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:618–26.

Daly SC, Roger VL, Leibson C, et al. Cardiology services after stress testing: are there sex differences? A population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:661–8.

Turner BJ, Markson LE, McKee LJ, Houchens R, Fanning T. Health care delivery, zidovudine use, and survival of women and men with AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1250–62.

Mocroft A, Gill MJ, Davidson W, Phillips AN. Are there gender differences in starting protease inhibitors, HAART, and disease progression despite equal access to care? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:475–82.

Arfken CL, Borisova N, Klein C, di Menza S, Schuster CR. Women are less likely to be admitted to substance abuse treatment within 30 days of assessment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34:33–8.

Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, Berg AO, Lohr KN. Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:132–41.

Nikolajevic-Sarunac J, Henry DA, O’Connell DL, Robertson J. Effects of information framing on the intentions of family physicians to prescribe long-term hormone replacement therapy. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:591–8.

Borum ML. Cancer screening in women by internal medicine resident physicians. South Med J. 1997;90:1101–5.

Massari V, Retel O, Flahault A. How do general practitioners approach hepatitis C virus screening in France? Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:119–24.

Fender GR, Prentice A, Gorst T, et al. Randomised controlled trial of educational package on management of menorrhagia in primary care: the Anglia menorrhagia education study. BMJ. 1999;318:1246–50.

Block B, Branham RA. Efforts to improve the follow-up of patients with abnormal Papanicolaou test results. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:77–9.

McCarthy BD, Yood MU, Janz NK, Boohaker EA, Ward RE, Johnson CC. Evaluation of factors potentially associated with inadequate follow-up of mammographic abnormalities. Cancer. 1996;77:2070–6.

Thomson-O’Brien MA, Oxman AD, Davis DA, Haynes RB, Freemantle N, Harvey EL. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000409.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, B., Myers, R.E., Hyslop, T. et al. Physician and patient factors associated with ordering a colon evaluation after a positive fecal occult blood test. J GEN INTERN MED 18, 357–363 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20525.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20525.x