Abstract

Thrash metal songs have confronted listeners with socio-political problems since the genre emerged in the 1980s. Its abrasive tone and dystopian language implicitly and explicitly attacks norms, religion, the economic and political status quo, and social injustice. In addition to these anthropocentric concerns lives a powerful critique of our problematic contemporary relationship with the more-than-human community. This paper examines implicit and explicit environmental ethical statements in 18 thrash songs released between 1987 and 2013 written by 12 bands. It shows a consistent ecologically dystopian position and critical ethical stance ripe for ecopedagogical and ethics education purposes. Following that, the article explores more specific environmental ethical issues and presents approaches to incorporating them into curricula with possible bridges to other musical genres. It concludes with a call for a deeper critical ethical conversation in the age of ecocide.

Similar content being viewed by others

“Human beings and the natural world are on a collision course.”

~ “World Scientists Warning to Humanity,” Union of Concerned Scientists, 1992

Thrash metal songs have confronted listeners with socio-political problems since the genre emerged in the 1980s. Its abrasive tone and dystopian language implicitly and explicitly attacks norms, religion, the economic and political status quo, and social injustice. In addition to these anthropocentric critiques lives a powerful critique of our problematic contemporary relationship with the more-than-human community. This paper examines implicit and explicit environmental ethical statements in 18 thrash songs released between 1987 and 2013 written by 12 bands. It shows a consistent ecologically dystopian position and critical ethical stance ripe for ecopedagogical and ethics education purposes. Following that, the article explores some of the more specific environmental ethical issues and presents approaches to incorporating them into curricula with possible bridges to other musical genres. It concludes with a call for a deeper critical ethical conversation in the age of ecocide.

In the 1980s, metal fractured into subgenres as it spread across the globe, thrash metal among them (Dunn et al. 2005). As a sub-genre, thrash expresses power through extremes in volume, tempo, technique, timbre, lyrics, dissonant harmony (usually expressed horizontally), and its associated art. Along with power metal, death metal and grindcore, it stands among the loudest, fastest, most dynamic, and most technically virtuosic offshoots of rock and roll. It is characterized by “fast percussive and low-register guitar riffs, overlaid with shredding-style lead work” (Galbraith 2011). Frequently, metal presents power as at best morally ambiguous and most often as abusive, harmful, or dystopian (Taylor 2009). Lyrics engage socio-political issues like civil repression, economic inequality and exploitation, environmental degradation, euthanasia, execution, nuclear warfare, political corruption, religious corruption, surveillance, uncontrolled technological innovation and war. Band names from across the world include Anthrax, Annihilator, Anvil, Artillery, Carnivore, Celtic Frost, Death Angel, Destruction, Exodus, Havok, Hirax, Kreator, Megadeth, Metal Church, Metallica, Nuclear Assault, Overkill, Powermad, Revocation, Savatage, Sepultura, Slayer, Sodom, Suicidal Tendencies, Testament. Voivod and Xentrix. The graphic art, font design, stage shows, dress, and sub-cultural mores thwart authority, glorify or avoid overt judgment of deviance and revel in destruction, dark activities or literal darkness (Weinstein 1991, p. 22–35). Power invigorates and endangers.

Social scientists, journalists, cultural critics, musicologists, music theorists, philosophers, and pedagogical theorists have examined metal. Deena Weinstein’s Heavy Metal: A Cultural Sociology (1991, revised 2000) examined metal culture’s sonic, visual, verbal and behavioral components. The sum total creates distinct if difficult-to-define codes and practices (2000, pp. 22–35). These codes and practices are seen as deviant and even dangerous by the dominant culture, a finding that resonates throughout the literature (Dunn et al. 2005, 2007; Snell and Hodgetts 2007, p. 444).

Metal fans and performers find meaning in deviance and alienation from the dominant culture. Brown (1995) examined secular and Christian thrash metal contexts and musical parameters, seeing thrash in particular as an aesthetic response to oppression. “Heavy metal and thrash is often used as a cathartic musical experience whereby youth transcend their frustrations with a social system on which they exert little or no control” (Brown 1995, p. 447). This transcendence can be observed in thrash’s extreme musical parameters–harmonic dissonance, rebellious and apocalyptic visions, and themes that oppose societal norms and embrace alienation (pp. 446–448). Rebellion spans cultures including adolescent American (Arnett 1991a, 1991b), Navajo (Deyhle 1998), Balinese youth (Baulch 2003), and Moroccan youth (Levine 2009). Alienation brings solidarity and “dis-alienating” culture that provides a philosophical framework and a cultural code for living (Bettez Halnon 2006, p. 46). Across these cultural contexts we find disaffected young people who find individual and collective catharsis, identity, and rituals of resistance and empowerment in a musically practiced subculture that emphasizes dystopia.

In Heavy Metal in Britain, Taylor looks at Black Sabbath’s, Judas Priest’s, Bolt Thrower’s, and Cathedral’s dystopian tendencies. She finds their critiques of the status quo to have

“the potential to resist completely anti-utopian pessimism in some of its darkest expressions, and when combined with lyrics that offer a critical position to the audience, identify contemporary mistakes, or overtly invoke elements of warning and hope, some metal songs become clearly dystopian rather than nihilistic” (2009, p. 105).

Other studies include Granholm’s (2012) discussion of ecological dystopia of the metalcore band Earth Crisis. Thrash metal art and culture create a milieu in which identities of discontent and resistance can be formed in a unified way and with a unified front.

Behind this culture lurk both aesthetics and ethics, both of which provide educational opportunities. In Metallica and Philosophy: A Crash Course in Brain Surgery (Irwin 2007), a number of authors connect Metallica’s lyrics to schools of philosophy and thereby philosophy educators with Metallica’s philosophical pedagogical value. Metallica’s songs about war incite our moral reasoning because they “exercise [our] imaginative empathy” (p. 14). Ahlkvist (1999) shows how sociology teachers can invite students to conduct cultural analyses (like those in the aforementioned literature) to explore important sociological issues, theories, and themes. The article provides evidence that his extensive use of metal in his sociology classes “facilitates a clear understanding of sociological ideas and their applicability to contemporary social issues” (p. 138). For our purposes, the social issues are environmental and we substitute sociological ideas with ecopedagogical ends.

Ecopedagogy is a term clarified by Richard Kahn in Critical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy, and Planetary Crisis. He explains:

[Ecopedagogy is] a movement concerned with the cosmological, technological, and organizational dimensions of social life, that seeks to achieve victory through its ability to:

-

1.

provide openings for the radicalization and proliferation of ecoliteracy programs both within schools and society;

-

2.

create liberatory opportunities for building alliances of praxis between scholars and the public (especially activists) on ecopedagogical interests; and

-

3.

foment critical dialogue and self-reflective solidarity across the multitude of groups that make up the educational left during an extraordinary time of extremely dangerous planetary crisis (Kahn, 2010, p. 56).

Importantly, ecological literacy develops knowledge, skills and ethics of and for the health of the interconnected web of economic, social and environmental life (see Creighton and Cortese 1992, p. 19; Orr 1992; Golley 1998, pp. 229–235; Reynolds 2010, p. 18). In all cases, people should translate their understanding of interconnected systems into moral positions that guide actions to sustain life. For Kahn (2010a), Greenwood (Gruenewald 2003a, 2003b) and Bowers (1993, 1994, 1997), ecological literacy ought to serve a particularly critical ethical perspective that pushes for liberation from western neoliberal, consumptive, antihuman and ecocidal hegemony. In the age of climate crisis, Kahn (2011, p. 10) urges people in higher education’s ecological literacy programs to

…pose a lot of problems for the powers that be; they should incite a lot of questioning and dissatisfaction; they should open up the old wounds that have been shot full of anaesthetic and demand that people learn to dwell in their collective fear, anger, grief, as well as everyday joys, to come to a deeper happiness than is now proffered by the cult of consumer expectations.

Thrash metal songs offer us this possibility if they are linked to relevant materials and deliberate reflection.

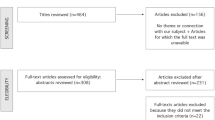

This paper now turns to 18 thrash songs about human and more-than-human environmental interactions written by 12 bands from 1987 to 2013 (Table 1). It shows environmental ethics literature-driven and emergent textual analytical results to explicate these songs’ lyrical themes regarding human-environmental interactions, showing the consistent dystopian position and critical ethical stance. Following that, the article explores some of the more specific environmental ethical issues and presents approaches to incorporating them into ethics curricula.

These 18 songs were deliberately sampled according to the following interlinked lyrical criteria. First, a thrash metal band wrote and performed the songs, an attribution derived from the bands’ inclusion on lists of thrash bands, through the bands’ musical and lyrical alignment with the characterization stated earlier, and from personal experience (Ranker 2015). Second, songs focused on an environmental subject. “Environment” in this context indicates that part of the natural world that is distinct from human culture, society, and economy including the biosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere and the atmosphere. The environment is not the built or political environment. While human beings are not genuinely separated from Earth’s systems this paper assumes a kind of separation for two reasons: a) the term environment has an “intuitive meaning for the average individual relating more clearly to what are known as ‘environmental issues’” (Clayton and Opotow 2003, p. 12) and b) the intuitive meaning is present in the songs and the ethical literature on which I rely. Topics include “earth,” “planet,” “biosphere,” “environment,” “biosphere,” “living things,” “air,” “water,” “seas,” “rain,” “forest,” “trees,” “the Amazon,” “precious land,” or “natural resources.” Third, humans are individual or collective agents in these songs. They are referred to as a race or species, as “we,” and as institutions like “corporations” or “the government.” Humans take actions that include blistering, burning, killing, polluting and raping. Fourth and finally, humans are characterized as having or lacking cognitive abilities by being “idiots” or “fools” or lacking ethical capacities each of which can be evaluated as good or bad.

Each song focuses on the damaging consequences of human interactions with the more-than-human environment. Topics include the pace or scope of climate change, chemical and solid waste pollution, extraction, unchecked corporate exploitation, industrial technological advances, hunting, and others. In all cases the songs embody “metal’s preoccupation with chaos, darkness and disaster, and…the genre’s rejection of utopianism,” as Taylor stated (2009, P. 90; see also Weinstein 1991, p. 39 and Harrell 1994, p. 39). Whether humans are described in the first person plural as “we” or in the third person as “human beings” or “mankind,” homo sapiens is culpable for all named environmental problems. Therefore, they present a host of “should” and “should not” statements that imply both theoretical and practical normative ethical frames for the environment. Normative ethical theories deal with kinds of things we might consider to be right or good (Jamieson 2008, p. 76). Practical ethics “views a narrow band of the same terrain in greater detail” (p. 76). In Practical Ethics, Singer states “ethics is not an ideal system that is noble in theory and no good in practice” (Singer 1993, p.2). I suggest, then, reading these songs as warnings about unsustainability and using them as problem-posing vehicles (see Kahn 2011) that can radicalize and sensitize listeners.

I propose the songs as ways to develop three capacities in ourselves and our students:

-

a.

The aesthetic experience of dystopian art coupled to outrage caused by human mistreatment of the environment.

-

b.

As ways to develop moral literacy by cultivating ethics sensitivity, ethical reasoning skills and moral imagination (Tuana 2007) with special attention to critical environmental ethics, human rights, and transgenerational justice.

-

c.

To develop ecological literacy (Orr 1992; Golley 1998) and sustainability meta-competencies especially systems thinking, temporal or anticipatory thinking, normative or ethical literacy (Wiek et al. 2011).

Following Orr (1992), we should be reflecting on the question, “What then?” repeatedly. To develop these capacities, two possible courses of action emerge, the first for faculty teaching music, metal studies, popular culture, or cultural studies and the second for those approaching from an environmental studies, environmental ethics, or sustainability studies vantage. These approaches are not mutually exclusive of one another, but they emphasize different aspects.

From my own teaching of metal as an art form and culture, I find that staying rooted in the big topics of resistance and dystopia are important. How are they manifest in these songs? Questions and explorations should turn on the vocal style, timbre and arrangement, tempo, rhythm, harmony and melody, and how song structures relate to lyrical content. Such an open exploration invites students and instructors to engage the full suite of songs with big unifying ideas. Starting from this large idea allows students to plumb the depths of individual songs where they will discover the connection between music and words. For example, those working in a musical theoretical space will learn the tonal language of these songs, uncovering thrash’s tendencies for minor, Phrygian, and Locrian modes and for half-step and tritonal vertical and horizontal relationships. In turn, they can discover how these tendencies relate to environmental abuses and dystopia. What, then, do these songs’ music and lyrics ask us about ourselves in relationship to the environment? This line of teaching is ecopedagogy through the back door.

The second ecopedagogical course of action focuses on human-environmental problems and uses the songs as a vehicle to reflect on a particular issue. For example, Megadeth’s “Countdown to Extinction” presents listeners with the ethical dilemma of trophy hunting for threatened or endangered species. Even more problematic, “the hunt is canned” so that whatever the hunted animal is, it has been caged so that it cannot escape and the human hunter can use a gun. As Dave Mustaine sings, “The battle’s unfair.” Mocking the so-called hunter, he sings “You’re so courageous.” The song finishes with a girl saying “One hour from now / Another species of life form / Will disappear off the face of the planet / Forever … and the rate is accelerating.” The dwindling numbers in the population and the lack of fairness and courage invites a discussion of the rights of entire species or populations, the rights of a single trapped animal and the virtue of individual hunters and global society.

A few ecopedagogical opportunities emerge from “Countdown to Extinction” modeled on philosophical thought experiments. That is, we can construct and reconstruct the song’s theoretical events to attend to moral and ethical problems, boundaries and gray areas, through ecopedagogical inquiry and reflection.

-

If the single caged animal were a silverback lowland gorilla, would it be owed special moral consideration? If it were a ubiquitous animal like a white tail deer in northeastern North America would it be owed moral standing? In either case, would the hunter be any more or less courageous?

-

What if the person shooting the animal is very poor, for example a poor man in Uganda who is forced into poaching gorillas? Unable to feed his family in a cash economy, should we afford him the latitude to cage and shoot a gorilla? Do his rights outweigh those of a gorilla?

-

What difference does the cage make? What difference does the gun make? What is a “fair fight?”

-

What is the moral difference between an endangered and caged animal shot point blank and a pig, cow or chicken, in a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO)? How do scale, technology, intent and species integrity independently and in combination change our moral evaluations?

-

What role does or should empathy or compassion play in our moral evaluations?

There is no shortage of materials on this topic at all. A thoughtful unit using this song as its entrée could investigate species extinction and hunting using the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005), the most recent IUCN Red List by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the publications of the Rainforest Action Network, or the Great Ape Project (2011). There is a very extensive literature on the ethics of non-human animals much too large to summarize here (see Singer 1975; Armstromg and Botzler 2003). The rights of other species is not the only issue to discuss.

Here I include other topics to consider, the songs from the list that fall under that category, and a very brief explanation.

-

Mothers, Personhood, and Value—Metallica, “Blackened”; Kreator, “When the Sun Burns Red”; Forbidden, “R.I.P.”; Nevermore, “Matricide”; Revocation, “Fracked”

These songs call the Earth “mother,” “Mother Earth” or “Mother Nature” implying that she should have the moral status of personhood and particularly motherhood.

-

Climate Change—Testament, “Greenhouse Effect”; Kreator, “When the Sun Burns Red”; Megadeth, “Dawn Patrol”

These songs address the effects of anthropogenic climate change in ways that open discussion for causes, impacts on people and the environment today, and our responsibilities to current and future generations of humans and the environment. Current trends in interdisciplinary writing around climate change make these songs especially salient (see Singer 2004; Garvey 2008; Oreskes and Conway 2010; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2014; Oreskes and Conway 2014).

-

Chemical Pollution—Kreator, “Toxic Trace”; Megadeth, “Set the World Afire”; Metallica, “Blackened”; Megadeth, “Dawn Patrol”; Sepultura, “Biotech is Godzilla”; Dirty Rotten Imbeciles, “Acid Rain”; Annihilator, “No Zone”; Revocation, “Tragedy of Modern Ages”; Revocation, “Age of Iniquity,” “Beloved Horrifier,” and “Fracked”

Each of these songs presents air, water, or radioactive contamination by humans. “Toxic Trace,” “Set the World Afire,” “Blackened,” and the four Revocation songs all deal with nuclear fallout which can easily connect to a much larger trope in metal on nuclear obliteration. This topic is itself so large that it could be dealt with separately.

-

Deforestation—Testament, “Greenhouse Effect”; Nuclear Assault, “Critical Mass”; Kreator, “When the Sun Burns Red”; Revocation, “Fracked”

These songs deal with deforestation as an ill in itself and one driven by other problems like fracking for oil and gas (see ProPublica 2015; Gold 2014) or climate change.

-

Greed and Markets—Nuclear Assault, “Critical Mass”; Xentrix, “No More Time”; Sepultura, “Biotech is Godzilla”; Revocation, “Tragedy of Modern Ages”

These songs explicitly link environmental degradation and unsustainability to humanity’s greed. They explicitly call out corporations and commodification as problems as problems for the commons.

The last set on greed and markets create bridging opportunities to broader interdisciplinary work. Kreator, Sepultura, and Xentrix all present issues related to corporate greed, something that would easily tie into broader critiques of growth economics, global capitalism, and produced crises (Kahn 2009) and the place of ecological militancy and resistance in education that seeks to resist the anti-democratic, ecocidal, and predatory tendencies of contemporary neo-liberal industrial culture (Giroux 2002, 2010; Kahn 2006; McLaren and Jaramillo 2007). Have ecocide and climate change changed everything? (Klein 2014). Those songs could, with some thought and careful curricular design, be used to frame discussion on the ecological impacts of economic globalization according to the “triple bottom line” of sustainability; i.e. the effects to society/culture, economy, and the other-than-human environment. In other readings, we might consider what the philosopher Herbert Marcuse called “the Great Refusal,” “a political practice of methodological disengagement from and refusal of the Establishment, aiming at a radical transvaluation of values” (Marcuse 1964, p. 6). Perhaps the “stand” that Testament calls for in “Greenhouse Effect” is in fact a renunciation of ecocidal culture as possible.

The potential theoretical and practical ethical questions raised by the previous discussion shows their ecopedagogical worth. First, they attend to different dimensions of social life and their ethical ramifications. Second, they provide openings for radicalization by critically examining the causes and consequences of ecological crises. Third, liberatory opportunities emerge through direct experience, self-or community self-reflection, and/or educational praxis (the merger of educational theory and practice) with and from these songs’ messages.

Before concluding, the ethics curricula proposed here are only a beginning. Much as Irwin (2007) suggests, metal excites the moral imagination. Other genres deal with other issues from a critical stance. As noted above, there is already a bridge between critical environmental ethics and anti-capitalist stances in thrash metal. Another metal subgenre could be included here too, grindcore which is arguably more anti-establishment in its ethical positions, lurid and dystopian in its lyrics and art, and musically extreme. Bands such as Cattle Decapitation, Agorophobic Nosebleed, and Napalm Death are noted for their relentless criticism of globalization, exploitation of humans and animals, and similar topics. But other environmental ethical stances such as reverence could be explored in Scandinavian black metal. Finally, folk music has a long tradition of addressing environmental and economic ethics, making a conversation between these musical genres ripe for deep and reflective ecopedagogy.

This article calls for radical interdisciplinarity toward ecological literacy, sustainability, and just processes. According to Paulo Freire (1973, pp. 12–13), a “radical” sees contradictions in society and culture that are rooted in history and who are called to raise people’s consciousness and co-participate to transform those contradictions. By interdisciplinarity I mean conversation and collaboration between practitioners of different academic, artistic, and practical disciplines. The ethical dimensions raised in the songs highlighted here can and should develop a polylogue between scientists, engineers, musicians, politicos, philosophers, teachers, activists, and citizens for the purposes of developing a radical critical consciousness about people’s interaction with the Earth. In the age of unfolding and accelerating climate disruption and the sixth extinction, we owe it to ourselves, our students, and to all citizens to critically engage the sustainability and unsustainability of modern life. Through that engagement, we might not lose all, steer away from the collision course, and find hope on earth (Ehrlich and Tobias 2014).

References

Ahlkvist, J. 1999. Music and cultural analysis in the classroom: Introducing sociology through heavy metal. Teaching Sociology 27(2): 126–144.

Armstromg, S.J., and R.G. Botzler. 2003. The animal ethics reader. New York: Routledge Press.

Arnett, J. 1991a. Adolescents and heavy metal music: From the mouths of metalheads. Youth and Society 23(1): 76–98.

Arnett, J. 1991b. Heavy metal music and reckless behavior among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 20(6): 573–592.

Baulch, E. 2003. Gesturing elsewhere: The identity politics of the Balinese death/thrash metal scene. Popular Music 22(2): 195–215.

Bettez Halnon, K. 2006. Heavy metal carnival and dis-alienation: The politics of grotesque realism.

Brown, C. 1995. Musical responses to oppression and alienation: blues, spirituals, secular thrash, and Christian thrash metal music. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 8(3): 439–452.

Clayton, S.D., and S. Opotow. 2003. Introduction: Identity and the natural environment. In Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature, ed. S.D. Clayton and S. Opotow, 1–24. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Creighton, S.H., and A.D. Cortese. 1992. Environmental literacy and action at Tufts University. New Directions for Higher Education 77(2): 19–30.

Deyhle, Donna. 1998. From break dancing to heavy metal: Navajo youth, resistance, and identity. Youth and Society 30(1): 3–3.

Dunn, S., S. McFadyen, S. Dunn, S. McFayden, and S. Feldman. 2005. Metal: A Headbanger’s journey. Burbank: Seville Pictures and Warner Home Video.

Dunn, S., S. McFadyen, S. Dunn, S. McFayden, and S. Feldman. 2007. Global metal. Burbank: Seville Pictures and Warner Home Video.

Ehrlich, P., and C.T. Tobias. 2014. Hope on earth: A conversation. London: University of Chicago Press.

Freire, P. 1973. Educating for critical consciousness. New York: Continuum.

Galbraith, P. 2011. Thrash metal. Accessed from http://mapofmetal.com/#/home.

Garvey, J. 2008. The ethics of climate change: Right and wrong in a warming world. London: Continuum Press.

Giroux, H. 2002. Neoliberalism, corporate culture, and the promise of higher ducation: The University as a public democratic sphere. Harvard Educational Review 72(4): 425–463.

Giroux, H. 2010. Bare pedagogy and the scourge of neoliberalism: Rethinking higher education as a democratic public sphere. The Educational Forum 74(3): 184–196.

Gold, R. 2014. The boom: How fracking ignited the american energy revolution and changed the world. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Golley, F. 1998. A primer for environmental literacy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Granholm, K. 2012. Metal, the end of the world, and radical environmentalism: Ecological apocalypse in the lyrics of earth crisis. In Anthems of apocalypse: Popular music and apocalyptic thought, ed. C. Partridge. Sheffield: Phoenix Press.

Great Ape Project. 2011. World declaration on great primates. Accessed from http://www.greatapeproject.org/en-US/oprojetogap/Declaracao/declaracao-mundial-dos-grandes-primatas.

Gruenewald, D.A. 2003a. The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher 32(4): 3–12. doi:10.3102/0013189X032004003.

Gruenewald, D. 2003b. Foundations of place: A multidisciplinary framework for placeconscious education. American Education Research Journal 40: 619–654. doi:10.3102/00028312040003619.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014. Climate change 2014 synthesis report: Summary for policymakers. Accessed from http://ipcc.ch/pdf/assessmentreport/ar5/syr/AR5_SYR_FINAL_SPM.pdf.

Irwin, W. 2007. Metallica, emotion, and morality. In Metallica and philosophy: A crash course in brain surgery, ed. Irwin William, 5–15. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Jamieson, D. 2008. Ethics and the environment. London: Cambridge University Press.

Kahn, R. 2006. The educative potential of ecological militancy in an age of big oil: Towards a marcusean ecopedagogy. Policy Futures in Education 4(1): 31–44.

Kahn, R. 2009. Producing crisis: Green consumerism as an ecopedagogical issue. In Critical pedagogies of consumption, ed. Jenny Sandlin and Peter McLaren. New York: Routledge.

Kahn, R. 2010. Critical pedagogy, ecoliteracy, and planetary crisis: The ecopedagogy movement. New York: Peter Lang.

Kahn, R. 2011. How should global climate change Change the climate of our conversation in education? Norway: Speech delivered in Oslo.

Klein, N. 2014. This changes everything: Capitalism versus the climate. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Levine, M. 2009. Doing the devil’s work: Heavy metal and the threat to public order in the muslim world. Social Compass 56(4): 564–576.

Marcuse, H. 1964. One-dimensional man: Studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

McLaren, P., and N. Jaramillo. 2007. Pedagogy and praxis in the age of empire: Towards a new humanism. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Oreskes, N., and E. Conway. 2010. Merchants of doubt. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Oreskes, N., and E. Conway. 2014. The collapse of western civilization: A view from the future. New York: Columbia University Press.

Orr, D.W. 1992. Ecological literacy: Education and the transition to a postmodern world. Albany: State University of New York Press.

ProPublica. 2015. Fracking: Gas Drilling’s Environmental Threat. Accessed from http://www.propublica.org/series/fracking.

Ranker. 2015. New Waves of Thrash Metal Bands. Accessed from http://www.ranker.com/list/new-wave-of-thrash-metal-bands-v1/petr_erm_k?&var=5.

Reynolds, H.L. 2010. Core learning goals for campus-wide environmental literacy: Overview. In Teaching environmental literacy: Across campus and across the curriculum, ed. H.L. Reynolds, E.S. Brondizio, J.M. Robinson, D. Karpa, and B.L. Gross, 17–28. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Singer, P. 1975. Animal liberation: A new ethics for our treatment of animals. New York: Random House.

Singer, P. 1993. Practical Ethics. New York and London: Cambridge University Press.

Singer, P. 2004. One World, 2nd ed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Snell, D., and D. Hodgetts. 2007. Heavy metal, identity and the social negotiation of a community of practice. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 17: 430–445.

Taylor, L.W. 2009. Images of human-wrought despair and destruction: Social critique in British apocalyptic and dystopian metal. In Heavy metal music in Britain, ed. G. Bayer, 89–110. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

Tuana, N. 2007. Conceptualizing moral literacy. Journal of Educational Administration 45(4): 364–378. doi:10.1108/09578230710762409.

Wiek, A., L. Withycombe, and C.L. Redman. 2011. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science 6: 203–218. doi:10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6.

Weinstein, D. 1991. Heavy metal: A cultural sociology. New York: Lexington Books.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buckland, P.D. When all is lost: thrash metal, dystopia, and ecopedagogy. International Journal of Ethics Education 1, 145–154 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-016-0013-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-016-0013-z