Abstract

Background

Strategic hedging is a form of behavior used by states wanting to improve their competitiveness while at the same time avoiding direct confrontation with main contenders. It is an appealing option for states facing uncertainty due to structural changes in the international system such as the present unipolarity giving way to a process of power diffusion. Under such conditions, strategic hedging becomes an attractive alternative for other strategies like balancing, bandwagoning, and buckpassing. Especially for second-tier states, it becomes a behavior of choice vis-à-vis the system leader.

Aims

The strategic hedging research program, however, is in its early stages. Previous research on strategic hedging developed without a clear account of national hedging capabilities, making it difficult to understand key reasons for successful hedging in some cases and its failure in others. This study represents the first attempt to measure the core components of a state’s strategic hedging capability and as such provides a comparative snapshot of those components by means of a composite index.

Methods

The index comprises three core dimensions (economic capability, military power and decision-making capability), which are broken down into six sub-indicators: gross domestic product (GDP), foreign exchange and gold reserves, government debt, military expenditure, growth of military arsenal, and democracy. Because second-tier states in the international system are likely to have the greatest incentives to engage in strategic hedging, the composite index developed in this study is applied to a sample of seven leading second-tier states in a comparative case study.

Results

The results indicate that for states to score high on strategic hedging capability, they need to score high on all core dimensions. Negligence of one of the components leads to a significant decline in total hedging capacity. Such results show why China tops the strategic hedging capability index and scores significantly higher than the other second-tier states.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

According to Nye (1990, 2004), a nation’s power comprises both hard power and soft power. In recent years scholars have tried to better understand the relationship between hard power and soft power. For instance, in his study about China’s policy in the Middle East, Alterman (2009: 75) stated: “Chinese power in the region is destined to become more balanced between hard and soft power over time”. In 2011, a more articulated effort was undertaken applying the concept of strategic hedging to China’s energy security strategy (Tessman and Wolfe 2011). In this study strategic hedging (by China) was interpreted as a type of second-tier states’ behavior against the system leader in a unipolar system, where the hedging state attempts to improve its competitive ability (military and economic) while avoiding direct confrontation with the system leader. What makes the strategic hedging approach particularly interesting is that it addresses a wider range of strategies than hard balancing and also has a much stronger connection to system structure than the soft balancing concept (Tessman and Wolfe 2011; Tessman 2012; Wolfe 2013).

The strategic hedging research program is in its early stages and in need of progressive development. Previous research on strategic hedging has evolved without a clear account of national hedging capabilities, making it difficult to understand the key reasons for successful hedging in some cases and its failure in others. This article discerns the core components that contribute to a state’s strategic hedging capability and develops a composite index that provides a comparative snapshot of those components. The potential of this composite index is illustrated by a comparative case study of the leading seven second-tier states, namely China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Russia, and UK.Footnote 1

In the following, we first review the meaning of strategic hedging in International Relations and articulate it specifically with regard to second-tier states. Secondly, we present three dimensions together with six sub-indicators that capture a state’s strategic hedging capability. In the third section, we present the specification of the model and datasets after which we examine the leading seven second-tier states as comparative case study for the year 2013. In the last section, we analyze the results, offer some conclusions, and outline ways to improve the measurement of strategic hedging in the future.

2 What is Strategic Hedging?

Since the end of the Cold War, several second-tier states have attempted to transform the international system from unipolarity to multipolarity (Layne 1993: 9–10; Monteiro 2011: 10). These included efforts to improve competitiveness while avoiding direct confrontation with the system leader. For example, the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) evolved from a mere concept into a more formal political grouping to maximize leverage, and to avoid negative attention by hiding in a group (Glosny 2010: 100). In response to this development, the soft balancing concept was introduced to capture uses of nonmilitary tools to delay, frustrate, confront, and undermine the system leader, for instance, using “international institutions, economic statecraft, and diplomatic arrangements” (Pape 2005: 10).

Recently, the concept of strategic hedging has been introduced in an effort to improve upon the concept of soft balancing. Strategic hedging is a form behavior used by states wanting to improve their competitiveness while at the same time avoiding direct confrontation with main contenders. It is an appealing option for states facing uncertainty due to structural changes in the international system such as the present unipolarity giving way to a process of power diffusion (Geeraerts 2011). Under such conditions, strategic hedging becomes an attractive alternative for other strategies like balancing, bandwagoning, and buckpassing (see, Tessman 2012: 192; Salman et al. 2015: 576–577). Especially for second-tier states, it becomes a behavior of choice vis-à-vis the system leader. Hedging helps second-tier states to face specific kinds of uncertainty and to improve their security position in case the relationship with the system leader would deteriorate (Tessman and Wolfe 2011: 236; Tessman 2012: 192; Salman and Geeraerts 2015; Salman et al. 2015). Strategic hedging aims to cover the ground between hard and soft power, where the hedging state seeks to improve its competitive capability (military and economic) while, at the same time, avoiding direct confrontation with the system leader. We operate under the assumption that there is a behavioral pattern, which indicates when strategic hedging is occurring in the international system and when it is not (Tessman and Wolfe 2011: 220; Tessman 2012: 193; Salman and Geeraerts 2015: 105–106). Second-tier states engage in strategic hedging when their behavior shows the following pattern: the hedging state (1) develops its economic capacity to deal with short-term domestic and international costs flowing from tensions with the system leader, including increasing strategic reserves affected by the system leader’s public good provision; (2) improves its military capability in anticipation of a possible confrontation with the system leader while, at the same time, avoiding outright provocation of the latterFootnote 2; (3) coordinates decisions to do so centrally at the highest levels of government since national security interests are at stake.

3 Indicators of Strategic Hedging Capability

For a state to engage in strategic hedging it needs the capability to do so. While there is no direct causal relation between capability and actual behavior, capabilities give an idea of possible behavior and as such loom large in any strategic calculation. As is the case with all power-related concepts strategic hedging capability is inherently difficult to quantify. To facilitate comparison, we create a composite index of strategic hedging determinants. Tessman and Wolfe (2011) have previously pointed to three primary factors that generate strategic hedging (economic capacity, military power, and central government). Other characteristics included are improvement of competitive ability of the hedging state, avoidance of direct confrontation with the system leader, willingness to accept costs and coordination at the highest levels of government (Tessman and Wolfe 2011: 220). Our index takes Tessman and Wolfe’s three primary factors as a starting point, but expands on them and introduces six sub-indicators: gross domestic product (GDP), foreign exchange and gold reserves, government debt, military expenditure, growth of military arsenal, and democracy. The first three indicators relate to economic capability, the next two to military power, and the last one to decision-making capability. Figure 1 illustrates the six factors that comprise our strategic hedging index.

3.1 Economic Capacity

An increase in relative economic power tends to improve a nation’s international political influence where this economic power could be harnessed for the purposes of foreign policy (Zakaria 1998). Cheng Gao has underlined that rising powers during the industrial age sought to accumulate wealth to use this wealth in the restructuring of the international system (Gao 2011). Harrison (1998: 1–2) has also noted that the economic superiority of the Allies in the Second World War gave them an overwhelming advantage on the battlefield, and helped to defeat the Axis powers. Given the importance of economic power in the implementation of strategic hedging, three economic indicators are used to measure the strategic hedging ability (gross domestic product, foreign exchange reserves, and government debt).

3.1.1 Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period of time (Mankiw and Taylor 2006: 468). In fact, there is a strong correlation between GDP levels and all important factors contributing to people’s welfare, such as improving nutrition, health care, telecommunications, and life expectancy (Schepelmann et al. 2010). Lieber and Alexander (2005) confirmed the importance of measuring internal balancing in proportion to GDP. Importantly, GDP is a significant indicator of military victory in great power warfare, and plays an important role in determining future relations between great powers (Zuljan 2003). Consequently, GDP is an important criterion for measuring strategic hedging capability; it supports the national economy, helps the provision of foreign aid, and increases the ability to bear additional costs resulting from hedging policies.

3.1.2 Foreign Exchange and Gold Reserves

Foreign exchange reserves are assets held by central banks and monetary authorities. They usually consist of gold and various global currencies such as US dollar, euro, pound sterling, and yen. Central banks attempt to preserve the liquidity of foreign exchange reserves to meet payments in foreign currency and to confront financial crises (Zhang et al. 2013: 138). Importantly, foreign exchange reserve plays a significant role in hedging overall macroeconomic risks (Li et al. 2012: 1524). High volume of foreign exchange reserve and gold makes the hedging state ready to accept domestic and international costs in the short-term as part of hedging behavior. Consequently, foreign exchange reserve is used as a positive indicator to measure strategic hedging capability.

3.1.3 Government Debt

Government debt is the debt owed by a central government. The process of establishing and implementing a strategy for prudently managing this debt is called ‘Government Debt Management’. The target of this process is to ensure meeting the government’s financing needs and the needs of government borrowing (Wheeler 2004: 4). Recently, government debt relative to GDP has risen in several great powers more than at any time since the Second World War. This ratio is projected to grow for years to come. Policymakers in these countries seek to increase tax revenues and to reduce public spending, which decrease the willing to accept additional costs (MCK 2013). In the meantime, increasing government debt ratio of GDP could undermine the implementation of hedging policies. Therefore, it has been used as a negative indicator.

3.2 Military Power

Military power has a dual and contradictory effect from the standpoint of hedging behavior. While strategic hedging involves upgrading of military capabilities, it seeks to avoid provoking the system leader either through increasing its military arsenal provocatively or through entering into an alliance against the latter (Tessman and Wolfe 2011; Tessman 2012; Salman and Geeraerts 2015). For these reasons, we chose two indicators, one positive and the other negative to measure the impact of military power on strategic hedging.

3.2.1 Military Expenditure

The financial management of the entire military sector is essential to protect the state and its population against internal and external threats. Military spending in the strategic hedging framework is somewhat similar to the arms race dynamic. Both of them occur in peacetime and involve a gradual increase in armaments resulting from conflicting purposes and/or mutual fears under conditions of uncertainty (Huntington 1958; Tessman and Wolfe 2011). Importantly, increases in the military expenditure lead to improvement of the competitive military ability of the hedging state. The size of military spending, therefore, is a positive indicator of the level of hedging.Footnote 3

3.2.2 Growth of Military Arsenal

While improving competitive military ability is essential to strategic hedging, the hedging state should avoid an extensive arms buildup that might disturb the system leader and lead to a dispute, a crisis, or a military confrontation (Tessman 2012; Salman et al. 2015). Moreover, there is a negative causal relationship between military spending and economic growth, especially when military expenditure leads to negative economic growth (Chang et al. 2011). In this context, military spending relative to GDP is used as a negative critical indicator for measuring strategic hedging capability.

3.3 Central Government

Implementation of sovereign decision is a basic pillar of hedging behavior. Rich nations do not routinely become great powers; they need a strong central government to harness the economic and military power for the purposes of foreign policy, which explains why the United States was a minor power in the late nineteenth century although it was the richest country in the world, including military, economic, political, and diplomatic factors (Zakaria 1998). Therefore, it is mandatory to allocate at least one indicator to measure central authority.

3.3.1 Democracy

Proportional representation (PR) electoral rules have a significant positive effect on economic growth as they lead to the expansion of government spending on education and health, property rights protection and free-trade (Knutsen 2011). Democracy also allows for a greater number of citizens to participate in the proposal and the introduction of laws, and is positively related to household income (Andersen 2012). Despite these benefits high levels of democracy lead to reduce a central authority’s capability to make decisions, and thus to a decline in coordination at the highest levels of government, which is one of the most important conditions for strategic hedging.Footnote 4 Within the framework of democratic peace theory, Michael Doyle has pointed out that liberal principles and institutions hinder and disrupt the pursuit of balance-of-power politics (Doyle 1983). Accordingly, democracy is used as a negative indicator in our index.

4 Model, Data and Analysis

4.1 Sources and Description of Data

All data have been taken for the year 2013. The leading seven second-tier states (China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Russia, and UK) have been selected on the basis of their being the largest economic and/or military powers in the world (except the United States as a system leader) and are used for a comparative case study. The study uses six different datasets that help to measure the components of strategic hedging (gross domestic product, reserve of foreign exchange, government debt of GDP, military expenditure, military expenditure of GDP, and democracy). Table 1 illustrates the sources of these data.

4.2 Model and Estimations

As said before, strategic hedging is inherently difficult to quantify. To facilitate the comparison process, we use min–max indicators that allow having an identical range [0, 1] by subtracting the minimum value and dividing by the range of the indicator values. For negative indicators, we use the same model, but work with absolute values. This method follows an OECD publication on constructing composite indexes (OECD 2008: 30):

4.3 Country Results

The results for the top seven second-tier states in 2013, ranked by score of strategic hedging, are presented in Table 2. China easily wins the strategic hedging race according to our index with a score of 5.61 points, which is about 3.33 points higher than Russia’s. Russia ranks second with 2.28 points; followed by India, Japan, and Germany with 2.02, 1.98, 1.82 points, respectively. France and the United Kingdom run as close sixth and seventh with 1.57 and 1.40 points, respectively.

4.4 Country Analyses

The following section summarizes the results for the top second-tier states that were ranked by the strategic hedging index for the year 2013.

4.4.1 China

The rise in China’s strategic hedging capabilities in recent years has been nothing short of spectacular; showing increasing defense budgets, significant economic growth, and a strong central government, while Beijing, at the same time, is avoiding direct collision with Washington (Wang 2005; Wolfe 2013; Salman and Geeraerts 2015; Salman et al. 2015). China has a distinctive character in its international behavior, exhibiting both elements of threat and peaceful intentions (Breslin 2013; Dreyer 2007; Schweller and Xiao 2011; Salman and Geeraerts 2015; Salman et al. 2015).

Since the adoption of market-oriented economic reforms after Mao’s death, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has enjoyed rapid economic growth. In recent years, it surpassed Germany and displaced Japan to become the world’s second largest economy in 2012. If current trends continue, China will become America’s international equal in the 2020s (Bandow 2012; Layne 2012; Schweller and Xiao 2011). To bolster its international standing, China increasingly supports multilateral diplomacy. It is willing to bear the extra cost in the short term to reach this objective. For example, to obtain a more active role in the global economy, China’s leaders have accepted several concessions to comply with the country’s WTO obligations (Aaronson 2010). China’s reserves of foreign currency have already exceeded its needs with a current account surplus and a capital account surplus for more than two decades, making China the largest creditor of the United States (Yongding 2011). China has used its economic prowess to support its position in the international community and to protect itself from Washington. Following the global financial crisis in 2008, China’s central bank suggested abandoning the US dollar as the international reserve currency, and the establishment of a new global system controlled by the International Monetary Fund (Anderlini 2009). Recently, China has proposed the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as an international financial institution that could be a rival for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) (see Branigan 2015).

On the other hand, China’s military budget has increased in recent years, amounting to approximately 10.1 % of the total military expenditure in the world (Fig. 2). Beijing is developing its military capabilities, and seeks to construct a ‘blue-water fleet’ that could change the balance of power in the Asia Pacific. For example, the Chinese submarine fleet includes at least three new strategic missile submarines ‘Type 094’, each built with 12 missile launch tubes, which could be equipped with new JL-2 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). China invests considerably in this area. Soon Beijing may add at least two new generation missile submarines ‘Type 096’ and it also plans to deploy an anti-satellite missile on these submarines. These new submarines would further enhance Chinese growing undersea fleet (Gertz 2013). Moreover, the Chinese military has tested emerging technology aimed at destroying missiles in mid-air, which could help to build a shield for air defense by intercepting incoming ballistic missiles in space (Xinhua 2013). Such attempts constitute a threat to the strategic interests of the United States. For instance, according to a RAND report, Washington will not be able to defend Taiwan from Chinese military attack by 2020 (Newmyer 2009).

Global distribution of military expenditure in 2013. Source SIPRI Military Expenditure Database (2014)

Finally, Chinese decision-making, also in the realm national security, is a centrally coordinated process that is heavily influenced by the expectations and beliefs of key decision makers in the Party, the state, and the Central Military Commission (Huiyun 2009). All in all, China has adopted a correct track for successful hedging: it focuses primarily on economic development, and in doing so tries to create a balance between economic and military capabilities while centrally coordinating its policies at the highest levels of government. Given these reasons, China constitutes a perfect example of a strategic hedging state, and tops the strategic hedging index with a score that is significantly higher than Russia, which occupies the second place (Fig. 3).

4.4.2 Russia

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, significant structural changes have affected the Russian economy such as the end of the dominance of state ownership of industry, a large-scale privatization campaign, and liberalization of prices—even the military sector was not immune to these changes (Cooper 2013). However, Russian economy still retains several features inherited from the central economic system of the Soviet Union, especially in the military sector, which aims to enhance the country’s military capability (Cooper 2013). The Russian army, as a nuclear power, is considered the second force in the world after the US military (Rywkin 2012). Moreover, the Russian government debt is very low compared with other great powers. Russian government, thereby, is more willing to implement the sovereign financial decisions. Finally, the decline of democracy has increased the sovereign decision-making capacity, especially during Putin’s term, who declared his goal as the ‘dictatorship of law’ to overcome the legal fragmentation in the federal system (Horvath 2011; Sakwa 2008). In that light, Russia occupies the second place in the strategic hedging index (Fig. 4).

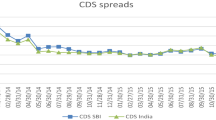

Conversely, Russia obtains a much smaller score than China in our index for several reasons: First, the ratio of military spending to GDP is high in Russia, which tends to provoke the United States (SIPRI 2014). Secondly, the Russian GDP is much smaller than other major countries’ such as China, Japan, and Germany (Fig. 5). Indeed, the significant economic growth capabilities could only be secured through high prices for oil and gas, making Russian economy susceptible to a rupture as a result of large fluctuations in the oil price (Benedictow et al. 2013; Rutland 2008). Arguably, Russia has exaggerated its emphasis on the military aspect without paying enough attention to economic capacity, which has created a kind of imbalance in its of strategic hedging capability.

4.4.3 India

India is rapidly emerging as a power in the world. According to the World Bank, the country’s national income has increased more than threefold over the last decade, while military spending doubled over the same period to become the largest arms importers in the world (SIPRI 2014). New Delhi seeks to take advantage of Washington’s support to ensure a power balance in Asia against China, especially in the military field. The Indian Navy has regularly participated in the ‘Exercises Malabar’ with the United States.Footnote 5 India also seeks to seal arms deals with Washington, like acquiring the maritime version of the F-35 ‘the Joint Strike Fighter’ (Evans 2011). Undoubtedly, India has not reached the level of other great powers militarily or economically yet, but obtains a relatively high rank in the strategic hedging index due to its geopolitical position, rising foreign exchange reserves, and the low level of public debt (Table 3).

4.4.4 Japan

For contradictory reasons, Japan comes in the middle of the index. Economically, Japan has a huge national income, a large amount of foreign currency reserves, a diversified economy between industry and agriculture, and a great export activity (Okabe 2013). On the other hand, the Japanese economy suffers from a high level of government debt. Tokyo occupies a high position in the ranking of the world’s debtors (see, Table 1). Recently, in an attempt to rein in public debt, the Japanese government sharply raised the consumption tax to increase government revenue, which led Japan’s economy to contract dramatically (Pandey 2014).

Militarily, Japan has followed ‘Yoshida Doctrine’Footnote 6 based on a pacifist constitution, which is functional in avoiding provocation of the system leader. As a consequence, the ratio of military spending to GDP in Japan is very low. Importantly, Japan’s military spending did not increase significantly during the last decade, unlike the other major nations’ such as China, Russia and India (Fig. 6).

Military expenditure by Countries, 2000–2013 (Million US$). Source SIPRI Military Expenditure Database (2014)

However, the defense white paperFootnote 7 shows that Japanese Army is one of the best well-equipped ‘invisible’ armies in the world. Tokyo could quickly become one of the strongest armies in the world due to its high-tech armaments and its ability to manufacture a nuclear bomb within a few months (Fitzpatrick 2013). Moreover, following the territorial dispute with China and North Korea’s threats, Japan’s government seeks seriously to change the country’s pacifist constitution, which would change Japanese rank in strategic hedging index (SINA 2013). Before this is done, the economic capacity remains the cornerstone in supporting Japan’s competitive position vis à vis the other great powers (Fig. 7).

4.4.5 EU (Germany, France, and UK)

In the first half of the last century, Germany, UK, and France were among the top great powers in the world. After the Second World War, the US has formed a strategic alliance with Western European countries. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has become a cornerstone in ensuring US and European security. During the years of the Cold War, the transatlantic relations have been very close with instances of tension and temporary discord such as Suez Crisis in 1957, Vietnam War in the 1960s, and de Gaulle’s decision to pull France from NATO in 1966 (Gaddis 2005; Nielsen 2013). After the demise of the Soviet Union threat, EU countries lost several competitive advantages in the military sphere, and European military spending has decreased steeply. As a result US military spending was nearly twice that of the EU25’s by the early 2000s (SIPRI 2014). The decline in the European armies’ performance has clearly emerged during the Yugoslav Civil Wars; the conflict in Kosovo did not resolve until the military intervention of the US, which carried out most of the combat operations (Dinan 2004; Nielsen 2013). Following NATO’s military operation in Libya 2011, NATO Chief Anders Fogh Rasmussen mentioned “significant shortfalls in a range of European capabilities—from smart munitions, to air-to-air refueling, and intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance”, a statement suggesting that the European countries could not have succeeded without the US’ technical support (Nielsen 2012).

While economically the European Union is the largest economic bloc in the world, the accession of its members to an economic and political union has affected their sovereign decision-making capacity. For example, although some EU countries have appeared reluctant to ratchet up sanctions on Russia, broad economic sanctions have been extended until the end of January 2016. This decision could cost European firms around €5 billion in lost sales. More importantly, serious threat has emerged with the prospect of declining energy imports of oil and gas from Russia (Norman 2015).

Politically, the different EU countries’ positions of major international issues adversely affect the EU status as a politic and economic unified bloc. For instance, Britain’s Tony Blair stood in the US grace and supported the war on Iraq, while France’s Jacques Chirac and German Chancellor Gerhard Schroder opposed the war and joined the Russian position (Peterson 2004). Recently in November 2012, the vote on Palestine’s status in UN highlighted how deeply divided Europe is on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; 14 EU members voting in support of upgrading the Palestinian Authority’s observer status at the United Nations to ‘non-member state’ from ‘entity’, while another 12 were abstaining, and only 1 voted against the move (EurActiv 2012).

Arguably, most EU countries have entered into an unbalanced partnership with Washington, and have relied heavily on subsidies provided by the system leader, especially military aid, resulting in losing several competitive abilities. Moreover, belonging to a joint union and high levels of democracy affect their political and economic decision-making capabilities. Consequently, Germany, France, and UK occupy modest positions in the strategic hedging index, with substantial convergence in competitiveness (Figs. 8, 9, 10).

5 Conclusion

As highlighted above, strategic hedging is a form behavior used by states wanting to improve their competitiveness while at the same time avoiding direct confrontation with main contenders. It is an appealing option for states facing uncertainty due to structural changes in the international system such as the present unipolarity giving way to a process of power diffusion. Under such conditions strategic hedging becomes an attractive alternative for other strategies like balancing, bandwagoning, and buckpassing. Especially for second-tier states, it becomes a behavior of choice vis-à-vis the system leader. In this article we present a first attempt to measure the core components of a state’s strategic hedging capability and as such provide a comparative snapshot of those components by means of a composite index that facilitates comparison between second-tier states’ capabilities for strategic hedging. This index comprises three basic dimensions (economic capability, military power and decision-making capability), which are broken down into six sub-indicators: gross domestic product (GDP), foreign exchange and gold reserves, government debt, military expenditure, growth of military arsenal, and democracy. Because second-tier states in the international system are likely to have the greatest incentives to engage in strategic hedging, we apply the composite index to a sample of seven leading second-tier states in a comparative case study. The result is a ranking of the world’s major powers according to the strategic hedging capability they command. For the year 2013 China easily wins the strategic hedging race according to our index, with a score of 5.61 points that is about 3.33 points higher than Russia’s. Russia ranks second with 2.28 points; then come India, Japan, and Germany with 2.02, 1.98, 1.82 points, respectively. France and the United Kingdom run as close sixth and seventh with 1.57 and 1.40 points, respectively. These results indicate that for states to score high on strategic hedging capability, they need to score high for all core components of strategic hedging capability. Negligence of one of the components leads to a significant decline in total hedging capacity.

Because economic capability has a significant effect on the other basic dimensions of hedging (military power and decision-making capability), attention to the economic aspect must take priority by any state wishing to set up a successful hedging policy in the long term. For example, despite the rise of Russian military expenditure, the low volume of Russian GDP makes this military spending a negative factor from the viewpoint of ‘growth of military arsenal indicator’. Another example, the high level of government debt in Japan has led to decrease the willing to implement the sovereign financial decisions and to undermine the economic policymakers in Tokyo. However, the economic potential is a necessary condition but not a sufficient one for strategic hedging. The other components also play a key role in the success of hedging policy. For example, Japan and Germany have lost important points as a result of declining military expenditure. Also, high levels of democracy, and thus low decision-making capability, put European countries at modest positions in the strategic hedging index.

This index indicates strategic hedging capabilities, and thus signals potential engagement in this type of behavior for each individual country. As such it offers a road map of possible hedging behavior, which helps to understand key factors in successful hedging and in this way contributes to the advancement of the ‘strategic hedging’ concept. Of course, the question of measurement is only a part of the strategic hedging debate. A great deal of future research is needed to better understand how strategic hedging could change the unipolar system. However, this measure provides a novel means to capture and analyze an important aspect of international relations as it stimulates case studies, as well as both quantitative and qualitative analysis.

In what will hopefully be an annual endeavor, we will attempt to improve this index by building a larger data set, and increasing the number of countriesFootnote 8 included as priorities for future iterations. For example, new indicators to measure military power could be used such as global militarization index (GMI), the number of military personnel, and the level of military equipment. Moreover, the indicators could be given relative weighting in calculating the final index score, e.g. GDP indicator could have different weighting from the Government Debt indicator. Such endeavor could make design of the index more complex, but it would provide more precise details for measuring components of a state’s strategic hedging capability, and would help researchers to explore the year-on-year changes in the rankings of countries.

Notes

The seven leading second-tier states were selected on the basis of their relative economic and/or military weight (except the system leader; the United States).

The provocation could follow from a dramatic increase in the military arsenal and/or joining military alliances against the system leader.

There are other indicators to measure military power such as global militarization index (GMI), the number of military personnel, and the level of military equipment. However, due to the lack of accurate figures we only use a military spending index.

Exercise Malabar is an annual bilateral naval exercise between the United States and India (some years to include Japan, Australia and/or Singapore). The exercises take place every year since 1992 until 2014 (except for a brief interregnum, 3 years, after the 1998 Pokhran II nuclear tests) (Pandit 2014).

The Yoshida Doctrine is “a strategy adopted post World War II under Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, in which economics was to be concentrated upon majorly to reconstruct domestic economy while the security alliance with the US would be the guarantor of Japanese security” (Chansoria 2014).

See Defense of Japan (Annual White Paper), Available at: http://www.mod.go.jp/e/publ/w_paper/.

New emerging powers could be included, such as Brazil, South Korea, South Africa, and Turkey.

References

Aaronson, Susan Ariel. 2010. Is China killing the WTO? Chinese officials are ignoring both international and local law for companies that produce for export. The International Economy 24(1): 40–67.

Alterman, Jon. B. 2009. China’s soft power in the Middle East. In Chinese Soft Power and Its Implications for the United States, ed. McGiffert, Carola. Washington, D.C: Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS).

Anderlini, Jamil. 2009. China calls for new reserve currency. Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/7851925a-17a2-11de-8c9d-0000779fd2ac.html#axzz2bYy1gJNN. Accessed 24 March 2009.

Andersen, Robert. 2012. Support for democracy in cross-national perspective: the detrimental effect of economic inequality. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 30(4): 389–402.

Bandow, Doug. 2012. Strategic restraint in the near seas. Orbis 56(3): 486–502.

Benedictow, Andreas, Daniel Fjærtoft, and Ole Løfsnæs. 2013. Oil dependency of the Russian economy: an econometric analysis. Economic Modelling 32: 400–428.

Branigan, Tania. 2015. Support for China-led development bank grows despite US opposition. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/13/support-china-led-development-bank-grows-despite-us-opposition-australia-uk-new-zealand-asia. Accessed 15 March 2015.

Breslin, Shaun. 2013. China and the global order signalling threat or friendship. International Affairs 89(3): 615–634.

Chang, Hsin-Chen, Bwo-Nung Huang, and Chin Wei Yang. 2011. Military expenditure and economic growth across different groups: a dynamic panel Granger-causality approach. Economic Modelling 28(6): 2416–2423.

Chansoria, Monika. 2014. Relevance of the Yoshida Doctrine in current US–Japan ties. Japan Today. http://www.japantoday.com/category/opinions/view/relevance-of-the-yoshida-doctrine-in-current-u-s-japan-ties. Accessed 13 May 2014.

CIA. 2013a. The World Factbook. Field listing: Public debt, 2013. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2186.html.

CIA. 2013b. The World Factbook. Field listing: Reserves of foreign exchange and gold, 2013. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2188rank.html.

Cooper, Julian. 2013. The Russian economy twenty years after the end of the socialist economic system. Journal of Eurasian Studies 4(1): 55–64.

Democracy Ranking. 2014. http://democracyranking.org/wordpress/?page_id=14.

Dinan, Desmond. 2004. Europe Recast: A History of European Union. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Doyle, Michael W. 1983. Kant, liberal legacies, and foreign affairs. Philosophy & Public Affairs 12(3): 205–235.

Dreyer, June Teufel. 2007. China’s power and will: the PRC’s military strength and grand strategy. Orbis 51(4): 651–664.

EurActiv 2012. EU divided in UN vote on Palestine’s status. http://www.euractiv.com/global-europe/palestine-recognition-highlights-news-516369. Accessed 30 Nov 2012.

Evans, Michael. 2011. Power and paradox: Asian geopolitics and Sino-American relations in the 21st century. Orbis 55(1): 85–113.

Fitzpatrick, Michael. 2013. Inside Japan’s invisible army. Fortune. http://fortune.com/2013/08/05/inside-japans-invisible-army/. Accessed 5 August 2013.

Gaddis, John Lewis. 2005. The Cold War: A New History. London: Penguin Press.

Gao, Cheng. 2011. Market expansion and grand strategy of rising powers. The Chinese Journal of International Politics 4(4): 405–446.

Geeraerts, Gustaaf. 2011. China, the EU, and the new multipolarity. European Review 19(1): 57–67.

Gertz, Bill. 2013. Red tide: China deploys new class of strategic missile submarines next year. The Washington Post. http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/jul/23/china-deploy-new-strategic-missile-class-submarine/?page=all. Accessed 23 July 2013.

Glosny, Michael A. 2010. China and the BRICs: a real (but Limited) partnership in a unipolar world. Polity 42(1): 100–129.

Harrison, Mark. 1998. The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Horvath, Robert. 2011. Putin’s ‘Preventive Counter-Revolution’: Post-Soviet authoritarianism and the spectre of velvet revolution. Europe-Asia Studies 63(1): 1–25.

Huiyun, Feng. 2009. Is China a revisionist power. The Chinese Journal of International Politics 2(3): 313–334.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1958. Arms races: prerequisites and results. Public Policy 8: 41–86.

IMF. 2015. World Economic Outlook Database, April 2014 http://www.imf.org/external/data.htm.

Knutsen, Carl Henrik. 2011. Which democracies prosper? Electoral rules, form of government and economic growth. Electoral Studies 30(1): 83–90.

Layne, Christopher. 1993. The unipolar illusion: why new great powers will rise. International Security 17(4): 5–51.

Layne, Christopher. 2012. This time it’s real: the end of unipolarity and the Pax Americana. International Studies Quarterly 56(1): 203–213.

Li, Jie, Huaxia Huang, and Xiao Xiao. 2012. The sovereign property of foreign reserve investment in China: a CVaR approach. Economic Modelling 29(5): 1524–1536.

Lieber, Keir, and Gerard Alexander. 2005. Waiting for balancing: why the world is not pushing back. International Security 30(1): 109–139.

MCK. 2013. Government debt: how much is too much? The Economist. http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2013/01/government-debt. Accessed 2 January 2013.

Mankiw, N.Gregory, and Mark P. Taylor. 2006. Principles of Economics. Stamford: Thomson.

Monteiro, Nuno P. 2011. Unrest assured: why unipolarity is not peaceful. International Security 36(3): 9–40.

Newmyer, Jacqueline. 2009. Oil, arms, and influence: the indirect strategy behind Chinese military modernization. Orbis 53(2): 205–219.

Nielsen, Kristian L. 2013. Continued drift, but without the acrimony: US–European relations under Barack Obama. Journal of Transatlantic Studies 11(1): 83–108.

Nielsen, Nicolaj. 2012. NATO commander: EU could not do Libya without US. http://euobserver.com/defence/115650. Accessed 20 March 2012.

Norman, Laurence. 2015. EU extends economic sanctions on Russia until end of January. The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/eu-extends-economic-sanctions-on-russia-until-end-of-january-1434960823. Accessed 22 June 2015.

Nye, Joseph. 1990. The changing nature of world power. Political Science Quarterly 105(2): 177–192.

Nye, Joseph. 2004. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs.

OECD. 2008. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. Paris: OECD.

Okabe, Yoshikhiko. 2013. The Japanese Economy: a historical review and prospectus. Accounting and Finance 2: 134–136.

Pandey, Avaneesh. 2014. Japan’s economy shrinks in Q2 from higher sales tax effect, stokes deflation fears. International Business Time. http://www.ibtimes.com/japans-economy-shrinks-q2-higher-sales-tax-effect-stokes-deflation-fears-1656980. Accessed 13 August 2014.

Pandit, Rajat. 2014. India, US and Japan to kick off Malabar naval exercise tomorrow. The Times of India. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/India-US-and-Japan-to-kick-off-Malabar-naval-exercise-tomorrow/articleshow/38931444.cms. Accessed 23 July 2014.

Pape, Robert A. 2005. Soft balancing against the United States. International Security 30(1): 7–45.

Peterson, John. 2004. Europe, America, Iraq: worse ever, ever worsening? Journal of Common Market Studies 42(1): 9–26.

Rutland, Peter. 2008. Putin’s economic record is the oil boom sustainable? Europe-Asia Studies 60(6): 1051–1072.

Rywkin, Michael. 2012. Russian foreign policy at the outset of Putin’s third term. American Foreign Policy Interests 34(5): 232–237.

Sakwa, Richard. 2008. Putin’s leadership: character and consequences. Europe-Asia Studies 60(6): 879–897.

Salman, Mohammad, and Gustaaf Geeraerts. 2015. Strategic hedging and China’s economic policy in the middle east. China Report 51(2): 102–120.

Salman, Mohammad, Moritz Pieper, and Gustaaf Geeraerts. 2015. Hedging in the Middle East and China–US competition. Asian Politics & Policy 7(4): 575–596.

Schepelmann, Philipp, Yanne Goossens, and Arttu Makipaa. 2010. Towards Sustainable Development: Alternatives to GDP for Measuring Progress. Wuppertal: Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy.

Schweller, Randall L., and Pu Xiao. 2011. after unipolarity China’s visions of international order in an Era of US decline. International Security 36(1): 41–72.

SINA. 2013. Abe pushes for pacifist constitution revisement. http://english.sina.com/world/2013/0317/572405.html. Accessed 18 March 2013.

SIPRI. 2014 SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. http://www.sipri.org/research/armaments/milex/milex_database.

Tessman, Brock. 2012. System structure and state strategy: adding hedging to the menu. Security Studies 21(2): 192–231.

Tessman, Brock, and Wojtek Wolfe. 2011. Great powers and strategic hedging: the case of Chinese energy security strategy. International Studies Review 13(2): 214–240.

Wang, Jisi. 2005. China’s search for stability with America. Foreign Affairs 84(5): 39–48.

Wheeler, Graeme. 2004. Sound Practice in Government Debt Management. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Wolfe, Wojtek M. 2013. China’s strategic hedging. Orbis 57(2): 300–313.

Xinhua. 2013. China carries out land-based mid-course missile interception test. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-01/28/c_124285293.htm. Accessed 27 Jan. 2013.

Yongding, Yu. 2011. China can break free of the dollar trap. Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/2189faa2-bec6-11e0-a36b-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2bYy1gJNN. Accessed 4 August 2011.

Zakaria, Fareed. 1998. From Wealth to Power: The Unusual Origins of America’s World Role. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Zhang, Dewei, Yiqi Wang, Jingjing Wang, and Xu Weidong. 2013. Liquidity management of foreign exchange reserves in continuous time. Economic Modelling 31: 138–142.

Zuljan, Ralph. 2003. Allied and axis GDP. Articles on War. http://www.onwar.com/articles/0302.htm. Accessed 1 July 2003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geeraerts, G., Salman, M. Measuring Strategic Hedging Capability of Second-Tier States Under Unipolarity. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1, 60–80 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0010-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0010-6