Abstract

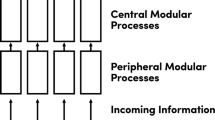

Evolutionary Psychology is based on the idea that the mind is a set of special purpose thinking devices or modules whose domain-specific structure is an adaptation to ancestral environments. The modular view of the mind is an uncontroversial description of the periphery of the mind, the input-output sensorimotor and affective subsystems. The novelty of EP is the claim that higher order cognitive processes also exhibit a modular structure. Autism is a primary case study here, interpreted as a developmental failure of a module devoted to social intelligence or Theory of Mind. In this article I reappraise the arguments for innate modularity of TOM and argue that they fail. TOM ability is a consequence of domain general development scaffolded by early, innately specified, sensorimotor abilities. The alleged Modularity of TOM results from interpreting the outcome of developmental failures characteristic of autism at too high a level of cognitive abstraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adolphs R., Tranel D., Damasio H. and Damasio A. 1994. Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature 372: 372-669.

Adolphs R., Tranel D. and Damasio A. 1998. The human amygdala in social judgement. Nature 393: 470-474.

Baron-Cohen S., Leslie A.M. and Frith U. 1985. Does the Autistic Child have a Theory of Mind? Cognition 21: 37-46.

Baron-Cohen S., Tager-Flusberg H. and Cohen D.J. (eds) 2000. Understanding Other Minds: Perspectives from Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Baron-Cohen S. and Ring H. 1994. A model of the mindreading system. Neuropsychological and neurobiological perspectives. In: Mitchell P. and Lewis C. (eds), Origins of an understanding of mind. Hillsdale, Erlbaum, NJ.

Baron-Cohen S., Ring H., Wheelwright S., Bullmore E., Brammer M., Simons A. et al. 2000. Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: and MRI study. European Journal of Neuroscience 11: 1891-1898.

Baron-Cohen S. 1995. Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and the Theory of Mind. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp xi-xviii.

Bloom P. and German T. 2000. Two reasons to abandon the false belief task as a theory of mind. Cognition 77: B25-B31.

Brown R., Hobson R.P. and Lee A. 1997. Are There ''Autistic-like'' Features in Congenitally Blind Children? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 38: 693-703.

Carruthers P. and Smith P.K. (eds) 1996. Theories of Theories of Mind. Cambridge University press, New York.

Coltheart M. 2000. Assumptions and Methods in Neuropsychology. In: Wixted J. (ed.), Stevens9 Handbook of Experimental Psychology. Methodology Vol. 4. 3rd edn..

Cosmides L. and Tooby J. 1992. Cognitive Adaptations for Social Exchange. In: Dupre J. (ed.), The latest on the Best. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Cosmides L. and Tooby J. 1994. Origins of Domain Specificity. In: Hirschfeld L. and Gelman Susan (eds), Domain Specificity in Cognition and Culture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Cosmides L. and Tooby J. 1997. The Modular Nature of Human intelligence. In: Scheibel A. and Schopf J. (eds), The Origin and Evolution of Intelligence. Jones and Bartlett publishers, Sudbury, MA, pp. 71-101.

Decety J., Perani D., Jeannerod M., Bettinardi V., Tadary B., Woods B. et al. 1994. Mapping Motor representations with PET. Nature 371: 600-602.

Frank 1988. Passions within reason: The strategic role of the emotions. Norton, New York.

Fodor J. 1983. The Modularity of Mind. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Fodor J. 1987. Frames Fridgeons Sleeping Dogs and the Music of the Spheres. In: Pylyshyn Z. and Norwood N.J. (eds), The Robot's Dilemma: The Frame Problem in Artificial Intelligence. Ablex.

Gallese V., Fadiga L., Fogassi G. and Rizzolati 1998. Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain 119: 593-609.

Gerrans P. 1998. The Norms of Cognitive Development. Mind and Language 13: 56-75.

Gerrans P. Rethinking Modularity. Journal of Language and Communication (forthcoming).

Gopnik A. 1993. Mindblindness. University of California, Berkeley, CA. (unpublished).

Griffiths P. and Gray R. 1994. Developmental Systems and Evolutionary Explanation. Journal of Philosophy 91: 277-304.

Happe F.G. 1994b. An Advanced Test of Theory of Mind: Understanding of Story Characters9 Thoughts and Feelings by Able Autistic, Mentally Handicapped and Normal Children and Adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 24: 129-154.

Heberlein A.S., Adolphs R., Tranel D., Kemmerer D., Anderson S. and Damaso A.R. 1998. Impaired attribution of social meanings to abstract dynamic visual patterns following damage to the amygdala. Society of Neuroscience Abstracts 24: 1176.

Heider F. and Simmel M. 1944. An experimental study of apparent behaviour. American Journal of Psychology 57: 243-259.

Heyes C.M. 1995. Knowing minds. Review of S Baron-Cohen 'Mindblindness', and D Byrne 'The Thinking Ape'. Nature 375: 290-290.

Heyes C.M. 1998. Theory of mind in nonhuman primates. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 21: 101-148.

Heyes C.M. Theory of mind and other domain-specific hypotheses. Author's Response to Continuing Commentary. Behavioral and Brain Sciences (in press).

Hobson R.P. 1991. Through Feeling and Sight to Self and Symbol. In: Neisser U. (ed.), Ecological and Interpersonal Knowledge of the Self. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Hobson R.P. 1992. Social Perception in High-Level Autism. In: Schopler E. and Mesibov G. (eds), High-Functioning Individuals with Autism. Plenum Press, New York.

Hobson R.P. 1993a. Autism and the Development of Mind. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd., East Sussex, UK.

Hobson R.P. 1993b. Understanding Persons: The Role of Affect. In: Baron-Cohen S., Tager-Flusberg H. and Cohen D.J. (eds), Understanding Other Minds: Perspectives from Autism. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 204-227.

Karmiloff-Smith A. 1998. Development itself is the key to understanding mental disorders. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2: 389-399.

Leslie A.M. 1987. Pretense and Representation. The Origins of a ''Theory of Mind''. Psychological Review 1987 94: 412-426.

Leslie A. and Thaiss L. 1992. Domain specificity in conceptual development: evidence from autism. Cognition 43: 225-251.

Leslie A.M. 1994. ToMM, ToBY and Agency: Core Architecture and Domain Specificity. In: Hirschfield L. and Carey S. (eds), Mapping the Mind: Domain Specificity in Cognition and Culture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Lewontin R. 1978. Adaptation. Scientific American 239: 156-169.

Mc Geer V. 2001. Psycho-Practice, Psycho-Theory, and the Contrastive Case of Autism: How Practices of Mind Become Second Nature. Journal of Consciousness studies.

Oyama S. 1985. The Ontogeny of Information. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Page T. 2000. Metabolic approaches to the treatment of autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autistic Developmental Disorders 30: 463-469.

Peterson C.C., Peterson J.C. and Webb J. 2000. Factors Influencing the Development of a Theory of Mind in Blind Children. The British Psychological Society 18.

Peterson C.C. and Siegal M. 1998. Changing Focus on the Representational Mind: Concepts of False Photos, False Drawings and False Beliefs in Deaf, Autistic and Normal Children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 16: 301-320.

Peterson C.C. and Siegal M. 1999. Insights into Theory of Mind from Deafness and Autism. Mind and Language 15: 77-99.

Pinker S. 1994. The Language Instinct. William Morrow & Co., New York.

Pinker S. 1997. How the Mind Works. Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Plotkin H. 1997. Evolution in Mind. London Allen Lane.

Povinelli D. 1996. What young chimpanzees know about seeing. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill.

Rutter M. and Schopler E. 1987. Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders: Conceptual and Diagnostic Issues. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 17: 159-186.

Samuels R. 1998. Evolutionary Psychology and the Massive Modularity Hypothesis. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 49: 575-602.

Sperber D. 1994. Explaining Culture. Oxford Blackwell.

Sperber D. and Wilson D. 1996. Fodor's Frame Problem and Relevance Theory (reply to Chiappe & Kukla). In: (ed.), In Behavioral and Brain Sciences 19., pp. 530-532.

Stern D. 1985. The Interpersonal World of the Infant. Basic Books, New York.

Sterelny K. 1995. The Adapted Mind. Biology and Philosophy 10: 365-380.

Stone V.E., Baron-Cohen S. and Knight R.T. 1998. Frontal Lobe contributions to theory of mind. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 10: 640-656.

Suddendorf T. and Whiten A. Mental evolution and development: evidence for secondary representation inchildren, great apes and other animals. Psychological Bulletin (in press).

Suddendorf T. 1998. Simpler for evolution: Secondary representation in apes, children, and ancestors. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 21: 131-131.

Tooby J. and Cosmides L. 1992. The Psychological Foundations of Culture. In: Barkow J., Cosmides L. and Tooby J. (eds), The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Tooby J. and Cosmides L. 1995. Forward. In: (ed.), Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and the Theory of Mind. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA pp xi-xviii.

Trevarthen C. 1979. Communication and Cooperation in Early Infancy: A Description of Primary Intersubjectivity. In: Bullowa M. (ed.), Before Speech: The Beginning of Interpersonal Communication. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Trevarthen C. and Hubley P. 1978. Secondary Intersubjectivity: Confidence, Confiding and Acts of Meaning in the First Year. In: Lock A. (ed.), Action, Gesture and Symbol: The Emergence of Language. Academic Press, London.

Zaitchik D. 1990. When Representations Conflict with Reality: The Preschooler's Problem with False Belief and 'False' Photographs. Cognition 35: 41-68.

Whiten A. and Byrne (eds) 1997. Machiavellian Intelligence. Extensions and Evaluations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Wimmer H. and Perner J. 1983. Beliefs about Beliefs: Representation and the Constraining Function of Wrong Beliefs in Young Children's Understanding of Deception. Cognition 13: 103-128.

Wing L. and Gould J. 1978. Systematic Recording of Behaviours and Skills of Retarded and Psychotic Children. Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia 8: 79-97.

Wing L. and Gould J. 1979. Severe impairments of social interactions and associated abnormalities in children: Epidemiology and classification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 9: 11-29.

Winner E., Brownell H., Happe F., Blum A. and Pincus D. 1988. Distinguishing lies from jokes-theory of mind deficits and discourse interpretation in right hemisphere brain damaged patients. Brain & Language 62: 89-106.

Zaitchek D. 1990. When representations conflict with reality: the preschooler's problem with false belief and “false” photographs. Cognition 35: 45-57.

Waterhouse L., Fein D. and Modahl C. 1996. Neurofunctional mechanisms in autism. Psychological Review 103: 457-489.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gerrans, P. The theory of mind module in evolutionary psychology. Biology & Philosophy 17, 305–321 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020183525825

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020183525825