Abstract

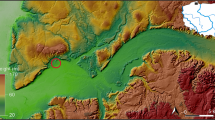

The external connections of Igbo-Ukwu, in the forest belt of south-eastern Nigeria, around the ninth century AD, are demonstrated by the large numbers of glass beads, apparently of Egyptian manufacture, and are implicit in the rich collection of bronze artwork that lacks known prototypes. Although the metals were mined locally, the labor and the expert alloying and casting of numerous ritual or ornamental objects indicate an accumulation of wealth derived from distant trade of special commodities. The identification of these commodities, however, and the routes by which they—and in the reverse direction the beads—would have traveled, remain unsatisfactorily resolved. A preference is repeated here for an eastern Sahelian routing from Lake Chad to the Middle Nile kingdoms (Alwa and Makuria/Dongola), then at their height, thus avoiding the Sahara. The alternative direction suggested recently (Insoll, T., and Shaw, T. (1997) Gao and Igbo-Ukwu: Beads, interregional trade and beyond. African Archaeological Review, 14:9–23), through Gao on the Niger bend and across the west-central Sahara, seems less likely on grounds of geography and chronology. The essential items of merchandise deriving from Igbo-Ukwu are unlikely to be those commonly assumed for sub-Saharan Africa, notably ivory and slaves, but would have been more local and precious, presumably metals. The bronzes stored and buried at Igbo-Ukwu might be regarded as by-products of this export activity. Demands in the Nile Valley for tin (for bronze alloying) and for silver, both of which occur in the ores exploited, deserve consideration. A call is made for comparative study of metals and their uses between the Middle Nile and West Africa in the first millennium AD—a neglected subject owing to the intellectual gulf that persists between Africanists and Egyptologists.

Les contacts extérieurs d'Igbo-Ukwu, dans la région forestière du sud-est du Nigéria, vers le 9e siècle après J. C., sont indiqués par les très nombreuses perles de verre, apparemment de fabrication Égyptienne. Ils sont aussi suggérés par un ensemble remarquable d'objects en bronze dont on ne connaît aucun prototype. Bien que les métaux proviennent de la région, le travail, et aussi l'alliage et la fonte très spécialisés de nombreux objects rituels ou décoratifs, indiquent une accumulation de richesse résultant du commerce à longues distances de produits recherchés. Pourtant, l'identification de ceux-ci, et les itinéraires pour leur transport—et, en sens inverse, ceux des perles—restent hypothétique. Nous réiterons une préférence pour une route est-Sahelien, de Lac Tchad jusqu'aux royaumes du Nil Moyen (Alwa et Makouria/Dongola), à leur apogée à cette époque, et donc évitant le Sahara. L'autre direction, proposée récemment (dans cette revue par Insoll et Shaw), via Gao sur la boucle du Niger et à travers le Sahara ouest-central, semble moins probable pour les raisons géographiques et chronologiques. Les objets principaux de ce commerce qui provenaient d'Igbo-Ukwu ne seraient pas ceux qui sont normalement imaginés pour l'Afrique Sub-saharienne, notamment l'ivoire et les esclaves; ce seraient des produits plus locaux et précieux, vraisemblablement des métaux. Les bronzes enterrés à Igbo-Ukwu pourraient être les sous-produits de cette activité destinée à l'exportation. La demande dans la vallée du Nil pour l'étain (pour l'alliage du bronze) et pour l'argent, qui existent tous les deux dans les minerais du sud-est du Nigéria, mérite considération. Il faut qu'on fasse des recherches comparatives sur les métaux et leurs emplois entre le Nil Moyen et l'Afrique de l'Ouest durant le premier millénaire après J. C.—un sujet négligé à cause du fossé intellectuel qui persiste entre les études Africanistes et Égyptologiques.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES CITED

Adams, W. Y. (1977). Nubia: Corridor to Africa, Allen Lane, London.

Bivar, A. D. H., and Shinnie, P. L. (1962). Old Kanuri capitals. Journal of African History 3: 1–10.

Blench, R. M. (1993). Ethnographic and linguistic evidence for the prehistory of African ruminant livestock, horses and ponies. In Shaw, T., Sinclair, P., Andah, B., and Okpoko, A. (eds.), The Prehistory of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns, Routledge, London, pp. 71–103.

Bourges, C., MacEachern, S., and Reeves, M. (1999). Excavations around Aissa Hardé, 1995 and 1996. Nyame Akuma 51: 6–13.

Chikwendu, V. E., Craddock, P. T., Farquhar, R. M., Shaw, T., and Umeji, A. C. (1989). Nigerian sources of copper, lead and tin for the Igbo-Ukwu bronzes. Archaeometry 31: 27–36.

Chikwendu, V. E., and Umeji, A. C. (1979). Local sources of rawmaterials for the Nigerian bronze/brass industry: With emphasis on Igbo-Ukwu. West African Journal of Archaeology 9: 151–165.

Cowell, M. (1995). Preliminary report on the examination of the metalwork from the temples of Kawa, Sudan. Sudan Archaeological Research Society Newsletter 8: 34–38.

Craddock, P. T. (1985). Medieval copper alloy production and West African bronze analyses-Part I. Archaeometry 27: 17–41.

Craddock, P. T., Ambers, J., Hook, D. R., Farquhar, R. M., Chikwendu, V. E., Umeji, A. C., and Shaw, T. (1997). Metal sources and the bronzes from Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria. Journal of Field Archaeology 24: 405–429.

Diop, C. A. (1960). L'Afrique Noire Pré-Coloniale, Présence Africaine, Paris.

Dunham, D. (1963). The Royal Cemeteries of Kush: Vol. V. The West and South Cemeteries at Meroë, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Edwards, D. (1996). The Archaeology of the Meroitic State, African Archaeology Monograph 38, British Archaeological Reports, Oxford.

Emery,W. B., and Kirwan, L. P. (1938). The Royal Tombs of Ballana and Qustul, Service des Antiquités de l' Égypte (Mission archéologique de Nubie, 1924-34), Cairo.

Fairman, H. W. (1965). Ancient Egypt and Africa African Affairs (Special issue), 69–75.

Griffith, F. L. (1924-26). Oxford Excavations in Nubia, XXXIII: The Meroitic Cemetery at Faras. Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology XI: 141–180.

Griffith, F. L. (1926-28). Oxford Excavations in Nubia, XLVII: The Church by the Rivergate. Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology XIII, XV.

Insoll, T. (1996). Islam, Archeology and History: Gao Region (Mali) ca. AD 900-1250, Tempvs Reparatvm, Oxford.

Insoll, T., and Shaw, T. (1997). Gao and Igbo-Ukwu: Beads, interregional trade, and beyond. African Archaeological Review 14: 9–23.

Kirwan, L. P. (1939). The Oxford University Excavations at Firka, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Lebeuf, J.-P. (1962). Archéologie tchadienne: les Sao du Cameroun et du Tchad, Hermann for CNRS, Paris.

Michalowski, K. (1966) Faras: centre artistique de la Nubie chrétienne, Nederlands Institut voor het Nabije Oosten, Leiden.

Oliver, R., and Fage, J. D. (1962). A Short History of Africa, Penguin, Harmondsworth.

Roy, B., and Insoll, T. (1998). The beads from the 1996 excavation season in Gao. Bead Study Trust Newsletter 32: 4–7.

Rubin, A. (1973). Bronzes of the middle Benue. West African Journal of Archaeology 3: 221–231

Rubin, A. (1974). Notes on regalia in Biu Division. West African Journal of Archaeology 4: 161–175.

Seligman, C. G. (1934). Egypt and Negro Africa, Frazer Lecture for 1933, University of Liverpool.

Shaw, T. (1970). Igbo-Ukwu: An Account of Archaeological Discoveries in Eastern Nigeria, Faber, London.

Shaw, T. (1975). Those Igbo-Ukwu radiocarbon dates. Journal of African History 16: 603–617.

Shaw, T. (1977). Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu: Archaeological Discoveries in Eastern Nigeria, Oxford University Press, Ibadan.

Shaw, T. (1995). Further light on Igbo-Ukwu, including new radiocarbon dates. In Andah, B. W., de Maret, P., and Soper, R. (eds.), Proceedings of the 9th Congress of the Panafrican Association of Prehistory, Ibadan, 1983, Rex Charles, Ibadan, pp. 79–83.

Shinnie, P. L. (1961). Excavations at Soba, Sudan Antiquities Service, Occasional Paper 3, Khartoum.

Shinnie, P. L. (1967). Meroe: A Civilization of the Sudan, Thames and Hudson, London.

Shinnie, P. L. (1971). The culture of medieval Nubia and its impact on Africa. In Yusuf Fadl Hasan (ed.), Sudan in Africa, Khartoum University Press, Khartoum, pp. 42–50.

Shinnie, P. L., and Bradley, R. J. (1980). The Capital of Kush 1: Meroe excavations 1965–1972, Akademie Verlag, Meroitica 4, Berlin.

Shinnie, P. L., and Shinnie, M. (1978). Debeira West: A Mediaeval Nubian Town, Aris & Phillips, Warminster.

Sutton, J. E. G. (1983). West African metals and the ancient Mediterranean. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 2: 181–188.

Sutton, J. E. G. (1985). The antiquity of horses and asses in West Africa: A correction. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 4: 117–118.

Sutton, J. E. G. (1991). The international factor at Igbo-Ukwu. African Archaeological Review 9: 145–160.

Sutton, J. E. G. (1997). The African lords of the intercontinental gold trade before the Black Death: al-Hasan bin Sulaiman of Kilwa and Mansa Musa of Mali. Antiquaries Journal 77: 221–242.

Talbot, P. A. (1926). Peoples of Southern Nigeria, I, Oxford University Press, London.

Vansina, J. (1984). Art History in Africa, Longman, London and New York.

Welsby, D. A. (1998). Soba II: Renewed excavations within the metropolis of the kingdom of Alwa in Central Sudan, Memoir 15, British Institute in Eastern Africa, British Museum Press, London.

Welsby, D. A., and Daniels, C. M. (1991). Soba: Archaeological Research at a Medieval Capital on the Blue Nile, Memoir 12, British Institute in Eastern Africa, London.

Williams, B. B. (1991). Meroitic Remains from Qustul and Ballana, Oriental Institute Nubian Expedition, Vol. VIII, Oriental Institute, Chicago.

Woolley, C. L., and Randall-MacIver, D. (1910). Karanog: The Romano-Nubian Cemetery, Coxe Expedition to Nubia, Vols. III /IV, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sutton, J.E.G. Igbo-Ukwu and the Nile. African Archaeological Review 18, 49–62 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006792806737

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006792806737